SneakySnake:snake:: A Fast and Accurate Universal Genome Pre-Alignment Filter for CPUs, GPUs, and FPGAs

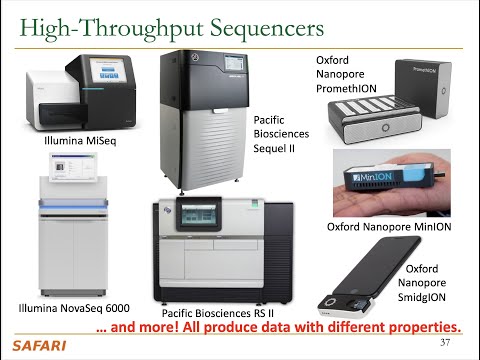

The first and the only pre-alignment filtering algorithm that works efficiently and fast on modern CPU, FPGA, and GPU architectures. SneakySnake greatly (by more than two orders of magnitude) expedites sequence alignment calculation for both short (Illumina) and long (ONT and PacBio) reads. Described by Alser et al. (preliminary version at https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.09020).

💡SneakySnake now supports multithreading and pre-alignment filtering for both short (Illumina) and long (ONT and PacBio) reads

💡Watch our lecture about SneakySnake!

git clone https://github.com/CMU-SAFARI/SneakySnake

cd SneakySnake/SneakySnake && make

#./main [DebugMode] [KmerSize] [ReadLength] [IterationNo] [ReadRefFile] [# of reads] [# of threads] [EditThreshold]

# Short sequences

./main 0 100 100 100 ../Datasets/ERR240727_1_E2_30000Pairs.txt 30000 10 10

# Long sequences

./main 0 20500 100000 20500 ../Datasets/LongSequences_100K_PBSIM_10Pairs.txt 10 40 20000- Getting Started

- Key Idea

- Benefits of SneakySnake

- Using SneakySnake

- Directory Structure

- Getting help

- Citing SneakySnake

- Limitations

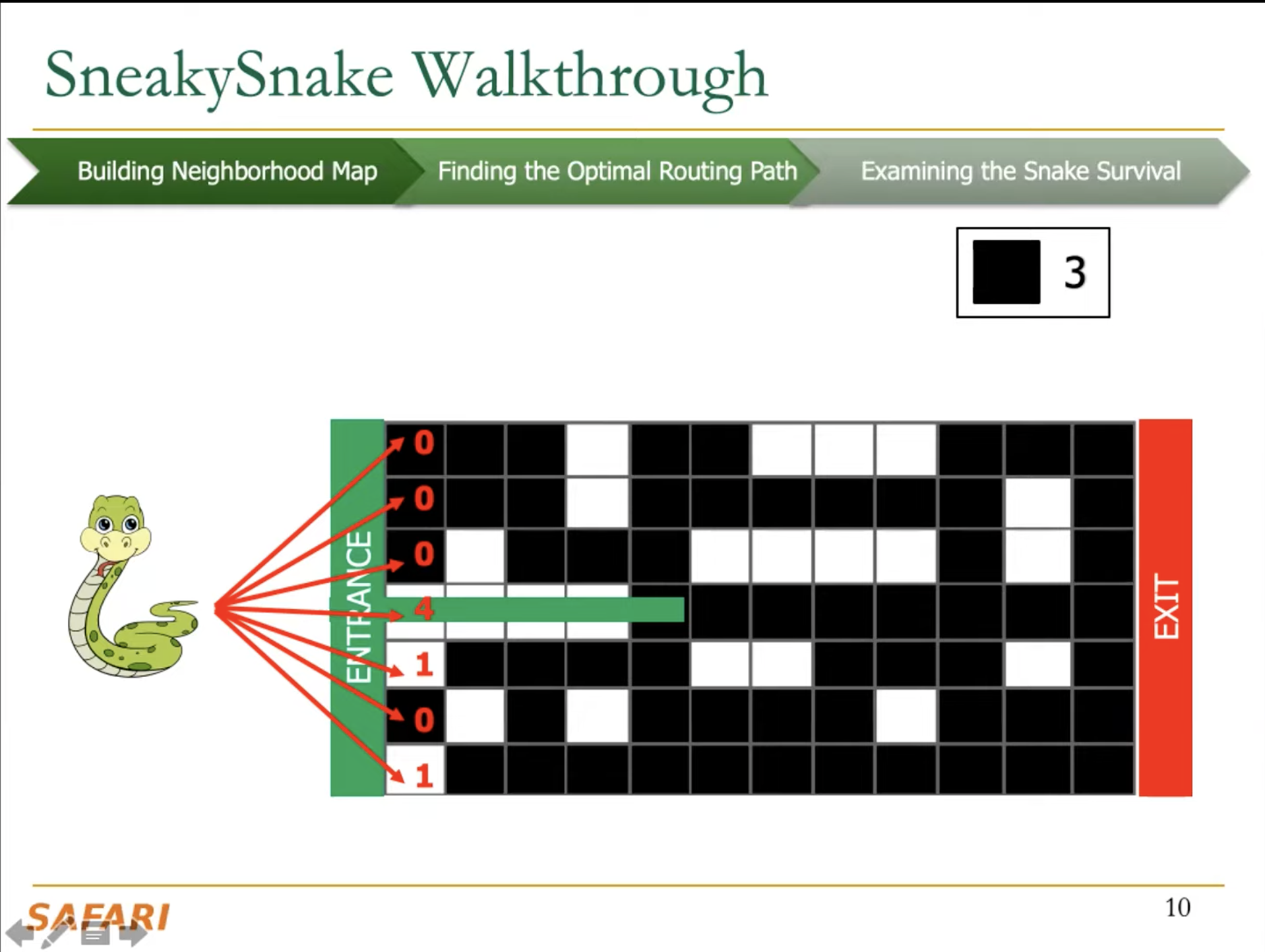

The key idea of SneakySnake is to reduce the approximate string matching (ASM) problem to the single net routing (SNR) problem in VLSI chip layout. In the SNR problem, we are interested in only finding the optimal path that connects two terminals with the least routing cost on a special grid layout that contains obstacles. The SneakySnake algorithm quickly solves the SNR problem and uses the found optimal path to decide whether performing sequence alignment is necessary. Reducing the ASM problem into SNR also makes SneakySnake efficient to implement for modern high-performance computing architectures (CPUs, GPUs, and FPGAs).

SneakySnake significantly improves the accuracy of pre-alignment filtering by up to four orders of magnitude compared to the state-of-the-art pre-alignment filters, Shouji, GateKeeper, and SHD. Using short sequences, SneakySnake accelerates Edlib (state-of-the-art implementation of Myers’s bit-vector algorithm) and Parasail (sequence aligner with configurable scoring function), by up to 37.7× and 43.9× (>12× on average), respectively, without requiring hardware acceleration, and by up to 413× and 689× (>400× on average), respectively, using hardware acceleration. Using long sequences, SneakySnake accelerates Parasail by up to 979× (140.1× on average). SneakySnake also accelerates the sequence alignment of minimap2, a state-of-the-art read mapper, by up to 6.83× (4.67× on average) and 64.1× (17.1× on average) using short and long sequences, respectively, and without requiring hardware acceleration. As SneakySnake does not replace sequence alignment, users can still configure the aligner of their choice for different scoring functions, surpassing most existing efforts that aim to accelerate sequence alignment.

SneakySnake is already implemented and designed to be used for CPUs, FPGAs, and GPUs. Integrating one of these versions of SneakySnake with existing read mappers or sequence aligners requires performing three key steps: 1) preparing the input data for SneakySnake, 2) overlapping the computation time of our hardware accelerator with the data transfer time or with the computation time of the to-be-accelerated read mapper/sequence aligner, and 3) interpreting the output result of our hardware accelerator.

- All three versions of SneakySnake require at least two inputs: a pair of genomic sequences and an edit distance threshold. Other input parameters are the values of t and y, where t is the width of the chip maze of each subproblem and y is the number of iterations performed to solve each subproblem. Sneaky-on-Chip and Snake-on-GPU use a 2-bit encoded representation of bases packed in uint32 words. This requirement is not unique to Sneaky-on-Chip and Snake-on-GPU. Minimap2 and most hardware accelerators use a similar representation and hence this step can be opted out from the complete pipeline. If this is not the case, we already provide the script to prepare such a compact representation in our implementation. For Snake-on-Chip, it is provided in lines 187 to 193 in https://github.com/CMU-SAFARI/SneakySnake/blob/master/Snake-on-Chip/Snake-on-Chip_test.cpp and for Snake-on-GPU, it is provided in lines 650 to 710 in https://github.com/CMU-SAFARI/SneakySnake/blob/master/Snake-on-GPU/Snake-on-GPU.cu. We also observe that widely adopting efficient formats such as UCSC’s .2bit (https://genome.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/help/twoBit.html) format (instead of FASTA and FASTQ) can maximize the benefits of using hardware accelerators and reducing the resources needed to process the genomic data.

- The second step is left to the developer. If the developer is integrating, for example, Snake-on-Chip with an FPGA-based read mapper, then a single SneakySnake filtering unit of Snake-on-Chip (or more) can be directly integrated on the same FPGA chip, given that the FPGA resource usage of a single filtering unit is very insignificant (<1.5%). This can eliminate the need for overlapping the computation time with the data transfer time. The same thing applies when the developer integrates Snake-on-GPU with a GPU-based read mapper. The developer needs to evaluate whether utilizing the entire FPGA chip for only Snake-on-Chip (achieving more filtering) is more beneficial than combining Snake-on-Chip with an FPGA-based read mapper on the same FPGA chip.

- For the third step, both Sneaky-on-Chip and Snake-on-GPU return back to the developer an array that contains the filtering result (whether a sequence pair is similar or dissimilar) that appear in the same order of their original sequence pairs (input data to the first step). An array element with a value of 1 indicates that the pair of sequences at the corresponding index of the input data are similar and hence a sequence alignment is necessary.

SneakySnake-master

├───1. Datasets

└───2. Snake-on-Chip

└───3. Hardware_Accelerator

├───4. Snake-on-GPU

├───5. SneakySnake-HLS-HBM

├───6. SneakySnake

├───7. Evaluation Results

- In the "Datasets" directory, you will find six sample datasets that you can start with. You will also find details on how to obtain the datasets that we used in our evaluation, so that you can reproduce the exact same experimental results.

- In the "Snake-on-Chip" directory, you will find the verilog design files and the host application that are needed to run SneakySnake on an FPGA board. You will find the details on how to synthesize the design and program the FPGA chip in README.md.

- In the "Hardware_Accelerator" directory, you will find the Vivado project that is needed for the Snake-on-Chip.

- In the "Snake-on-GPU" directory, you will find the source code of the GPU implementation of SneakySnake. Follow the instructions provided in the README.md inside the directory to compile and execute the program. We also provide an example of how the output of Snake-on-GPU looks like.

- In the "SneakySnake-HLS-HBM" directory, you will find the source code of the FPGA-HBM implementation of the SneakySnake algorithm (https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.06433). Follow the instructions provided in the README.md inside the directory to compile and execute the program.

- In the "SneakySnake" directory, you will find the source code of the CPU implementation of the SneakySnake algorithm. Follow the instructions provided in the README.md inside the directory to compile and execute the program. We also provide an example of how the output of SneakySnake looks like using both verbose mode and silent mode.

- In the "Evaluation Results" directory, you will find the exact value of all evaluation results presented in the paper and many more.

If you have any suggestion for improvement, please contact mohammed dot alser at inf dot ethz dot ch If you encounter bugs or have further questions or requests, you can raise an issue at the issue page.

If you use SneakySnake in your work, please cite:

Mohammed Alser, Taha Shahroodi, Juan Gomez-Luna, Can Alkan, and Onur Mutlu. "SneakySnake: A Fast and Accurate Universal Genome Pre-Alignment Filter for CPUs, GPUs, and FPGAs." Bioinformatics (2020). link, link

Gagandeep Singh, Mohammed Alser, Damla Senol Cali, Dionysios Diamantopoulos, Juan Gómez-Luna, Henk Corporaal, Onur Mutlu. "FPGA-Based Near-Memory Acceleration of Modern Data-Intensive Applications." IEEE Micro (2021). link, link

Below is bibtex format for citation.

@article{10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1015,

author = {Alser, Mohammed and Shahroodi, Taha and Gómez-Luna, Juan and Alkan, Can and Mutlu, Onur},

title = "{SneakySnake: a fast and accurate universal genome pre-alignment filter for CPUs, GPUs and FPGAs}",

journal = {Bioinformatics},

year = {2020},

month = {12},

abstract = "{We introduce SneakySnake, a highly parallel and highly accurate pre-alignment filter that remarkably reduces the need for computationally costly sequence alignment. The key idea of SneakySnake is to reduce the approximate string matching (ASM) problem to the single net routing (SNR) problem in VLSI chip layout. In the SNR problem, we are interested in finding the optimal path that connects two terminals with the least routing cost on a special grid layout that contains obstacles. The SneakySnake algorithm quickly solves the SNR problem and uses the found optimal path to decide whether or not performing sequence alignment is necessary. Reducing the ASM problem into SNR also makes SneakySnake efficient to implement on CPUs, GPUs and FPGAs.SneakySnake significantly improves the accuracy of pre-alignment filtering by up to four orders of magnitude compared to the state-of-the-art pre-alignment filters, Shouji, GateKeeper and SHD. For short sequences, SneakySnake accelerates Edlib (state-of-the-art implementation of Myers’s bit-vector algorithm) and Parasail (state-of-the-art sequence aligner with a configurable scoring function), by up to 37.7× and 43.9× (\\>12× on average), respectively, with its CPU implementation, and by up to 413× and 689× (\\>400× on average), respectively, with FPGA and GPU acceleration. For long sequences, the CPU implementation of SneakySnake accelerates Parasail and KSW2 (sequence aligner of minimap2) by up to 979× (276.9× on average) and 91.7× (31.7× on average), respectively. As SneakySnake does not replace sequence alignment, users can still obtain all capabilities (e.g. configurable scoring functions) of the aligner of their choice, unlike existing acceleration efforts that sacrifice some aligner capabilities.https://github.com/CMU-SAFARI/SneakySnake.Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.}",

issn = {1367-4803},

doi = {10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1015},

url = {https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1015},

note = {btaa1015},

eprint = {https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/advance-article-pdf/doi/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1015/35152174/btaa1015.pdf},

}- SneakySnake may calculate an approximated edit distance value that is very close to the actual edit distance. However, it does not over-estimate the edit distance value (i.e., its calculated edit distance is always slightly less than or equal the actual edit distance).