Project: Search and Sample Return

The NASA/Udacity search and sample return challenge consists of controlling a rover in Unity simulation to autonomously map an unknown terrain and locate "samples" of interest scattered throughout.

The simulation environment can be found here: https://github.com/udacity/RoboND-Rover-Unity-Simulator

The simulation calls drive_rover.py, which instantiates a rover class containing requisite parameters for system function, and calls perception_step.py() and decision_step.py() once each loop to handle Rover perception and AI respectively.

Parameters: I used the fastest graphics quality and 640 x 480 resolution

Perception Step

To begin with, perception_step() converts the camera image obtained this time step at Rover.img to rover coordinates using the transformation matrix specified by the openCV getPerspectiveTransform() function, following the suggestions of the instructors.

After the image transformation, the warped image is passed to color_thresh() for color thresholding for basic computer vision.

I took the advice of the initial page and decided to do my color thresholding in HSV to more easily differentiate between the three states of interest (obstacles, path, and samples). Basic code flow for color thresholding function is as follows: - convert input image to HSV - generate binary image from HSV ranges relating to navigatable path - generate binary image from HSV ranges relating to samples/rocks - define the obstacles as the NOT of the combined sample and path binaries - return binary arrays for each of the above steps for further coordinate transformation and navigational planning

After the color thresholding returned the binaries, I wanted to use them to perform any additional perception/computer vision steps required, so as to prevent passing or storing numpy arrays in the Rover class.

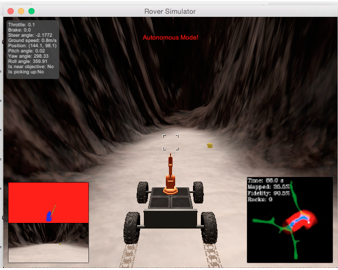

Once I have the thresholded images, I can update the rover perception output image on the lower lefthand side of the screen using the commands:

Rover.vision_image[:,:,0] = np.zeros_like(Rover.img[:,:,0]) + threshold_images[1]*255

Rover.vision_image[:,:,1] = np.zeros_like(Rover.img[:,:,0]) + threshold_images[2]*255

Rover.vision_image[:,:,2] = np.zeros_like(Rover.img[:,:,0]) + threshold_images[0]*255

This creates a real time grid on the lower right hand side, where obstacles appear as red, the path appears as blue, and theres a green line pointing towards any observed rock samples

From these global binaries, I use three parameters to pass to the Rover decision_step():

-

the number of entires in the navigatable path binary.

len(path_y)

This tells me how many navigatable pixels are being picked up by the camera image, which I use to detect when a wall is approaching

-

the median y value of the observed navigatable path within a range Rover.x_range:

path_y[path_x < Rover.x_range]

This allows me to compute the desired y value in rover coordinates to pass to decision_step(). In order to minimize noise, i pass the computed median y pixel value to a numpy array containing the past 10 measurements, and average the values. The averaged value is what is then passed to the rover class for use in decision_step()

-

an offset factor from the median y value so the Rover will slightly favor one side of the path to the other:

Rover.offset_factor * np.median(naviagateable_section_of_interest[naviagateable_section_of_interest > 0]

The offset factor is the median value of all y pixels on the right side of the rover coordinate system, I used this metric so it would scale with path size. Also its multiplied by Rover.offset_factor, which is ~= .4, so the rover is closer to the true median.

After computing the above parameters, I convert the rover coordinate images to global x,y using the rover class Rover.pos and Rover.yaw parameters. Once in global coordinates, i can update the map on the right hand side of the screen using the commands:

# Update Rover worldmap (to be displayed on right side of screen)

Rover.worldmap[obstacle_y_world, obstacle_x_world, 0] += 1

Rover.worldmap[rock_y_world, rock_x_world, 1] += 1

Rover.worldmap[path_y_world, path_x_world, 2] += 1

Decision step

Since perception_step() does most of the heavy lifting with the numpy calculations, decision_step() is relatively simple.

On initialisation, the rover sets its orientation to the starting position

after completion, decision_step() uses essentially the same flow as the sample implementation and is broken into three parts:

- check the number of navigatable pixels computed by the perception step

if (Rover.navigateable_path_pixels < Rover.go_forward):

- If the number of navigateable pixels is above the required threshold for forward motion, set the steering angle to be the crosscheck error of the rovers y position from the offset value multiplied by a proportional gain:

Rover.error = Rover.offset-Rover.des_y_pos

steer = - Rover.tau_p * Rover.error

Rover.steer = np.clip( (steer * 180/np.pi) , -15, 15)

- else if the number of navigatable pixels is below the required threshold for forward motion, stop the rover and initiate turning

until the rover sees enough pixels to go forward again

if Rover.vel > 0.2:

Rover.throttle = 0

Rover.brake = Rover.brake_set

Rover.steer = 0

# If we're not moving (vel < 0.2) then do something else

elif Rover.vel <= 0.2:

# Now we're stopped and we have vision data to see if there's a path forward

if (Rover.navigateable_path_pixels < Rover.go_forward):

Rover.throttle = 0

Rover.brake = 0

Rover.steer = 15

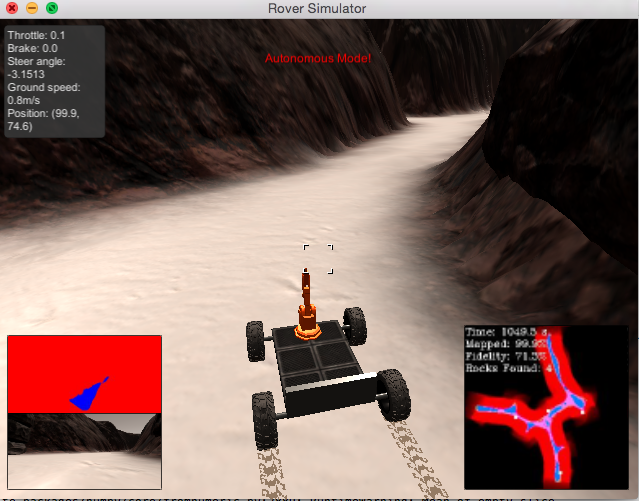

Overall, the implementation works relatively well as a lightweight mapping tool, able to map close to 100% with a fidelity in the range of 70-80%, usually spotting 4-6 samples.

But in general, it suffered from imperfections and could be improved in a number of ways.

First off, the fiedlity could be improved with a better specification of the HSV ranges for the navigateable path. I'm sure there is an ideal cutoff point, and I'm pretty sure I didnt nail it entirely. Similarly, the rover sometimes had trouble detecting samples (sometimes as low as 4 samples detected with 99.8% mapped) which is probably related to an incomplete HSV specification for sample color. This could be improved by inspecting more camera images with rocks and updating the HSV ranges accordingly.

decision_step() generally keeps the thrusters at a low rate to prevent roll and pitch angles messing with the coordinate transformation, and allowing the rover to minimize the holonomic constraints of the differential drive kinematics by moving and turning very slowly. This led to an overall mapping time > 1000s, which is probably larger than neccessary. Adjustment of the thruster, max velocity, and stopping threshold could let the rover complete in a faster time frame without sacraficing too much fidelity losses.

Also, the offset factor as the desired position was a pretty crude tool for implementing a wall crawler. Even though it worked relatively well in this map, if such a thing was to be implemented it should be related to a value that drops more quickly to 0 in small paths or near obstacles, that way the rover could react more efficiently to oncoming changes in environment. Regardless, I'm sure there are better ways to get the rover on one side of the path.

In terms of code, the perception step should have taken more precaution when using numpy on arrays. Generally, calculations should always be preceded by some sort of len() or isnan() check to make sure that the output is defined. My perception_step() lacked these checks on a couple numpy calcs and as a result I occaisonally got

RuntimeWarning: Mean of empty slice. out=out, **kwargs)

or

python3.5/site-packages/numpy/core/_methods.py:80: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in double_scalars ret = ret.dtype.type(ret / rcount)

which can cause some ugly undefined behaviors

I do not have a coding background as well, so I'm never entirely sure where to make runtime concessions to alleviate stack strain, so I'm sure a seasoned coder looking at my function calls in perception_step() would cringe to see where I do and do not let things go out of scope, where I assign something to a local variable that could have been inlined, or where I make copies instead of pass by reference, or pile variables on the stack unneccesarily.

If I had more time, I would have liked to implement a better method for calculating desired trajectories, such as A* with smoothing defined in a small window in front of the rover. That way I could have obstacle avoidance in my trajectory planning and could have gotten myself out of trouble more easily. It also would have made picking up samples easier to implement since I could just change my desired location passed to A* as the location of the sample. My biggest problem implementing picking up samples was specifying a trajectory to the sample that wouldn't get the rover stuck either there or on its way back, and A* could have solved this for sure. Also, a return_home() function would be simple to write. The biggest tradeoff would be computational complexity having to generate a heuristic and expand the array, but I'm sure there exists a small enough window where complexity is reasonably small and the calulated trajectory is still useful.

Also I wasn't quite sure if we could assume the rover had knowledge of the map before hand, or if it needed to use the map generated by perception_step() to calculate desired states. I erred on the side of caution and used the generated map to calulate desired rover states, but it might have been cool to use dynamic programming on the true map beforehand and write some sort of hash function relating current system state to desired trajectory and just have the perception_step() focus on mapping the path.

And if I had all the time in the world I would have liked to use the fact that the rover had four steerable wheels capable of rotating in either diection to program kinematics without holonomic constraints. Then I would essentially never get stuck and A* wouldnt even need smoothing (although some smoothing probably never hurts for minimizing jerk)

Also as a note, I wasn't aware of the updated roversim 2 until I had my submission returned to me. As a result, I did all of my programming on the original Roversim. After running my code on Roversim2, it appears theres some problem counting the rock samples observed, even though they appear on the map on the bottom right when detected (and as a green line in the rover image on the bottom left).