Currently under construction. Read at your own risk!!

Since forever ago, I’ve wanted to try writing assembly, even if just to understand why the Rollercoaster Tycoon creator would write 99% of the game in it.

Embarking on this quest, I quickly found a lot of scattered and difficult to understand resources. It took compiling a bunch of different materials together to come to a high level understanding of what’s happening in my computer.

I wanted to write down my learnings and make an approachable guide for people who are new to this part of their system (like me!), including working code examples. Enjoy!

- RISC-V

- X86-64 Intel Syntax

- C (For comparison purposes)

This may sound counterintuitive, but computers are actually quite simple. I know you may be shaking your head, insisting that my statement can't possibly be true, but I promise you that literally everything your computer is doing can be represented with just two values: 0 and 1.

Now here's the catch - I said they're fundamentally simple, but I didn't say they're always easy to understand. Even though computers are, at their core, doing fairly simple tasks, they can be seriously confusing to learn about! We have to remember that computers have been built up layer by layer over a long period of time. These layers have produced the amazing, efficient, incredible machines that we use today. But, these layers also make learning about computers feel like a serious nightmare sometimes, because there's just so much to learn about.

Now, I will say that communicating with your CPU directly is generally quite unnecessary, as we now have higher level languages that are fast enough for most of our needs. That being said, the game RollerCoaster Tycoon is written 99% in assembly language. Not only that, but if you're writing operating systems, doing game engine development, or working on other low level systems, you're sometimes writing assembly directly because you need things to be lightning fast.

Even though you or I may never need to write assembly, I think that building an understanding of how your computer works at this level can be pretty dang empowering, and can help you appreciate all of the other stuff you do on your computer. In fact, the minute I wrote another program after writing in assembly, I was so happy it wasn't assembly. Sorry assembly, I still love you!

I hope this guide helps you to demystify some of the lowest layers, and hopefully turn it from something that feels like magic to something that feels graspable. I personally didn’t know how these things worked before I started writing this guide, so I hope this helps you learn the things I’ve pieced together on my journey to understanding my computer better.

Alright, let's get to the good stuff. Like, what even is a CPU?

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

Have you heard of the companies Intel or AMD? These are two popular companies that manufacture the CPUs that go into our computers. All of the computers we use contain something called a central processing unit, also known as the CPU or the processor, which effectively acts as the brain of the computer.

Computers contain other processing units (like the graphics card!) that are responsible for processing other more specific things, but the CPU is your general powerhouse for all computing tasks. That being said, the CPU can do shockingly little: it can read values, set values, and perform simple math calculations like addition and subtraction.

You hand it numbers, and it’s put to work crunching the data however you’d like. That's it. Everything your computer doing is made up of just that. Isn't that wild?

One way we can communicate with the CPU is by writing instructions for it in a format called assembly language. Assembly language is the lowest level of abstraction in computers where the code you write is still human readable. You may disagree about the human readable part when you first see it, but I promise you it's better than what the computer is looking at!

What do we mean by an abstraction? Well, an abstraction is a layer above something else that makes that thing easier to do.

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

For example, let's take a steering wheel. A steering wheel makes driving simple - you just turn left and right, and the amount you turn maps to how much your tires turn. But, what’s happening underneath? The steering wheel is an abstraction layer on top of rods, levers, and whatever else is happening inside that car, simplifying the act of turning for you. Or something like that. I clearly don't know anything about cars.

In our case, assembly is the steering wheel, and the rods, levers, and other hidden stuff is our machine code.

Here's the thing about computers. They can actually only understand numbers. So, machine code is just a bunch of numbers that the CPU reads to figure out what instructions to execute and on what data. It's the computer-readable code.

Since we humans like to read text, assembly is a text based language, consisting of acronyms that represent instructions to the computer. Alas, since they are text, they are not directly readable by the CPU. So that text file gets translated, through something called the assembler, into the numbers that the computer can then read.

It’s like if you were an American and you were giving your Icelandic friend a cake recipe. Americans write recipes in imperial measurements (eg cups, tablespoons, etc.), and Icelandic people write recipes in metric measurements (grams, liters, etc.).

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

Line by line you’d translate the recipe until you have a new recipe for your friend to use. You’d take the first measurement, 2 cups of flour (assembly language), convert it to grams (the assembler), and then write the converted recipe to use 68 grams of flour (machine code). Look at you go - you’re the assembler here!

You could skip all of this assembly shenanigans by writing the machine code directly, but machine code looks something like this in binary (we will talk about what binary is a little bit later):

01000111 00000000 11110010 10101110 11110010 00000001 11000011 11100010 00001011

Assembly, on the other hand, looks something like:

mov r12, r13

add r12, 4I know this doesn’t look extremely friendly, especially compared to the high level programming languages we have today. However, I promise you it is far friendlier than just writing a bunch of numbers!

All programming languages are some level of abstraction above machine code. But, in the end, all human written code has to be converted into numbers for your CPU to be able to read. Your CPU is able to read these numbers with the help of something called a decoder.

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

A decoder is a specialized device on the CPU that takes input and decodes what it’s trying to do. These tasks are represented as our assembly instructions.

A CPU has a mapping from number to instruction, something like:

| Number | Instruction |

|---|---|

| 1 | add |

| 2 | sub |

| ... | ... |

The decoder grabs the next instruction to execute, which looks like a bunch of numbers. It looks at the first number, and let's say it sees the number 2. The decoder is then able to map the number 2 to the subtraction instruction. So now the decoder can send the data along to the right places to do the subtraction.

How does the decoder know how to decode these things? It’s actually built physically into the chip itself, where the circuitry determines the instruction set.

You may be wondering what this might look like. If you are, you’re in luck! Let’s map our last add line to machine code. This is a completely fictional example, but it's a demonstration of how the computer decodes the numbers.

In order to explain this, let's briefly talk about registers. We will get into this more later, but for this example, they're places where you can store numbers temporarily.

add r12, 4; Add 4 to the number saved in register 12In machine code, this may end up looking like this in binary (we will cover binary later), or base 2:

00000001 00001100 00001100 00000100

Which, in base 10 (how we normally talk about numbers!), is:

1 12 4

The decoder would see the first 1, and it would know that the first number it receives should map to an instruction. Let's say instruction 1 is add.

The decoder knows that the add instruction's first argument is both:

- the save destination

- and the location of the first number to add

The decoder then sees that the next byte has the value 12, so it knows that its save destination is register 12 (r12). It can then grab the number stored in r12 for the math part.

The decoder knows that next comes the argument for the number to add. It sees 4, then adds 4 to whatever is in r12, and saves that new value to r12. Voila, maths!

Now we know how the CPU is able to interpret machine code, which is just numbers, as instructions. And we know that these instructions can be represented with just 1s and 0s, also known as binary.

In the physical world, these binary numbers map to electrical circuits. To simplify a bit, if a circuit contains electrical current, it can be considered "on", or 1. If it doesn't have electrical current, it can be considered "off", or 0. Using this principal, multiple circuits can be arranged in a group to represent binary numbers.

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

Imagine a warehouse where we are packing boxes. In this metaphor, the warehouse is your CPU, and a box is a grouping of electrical signals. A single box will travel through the warehouse on conveyor belts in order to make it from one working station to another. The conveyor belts, in the CPU world, are known as buses. Buses are effectively just wires that allow electricity to travel from one place to another, and there are different types of wires depending on what kind of data you want to send around.

As a box travels around the warehouse on conveyor belts, it will be stopped at different working stations. Some stations may check inside the box and send it elsewhere based on what it finds. Other stations may add or remove stuff to or from the box. This is just like in a CPU: our data, or electrical signals, travel around the CPU on buses, and when it reaches different parts of the CPU, it may have its value checked or modified.

In our warehouse, we want to make sure everything happens at an organized pace, and there aren't any backups at stations. One way we can accomplish this is by setting everything to a timer. Let's say our boxes move forward at the pace of 1 station per second, and each station takes 1 second to perform its task. Back in CPU land, this would be our processor clock.

It's not a clock that would be useful for you or me, but is made of material that oscillates at a certain frequency, giving you a bunch of vibrations per second. These vibrations help the processor keep track of time.

This clock is going fast. You're seeing something like one vibration every microsecond, which is about 1000000 vibrations per second. We call each one of these vibrations a "clock tick". These are important for us because for every clock tick, the CPU reads one instruction.

You may have heard the term “memory” thrown around when talking about computers. Usually when people use that term, they’re referring to random access memory, or RAM, which is a type of short term storage your computer has.

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

Accessing your RAM is kind of like going to the post office. Each piece of data (mail, in our metaphor) has an "address" (mailbox number) where you can view the contents (mail). You can also clear out the contents (take the mail out of the box), and then store new pieces of data (get new pieces of mail).

Our pieces of mail are actually just electrical currents. Because we store data as electricity, when your computer turns off and no more electricity is traveling to it, all of the things you have stored get cleared out! It’s kind of like if every night when your post office closed, all of the mail was thrown out. That’s why we refer to it as short term memory - we want to make sure to store important things in the hard drive, which is our longer term storage, lest it be thrown away.

Our RAM, or post office, has quite a bit of room to store our things - enough to hold entire packages. But, visiting the post office and carrying mail around can be slow and cumbersome. So, for faster (but smaller) storage, we have a set of tiny mailboxes outside the post office that can just hold letters. Those are our registers.

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

Registers are where the CPU can store small pieces of data so that it can keep interacting with them. For example, let’s say we need to add two numbers together. First, the CPU retrieves the first number it needs for the equation. Since the CPU can really only do one thing at a time, it needs to put this number down in order to grab the next number. So it stores this first number into a register for the time being. Next, the CPU grabs the second number in the equation. The CPU now has all the information it needs to add the two numbers together. It goes ahead and executes the adding instruction, passing that new number along, and then moves on to the next instruction it’s given.

Depending on the processor, you may get around 16 general purpose registers to store your data in. There are more registers than that, but some registers are used internally and can’t be directly accessed.

Now you may be asking yourself - why don’t we store everything in the registers, since memory is slower? Well, we only have a limited amount of space in our registers. The actual size depends on your computers hardware, but RAM can easily hold over 15 million times the amount that registers can! Since computers have to process so much data, we can very quickly run out of space in our registers. So any data that we need to hold onto for a bit while we calculate other things, we throw into RAM.

There are many different assembly languages, depending on the processor you want to talk to.

- X86 is one of the most useful assembly languages, but is also one of the hardest to write. It's used for Intel processors, which have to process a lot of data!

- ARM is also useful but difficult, used for the new Apple M1 processors

- 6502 was used for older gaming systems (Atari and NES, for example), but is still used in small devices today

- Z80 is another one you might know - remember those TI-8X calculators you may have used in school? Well, to program those, you'd use the Z80 assembly language!

- RISC-V is a simpler assembly language, made for educational and research purposes

Given that the processor on my MacBook Pro is an Intel X86-64, I will be using X86 assembly code to demonstrate assembly concepts. Yes, I know, my computer is old. Sorry.

NOTE: Fill this in about bits vs bytes etc

In order to talk about assembly, we need to dig a bit more into what registers are. Like we talked about in the saving data section, registers are available for short term data storage on the CPU.

just a placeholder image to break up the content!

Note: These examples are written in X86-64 Intel syntax assembly language

; Note: Anything that comes after a semicolon is considered a comment.

; A comment in code means that the compiler will ignore it, so you have

; a place to jot down notes, TODOs, etc. add rdi, 3 sub rdi, 2This is not an exhaustive list, but a list of some examples of instructions to demonstrate the kinds of conditionals assembly provides us.

A conditional is something that relies on a condition being met to execute it.

Note: Check out http://unixwiz.net/techtips/x86-jumps.html for a list of conditional jumps for X86 Intel.

jne .placeToJump jg .goHere jl .doSomeMath _main:

call .performAddition

; ret will return here and keep executing!

.performAddition:

add rdi, 3

ret ; returns back to where you left off in _main!WRITING NOTE: Talk about how this maps to jump/call instructions in assembly

The CPU has many specialized registers, which we don't access directly. One of them is the program counter, which keeps track of what code it's executing. This register stores the memory address of the current line of the current program it's executing, and updates itself automatically. For example, let’s say we are running an assembly program. There's an instruction for adding two numbers together. Once that instruction finishes running, the program counter increments to the memory address of the next instruction of the program.

Computers allocate a chunk of memory in the RAM to be the “stack”, a place where you can store bytes (COMMENT 🐣: would using the term data be easier to understand? readers might not completely wrap their minds around bytes yet...) for later use. You can do 2 things with a stack: push values onto it, which go on top of the previous values, and pop values off of it, which grabs from the top of the stack. Need something at the bottom? Too bad! You gotta go through the top.

The purpose of the stack is to store things for later. Now you might say, hey wait a minute, we use registers for that! And you’d be correct! However, we have a limited number of registers. Let’s say we are doing some complicated math, and we need to store a few amounts away for a while while we work through a problem. We can just push those values to save on the stack, and then when we’re done with that math, we can pop them off and continue like nothing ever happened. Very convenient!

So now that we know about the stack, the stack pointer is a special register the CPU has that keeps track of where the top of the stack is. So every time we push onto the stack, it automatically increments the pointer. Every time we pop off of the stack, it automatically decrements it. This pointer is actually pointing to the address of where this value lives in memory, since we have a special area of the memory sectioned off just for our stack.

Ever heard of a stack overflow? Or perhaps stackoverflow.com? It’s named after this stack right here! You don’t need to know this for the purposes of this guide, but while we’re here, an overflow can happen for many reasons. One reason could be caused by accidentally writing an infinite loop, where we have a loop somewhere that never gets exited, and let's say that loop adds things onto the stack. Eventually, our stack runs out of room, and bam! Stack overflow error.

(COMMENT 🐣: I found this section on the stack a little hard to wrap my head around... i think an explaination and example of when a stack is used could be useful. Also, do we need to discuss other parts of the RAM like the heap? I feel like this is a little too detailed for a general overview of how the CPU works haha cuz then we might need to explain memory allocation...)

If you thought you'd get through this without doing any math, well, I'm sorry. We have to do a little bit so that we can understand what the computer is doing, because like I said, it's all just basic math underneath. Now, I promise you it won't be too hard. You may get a little confused and your brain may hurt, but just stick with me here and we'll make it through to the assembly section.

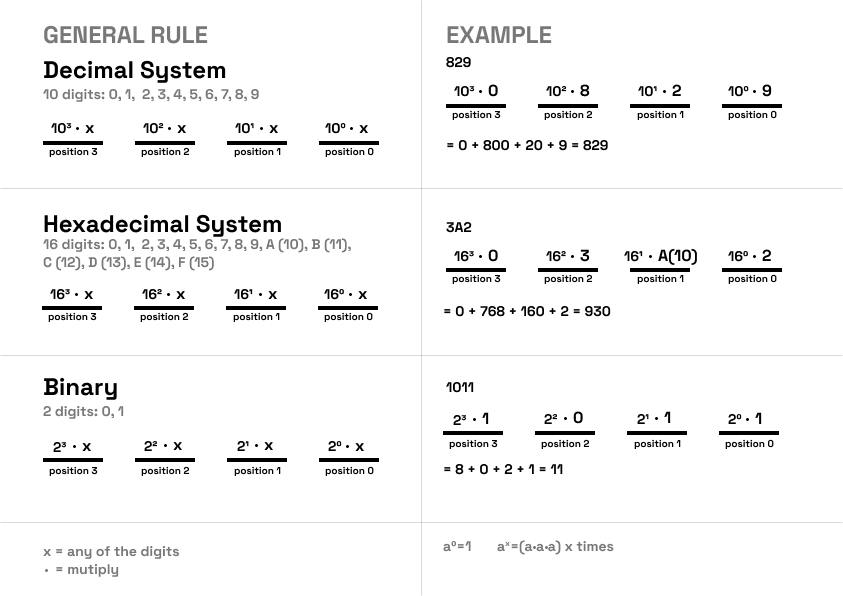

All numbers in assembly language are represented by hexadecimal Our usual numbers are base 10 so when you see 125 as a number, you can think of that as:

- (10 * 10^2) + (2 * 10^1) + (5 * 10^0)

- 100 + 20 + 5 = 125

Hex is base 16, which means is the available digits are 0-9 and A-F (for 10-15). Each digit is the value of the digit (0-15 where 10-15 are represented by A-F) times 16 to the power of the position of the digit (starting with 0 from the right).

7D would translate to:

- D = 13

- (7 * 16^1) + (13 * 16^0)

- 112 + 13 = 125

When people hear that I program for a living, they think that I stare at 0s and 1s all day. Luckily I do not, because that would give me a migraine. However, binary is important to talk about, because everything the computer is doing can be represented by these digits. These digits are referred to as binary, which is a number system that has 2 as its base.

When we think of numbers in the human world, we think of them in base 10. Base 10 means that each digit of a number can be represented with the digits 0-9. Each digit over we move (for example 1 vs 10 vs 100) is 10 times the value to the right of it (as seen in the graph above).

With binary, there are only two digits represented: 0 and 1. Each digit is the value of the digit (0 or 1) times 2 to the power of the position of the digit (starting with 0 from the right).

Boolean is a very cute word for a very simple concept! A boolean is something that can only have one of two values - true or false. True or false can also be represented as 1 for true, 0 for false.

Since we represent data in the physical world with the inclusion or absence of electrical signals, we can use something called boolean logic to determine whether a “statement” is true or false. A statement here is just boolean values, and we pass them to operations we can use depending on our use case.

Why would we ever use this? Great question! Let me let you in on a secret - everything your computer is doing is actually just composed of these logical operations. Everything. All the math your processor can do, it’s done by combining a few of these operations together. So you send it some electrical signals, it goes through a few of these “logic gates”, in the form of transistors, and BAM! You have an answer at the end. You combine a bunch of these small answers through more transistors, and then you have a larger answer!

Let’s talk through these logical operations a bit.

And is always false unless both inputs are true.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 00 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 |

| 01 | 0 |

| 11 | 1 |

OR is always false unless one of the inputs is true.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 00 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 01 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 |

NOT only requires 1 input, and it flips the input.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

NAND is always true unless both inputs are true.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 00 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 01 | 1 |

| 11 | 0 |

NOR is always false unless both inputs are false.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 00 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 |

| 01 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 |

XOR is always false unless the inputs are different.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 00 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 01 | 1 |

| 11 | 0 |

XNOR is always false unless the inputs are the same.

| In | Out |

|---|---|

| 00 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 |

| 01 | 0 |

| 11 | 1 |

Fun fact: You only need the NAND gate (AND gate followed by NOT) to do every single possible logic operation ever. That means that every possible logic circuit can be made to use only NAND! In fact, a physical NAND transistor takes up less area than an AND transistor. To make an AND, you’d actually make a NAND and then invert the output. Check out the free course From Nand2 to Tetris to build an entire computer system using just these principles.

In real circuits, you would even see amalgamations of gates (like AND+OR+NOT+OR+AND) as a single "standard cell". It’s like stacking lego bricks, but each brick is a logical operation.

Comp sci fundamentals

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?app=desktop&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtNlUrzyH5r6jN9ulIgZBpdo

- https://www.nand2tetris.org/

Boolean Logic

Number Systems

X86

- https://rderik.com/blog/let-s-write-some-assembly-code-in-macos-for-intel-x86-64/

- https://github.com/0xAX/asm

- https://web.stanford.edu/class/archive/cs/cs107/cs107.1222/guide/x86-64.html

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/X86_Assembly/X86_Architecture

- The "Getting Started Writing Assembly Language" series

- https://blog.devgenius.io/getting-started-writing-assembly-language-8ecc116f3627

- https://blog.devgenius.io/finding-an-efficient-development-cycle-for-writing-assembly-language-be2092e6db6a

- https://blog.devgenius.io/writing-an-x86-64-assembly-language-program-648b6005e8e (ESPECIALLY this one, since it had a lot of the command line arg info, although some of it works differently on mac)

- https://filippo.io/making-system-calls-from-assembly-in-mac-os-x/

- http://dustin.schultz.io/mac-os-x-64-bit-assembly-system-calls.html

- https://0xax.github.io/asm_1/

- https://github.com/0xAX/asm

- https://cs61.seas.harvard.edu/site/2018/Asm1/

- https://www.dreamincode.net/forums/topic/285550-nasm-linux-getting-command-line-parameters/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/53555298/how-to-get-arguments-from-the-command-lineassembly-nasm-ubuntu-32bit

- https://cs.lmu.edu/~ray/notes/nasmtutorial/

- https://www.figma.com/file/Uhd6Qe3lzmJ60bBQmkx7Ch/cpu

- https://gist.github.com/FiloSottile/7125822

- https://death-of-rats.github.io/posts/yasm-hello-world/

- https://dev.to/tomassirio/hello-world-in-asm-x8664-jg7

- https://jameshfisher.com/2018/03/10/linux-assembly-hello-world/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/52830484/nasm-cant-link-object-file-with-ld-on-macos-mojave

Debugger

6502

- https://skilldrick.github.io/easy6502/

- https://www.nesdev.com/6502guid.txt

- https://people.cs.umass.edu/~verts/cmpsci201/cmpsci201.html

- https://www.masswerk.at/6502/6502_instruction_set.html

- https://www.masswerk.at/6502/

- http://6502.org/tutorials/

Z80

RISC-V

- https://medium.com/swlh/risc-v-assembly-for-beginners-387c6cd02c49

- https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs3410/2019sp/riscv/interpreter/

- https://github.com/jameslzhu/riscv-card/blob/master/riscv-card.pdf

- https://github.com/riscv/riscv-isa-manual/releases/download/Ratified-IMAFDQC/riscv-spec-20191213.pdf

Misc