As any Software Engineer, I recently lost to my urge to build an HTTP server from scratch. Honestly, this is the perfect chance for me to start writing about technical stuff. Since you're already here, how about joining me? Come on, grab a drink, I'll be waiting : D

Ok. Here's how we're doing this. We're taking a top-down approach. We'll start with 1 line of code then try to get as close to "scratch" as we can. We'll do that by replacing the layers of abstraction (out-of-the-box code) with our custom code. While doing that, we will be discussing some theory.

Oh, and BTW, We'll be using Python (please don't kill me in my sleep, I put "scratch" in double quotes, I promise it'll be fun!)

- Berkeley sockets

- TCP connections

- HTTP Protocol

- Web servers

- Parsing and sending HTTP Messages

- We're working with HTTP/1.1.

- No caching: The server won't handle caching.

- No HTTPS: The server won't handle encryption.

- One connection at a time: The server won't handle concurrent connections.

- Only short-lived connections: The server will end the connection once the files are transferred.

- Only HEAD and GET requests: The server only serves static files as-is.

- HTTP server with one line of code: Using

http.server - Removing a layer of abstraction: Using

http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandlerandsocketserver.TCPServer - Writing our custom TCP server (

PicoTCPServer): Replacingsocketserver.TCPServer - Writing our custom HTTP handler (

PicoHTTPRequestHandler): Replacinghttp.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler - The finale!

Python has a standard library that we can use to create a server out-of-the-box: http. So, to create an HTTP server with it, simply run this command:

$ python -m http.server 8000 # i know, this isn't python code, shut up >:-(

# Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 8000 (http://0.0.0.0:8000/) ...Now if you want to know what this does you can read this (maybe after you finish this article cause we'll be talking about how that code works in a minute).

Removing a layer of abstraction: Using http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler and socketserver.TCPServer

Ok, we can officially start with this: (please take a a quick look at the code :3 )

#! /usr/bin/env python3

import http.server

import socketserver

import logging

# ===== Logging =====

logging.basicConfig(

level=logging.INFO

)

logger = logging.getLogger(

'http-server'

)

# ===== Logic =======

handler = http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler

with socketserver.TCPServer(('0.0.0.0', 8000), handler) as http:

logger.info(f'Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 8000')

http.serve_forever()I think you may already have gotten an idea about what that code is doing. It can be boiled down to 3 lines:

handler = http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandlerwith socketserver.TCPServer(('0.0.0.0', 8000), handler) as http:http.serve_forever()

So from the looks of it, we have something that "handles" the request (SimpleHTTPRequestHandler), a TCP server (TCPServer) that's listening on 0.0.0.0:8000, and that TCP server is running for ever (.serve_forever()).

Let's keep that in mind and take a quick tangent to talk about the HTTP request lifecycle.

We always talk about HTTP and the client-server architecture. So, how does the request travel from the client to the server and from the server to the client? The answer is Berkeley Sockets (AKA: BSD Sockets, POSIX Sockets, Internet Socket).

A Network Socket is a 2-way communication channel or an endpoint for sending and receiving data in a network.

Those sockets come in different flavors. We're interested in the TCP ones. The HTTP protocol relies on TCP sockets because they're built to be:

- Reliable, as in no packet drops -- TCP detects and re-transmits dropped packets.

- Orderly delivered. So what is sent is what is received in the exact order.

Now back to the Berkeley Sockets.

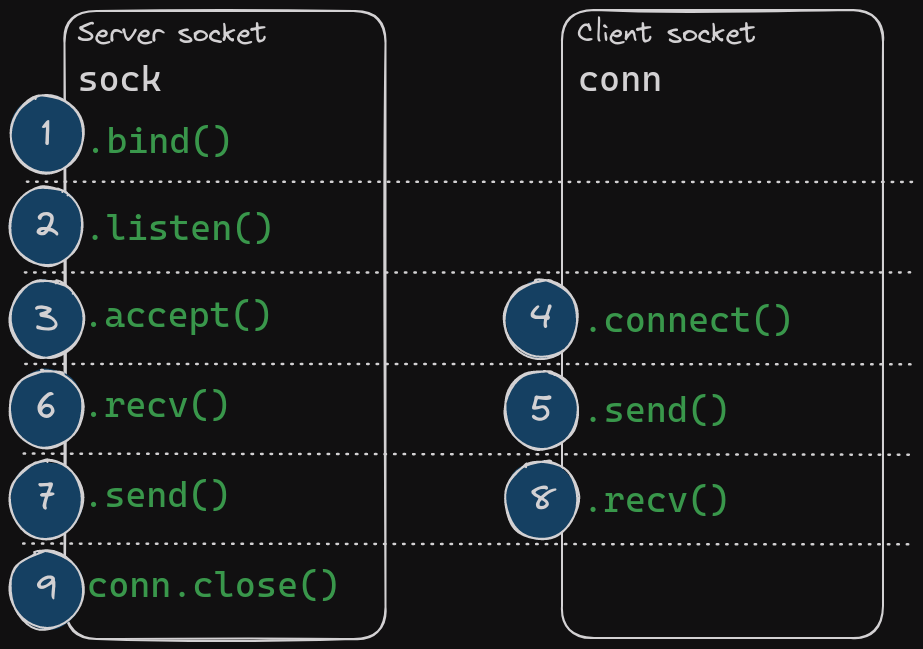

Berkeley Socket is an API for Network Socket. Let's take a quick look at how they operate in the client-server architecture:

- The server socket will be created, and bidden to a port.

- The server socket will then be in the listening state. Any incoming connections at this point will be placed in something called the "accept queue". Those connections will be waiting to be accepted by the server socket.

- The server will accept the connection.

.accept()awaits for connections. It will return a new socket instance that will be used by the server to communicate with the client. - A client socket will be created, it will connect to the server socket. (A 3-way handshake will be initiated on

.connect()). - The client sends a request.

- The server reads the request.

- The server sends back the response.

- The client receives the response.

- The server closes the connection.

Side note: Berkeley Sockets are designed to be concurrent. A server socket or a listening socket can accept multiple client sockets.

.listen()takes an argument calledbacklogwhich is the maximum number of connection in the accepted queue. Connections that come after that limit is reached will be refused.

To make sure we're familiar with how sockets communicate we'll create a simple server-client arch in which the server echos messages sent by the client:

# server.py

import socket

HOST = '127.0.0.1'

PORT = 6666

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

print(f'Listening on {HOST}:{PORT}')

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

print(f'Connected to {addr}')

while True:

data = conn.recv(1024)

print(f'Received {data}')

if not data:

break

conn.sendall(data)# client.py

import socket

HOST = '127.0.0.1'

PORT = 6666

MESSAGE = b'Hello, world'

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect((HOST, PORT))

s.sendall(MESSAGE)

received_message = s.recv(len(MESSAGE))

print(received_message.decode())You don't have to understand every line for now, you can copy/paste the code and run it just to get your hands dirty for what's coming.

Now that we're familiar with how sockets communicate, we can start writing our own TCP server! We'll call it PicoTCPServer (The pico is because it's insultingly basic compared to other TCP servers).

Anyways, we need something that:

- Takes a socket address (IP address and port number pair) and an HTTP handler (

SimpleHTTPRequestHandler) as arguments. - Creates a listening socket on the given socket address and accepts connections from clients (e.g. browser).

- Serves the response and closes the connection to the client.

...

class PicoTCPServer:

def __init__(

self,

socket_address: tuple[str, int],

request_handler: PicoHTTPRequestHandler

) -> None:

self.request_handler = request_handler

self.sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

self.sock.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

self.sock.bind(socket_address)

self.sock.listen()

def serve_forever(self) -> None:

while True:

conn, addr = self.sock.accept()

with conn:

logger.info(f'Accepted connection from {addr}')

request_stream = conn.makefile('rb')

response_stream = conn.makefile('wb')

self.request_handler(

request_stream=request_stream,

response_stream=response_stream

)

logger.info(f'Closed connection from {addr}')

def __enter__(self) -> PicoTCPServer:

return self

def __exit__(self, *args) -> None:

self.sock.close()

...__init__():socket.socketcreates a TCP socket (socket.SOCK_STREAM) using the IPv4 address family (sock.AF_INET).- We set the

SO_REUSEADDRflag toTruebefore binding the socket (to allow re-binding on the same socket address after connection closes -- otherwise we get anOSError: Address already in use.error). - We bind the socket to the

socket_addressthen listen to incoming connections.

serve_forever():- We accept incoming connections and serve the response using

SimpleHTTPRequestHander(request_handler()) conn.makefile('rb')creates a file-like object so we can read the bytes sent from the client socket as if we're reading data from a file (this is similar tosocket.recv()).conn.makefile('wb')creates a file-like object but this time for writing the response to the client socket (similar tosocket.send())

- We accept incoming connections and serve the response using

__enter__()and__exit__()are a syntactic sugar for python to use thewithcontext manager. When we enter thewithblock,PicoTCPServeris instantiated. When we leave it,__exit__()is called to close the server socket we created.

SO_REUSEADDR: Indicates that the rules used in validating addresses supplied in a bind(2) call should allow reuse of local addresses. For AF_INET sockets this means that a socket may bind, except when there is an active listening socket bound to the address. When the listening socket is bound to INADDR_ANY with a specific port then it is not possible to bind to this port for any local address. Argument is an integer boolean flag.

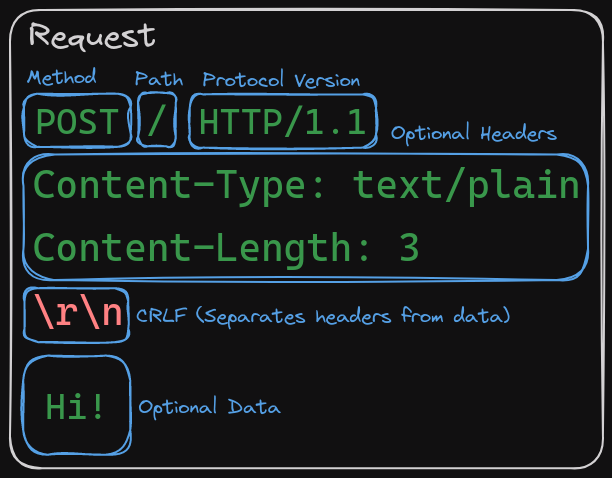

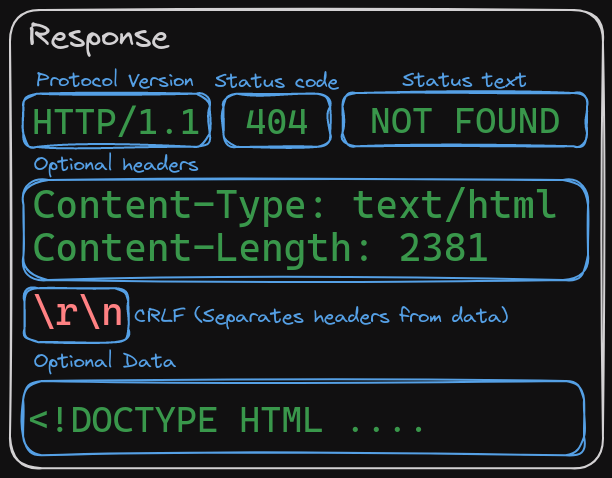

At the TCP level, to our server, there's no "request". It's just a bunch of bytes being transmitted. Those bytes encoded and may be encrypted. So we may have to decrypt it and decode it to get our beautiful HTTP request plain text:

HTTP/1.1 404 NOT FOUND

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 3124

<! DOCTYPE html ...

But since we're not doing any encryption or encoding here, we can assume that we get plain-text bytes.

Writing our custom HTTP handler (PicoHTTPRequestHandler): Replacing http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler

Alright, the first step is done. We have our plain-text HTTP request. You may have noticed we skipped talking about something while writing PicoTCPServer: The HTTP handler. We used http.server which provided us with something working right out of the box called SimpleHTTPRequestHandler.

The HTTP handler's responsibility is to parse the HTTP request and serve the appropriate response. The HTTP request is parsed according to the HTTP standards, and so is the served response.

So let's start with a skeleton:

class PicoHTTPRequestHandler:

'''

Serves static files as-is. Only supports GET and HEAD.

POST returns 403 FORBIDDEN. Other commands return 405 METHOD NOT ALLOWED.

Supports HTTP/1.1.

'''

def __init__(

self,

request_stream: io.BufferedIOBase,

client_address: tuple[str, int],

client: socket.socket,

):

pass

def handle(self) -> None:

pass

def handle_GET(self) -> None:

pass

def handle_HEAD(self) -> None:

passThere's a really good explanation of how that's done in SimpleHTTPRequestHandler's parent class(BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

"""HTTP request handler base class.

The following explanation of HTTP serves to guide you through the

code as well as to expose any misunderstandings I may have about

HTTP (so you don't need to read the code to figure out I'm wrong

:-).

HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) is an extensible protocol on

top of a reliable stream transport (e.g. TCP/IP). The protocol

recognizes three parts to a request:

1. One line identifying the request type and path

2. An optional set of RFC-822-style headers

3. An optional data part

The headers and data are separated by a blank line.

The first line of the request has the form

<command> <path> <version>

where <command> is a (case-sensitive) keyword such as GET or POST,

<path> is a string containing path information for the request,

and <version> should be the string "HTTP/1.0" or "HTTP/1.1".

<path> is encoded using the URL encoding scheme (using %xx to signify

the ASCII character with hex code xx).

The specification specifies that lines are separated by CRLF but

for compatibility with the widest range of clients recommends

servers also handle LF. Similarly, whitespace in the request line

is treated sensibly (allowing multiple spaces between components

and allowing trailing whitespace).

Similarly, for output, lines ought to be separated by CRLF pairs

but most clients grok LF characters just fine.

If the first line of the request has the form

<command> <path>

(i.e. <version> is left out) then this is assumed to be an HTTP

0.9 request; this form has no optional headers and data part and

the reply consists of just the data.

The reply form of the HTTP 1.x protocol again has three parts:

1. One line giving the response code

2. An optional set of RFC-822-style headers

3. The data

Again, the headers and data are separated by a blank line.

The response code line has the form

<version> <responsecode> <responsestring>

where <version> is the protocol version ("HTTP/1.0" or "HTTP/1.1"),

<responsecode> is a 3-digit response code indicating success or

failure of the request, and <responsestring> is an optional

human-readable string explaining what the response code means.

This server parses the request and the headers, and then calls a

function specific to the request type (<command>). Specifically,

a request SPAM will be handled by a method do_SPAM(). If no

such method exists the server sends an error response to the

client. If it exists, it is called with no arguments:

do_SPAM()

Note that the request name is case sensitive (i.e. SPAM and spam

are different requests).

...

That means the handler we will create must parse requests following that structure.

Note: The headers

Content-TypeandContent-Lengthare essential for describing the transferred data (in both the request and the response). WithoutContent-Typethe browser won't know how to render the file and will default to plain text. Without the correctContent-Lengththe browser waits indefinitely for more data (if it's more than the actual length) or reads the data partially (if it's less than the actual length).

Ok, let's update PicoHTTPHandler:

class PicoHTTPRequestHandler:

'''

Serves static files as-is. Only supports GET and HEAD.

POST returns 403 FORBIDDEN. Other commands return 405 METHOD NOT ALLOWED.

Supports HTTP/1.1.

'''

def __init__(

self,

request_stream: io.BufferedIOBase,

response_stream: io.BufferedIOBase

):

self.request_stream = request_stream

self.client = client

self.command = ''

self.path = ''

self.headers = {

'Content-Type': 'text/html',

'Content-Length': '0',

'Connection': 'close'

}

self.data = ''

self.handle()

def handle(self) -> None:

'''Handles the request.'''

# anything but GET or HEAD will return 405

# POST will return a 403

# parse the request to populate

# self.command, self.path, self.headers

self._parse_request()

...

def _parse_request(self):

# parse the request line

logger.info('Parsing request line')

requestline = self.request_stream.readline().decode()

requestline = requestline.rstrip('\r\n')

logger.info(requestline)

self.command = requestline.split(' ')[0]

self.path = requestline.split(' ')[1]

# parse the headers

headers = {}

line = self.request_stream.readline().decode()

while line not in ('\r\n', '\n', '\r', ''):

header = line.rstrip('\r\n').split(': ')

headers[header[0]] = header[1]

line = self.request_stream.readline().decode()

logger.info(headers)_parse_request() is our protagonist the the moment:

self.request_streamis the file-like socket stream that reads data from the client. Again, it's like opening a normal Python file inrbmode.self.response_steamis similar but for writing the response.- We read the first line (

requestline) and parse the command and path from it. - We then parse the headers. Remember that there's a CRLF that delimits the end of headers and the beginning of data. We parse until we find it. There's a possibility there are no optional headers in the response (

\r,'') and we handle that too. - The headers are parsed in a Python

dictfor convenience. - Since we only do HEAD and GET, we discard parsing the data.

Now after parsing the request. We need to validate the command and the path:

Now after parsing the request. We need to validate the command and the path:

class PicoHTTPHandler:

...

def handler(self) -> None:

'''Handles the request.'''

# anything but GET or HEAD will return 405

# POST will return a 403

# parse the request to populate

# self.command, self.path, self.headers

self._parse_request()

if not self._validate_path():

return self._return_404()

if self.command == 'POST':

return self._return_403()

if self.command not in ('GET', 'HEAD'):

return self._return_405()

def _validate_path(self) -> bool:

'''

Validates the path. Returns True if the path is valid, False otherwise.

'''

# the path can either be a file or a directory

# if it's a directory, look for index.html

# if it's a file, serve it

self.path = os.path.join(os.getcwd(), self.path.lstrip('/'))

if os.path.isdir(self.path):

self.path = os.path.join(self.path, 'index.html')

elif os.path.isfile(self.path):

pass

if not os.path.exists(self.path):

return False

return True

def _return_404(self) -> None:

'''NOT FOUND'''

self._write_response_line(404)

self._write_headers()

def _return_405(self) -> None:

'''METHOD NOT ALLOWED'''

self._write_response_line(405)

self._write_headers()

def _return_403(self) -> None:

'''FORBIDDEN'''

self._write_response_line(403)

self._write_headers()All the eyes should be on handler()now:

- After parsing the request, we call

_validate_path()which checks if the requested file is in our server directory. If the path was a directory then we need to look for theindex.htmlfile in the directory. - If the requested file is not found we return a 404 NOT FOUND response.

- We then validate the command. 403 FORBIDDEN for POST request. 405 METHOD NOT ALLOWED for other commands. HEAD and GET are the only ones getting handled.

Ok, now we're good to write the headers and the requested file bytes:

class PicoHTTPHanlder:

...

def handler(self) -> None:

...

command = getattr(self, f'handle_{self.command}')

command()

def handle_GET(self) -> None:

'''

Writes headers and the file to the socket.

'''

self.handle_HEAD()

with open(self.path, 'rb') as f:

body = f.read()

self.response_stream.write(body)

self.response_stream.flush() # flush to send the data

def handle_HEAD(self) -> None:

'''

Writes headers to the socket.

'''

# default to 200 OK

self._write_response_line(200)

self._write_headers(

**{

'Content-Length': os.path.getsize(self.path)

}

)

self.response_stream.flush() # flush to send the response

def _write_response_line(self, status_code: int) -> None:

reponse_line = f'HTTP/1.1 {status_code} {HTTPStatus(status_code).phrase} \r\n'

logger.info(reponse_line.encode())

self.response_stream.write(reponse_line.encode())

def _write_headers(self, *args, **kwargs) -> None:

headers_copy = self.headers.copy()

headers_copy.update(**kwargs)

header_lines = '\r\n'.join(

f'{k}: {v}' for k, v in headers_copy.items()

)

logger.info(header_lines.encode())

self.response_stream.write(header_lines.encode())

# mark the end of the headers

self.response_stream.write(b'\r\n\r\n')

...handle(): callshandle_GETorhandle_HEADbased on the command.handle_HEAD():- Writes the response line

HTTP/1.1 200 OKtoself.response_stream - Writes the headers to the response stream

Content-Lengthgets set to the size of the requested file

- Flushes the written response line and headers to be sent to the client

- Writes the response line

handle_GET:- Calls

handle_HEADsince GET is HEAD with no data. - Writes the data to

self.response_streamthen flushes it.

- Calls

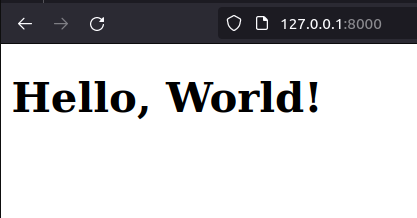

Now for a moment of truth, we will finally serve this bad boy:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Hello, World!</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

</body>

</html>Our file structure should look something like this:

|_ main.py

|_ index.htmlRunning python main.py and then opening http://127.0.0.1:8000 on browser should give us this result:

You can find the full code here: https://github.com/sakhawy/pico-server

I guess a question or two may have crossed your mind while reading this. I encourage you to mess around with the code and try to answer those questions yourself.

The server we created is very primitive and has a lot of issues:

- Handling multiple connections

- The absence of caching

- Only doing short-lived connections

- No compression/decompression

- Security concerns

- ...

The list is long! You can also read more about the protocol. MDN is a great resource for that.

Well, I hope you had fun reading this. Thanks a lot for getting to this point and have a nice day!