A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias. ― Oscar Wilde

Science is collaborative and cooperative (even though also competitive) and money is the best tool to bring people together. So, for the purpose of creating an ecosystem to speed up biodiversity based biotechnology to foster a bioeconomy, it makes a lot of sense to create a complementary currency. Genecoin is the complementary cryptocurrency that will allow scientists, entrepreneurs, financiers, philanthropist, service providers, labs, researchers together, to interact in a fast, safe and cheap way to make this change happen and promote bioeconomy. Genecoin operates in the Ethereum blockchain and it is available at the Proof exchange. It starts now and it will live in the blockchain forever.

For most of human history, scientists were isolated people, working with limited resources, either from their own families or donated by mecenas. It was over the last almost 2 centuries that science started to 'institutionalize': scientists were gathering in research institutes and universities around the world, that were financed by governments and industry (De Meis, 2008). In the XVII century, the estimated number of scientists in the world was 150 and there is no estimation of the amount of knowledge (in number of scientific articles published) they produced (De Meis, 2008).

even though we know that in 1800, the best library in the world was at the University of Oxford and it had, in its 'natural philosophy section', the closest to what we call 'science' today, about 800 volumes, that did not represent the production of that year, but all the scientific production of mankind thill that date (De Meis, 2008).

However, in the year 1900, the estimated number of scientists in the world was 4-5000 and their scientific production was published in scientific journals of wide circulation, and that could be found in the main world libraries. In that specific year, 4000 articles were published (De Meis, 2008). This institutionalization of science lead to an exponential growth of scientific enterprise and In the 20th century, the number of scientists was estimated to be 30 million, publishing astonishing 2 million articles a year.

And all this information has changed our way of living in this planet. We went from 6.8 km.h-1 (the speed of running with our own legs) to 25 km.h-1 in ancient Mesopotamia (war chariots with 2-3 horses). The steam engine reached this speed only in 1925. But after that, in an interval of less than 100 years, man reached space in rockets that could reach 200.000 km.h-1 (De Meis, 2008).

The current model of science funding was established after the 2nd world war, by the United States. The success of the Manhattan project as an applied science initiative, and the understanding that ultimately the war was won by science, lead to the understanding of the strategic importance of science for a country sovereignty and the importance to create the means to continuously funding basic science that could lead to applied solutions (Bush, 1945). The model of a ministry of science and technology and a National Science Agency was copied throughout the world and until today is the mainstream, with grants distributed to scientists according to their previous achievements.

In spite of all the benefits that basic and applied science brought to us in the 20th century, it has created several vice and bias. Researchers learned that money was distributed on the basis of some indexes (like number of publications and their impact factor) and started to specialize and produce theses indexes instead of knowledge. The result is that today we have the biggest credibility crisis in the history of science (Munafò et al., 2017; Begley and Ellis, 2012; Prinz et al., 2011) and a system that exclude women and young researchers and gives a lot of power to journal editors and publishing houses.

Moreover, universities and research institutes are not growing at the same pace of the number of scientists (measured ad people with a PhD) and even though this many suggest we already have enough scientists, this is not true. Data from OECD shows the best indication for innovation (measured as number of patents) is not R&D investment, number of published articles or even previous achievements (such as other patents): is the number of scientists (OECD, 2010). The average rate of scientists in the world is 1k/1M inhabitants. The 5 nations that produce most of the knowledge in the world (measured again as number of patents), have 5-times this average. Developing countries, such as Brazil, have half the average (OECD, 2010). If these nations wants to join the knowledge economy in the 21st century, they will have to drastically increase the number of scientists, even though they lack the infrastructure (universities and research institutes) to do so.

In the article ' Data is giving rise to a new economy', in 'The Economist', the authors shows that 10 years ago the 10 biggest companies in the world were oil companies. Today, the five biggest ones are data companies. Already today, data is a commodity more valuable than oil and we have every reason to believe it will continue to be like this in the knowledge economy of the 21st century.

How can we leap-frog science in a de-infrastructure world? With technology and the new modes of operation that technology allow us. Internet gave us the opportunity to connect in an unprecedented manner. New media allowed us to regain authorship. Social networks allowed us to crowdfund, crowdwork and crowdsource ideas, projects and businesses. Now, blockchain let us bring full transparency to initiatives, at the same time they retain privacy and data security; as well as give us the means to finance this new models with cryptocurrencies. The world is now set for crowdscience and that is why we want to bring to the world Genecoin.

Most the innovation that the 20th century brought to us came from physics and chemistry. Even though they allowed amazing things, like nuclear energy, transportation, and food production, there are recalcitrant problems to which they cannot offer sustainable solutions. The biological revolution that started with the unveiling of the DNA structure in 1953 (Watson and Crick, 1953) and led to the first recombinant organisms in 1980's and the sequence of the entire human genome in 2001 open the doors to an entire new economy, with the potential to solve every single problem on the planet: bioeconomy.

OECD, in its Bioeconomy 2030 report (OECD, 2009), estimates that 35% of all chemicals, 80% of all pharmaceuticals and 50% of all agricultural output will come from biotech, contributing with almost 3% of OECD GDP. These figures could be underestimated since biofuels and unpredicted applications cannot be accounted.

These solutions are based on the premises that live on the planet has 4 billion years and during this period, it has faced and solved every possible problem that life could face. The solution to these problems are stored in the DNA of the species. Accessing their genomes could unlock these knowledge and create new solutions to old and new problems. Genomes are the ultimate form of biodiversity and the repository of its information. Decoding genomes thus is of extreme importance and value.

" There are between 5 million and 30 million species on Earth, each one containing many thousands of genes. However, fewer than 2 million species have been described, and knowledge of the global distribution of species is limited. History reveals that less than 1% of species have provided the basic resources for the development of all civilizations thus far, so it is reasonable to expect that the application of new technologies to the exploration of the currently unidentified and overwhelming majority of species will yield many more benefits for humanity. [...] This approach, which exploits the vast databases of natural history together with ecological and evolutionary theory, has been given a variety of names, including ecologically driven drug discovery, the biorational approach, and hypothesis-driven drug discovery (Beattie et al., 2005)."

Pharma industry is one example of high prize for drug discovery. More than 50% of all prescribed drugs in the US have active principles coming from plants (Griffo et al., 1997). Captopril is part of the selected list of blockbuster drugs that were developed for U$600 M after a principle extracted from the Brazilian snake Jararaca venom and has a annual revenue of U$5B. What are the odds we will find a new drug or product if we could sequence everything? The size of the market locked in tropical forest is actually estimated to be $109 billion (Mendelsohn and Balick, 1995)

We don't need to actually calculate to know that it is high. The thing is that now we can sequence everything.

As DNA sequencing prices goes down at a speed 10 times faster than Moore's law ( see figure in Wetterstrand, 2014) we will be able to, very soon, sequence every living organism on earth.

There are several k projects and they are moving fast to million. The Beijing Genomics Institute - BGI has sequenced 3000 rice genomes, the '10k genome consortium' is aiming to create a genetic 'Noah's Arc' of biodiversity, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals is among the companies that are carrying on their own 100k human genome projects and, in a dispute similar to the one that sequenced the whole human genome in 2001, Barack Obama gave more than U$100 M dollars for NIH to create a '1 Million human genomes' project, while Craig Venter announced a company with U$70 M investment to sequence 100k human genomes a year.

we published a pre-print with a simplified version of the genome of 50 species of the Atlantic forest (Detoni et al., 2016). It took us 6 moths to do it and we showed that we can find enzymes from major terpene production pathways in the unique databank of Atlantic forest species we have created. We can now scale-up the sampling, sequencing and bioinformatic pathway to sequence 100, 1000 10.000 species.

I'd like to finish this session with and impressive number: Tripp and Grueber, (2011) showed on their report 'The Economic Impact of the Human Genome', that a $3.8B Investment in Human Genome Project drove $796B in economic impact creating 310,000 jobs and launching the genomic revolution. An investment of almost U$4 billion over 10 years has created, after 10 years, an economic impact of almost 1 trillion dollars. That is an amazing IRR.

The challenges of studying Genomes and building the 21st century bioeconomy

If we agree that bioeconomy is strongly related to genome Sequencing, assembling, annotating and interpreting, than we must face the challenges that it poses to us.

- At the same time, the cost of analyzing this data grows ( see figure in Sboner et al., 2011), and to date there is no solution to the problem of processing all this data. That includes the problem of storing huge amounts of data and making this data available online to everyone.

- Countries with a lot of biodiversity, like Brazil, have far less scientists per capita than the world average ( see figure with UNESCO, 2015) and that limits the ability to process all this information locally.

- Finally, with few exceptions, research funds have been shrinking all over the world ( see figure with UNESCO 2015). Existing funds are centralized in granting agencies and distributed according to biased criteria that favors the status quo.

In spite of the opportunities that technology offers to innovate, science is usually less prone to embrace it in early stages. We have been expectators in the blockchain movement and we wanted to use the power of this new technology to foster opportunities in science. We believe that blockchain and cryptocurrencies can allow us to bring together crowdfunding, crowdsourcing and crowdworking in a much faster, simpler and safer way, creating the concept of crowdscience.

It would benefit immediately thousands of scientists, especially the young ones that take too long to enter in the traditional funding system, to carry on the important research we need to solve the problems we will continuously face in the XXI century.

Science has always been a chain of blocks of ideas. Sometimes, there are reasons to "soft fork" theories, other times, to "hard fork" them to explain different magnitudes of events. Validation come from the "full nodes" of research groups and institutions that can see the previous idea block that was proposed, and perform further experiments confirm them or not. In general, the longer and more established chain prevail, but there is always the possibility to go back to a certain point in time or to find orphan idea blocks that can lead to a new theory or was not at first fully understood. If we think about all of that, science is ready for a new way to convey its resources and all its scalability. There are no borders for knowledge, only from time to time, when some try to impose on it. There is a common language on data, equations, and even on social theories that can prime an unprecedented future.

We list here some value propositions according to the categories created by Almquist et al., (2016). Genecoin has the power to propose value in all four categories of the scale:

- Self-transcendence: Helping other people or society more broadly - The 310,000 jobs created by the genomic revolution and the $796B in economic impact after the publication of the Human Genome Project is an example of the broad and distributed impact that genome projects can have in the society.

- Affiliation and Belonging: Helping people become part of a group or identify with people they admire - Lay citizens can participate in complex scientific problem solving, contributing to solve a real problem in the real world. A good example was our successful scientific crowdfunding in Brazil in 2013 to sequence an animal genome, as well as the many other scientific crowdfunding projects that came before and after. It brings lay citizens closer to science and scientists and vice versa.

- Self-actualization: Providing a sense of personal accomplishment or improvement - A free, valuable, mobile currency will allow tenths, hundreds, thousands of researchers to practice and improve their knowledge while participating in decentralised research projects, in spite where their location and currency. They will be part of the solution of a bigger problem at the same time that they improve themselves. Besides that, they will learn about cryptocurrencies, blockchain and decentralised marketplaces.

- Provides Hope: Providing something to be optimistic about - Development of new technology through science is the only hope that one day we will be able to better fight disease, climate change, invasive species; secure food and produce clean energy and so on. Genecoin represents a new way to crowdfund and movement a science market and ecosystem.

- Provides Access: Providing access to information, goods, services or other valuable items - In a world overloaded with information, to have data published and public does not guarantee easy or continued access to it. You still need to be able to find the holder of the information and know how to access it. The information is also centralized: if one day the journal cease to exist, that information will be no longer available. Genecoin allows its founders to finance projects such as the Genome hyperledger (see below), that can solves the storage and access problem of big genomic data by transferring it to the blockchain. Information will always be there and anyone can develop tools to better access and use it. Forever!

- Reduces Anxiety: Helping people worry less and feel more secure - Scientist are though by other scientists to pursue a career in academia. Nevertheless, only 3% of PhD will find this positions. Many will find jobs outside science, wasting precious resources invested in a lifetime of education. Anxiety about career perspectives is incredibly high among PhD students and influences everything: from dropouts to fraude in scientific data (De Meis et al., 2003; Levecque et al., 2017). Young, devoted, active, brilliant scientists waste their most productive years doing fundraising instead of researching. Probably for nothing, since a new survey in Nature indicates that only 3% of PhDs are likely to get a stable posting on in academia (Editorial, 2017). Genecoin present young researchers the opportunity to work online, wherever they are, complementing their income, reducing stress, accomplishing scientific goals independently of their institutions and their PI, nationality or any other.

- Fun / Entertainment: Offering fun or entertainment - I'm sorry, but we have to say it like this: Genecoin is fucking awesome!

- Saves Time: Saving time in tasks or transactions - The blockchain is great strategy to consolidate information. Searching for information is, nowadays, one of the main reasons to waste time (Dalkir, 2011). For example, it is estimated that using collaborative tools such as Google Docs reduces in 4-fold the time required to find versions of documents. Genecoin will allow the blockchain transactions that will store and give access to information in the most transparent and secure manner.

- Simplifies: Reducing complexity and simplifying; Organizes: Becoming more organized; Connects: Connecting with other people; Reduces Effort: Getting things done with less effort - The blockchain technology allows creation of decentralised marketplaces that can simplify, organize and connect people, reducing effort considerably. Information, users, sponsors and everyone else in a decentralized, unbiased, trustworthy structure. Supply and demand decentralised, but together in one place. Genecoin is the means to allow such a marketplace to exist and function.

- Reduces Cost: Saving money in purchases, fees or subscriptions - Because it is digital, mobile and backed by blockchain, Genecoin has minimum transaction cost. It is the cheapest possible way to transfer and store value.

- Informs: Providing reliable and trusted information about a topic. Blockchain storage and marketplaces can be the ultimate repository for trustworthy information that will help scientists accomplish their goals. Genecoin is the monetary tool that allows this to exist

- Makes Money: Helping to make money - Eventually, it will become a way for researchers to make money. Genecoin would give the opportunity for a scientist become an autonomous researcher working in marketplaces or peer-to-peer with anyone, anywhere, anytime, receiving safely in Genecoin.

Research has always been collaborative, but there are several limitations to carry on this collaborations across borders even in connected times, especially concerning the movement of funds. How to pay a Pakistani bioinformatician with Brazilian research funds? And vice-versa? Fees, taxes and bureaucracy makes it impossible for scientists from some countries to work in a competitive fashion.

A currency has the power to bring people together. As Harari wrote in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Harari, 2015) "Money is the most universal and most efficient system of mutual trust ever devised. [...] Be that as it may, money is also the apogee of human tolerance. Money is more open-minded than language, state laws, cultural codes, religious beliefs and social habits. Money is the only trust system created by humans that can bridge almost any cultural gap, and that does not discriminate on the basis of religion, gender, race, age or sexual orientation. Thanks to money, even people who don't know each other and don't trust each other can nevertheless cooperate effectively."

Social currencies are instruments or payment systems created and administered by end-users in economic relationships based on cooperation and solidarity of the participants of certain communities. Genecoin is the currency of the scientific community and all the people that collaborate with this community. Genecoin is based on the principles of freedom of association and freedom of contract, and is perfectly legal in most countries. As a social currency, Genecoin can be used to confront some structural weaknesses present in monetary systems. Like other social currencies, it is tolerated by central banks, in order to protect the user community, stimulate exchanges and transform the nature of those exchanges (Freire, 2011). Also, when applied to traditional populations receiving distribution of benefits on the basis of The "Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity", Genecoin can be used to strengthen the economy of those traditional populations. But more than a social currency, Genecoin is not local, but global; it serves a community that runs a real economy, with no borders, with huge diversity, but having one thing in common: love for science.

Through Genecoin, researchers, entrepreneurs, lay citizens (actually, anyone) can collaborate to move a knowledge economy.

- Keith is a philanthropist and a believer that science is the way to move forward. He wants to support research in low back pain and found out that some plants from tropical forest offers new possibility of anti-inflammatory drugs. He wants to donate for the Digital Forest project, that is placed in Brazil and is sequencing tropical forest genomes. He uses Genecoin to make his donations arrive to the project researchers. The donation arrives to them instantly, at a minimum transaction cost.

- David is the property owner that owns the actual forest. He is a believer that the Forest worths more standing than put down. He knows that only through the creation of high aggregate value products he will have the revenue that is necessary to fuel a sustainable business model. So he invested in sequencing the DNA from the Forest species. When doing so, he had a 20% discount because he was paying in Genecoin.

- Antonio is from a traditional community and lives in the Forest. He was hired to collect the samples that were sent to the DNA sequencing lab. Antonio is very smart, even though he lacks formal education. He knows all the plants in the forest and is the most indicated person for the task. Antonio is part of the 'unbanked' population, which makes very difficult for him do receive money and pay his bills. Specially being far from urban centers. However, he has a smartphone and an internet connection. David has no difficult to pay Antonio with Genecoin.

- Suzan is the managing director at BioMolCo, the company hired by David to sequence the genomes of the Forest. At first, Suzan hesitated to accept a cryptocurrency. Those documentaries showing how Bitcoin was being used by drug-dealers in the dark web didn't help. However, leading a biotech company, she could not be tech averse. She was convinced by her CTO that blockchain was not only safe, it was a revolutionary technology and that cryptocurrencies were far more reliable than fiat money. She started accepting partial payment in Genecoin and confirmed all the advantages of the cryptocurrency: no bank fees, no bank delay, very low transaction cost, registration of the transaction in the blockchain. She is expecting that her suppliers starts to accept Genecoin so she can fully migrate to the digital currency.

- Beth is one of this suppliers. She is bioinformatician and a freelancer scientist that works for BioMolCo. She is doing her PhD and is taking a summer course abroad. Because much of the tasks are done online, being abroad is not a problem for her. However, spending her earnings was. She used to have to move her payment from her original bank to her current location, and that was a bureaucratic, time consuming and expensive process. If she had executed some microtask on a marketplace, even worse, because the transaction cost was sometimes larger than the amount of money. She decided to accept some tasks in Genecoin so she avoids all the hassles of bank transactions. After a while, she realized all the benefits of digital currency and even now that she is back home, she only wants genecoins.

- Mark is another supplier. He is a lawyer and his office is dedicated to several topics related to law, one being access the biodiversity and genetic heritage. Mark wanted to know more about cryptocurrency and its potential as an investment and a way of safeguarding value. He realised the best way to do it was not buying cryptocurrency with fiat money, but to accept it as payment for his work in specific topics or situations. He started to accept 20% of his fees in Genecoin in procedures that were related to biodiversity access or innovation. Now he has a hard wallet with an array of different currencies and is considering receiving full payment in crypto.

- Paulo is the head of the research laboratory that is involved in anti-inflammatory research. He was the one to suggest his donor Keith to make the transaction in Genecoin. After suffering for many years with the bureaucracy of foundations and the paying of receiving in a weak fiat currency and importing reagents and equipment in a strong fiat currency, he was more than willing to try the new system when he first heard of it. He immediately saw the potential to use digital currency to hire tasks from researchers abroad, hire services in strong currency and foster collaboration. He can also complement the salary of his students with cryptocurrency. He is now helping other scientists to embrace the new system.

- Joana is a programmer and all she needs to work is her computer and a good internet connection. Being a digital nomad, she is used to staying 3 months in one city/country and 4 months somewhere else. She only managed to choose this innovative life style because she was an early adopter of cryptocurrencies.

- Andre is a 'miner'. He believes in the technology and the concept of cryptocurrencies so he decided to lend his idley computer power to mine the hyperledger of the genomes. For this operation, he is paid in genecoins. Discounting the electricity bill and the use of the computer, he still makes money… almost without doing anything. He is paid because 'mining' is the nickname of the proof-of-work process that is the keystone of blockchain, guarantee its safety and confidence.

- Michael is an entrepreneur. He foresaw a business opportunity for the new anti-inflammatory and wants to develop it as a business. He is going to ICO his new company and because genecoin is already accepted by the ecosystem, he decided to use it for the fundraising.

- Manoel is the community leader of the traditional population that lives in the forest. He is responsible for negotiating the Benefit Share contracts according to the Nagoya protocol or the National law that they have. He choose to have Genecoin as a currency because he can than have smart-contracts that will guarantee the payments in cryptocurrency and are not subject to manipulation or fraud, besides all the advantages of having a cryptocurrency that Antonio has.

- Erick is the publisher of a Open Access scientific journal. He decided to accept Genecoin for the publishing fees because it will allow him to create a pay-per-review system, solving a major bottleneck in science journals today.

- Smith is a reviewer in Ericks journal and is happy in, instead of reviewing articles for free, receiving Genecoins for it. His time and expertise can be converted in a cryptocurrency that can finance other activities on his research.

The beauty of Genecoin is that it is the glue that puts all these parts together. And the seed that allows all this ecosystem to grow and flourish.

The development of Genecoin's ecosystem will be proportional to the resources raised during the ICO using the Scrum methodology.

In our development environment in Github ( https://github.com/orgs/genecoin-science/dashboard) you can find the backlog of the development as well as the dynamic list of tasks assigned to every sprint.

We believe that the main metric to evaluate Genecoin's success is the number of transactions in the currency. That is why the main commitment of the founders with the backers is to work to have scientists creating stores in the proof suite to offer their services to the scientific community in Genecoins.

The development of the project will be directly communicated to the community through our twitter.

We are confident we will be able to develop the following projects to kickstart the ecosystem:

- Hyperledger of the Golden mussel genome (see box below) - The cost and time of mining a huge genome file could make introducing it in the Bitcoin or the Ethereum blockchain, unviable. It is possible to create a private blockchain, but than you lack the miners community that give confidence and safety to the information. A workaround of that is to create an hyperledger, a system of parallel blockchains that stores the information registering in the main blockchain (in our case ethereum), just the public access keys. - Deadline: 9 months after ICO

- Genome window - An interface to display the genes, and the meta information associated to them, in a consolidated manner, that were stored on the blockchain. The purpose of this interface is to make information easily accessible to whoever wants to use it. Deadline: 12 months after ICO.

- Note: We believe this two initial tasks help solve a major bottleneck in scientific world today, which is the centralization of databanks and platform projects, that depend on continuous grants to keep updating their data and make their information available. By transferring the genetic information to the blockchain, we will make it available for everyone, without central management, for unlimited time, forever. And leave to the crowd the task of continuously improving the information.

- The Scientometrics smart contracts - An app that will suggest 'researchers' fit to perform tasks according to 'backers' wishes. This app will use Scientometrics to select the most adequate researchers based on their academic background, scientific production and so on. Deadline: 4 months after ICO.

- GRAppE marketplace - In more 'cold' terms, GRAppE will be a set of smart-contracts (mostly coded in Solidity) and software interfaces (most likely in Python) running in to the blockchain. Each product will be planned to be completely autonomous and to run without the interference of a human. Smart contracts will enable us to facilitate a payment solution working flawlessly between parties via the Ethereum blockchain. A marketplace software, in which users with knowledge about the DNA sequences and their relation to molecular biology, biochemistry, physiology, ecology, etc, could take a sequence, made public by them or by someone else, and improve it, by validating the initial assembly, annotation and metadata, or any other claims. Deadline: 18 months after ICO.

- From genomes, to genes, to blocks - A smart-contract that will manage the transaction of registering a gene sequence with metadata to the blockchain, between the 'user' that offered the sequence and the 'backer' that is sponsoring its inclusion in the blockchain; as well as the Ethereum block creation fee. The code that select one or more DNA sequences (fragment, singleton or genes) from our genome database and published in the blockchain for anyone, anywhere in the world to use it for research or any other purposes (developing new technologies or businesses), has to be included in the smart-contract. Deadline: 4 months after ICO.

Four years ago, we decided to crowdfund our main research project: the sequencing, assembling and annotation of the genome of an aggressive invasive species, the Golden Mussel Limnoperna fortunei. This small bivalve mollusk ( see image) has travelled from China in ballast water of cargo ships to invade South America waters, leaving a trail of environmental damage and economical losses where it passes. You can learn more about the invasion and the risk of reaching Amazo waters in this review article that we published in 2013 (Uliano-Silva et al., 2013) and watching the video that we prepared for the crowdfund campaign. We carried out the first successful scientific crowdfund campaign in Brazil, raising USD 20k we needed for the sequencing part of the project. Other resources came from research grants in Brazil and abroad. We believe the success of the crowdfunding campaign was partially due to the strong science communication component, as well as the project oriented goals of the research. We were very careful to properly communicate to the general public the problem, the project, our reasons to do it and what we would do with the money. Besides all the spontaneous media that the project received (see further reading section), the researcher conducting the project was selected as TED fellow and spoke in TED global. We finished sequencing, assembling and annotating the best bivalve genome to date. A huge accomplishment for a small group of molecular biologists and bioinformaticians that we are. The article has been accepted for publication in GigaScience and is available already in pre-print version in PeerJ (Uliano-Silva et al., 2017). It is not going to be the first genome on the blockchain, but it will definitely be the best.

Guarantee Liquidity and progressive discount rate - a positive entropy financial model

The competitive differential of Genecoin as a currency is its the guarantee liquidity of its tokens at a progressive discounted rate. This will significantly reduce investment risk at the same time that increase value of the asset.

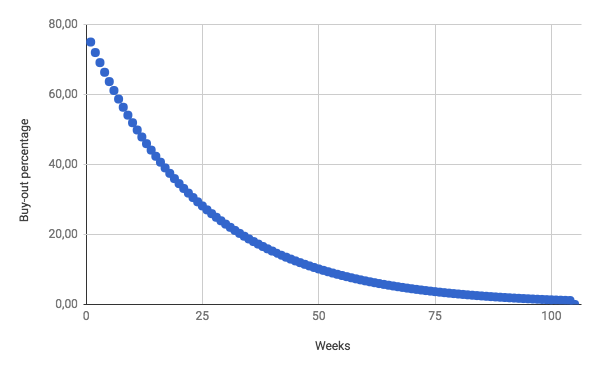

The discount rate will start at 25%, to compensate for the founders and development tokens, and will gradually increase at a rate of 4% a week (see graph below) with the premise that everyday the risk of owning Genecoins is lower. The discount rate will reach 100% after 104 weeks or 2 years. The buyouts are going to be executed by a smart-contract (to be developed).

Even though any token holder can buy out at anytime, restitutions will carried out in batches, to prevent eroding the resources with transaction fees. Any token holder, actually anyone, can check the token statement at any time, through etherscan.

Founders and development tokens will be in a multisignature contract that prevent token dump and reduce volatility risk.

There will be no fractionary deposits of any kind.

Genecoin will be ballasted in Ethereum, thus following its variations.

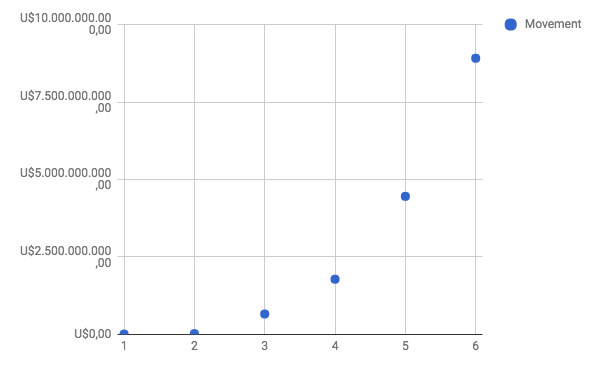

Scientists are a big market. OECD estimates there are around 11.000.000 scientists in the world. Given that the world's expenditure in research and development is about 2.2% of the world's GDP (2014 data from data.worldbank.org), and that world's GDP was around 79 trillion dollars in 2014, we can estimate that these scientists movements almost 2 trillion dollars a year. In developing countries these markets may be smaller, but still very big. Brazil has invested about 1% of its GDP in R&D expenditures. In 2014 that was equal to 26 Billion dollars. If we expect to get even a very thin slice of these markets (0.05% of just the Brazilian market in the 1st year), that would mean a marketcap of more than 13 million dollars. That is only 14k scientists (the amount of researchers that receive "productivity" research grants in Brazil, considered the top researchers in each field of study) spending less than one thousand dollars a year in genecoin. And Brazil has around 300.000 PhD registered in the national research council database, so this figures could be easily higher.

In 6 years, with only 0.5% of the world's scientific community operating in Genecoin, its marketcap could surpass 10 billion dollars.

One hundred million (100,000,000) tokens have been issued in the Ethereum platform. Founders will hold 10% of the Tokens and other 15% of tokens will be used for developing and distributed among supporters. Genecoin symbol will be GEN.

Prices will be set in Ethereum and stored in the smart-contract to guarantee liquidity.

You must have a wallet to acquire Genecoins. MyEtherWallet or MetaMask will work perfectly.

We will work to list Genecoin in exchanges 60 days after ICO.

At this first stage, word-of-mouth through social networks will be the main marketing strategy. In the future, we can think of marketing or connecting actions triggered by the smart contracts.

Like in every other possible social application of the blockchain technology, every laboratory could become an DApp or a DAO, open to collaboration with every researcher in the world, in spite of distance, specialty, currency, location, language.

It could allow scientists and DApps from benefiting from other blockchain technologies. They could use Gole m for computer processing; Filecoin for storage, Namecoin for copyright and authorship.

It means independence of thought and freedom of speech. No more blind reviewers. No more publisher fees. No more importation taxes. No more 'earning in weak currency and spending in strong one'.

An independent researcher could use the cryptocurrency fund to work in a garage lab, such as Biocurious and GeneSpace in USA, and Garoa Biohacking in Brazil, to carry on experiments and than have sponsors paying to 'release' this information to the public in the blockchain.

We may not have enough space in this white paper to discuss every aspect of the impact that bringing science to the blockchain can have. We rather leave this section for you, users of Genecoin, to write.

Genecoin is a complementary currency. Genecoin tokens do not have the legal qualification of a security, since it does not give any rights to dividends, interests, shares or votes.

Cryptocurrencies are subject to high volatility. It is strongly recommended that you get familiar with cryptocurrencies before acquiring Genecoin to fully understand its mechanism and risks. Including the risk of wrong transactions, wallet hacking and the extremely unlikely event of blockchain hacking.

In particular, the Genecoin may not be able to launch or complete its projects as promised. Therefore, and prior to acquiring Genecoin tokens, any user should carefully consider the risks, costs and benefits of acquiring Genecoin tokens in the context of the crowdsale and, if necessary, obtain any independent advice in this regard. Any interested person who is not in the position to accept or to understand the risks associated with the activity or any other risks as indicated in the Terms & Conditions of the crowdsale should not acquire Genecoin tokens.

We hope that our previous experience in delivering scientific crowdfunding, as well as a public (academic or not) careers, make us worth of your trust.

This white paper shall not and cannot be considered as an invitation to enter into an investment. It does not constitute or relate in any way nor should it be considered as an offering of securities in any jurisdiction. This white paper does not include or contain any information or indication that might be considered as a recommendation or that might be used as a basis for any investment decision. Any information in the white paper is provided for general information purposes only and is not to be considered as an advisor in any legal, tax or financial matters. Neither it provides any warranty as to the accuracy and completeness of this information.

By participating in the crowdsale, the purchasers agree to the above and in particular, they represent and warrant that they:

- are authorized and have full power to purchase Genecoin tokens according to the laws that apply in their jurisdiction of domicile;

- live in a jurisdiction which allows to sell Genecoin tokens through a crowdsale without requiring any local authorization;

- are familiar with all related regulations in the specific jurisdiction in which they are based and that purchasing cryptographic tokens in that jurisdiction is not prohibited, restricted or subject to additional conditions of any kind;

- will not use the crowdsale for any illegal activity, including but not limited to money laundering and the financing of terrorism;

- have sufficient knowledge about the nature of the cryptographic tokens and have significant experience with, and functional understanding of, the usage and intricacies of dealing with cryptographic tokens and currencies and blockchain-based systems and services;

- Almquist E, Senior J, Bloch N. 2016. The Elements of Value. Harvard Business Review. September issue https://hbr.org/2016/09/the-elements-of-value accessed 12/01/2017

- Beattie AJ, Barthlott W, Elisabetsky E, Farrel R, Kheng CT, Prance I. 2005. New Products and Industries from Biodiversity. In: Hassan R, Scholes R and Ash N (eds) Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends, Vol. I, Island Press, Washington DC. Chapter 10

- Begley CG., Ellis LM. 2012. Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature 483:531.

- Bush, V. 1945. As we may think. The Atlantic Monthly; 176(1): 101-108

- wDalkir, K. 2011. Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice. The MIT Press; second edition edition. 504 pp

- de Meis, L., Velloso, A., Lannes, D., Carmo, M.S., & de Meis, C.. (2003). The growing competition in Brazilian science: rites of passage, stress and burnout. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 36(9), 1135-1141. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-879X2003000900001 accessed 12/01/2017

- De Meis, L. 2008. Ciência, Educação e o conflito humano-tecnológico. era edition Senac. São Paulo. 145pp

- Detoni MAA, Cardenas RGCCL, Uliano-Silva M, de Freitas Rebelo M. (2016) Gene discovery in Atlantic Forest plant species using GR-RSC simplified genomes. PeerJ Preprints 4:e2316v1 https://dx.doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2316v1 accessed 12/01/2017

-

- Many junior scientists need to take a hard look at their job prospects Nature 550, 429 doi:10.1038/550429a

- Freire, Marusa Vasconcelos. MOEDAS SOCIAIS: Contributo em prol de um marco legal e regulatório para as moedas sociais circulantes locais no Brasil. Tese de Doutorado em Direito Brasilia, UnB, 2011. http://repositorio.unb.br/bitstream/10482/9485/1/2011_MarusaVasconcelosFreire.pdf accessed 12/01/2017

- Grifo F, Newman D, Fairfield A, Bhattacharya B, Grupenhoff J. The origins of prescription drugs. In: Grifo F, Rosenthal J, editors. Biodiversity and Human Health. Washington, DC: Island Press; 1997. pp. 131–163.

- Harari, Yuval N., author. (2015). Sapiens : a brief history of humankind. New York :Harper,

- Levecque K., Anseel F., De Beuckelaer A., Van der Heyden J., Gisle L. 2017. Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research Policy 46:868–879. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.008.

- Mendelsohn, R., & Balick, M. J. (1995). The value of undiscovered pharmaceuticals in tropical forests. Economic Botany, 49(2), 223–228. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862929 accessed 12/01/2017

- Munafò MR., Nosek BA., Bishop DVM., Button KS., Chambers CD., Percie du Sert N., Simonsohn U., Wagenmakers E-J., Ware JJ., Ioannidis JPA. 2017. A manifesto for reproducible science. Nature Human Behaviour 1:21.

- OECD (2009), The Bioeconomy to 2030: Designing a Policy Agenda, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264056886-en accessed 12/01/2017

- OECD (2010), Measuring Innovation: A New Perspective, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264059474-en accessed 12/01/2017

- Prinz F., Schlange T., Asadullah K. 2011. Believe it or not: how much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 10:712.

- Sboner A, Mu XJ, Greenbaum D, Auerbach RK, Gerstein MB. 2011. The real cost of sequencing: higher than you think! Genome Biology 201112:125 https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-125 accessed 12/01/2017

- Tripp, S. and Grueber, M. (2011). Economic Impact of the Human Genome Project. Technical report, Battelle Memorial Institute.

- Uliano da Silva M, Dondero F, Otto T, Costa I, Lima NC, Americo JA, Mazzoni C, Prosdocimi F, Rebelo MF. (2017) A hybrid-hierarchical genome assembly strategy to sequence the invasive golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei. PeerJ Preprints 5:e2995v1 https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2995v1 accessed 12/01/2017

- Uliano-Silva M, Fernandes FC, Holanda IBB, Rebelo MF. 2013. Biological invasions. How invasive species threaten biodiversity: The case of the golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei and the Amazon River basin. In Allodi S: Exploring Themes on Aquatic Toxicology., Chapter: 8, Kerala: Research Signpost. 143-157. DOI: https://doi.dx.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1511.5923 accessed 12/01/2017

- UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf accessed 12/01/2017

- Watson JD., Crick FHC. 1953. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids. Nature 171:737–738.

- Wetterstrand, K. (2014). DNA sequencing costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP). Technical report, NIH. https://www.genome.gov/sequencingcostsdata/ accessed 12/01/2017