CliFx is a simple to use but powerful framework for building command line applications. Its primary goal is to completely take over the user input layer, letting you focus more on writing your application. This framework uses a declarative approach for defining commands, avoiding excessive boilerplate code and complex configurations.

CliFx is to command line interfaces what ASP.NET Core is to web applications.

- NuGet:

dotnet add package CliFx

- Complete application framework, not just an argument parser

- Requires minimal amount of code to get started

- Resolves commands and options using attributes

- Handles options of various types, including custom types

- Supports multi-level command hierarchies

- Allows cancellation

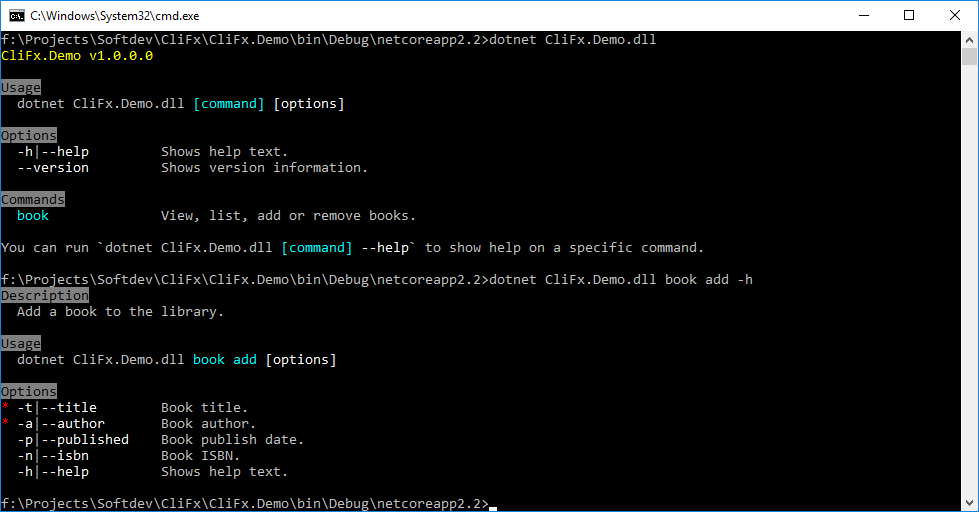

- Generates contextual help text

- Prints errors and routes exit codes on exceptions

- Highly testable and easy to debug

- Targets .NET Framework 4.5+ and .NET Standard 2.0+

- No external dependencies

This library employs a variation of the GNU command line argument syntax. Because CliFx uses a context-unaware parser, the syntax rules are generally more consistent and intuitive.

The following examples are valid for any application created with CliFx:

myapp --foo barsets option"foo"to value"bar"myapp -f barsets option'f'to value"bar"myapp --switchsets option"switch"to valuetruemyapp -ssets option's'to valuetruemyapp -abcsets options'a','b'and'c'to valuetruemyapp -xqf barsets options'x'and'q'to valuetrue, and option'f'to value"bar"myapp -i file1.txt file2.txtsets option'i'to a sequence of values"file1.txt"and"file2.txt"myapp -i file1.txt -i file2.txtsets option'i'to a sequence of values"file1.txt"and"file2.txt"myapp jar new -o cookieinvokes commandjar newand sets option'o'to value"cookie"

To turn your application into a command line interface you need to change your program's Main method so that it delegates execution to CliApplication.

The following code will create and run default CliApplication that will resolve commands defined in the calling assembly. Using fluent interface provided by CliApplicationBuilder you can easily configure different aspects of your application.

public static class Program

{

public static async Task<int> Main(string[] args) =>

await new CliApplicationBuilder()

.AddCommandsFromThisAssembly()

.Build()

.RunAsync(args);

}In order to add functionality to your application you need to define commands. Commands are essentially entry points for the user to interact with your application. You can think of them as something similar to controllers in ASP.NET Core applications.

In CliFx you define a command by making a new class that implements ICommand and annotating it with CommandAttribute. To specify properties that will be set from command line you need to annotate them with CommandOptionAttribute.

Here's an example command that calculates logarithm. It has a name ("log") which the user needs to specify in order to invoke it. It also contains two options, the source value ("value"/'v') and logarithm base ("base"/'b').

[Command("log", Description = "Calculate the logarithm of a value.")]

public class LogCommand : ICommand

{

[CommandOption("value", 'v', IsRequired = true, Description = "Value whose logarithm is to be found.")]

public double Value { get; set; }

[CommandOption("base", 'b', Description = "Logarithm base.")]

public double Base { get; set; } = 10;

public ValueTask ExecuteAsync(IConsole console)

{

var result = Math.Log(Value, Base);

console.Output.WriteLine(result);

return default;

}

}By implementing ICommand this class also provides ExecuteAsync method. This is the method that gets called when the user invokes the command. Its return type is ValueTask in order to facilitate both synchronous and asynchronous execution. If your command always runs synchronously, simply return default at the end of the method.

The ExecuteAsync method also takes an instance of IConsole as a parameter. You should use the console parameter in places where you would normally use System.Console, in order to make your command testable.

Finally, the command defined above can be executed from the command line in one of the following ways:

myapp log -v 1000myapp log --value 8 --base 2myapp log -v 81 -b 3

When resolving options, CliFx can convert string values obtained from the command line to any of the following types:

- Standard types

- Primitive types (

int,bool,double,ulong,char, etc) - Date and time types (

DateTime,DateTimeOffset,TimeSpan) - Enum types

- Primitive types (

- String-initializable types

- Types with constructor that accepts a single

stringparameter (FileInfo,DirectoryInfo, etc) - Types with static method

Parsethat accepts a singlestringparameter and anIFormatProviderparameter - Types with static method

Parsethat accepts a singlestringparameter

- Types with constructor that accepts a single

- Nullable versions of all above types (

decimal?,TimeSpan?, etc) - Collections of all above types

- Array types (

T[]) - Types that are assignable from arrays (

IReadOnlyList<T>,ICollection<T>, etc) - Types with constructor that accepts a single

T[]parameter (HashSet<T>,List<T>, etc)

- Array types (

If you want to define an option of your own type, the easiest way to do it is to make sure that your type is string-initializable, as explained above.

It is also possible to configure the application to use your own converter, by calling UseCommandOptionInputConverter method on CliApplicationBuilder.

var app = new CliApplicationBuilder()

.AddCommandsFromThisAssembly()

.UseCommandOptionInputConverter(new MyConverter())

.Build();The converter class must implement ICommandOptionInputConverter but you can also derive from CommandOptionInputConverter to extend the default behavior.

public class MyConverter : CommandOptionInputConverter

{

protected override object ConvertValue(string value, Type targetType)

{

// Custom conversion for MyType

if (targetType == typeof(MyType))

{

// ...

}

// Default behavior for other types

return base.ConvertValue(value, targetType);

}

}You may have noticed that commands in CliFx don't return exit codes. This is by design as exit codes are considered a higher-level concern and thus handled by CliApplication, not by individual commands.

Commands can report execution failure simply by throwing exceptions just like any other C# code. When an exception is thrown, CliApplication will catch it, print the error, and return an appropriate exit code to the calling process.

If you want to communicate a specific error through exit code, you can throw an instance of CommandException which takes exit code as a constructor parameter.

[Command]

public class DivideCommand : ICommand

{

[CommandOption("dividend", IsRequired = true)]

public double Dividend { get; set; }

[CommandOption("divisor", IsRequired = true)]

public double Divisor { get; set; }

public ValueTask ExecuteAsync(IConsole console)

{

if (Math.Abs(Divisor) < double.Epsilon)

{

// This will print the error and set exit code to 1337

throw new CommandException("Division by zero is not supported.", 1337);

}

var result = Dividend / Divisor;

console.Output.WriteLine(result);

return default;

}

}In a more complex application you may need to build a hierarchy of commands. CliFx takes the approach of resolving hierarchy at runtime based on command names, so you don't have to specify any parent-child relationships explicitly.

If you have a command "cmd" and you want to define commands "sub1" and "sub2" as its children, simply name them accordingly.

[Command("cmd")]

public class ParentCommand : ICommand

{

// ...

}

[Command("cmd sub1")]

public class FirstSubCommand : ICommand

{

// ...

}

[Command("cmd sub2")]

public class SecondSubCommand : ICommand

{

// ...

}It is possible to gracefully cancel execution of a command and preform any necessary cleanup. By default an app gets forcefully killed when it receives an interrupt signal (Ctrl+C or Ctrl+Break). You can call console.GetCancellationToken() to override the default behavior and get CancellationToken that represents the first interrupt signal. Second interrupt signal terminates an app immediately. Note that the code that executes before the first call to GetCancellationToken will not be cancellation aware.

You can pass CancellationToken around and check its state.

Cancelled or terminated app returns non-zero exit code.

[Command("cancel")]

public class CancellableCommand : ICommand

{

public async ValueTask ExecuteAsync(IConsole console)

{

console.Output.WriteLine("Printed");

// Long-running cancellable operation that throws when canceled

await Task.Delay(Timeout.InfiniteTimeSpan, console.GetCancellationToken());

console.Output.WriteLine("Never printed");

}

}CliFx uses an implementation of ICommandFactory to initialize commands and by default it only works with types that have parameterless constructors.

In real-life scenarios your commands will most likely have dependencies that need to be injected. CliFx doesn't come with its own dependency container but instead it makes it really easy to integrate any 3rd party dependency container of your choice.

For example, here is how you would configure your application to use Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection (aka the built-in dependency container in ASP.NET Core).

public static class Program

{

public static async Task<int> Main(string[] args)

{

var services = new ServiceCollection();

// Register services

services.AddSingleton<MyService>();

// Register commands

services.AddTransient<MyCommand>();

var serviceProvider = services.BuildServiceProvider();

return await new CliApplicationBuilder()

.AddCommandsFromThisAssembly()

.UseCommandFactory(schema => (ICommand) serviceProvider.GetRequiredService(schema.Type))

.Build()

.RunAsync(args);

}

}Similar to dependency injection, CliFx offers complete flexibility when it comes to option validation.

The following example demonstrates how to add validation to commands using FluentValidation.

[Command("user add")]

public class UserAddCommand : ICommand

{

[CommandOption("name", 'n', IsRequired = true)]

public string Username { get; set; }

[CommandOption("email", 'e')]

public string Email { get; set; }

public ValueTask ExecuteAsync(IConsole console)

{

var validationResult = new UserAddCommandValidator().Validate(this);

if (!validationResult.IsValid)

throw new CommandException(validationResult.ToString());

// ...

}

}public class UserAddCommandValidator : AbstractValidator<UserAddCommand>

{

public UserAddCommandValidator()

{

RuleFor(u => u.Username).NotEmpty().Length(0, 255);

RuleFor(u => u.Email).EmailAddress();

}

}In most cases, your commands will be defined in your main assembly which is where CliFx will look if you initialize the application using the following code.

var app = new CliApplicationBuilder().AddCommandsFromThisAssembly().Build();If you want to configure your application to resolve specific commands or commands from another assembly you can use AddCommand and AddCommandsFrom methods for that.

var app = new CliApplicationBuilder()

.AddCommand(typeof(CommandA)) // include CommandA specifically

.AddCommand(typeof(CommandB)) // include CommandB specifically

.AddCommandsFrom(typeof(CommandC).Assembly) // include all commands from assembly that contains CommandC

.Build();CliFx comes with a simple utility for reporting progress to the console, ProgressTicker, which renders progress in-place on every tick.

It implements a well-known IProgress<double> interface so you can pass it to methods that are aware of this abstraction.

To avoid polluting output when it's not bound to a console, ProgressTicker will simply no-op if stdout is redirected.

var progressTicker = console.CreateProgressTicker();

for (var i = 0.0; i <= 1; i += 0.01)

progressTicker.Report(i);CliFx makes it really easy to test your commands thanks to the IConsole interface.

When writing tests, you can use VirtualConsole which lets you provide your own streams in place of your application's stdin, stdout and stderr. It has multiple constructor overloads allowing you to specify the exact set of streams that you want. Streams that are not provided are replaced with stubs, i.e. VirtualConsole doesn't leak to System.Console in any way.

Let's assume you want to test a simple command such as this one.

[Command]

public class ConcatCommand : ICommand

{

[CommandOption("left")]

public string Left { get; set; } = "Hello";

[CommandOption("right")]

public string Right { get; set; } = "world";

public ValueTask ExecuteAsync(IConsole console)

{

console.Output.Write(Left);

console.Output.Write(' ');

console.Output.Write(Right);

return default;

}

}By substituting IConsole you can write your test cases like this.

[Test]

public async Task ConcatCommand_Test()

{

// Arrange

using (var stdout = new StringWriter())

{

var console = new VirtualConsole(stdout);

var command = new ConcatCommand

{

Left = "foo",

Right = "bar"

};

// Act

await command.ExecuteAsync(console);

// Assert

Assert.That(stdout.ToString(), Is.EqualTo("foo bar"));

}

}And if you want, you can even test the whole application in a similar fashion.

[Test]

public async Task ConcatCommand_Test()

{

// Arrange

using (var stdout = new StringWriter())

{

var console = new VirtualConsole(stdout);

var app = new CliApplicationBuilder()

.AddCommand(typeof(ConcatCommand))

.UseConsole(console)

.Build();

var args = new[] {"--left", "foo", "--right", "bar"};

// Act

await app.RunAsync(args);

// Assert

Assert.That(stdout.ToString(), Is.EqualTo("foo bar"));

}

}When troubleshooting issues, you may find it useful to run your app in debug or preview mode. To do it, simply pass the corresponding directive to your app along with other command line arguments, e.g.: myapp [debug] user add -n "John Doe" -e john.doe@example.com

If your application is ran in debug mode ([debug] directive), it will wait for debugger to be attached before proceeding. This is useful for debugging apps that were ran outside of your IDE.

If preview mode is specified ([preview] directive), the app will print consumed command line arguments as they were parsed. This is useful when troubleshooting issues related to option parsing.

You can also disallow these directives, e.g. when running in production, by calling AllowDebugMode and AllowPreviewMode methods on CliApplicationBuilder.

var app = new CliApplicationBuilder()

.AddCommandsFromThisAssembly()

.AllowDebugMode(true) // allow debug mode

.AllowPreviewMode(false) // disallow preview mode

.Build();Here's how CliFx's execution overhead compares to that of other libraries.

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.11.5, OS=Windows 10.0.14393.3144 (1607/AnniversaryUpdate/Redstone1)

Intel Core i5-4460 CPU 3.20GHz (Haswell), 1 CPU, 4 logical and 4 physical cores

Frequency=3125011 Hz, Resolution=319.9989 ns, Timer=TSC

.NET Core SDK=2.2.401

[Host] : .NET Core 2.2.6 (CoreCLR 4.6.27817.03, CoreFX 4.6.27818.02), 64bit RyuJIT

Core : .NET Core 2.2.6 (CoreCLR 4.6.27817.03, CoreFX 4.6.27818.02), 64bit RyuJIT

Job=Core Runtime=Core| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Ratio | RatioSD | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CliFx | 31.29 us | 0.6147 us | 0.7774 us | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2 |

| System.CommandLine | 184.44 us | 3.4993 us | 4.0297 us | 5.90 | 0.21 | 4 |

| McMaster.Extensions.CommandLineUtils | 165.50 us | 1.4805 us | 1.3124 us | 5.33 | 0.13 | 3 |

| CommandLineParser | 26.65 us | 0.5530 us | 0.5679 us | 0.85 | 0.03 | 1 |

| PowerArgs | 405.44 us | 7.7133 us | 9.1821 us | 12.96 | 0.47 | 6 |

| Clipr | 220.82 us | 4.4567 us | 4.9536 us | 7.06 | 0.25 | 5 |

Given that there are probably a dozen libraries that help with building CLI applications, I wanted to add this section to explain how is CliFx any different and what are the driving vectors for its design.

-

Application framework. CliFx is not a command line parser, CliFx is an application framework. It takes care of the whole input layer so that you may as well forget you're writing a command line application. While a regular console application has one entry point, the

Main()method, in CliFx each command is a separate entry point, elevating the abstraction one level higher. -

Declarative setup. CliFx makes it easier to think of your CLI more as a class library than an application. As a library it has an API defined in a form of classes and properties, so there shouldn't be any reason to have to redefine everything again in a different form. Attributes work really well here because they are concise and are placed right next to the types/members they annotate, eliminating additional cognitive load and unnecessary boilerplate code.

-

Command separation. CliFx follows "one class per command" principle, as opposed to having different commands defined as methods of the same class. This is important for segregation of concerns but also makes sense because commands often have different dependencies. When defining options, you also have a lot more freedom when they are properties rather than method parameters.

-

Command contract. CliFx enforces a contract on all commands to make them consistent and to reduce runtime-validated rules. Instead of having to look up the signature of the entry point method, you can simply generate a stub from the interface and build from there.

-

Async-first. CliFx commands are asynchronous by default to facilitate execution of both synchronous and asynchronous code. In the modern era of programming, it would be a disaster if asynchronous commands weren't supported.

-

Implicit exit codes. CliFx moves the concern of dealing with exit codes from command level to the application level. When writing commands, you don't have to bother with printing errors and returning exit codes, just throw an appropriate exception and CliFx will take care of everything on its own.

-

Testability. CliFx commands and applications are designed to be easily testable. One major downside of most other frameworks is that it's really hard to test how commands interact with the console.

-

Pretty help text. CliFx emphasizes the importance of good user interface by rendering help text using multiple colors. It's a mystery why nobody bothers making the help text more appealing, it's almost as if nobody cares about the end user.

CliFx is made out of "Cli" for "Command Line Interface" and "Fx" for "Framework". It's pronounced as "cliff ex".