How many carbs in that cookery book recipe? This app tells you!

Take a photo of the ingredient list from a recipe with your phone, and the app will calculate the number of carbs in the recipe. It will also show a breakdown of carbs in each ingredient, allowing you to see where the carbs are coming from.

You can edit the ingredient list after you scanned it in - this can be useful if an ingredient is not recognized, or if you want to add or remove ingredients.

The app will try to detect the number of servings - but you can override that too.

If a food is not recognized, then as a fallback you can append the carb factor of the food in square brackets at the end of the line. For example, "200g freekeh [60]" tells Ingreedy that freekeh has 60g of carbs per 100g, so there will be 120g of carbs for that line. You can typically find the carb factor of a food by searching on Google for "[food] carbs per 100g".

This project is an extension and follow on from my original Ingreedy project that I wrote to make it easy to calculate carbs from recipes. The original Ingreedy has no OCR facility, so you have to type in the ingredients list. It also allows you to save recipes, books, and add new foods to the database.

Ingreedy-js is quicker to use, but less fully-featured, and is ideal to get a rough estimate of the carb count for a recipe.

The app is a web application written in HTML and Javascript. Apart from an API call to Google's Vision API, the whole app runs locally in a browser on a phone or on a laptop. If you don't have a API key then the app falls back to manual mode where you have to type in the ingredients list.

The user takes a photo of a recipe, then it is displayed in the app. There is some code that fixes the orientation of the image (see the discussion here).

After the user has taken a photo, it is uploaded to Google's Vision API to convert it to text. The Vision API returns a rich JSON representation of the document. A document is composed of blocks, which are themselves broken into paragraphs, then words, then symbols.

This hierarchy allows us to use layout cues to help with finding and parsing information about the recipe. The main goal is to find the list of ingredients from the photo, and ignore extraneous information such as recipe directions, which tend to be in separate blocks. We also want to find the number of servings that the recipe makes, which is often (but not always) contained in a separate block to the ingredients.

We cannot assume that all the blocks of text in the image are ingredient lists, since the user may capture other recipe information like the name of the recipe, a description of the recipe, or the directions for making the recipe.

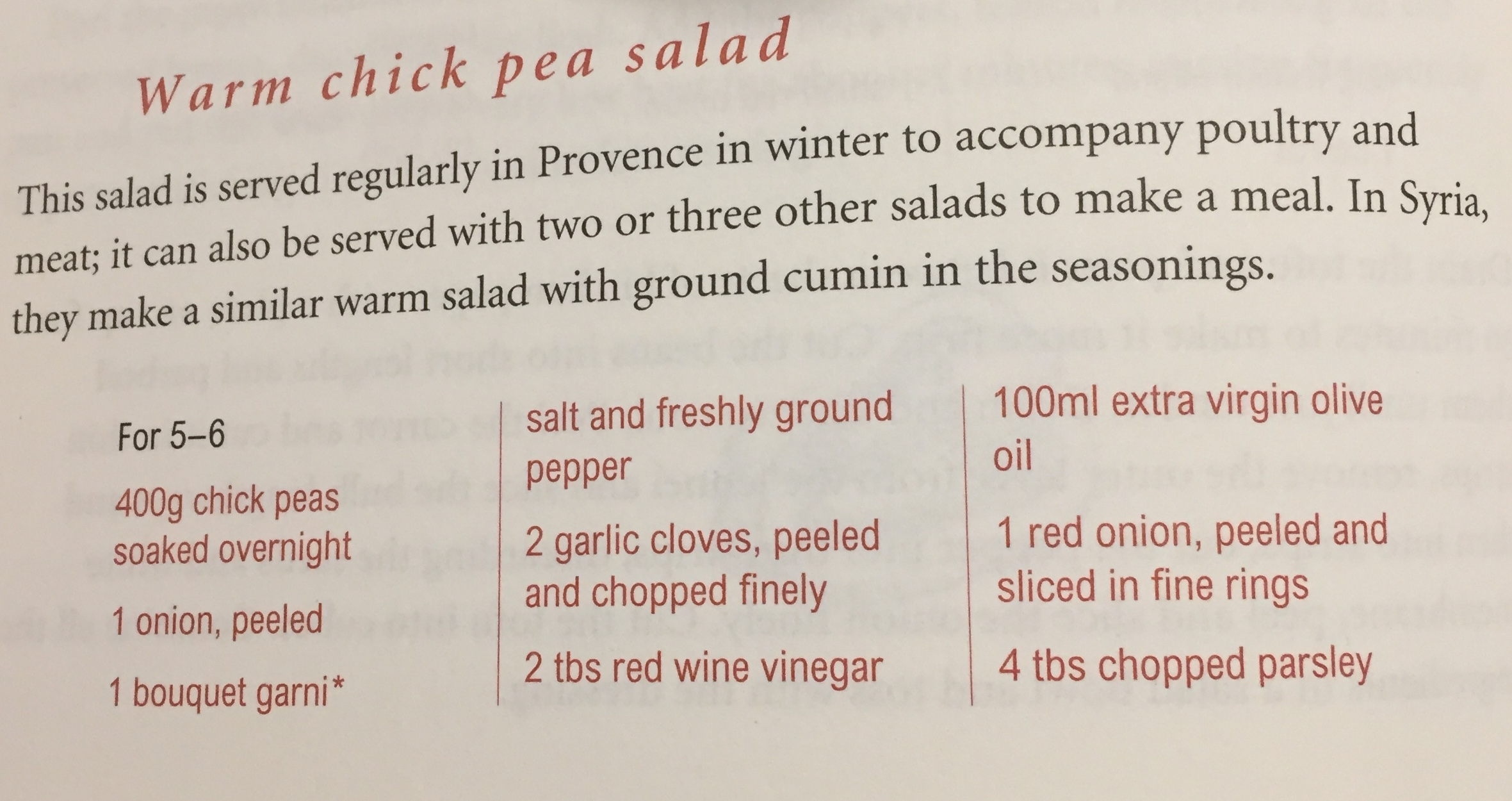

The current implementation uses the heuristic that the ingredients list is contained in the block in the centre of the image. This is simple, and works most of the time, especially if users know they should point the camera so it's centred on the ingredients. However, sometimes it is impossible to do this, because the ingredients are spread across different panels:

There may also be separate ingredients lists for different components of a recipe (e.g. for a cake and its icing). For this reason, the user can select the blocks used to construct the ingredients list, by clicking or tapping on them. The blocks highlighted in green are the ones being used.

In the future, it would be nice to investigate an improvement that either uses a heuristic to find blocks that contain ingredients (one possibility would be to look for lines that start with a number, but some recipes have numbered lists for their directions), or a machine learning procedure to classify blocks as "ingredient list" or "not ingredient list".

Many recipes include text like "Serves 4" to indicate the number of servings it will make. We use a simple regular expression and look for matches in all the blocks in the document. If a range is found, like "Serves 4-6", then we choose the lower end of the range (4 in this case) so that the carb count errs on the large side. The user can override the number of servings anyway, which is also needed if no matches are found for the regular expression (in which case we default to a single serving).

This could be improved by making the regular expression more general (if we find other common ways of specifying the number of servings). Machine learning would work too, but might be overkill for this task.

When a block of text has been found that contains a list of ingredients, the next task is to parse each ingredient line and calculate its carb count.

The first thing you realise once you start trying to parse ingredients lines is their sheer variety, which makes it difficult to write a good parser from scratch. While it may be possible to get a long way using rule-based approaches, a lot of work is required to construct a set of rules that works in almost all cases.

Fortunately, there is some prior work that we can take advantage of. The New York Times released code and data from their cooking web site for parsing ingredient lines. Their approach uses conditional random fields (CRF) for extracting the quantity, unit, food, and comments from a line, trained on 170 thousand lines. You can read more about how it works in this excellent blog post.

A major challenge in using their CRF implementation is getting it working in a browser. The CRF implementation they use, CRF++, is written in C++, and there don't seem to be any pure Javascript implementations. This is addressed by using Emscripten to compile CRF++ into Webassembly so it can be run in the browser. (There are notes below for how this is done.)

Once a food string has been found in a ingredients line, we need to find its nutrient data. There are many food nutrient databases available, but the hard part is mapping a (possibly ambiguous) food name to an entry in the database.

For example, a recipes might specify just "flour", but without extra context it's hard to know that this should probably match "Flour, wheat, white, plain, soft" and not, say, "Flour, rice".

To solve this problem we construct a food map from names to food entries. The food map is constructed by taking the NYT ingredient dataset, extracting all of the unique food names, and manually mapping them to food entries in a database. In practice, we restricted to a dataset where each food name appeared at least 10 times. This gave a dataset of 1080 food names, which was not too onerous to manually go through to produce mappings.

Three food databases are used, in priority order:

- The UK Composition of foods integrated dataset (CoFID), by McCance and Widdowson

- The Australian Food Composition Database

- The US FoodData Central

In practice, not all foods appear in the food map, since there is a long tail of very unusual foods. To address this, we use text search against the food database (currently just the UK one). The intuition is as follows: if the food appears in the long tail then it is rare and is likely to have only a single entry in the database. Even if there is more than one entry, they are unlikely to be very different nutritionally. We use lunr for the Javascript search implementation.

The current implementation doesn't consider text from the comments (as found by CRF), which means it can miss important distinctions like "raw" versus "cooked". Curating a good food database is something that needs more work too, since there are always some foods that don't appear in a particular database. Allowing users to add foods is an option here.

Now we have identified the food and its nutrients (and carbs in particular), but we are not done, since we need to determine the quantity used in the recipe. Most of the time this is very straightforward, since we are given a quantity like "500" and a unit like "grams" so we know that's 500g of the ingredient. But there are many other units from the very specific ("tsp") to the vague ("handful"). Sometimes a recipe just specifies a number of a certain foodstuff, as in "5 onions", so we need a database of typical weights for common foods.

The current implementation uses a small set of rules to interpret measures, based on data from the Australian Food Composition Database. Both to map units to weights (e.g. it knows a teaspoon is 5g), and to store common food weights (e.g. it knows an onion is typically 130g).

It's worth noting that some ingredients lines are split over two or more lines, which can complicate matters in some cases. For example, we would like to treat the following as a single line:

100g tamarind paste (the paste should

be the consistency of a ketchup)

In the current implementation these two lines are treated one, since we interpret the indent as a line continuation. Sometimes however there are no indentation hints:

100ml extra virgin olive

oil

The first line might be interpreted as "olive" rather than "olive oil", which could result in inaccurate carb counts. This is quite a difficult problem and it may not be possible to get it right all the time (a possible cue we could use in this case is spacing between lines), so a simple workaround of editing the text after scanning is worth recommending to users.

For each ingredient line, we can now calculate the number of carbs since we know the food entry (and hence the number of carbohydrates in 100g) and the weight needed in the recipe. If any of these things are not known (because we couldn't identify the food, the quantity, or the unit) then that line is marked as "unknown".

The total number of carbs is simply the sum of the carbs for each line. If there are any unknown lines then this is flagged up in the total so the user knows it may not be complete. Unknown lines are marked with red question marks and a hint saying what the problem was, which allows the user to edit the line so it can be re-parsed.

The user interface is a basic HTML application that has been built without using any Javascript frameworks.

One challenge is to make it as easy as possible to compare the original ingredient line, with the OCR'd line, and with the parsed line (quantity/unit/food). On the web this is straightforward, but on a mobile device it is much harder since the horizontal space is very limited. Arguably, the scanned image can be hidden since the original source (the cookery book) is in front of the user, but even doing two-way line comparision is tricky. There is a lot of scope for improvement here.

Install and run a local server with

npm install http-server -g

http-serveror, if you don't have npm:

python -m http.server 8080Then go to http://localhost:8080/?key=KEY in a browser, where KEY is the Google Vision API key.

You will need Node.js.

Then install the dependencies with

npm installBuild the bundle with

npm run buildRun the tests with

npm testYou can run Ingreedy from the command-line as well as the browser.

node tools/ingreedy.js <file>where is a text file containing ingredients lines, or a JSON OCR response from the Google Vision API. To get the latter, run a command like the following:

node tools/ocr.js images/IMG_0096.JPG data/ocr-responses <KEY>You can also run Ingreedy in batch mode across a bunch of OCR responses using commands like this:

node tools/find-outcomes.js data/ocr-responses "unit not found"This is useful for finding systemic problems, like units that are not recognised in this case.

There is also a script for measuring the proportion of ingredients lines that Ingreedy can parse (not necessarily correctly!):

./measure-success.shInstall Emscripten: https://github.com/emscripten-core/emsdk

git clone https://github.com/emscripten-core/emsdk.git

cd emsdk

./emsdk update

./emsdk install latest

./emsdk activate latest

source ./emsdk_env.sh

cd ..Download CRF++ source tar.gz: https://taku910.github.io/crfpp/#source

tar zxf CRF++-0.58.tar.gzBuild

cd CRF++-0.58/

emconfigure ./configure

emmake make

cp .libs/crf_learn .libs/crf_learn.bc

emcc .libs/crf_learn.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_learn.js

cp .libs/crf_test .libs/crf_test.bc

emcc .libs/crf_test.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_test.js

#

emcc .libs/crf_test.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_test.html --preload-file ../model/model_file@model_file --preload-file ../ing.txt@ing.txt -s ALLOW_MEMORY_GROWTH=1 -s ENVIRONMENT=web --emrun

emrun --browser chrome crf_test.html -v 1 -m model_file ing.txt

emrun --browser chrome crf_test.html -v 1 -m model_file -

emcc .libs/crf_test.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_test.html --preload-file ../model/model_file@model_file --preload-file ../ing.txt@ing.txt -s TOTAL_MEMORY=512MB -s ENVIRONMENT=web --no-heap-copy

python ../server.py # fixes wasm mimetype

# open http://localhost:8080/crf_test.html

# Bundle the model file (doesn't work yet)

#emcc .libs/crf_test.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_test.js --preload-file ../model/model_file@model_file

Run

node crf_learn.js --help

node crf_test.js --helpCompile for use in node:

emcc .libs/crf_test.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_test_node.js --embed-file ../model/model_file@model_file --embed-file ../ing.txt@ing.txt -s ENVIRONMENT=node

node crf_test_node.js -v 1 -m model_file ing.txt

emcc .libs/crf_test.bc .libs/libcrfpp.dylib -o crf_test_node.js --embed-file ../model/model_file@model_file --embed-file ../ing.txt@ing.txt -s ENVIRONMENT=node -s MODULARIZE=1 -s 'EXPORT_NAME="MyCode"' -s INVOKE_RUN=0 -s EXPORT_ALL=1

node crf_test_node_program.js