Welcome!

In this project I am going to build a logistic regression classifier to recognize cats.

By completion of this project, I've learn how to:

- Building the general architecture of a learning algorithm, including:

- Initializing parameters

- Calculating the cost function and its gradient

- Using an optimization algorithm (gradient descent)

- Gather all three functions above into a main model function, in the right order.

First, let's run the cell below to import all the packages that will need for this Project.

- nmpy is the fundamental package for scientific computing with Python.

- h5py is a common package to interact with a dataset that is stored on an H5 file.

- matplotlib is a famous library to plot graphs in Python.

- PIL and scipy are used here to test model with our own picture at the end.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import h5py

import scipy

from PIL import Image

from scipy import ndimage

from lr_utils import load_dataset

%matplotlib inlineI have a dataset ("train_catvnoncat.h5" and "test_catvnoncat.h5") containing: - a training set of m_train images labeled as cat (y=1) or non-cat (y=0) - a test set of m_test images labeled as cat or non-cat - each image is of shape (num_px, num_px, 3) where 3 is for the 3 channels (RGB). Thus, each image is square (height = num_px) and (width = num_px).

So, I am going to build a simple image-recognition algorithm that can correctly classify pictures as cat or non-cat.

Let's get more familiar with the dataset. Load the data by running the following code.

# Loading the data (cat/non-cat)

train_set_x_orig, train_set_y, test_set_x_orig, test_set_y, classes = load_dataset()I have added "_orig" at the end of image datasets (train and test) because I am going to preprocess them. After preprocessing, we will end up with train_set_x and test_set_x (the labels train_set_y and test_set_y don't need any preprocessing).

Each line of the train_set_x_orig and test_set_x_orig is an array representing an image. We can visualize an example by running the following code. Feel free also to change the index value and re-run to see other images.

# Example of a picture

index = 88

plt.imshow(train_set_x_orig[index])

print ("y = " + str(train_set_y[:, index]) + ", it's a '" + classes[np.squeeze(train_set_y[:, index])].decode("utf-8") + "' picture.")y = [1], it's a 'cat' picture.

Many software bugs in deep learning come from having matrix/vector dimensions that don't fit. If you can keep your matrix/vector dimensions straight you will go a long way toward eliminating many bugs.

So, I am going to find the values for:

- m_train (number of training examples)

- m_test (number of test examples)

- num_px (= height = width of a training image)

Note that train_set_x_orig is a numpy-array of shape (m_train, num_px, num_px, 3). For instance, we can access m_train by writing train_set_x_orig.shape[0].

m_train = train_set_x_orig.shape[0]

m_test = test_set_x_orig.shape[0]

num_px = train_set_x_orig.shape[1]

print ("Number of training examples: m_train = " + str(m_train))

print ("Number of testing examples: m_test = " + str(m_test))

print ("Height/Width of each image: num_px = " + str(num_px))

print ("Each image is of size: (" + str(num_px) + ", " + str(num_px) + ", 3)")

print ("train_set_x shape: " + str(train_set_x_orig.shape))

print ("train_set_y shape: " + str(train_set_y.shape))

print ("test_set_x shape: " + str(test_set_x_orig.shape))

print ("test_set_y shape: " + str(test_set_y.shape))Number of training examples: m_train = 209

Number of testing examples: m_test = 50

Height/Width of each image: num_px = 64

Each image is of size: (64, 64, 3)

train_set_x shape: (209, 64, 64, 3)

train_set_y shape: (1, 209)

test_set_x shape: (50, 64, 64, 3)

test_set_y shape: (1, 50)

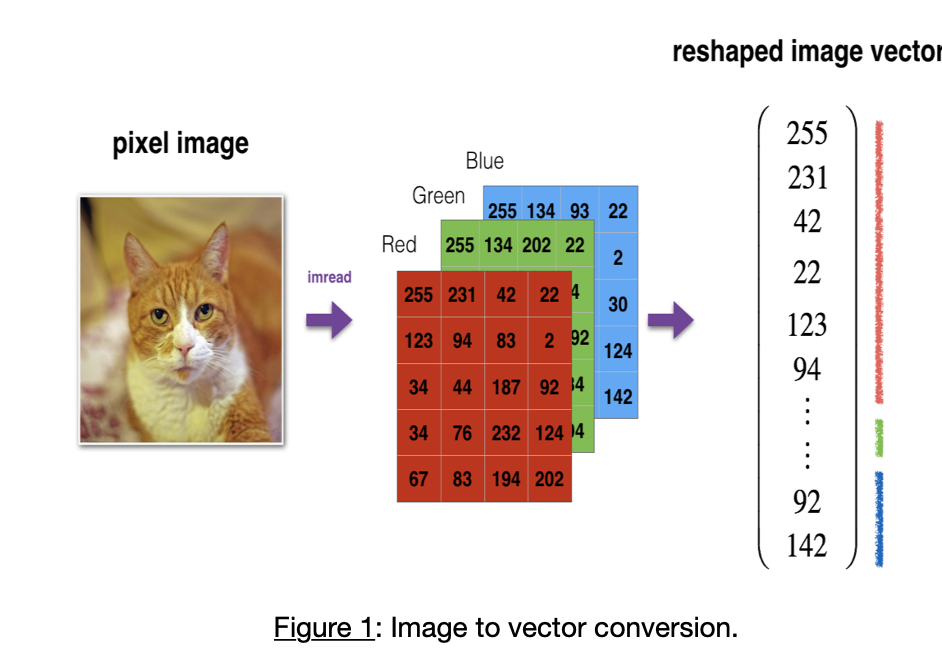

For convenience, reshape images of shape (num_px, num_px, 3) in a numpy-array of shape (num_px $$ num_px $$ 3, 1). After this, the training (and test) dataset is a numpy-array where each column represents a flattened image. There is m_train (respectively m_test) columns.

Reshaping the training and test data sets so that images of size (num_px, num_px, 3) are flattened into single vectors of shape (num_px $$ num_px $$ 3, 1).

A trick to flatten a matrix X of shape (a,b,c,d) to a matrix X_flatten of shape (b$$c$$d, a) is to use:

X_flatten = X.reshape(X.shape[0], -1).T # X.T is the transpose of X# Reshape the training and test examples

train_set_x_flatten = train_set_x_orig.reshape(train_set_x_orig.shape[0],-1).T

test_set_x_flatten = test_set_x_orig.reshape(test_set_x_orig.shape[0],-1).T

print ("train_set_x_flatten shape: " + str(train_set_x_flatten.shape))

print ("train_set_y shape: " + str(train_set_y.shape))

print ("test_set_x_flatten shape: " + str(test_set_x_flatten.shape))

print ("test_set_y shape: " + str(test_set_y.shape))

print ("sanity check after reshaping: " + str(train_set_x_flatten[0:5,0]))train_set_x_flatten shape: (12288, 209)

train_set_y shape: (1, 209)

test_set_x_flatten shape: (12288, 50)

test_set_y shape: (1, 50)

sanity check after reshaping: [17 31 56 22 33]

To represent color images, the red, green and blue channels (RGB) must be specified for each pixel, and so the pixel value is actually a vector of three numbers ranging from 0 to 255.

One common preprocessing step in machine learning is to center and standardize the dataset, meaning that substract the mean of the whole numpy array from each example, and then divide each example by the standard deviation of the whole numpy array. But for picture datasets, it is simpler and more convenient and works almost as well to just divide every row of the dataset by 255 (the maximum value of a pixel channel).

Let's standardize our dataset.

train_set_x = train_set_x_flatten/255.

test_set_x = test_set_x_flatten/255.Common steps for pre-processing a new dataset are:

- Figuring it out the dimensions and shapes of the problem (m_train, m_test, num_px, ...)

- Reshaping the datasets such that each example is now a vector of size (num_px * num_px * 3, 1)

- "Standardize" the data

It's time to design a simple algorithm to distinguish cat images from non-cat images.

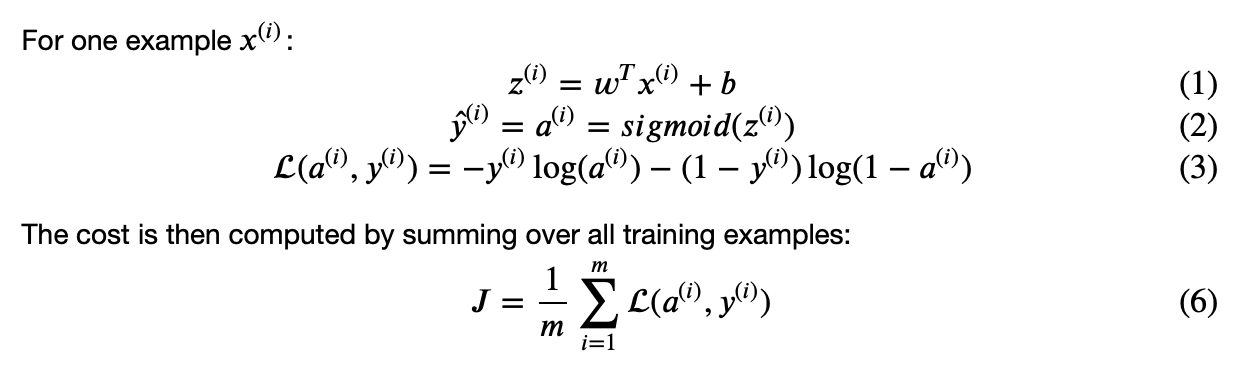

To build a Logistic Regression, using a Neural Network mindset we need to understand the mathematical expression.

Mathematical expression of the algorithm:

Key steps: In this exercise, I have learnt how to:

- Initialize the parameters of the model

- Learn the parameters for the model by minimizing the cost

- Use the learned parameters to make predictions (on the test set)

- Analyse the results and conclude

The main steps for building a Neural Network are:

- Defininng the model structure (such as number of input features)

- Initializing the model's parameters

- Loop:

- Calculate current loss (forward propagation)

- Calculate current gradient (backward propagation)

- Update parameters (gradient descent)

As you've seen in the figure above, we need to compute sigmoid( w^T x + b) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(w^T x + b)}}$ to make predictions by using using np.exp().

# GRADED FUNCTION: sigmoid

def sigmoid(z):

s = 1/(1+np.exp(-z))

return sprint ("sigmoid([0, 2]) = " + str(sigmoid(np.array([0,2]))))sigmoid([0, 2]) = [0.5 0.88079708]

Implementing parameter initialization in the cell below to initialize w as a vector of zeros.

# GRADED FUNCTION: initialize_with_zeros

def initialize_with_zeros(dim):

"""

This function creates a vector of zeros of shape (dim, 1) for w and initializes b to 0.

Argument:

dim -- size of the w vector we want (or number of parameters in this case)

Returns:

w -- initialized vector of shape (dim, 1)

b -- initialized scalar (corresponds to the bias)

"""

w = np.zeros([dim,1])

b = 0

assert(w.shape == (dim, 1))

assert(isinstance(b, float) or isinstance(b, int))

return w, bdim = 2

w, b = initialize_with_zeros(dim)

print ("w = " + str(w))

print ("b = " + str(b))w = [[0.]

[0.]]

b = 0

Now that my parameters are initialized, I can do the "forward" and "backward" propagation steps for learning the parameters.

Implementing a function propagate() that computes the cost function and its gradient.

Forward Propagation:

- get X

- compute

$A = \sigma(w^T X + b) = (a^{(0)}, a^{(1)}, ..., a^{(m-1)}, a^{(m)})$ - calculate the cost function:

$J = -\frac{1}{m}\sum_{i=1}^{m}y^{(i)}\log(a^{(i)})+(1-y^{(i)})\log(1-a^{(i)})$

Here are the two formulas that I will be using:

# GRADED FUNCTION: propagate

def propagate(w, b, X, Y):

m = X.shape[1]

# FORWARD PROPAGATION (FROM X TO COST)

A = sigmoid(np.dot(w.T,X)+b) # compute activation

cost = (-1/m)*( np.dot(Y,np.log(A).T) + np.dot((1-Y),np.log(1-A).T) ) # compute cost

# BACKWARD PROPAGATION (TO FIND GRAD)

dw = (1/m)*( np.dot(X,(A-Y).T))

db = (1/m)*np.sum((A-Y))

assert(dw.shape == w.shape)

assert(db.dtype == float)

cost = np.squeeze(cost)

assert(cost.shape == ())

grads = {"dw": dw,

"db": db}

return grads, costw, b, X, Y = np.array([[1],[2]]), 2, np.array([[1,2],[3,4]]), np.array([[1,0]])

grads, cost = propagate(w, b, X, Y)

print ("dw = " + str(grads["dw"]))

print ("db = " + str(grads["db"]))

print ("cost = " + str(cost))dw = [[0.99993216]

[1.99980262]]

db = 0.49993523062470574

cost = 6.000064773192205

- I have initialized your parameters.

- I can able to compute a cost function and its gradient.

- Now, I want to update the parameters using gradient descent.

Writing optimization function. My goal is to learn

# GRADED FUNCTION: optimize

def optimize(w, b, X, Y, num_iterations, learning_rate, print_cost = False):

"""

This function optimizes w and b by running a gradient descent algorithm

Arguments:

w -- weights, a numpy array of size (num_px * num_px * 3, 1)

b -- bias, a scalar

X -- data of shape (num_px * num_px * 3, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (containing 0 if non-cat, 1 if cat), of shape (1, number of examples)

num_iterations -- number of iterations of the optimization loop

learning_rate -- learning rate of the gradient descent update rule

print_cost -- True to print the loss every 100 steps

Returns:

params -- dictionary containing the weights w and bias b

grads -- dictionary containing the gradients of the weights and bias with respect to the cost function

costs -- list of all the costs computed during the optimization, this will be used to plot the learning curve.

basically we need to write down two steps and iterate through them:

1) Calculate the cost and the gradient for the current parameters by using propagate().

2) Update the parameters using gradient descent rule for w and b.

"""

costs = []

for i in range(num_iterations):

# Cost and gradient calculation

grads, cost = propagate(w, b, X, Y)

# Retrieve derivatives from grads

dw = grads["dw"]

db = grads["db"]

# update rule

w = w - learning_rate * dw

b = b - learning_rate * db

# Record the costs

if i % 100 == 0:

costs.append(cost)

# Print the cost every 100 training examples

if print_cost and i % 100 == 0:

print ("Cost after iteration %i: %f" %(i, cost))

params = {"w": w,

"b": b}

grads = {"dw": dw,

"db": db}

return params, grads, costsparams, grads, costs = optimize(w, b, X, Y, num_iterations= 100, learning_rate = 0.009, print_cost = False)

print ("w = " + str(params["w"]))

print ("b = " + str(params["b"]))

print ("dw = " + str(grads["dw"]))

print ("db = " + str(grads["db"]))

print(costs)w = [[0.1124579 ]

[0.23106775]]

b = 1.5593049248448891

dw = [[0.90158428]

[1.76250842]]

db = 0.4304620716786828

[array(6.00006477)]

The previous function will output the learned w and b and now I am able to use w and b to predict the labels for a dataset X.

Now I am going to implementing the predict() function. There is two steps to computing predictions:

-

Calculate

$\hat{Y} = A = \sigma(w^T X + b)$ -

Convert the entries of a into 0 (if activation <= 0.5) or 1 (if activation > 0.5), stores the predictions in a vector

Y_prediction. I am using anif/elsestatement in aforloop (though there is also a way to vectorize this).

# GRADED FUNCTION: predict

def predict(w, b, X):

'''

Predicting whether the label is 0 or 1 using learned logistic regression parameters (w, b)

Arguments:

w -- weights, a numpy array of size (num_px * num_px * 3, 1)

b -- bias, a scalar

X -- data of size (num_px * num_px * 3, number of examples)

Returns:

Y_prediction -- a numpy array (vector) containing all predictions (0/1) for the examples in X

'''

m = X.shape[1]

Y_prediction = np.zeros((1,m))

w = w.reshape(X.shape[0], 1)

# Compute vector "A" predicting the probabilities of a cat being present in the picture

A = sigmoid(np.dot(w.T,X)+b)

for i in range(A.shape[1]):

# Convert probabilities A[0,i] to actual predictions p[0,i]

if A[0,i] <= 0.5:

Y_prediction[0, i] = 0

else:

Y_prediction[0, i] = 1

assert(Y_prediction.shape == (1, m))

return Y_predictionprint ("predictions = " + str(predict(w, b, X)))predictions = [[1. 1.]]

I've implemented several functions that:

- Initialize (w,b)

- Optimize the loss iteratively to learn parameters (w,b):

- computing the cost and its gradient

- updating the parameters using gradient descent

- Use the learned (w,b) to predict the labels for a given set of examples

Now we can see how the overall model is structured by putting together all the building blocks (functions implemented in the previous parts) together, in the right order.

Implementing the model function by using the following notation: - Y_prediction for the predictions on the test set - Y_prediction_train for the predictions on the train set - w, costs, grads for the outputs of optimize()

# GRADED FUNCTION: model

def model(X_train, Y_train, X_test, Y_test, num_iterations = 2000, learning_rate = 0.5, print_cost = False):

"""

Building the logistic regression model by calling the function you've implemented previously

Arguments:

X_train -- training set represented by a numpy array of shape (num_px * num_px * 3, m_train)

Y_train -- training labels represented by a numpy array (vector) of shape (1, m_train)

X_test -- test set represented by a numpy array of shape (num_px * num_px * 3, m_test)

Y_test -- test labels represented by a numpy array (vector) of shape (1, m_test)

num_iterations -- hyperparameter representing the number of iterations to optimize the parameters

learning_rate -- hyperparameter representing the learning rate used in the update rule of optimize()

print_cost -- Set to true to print the cost every 100 iterations

Returns:

d -- dictionary containing information about the model.

"""

# initialize parameters with zeros (≈ 1 line of code)

w, b = initialize_with_zeros(X_train.shape[0])

# Gradient descent (≈ 1 line of code)

parameters, grads, costs = optimize(w, b, X_train, Y_train, num_iterations, learning_rate, print_cost)

# Retrieve parameters w and b from dictionary "parameters"

w = parameters["w"]

b = parameters["b"]

# Predict test/train set examples (≈ 2 lines of code)

Y_prediction_test = predict(w, b, X_test)

Y_prediction_train = predict(w, b, X_train)

# Print train/test Errors

print("train accuracy: {} %".format(100 - np.mean(np.abs(Y_prediction_train - Y_train)) * 100))

print("test accuracy: {} %".format(100 - np.mean(np.abs(Y_prediction_test - Y_test)) * 100))

d = {"costs": costs,

"Y_prediction_test": Y_prediction_test,

"Y_prediction_train" : Y_prediction_train,

"w" : w,

"b" : b,

"learning_rate" : learning_rate,

"num_iterations": num_iterations}

return dRun the following cell to train the model.

d = model(train_set_x, train_set_y, test_set_x, test_set_y, num_iterations = 2000, learning_rate = 0.005, print_cost = True)Cost after iteration 0: 0.693147

Cost after iteration 100: 0.584508

Cost after iteration 200: 0.466949

Cost after iteration 300: 0.376007

Cost after iteration 400: 0.331463

Cost after iteration 500: 0.303273

Cost after iteration 600: 0.279880

Cost after iteration 700: 0.260042

Cost after iteration 800: 0.242941

Cost after iteration 900: 0.228004

Cost after iteration 1000: 0.214820

Cost after iteration 1100: 0.203078

Cost after iteration 1200: 0.192544

Cost after iteration 1300: 0.183033

Cost after iteration 1400: 0.174399

Cost after iteration 1500: 0.166521

Cost after iteration 1600: 0.159305

Cost after iteration 1700: 0.152667

Cost after iteration 1800: 0.146542

Cost after iteration 1900: 0.140872

train accuracy: 99.04306220095694 %

test accuracy: 70.0 %

Comment: Training accuracy is close to 100%. This is a good sanity check: I guss my model is working and has high enough capacity to fit the training data. Test error is 70%. It is actually not bad for this simple model, given the small dataset I have used and that logistic regression is a linear classifier.

Also, I have seen that the model is clearly overfitting the training data. we have to reduce overfitting, for example by using regularization. Using the code below (and changing the index variable) we can look at predictions on pictures of the test set.

# Example of a picture that was wrongly classified.

index = 21

plt.imshow(test_set_x[:,index].reshape((num_px, num_px, 3)))

print ("y = " + str(test_set_y[0,index]) + ", you predicted that it is a " + classes[int(d["Y_prediction_test"][0,index])].decode("utf-8") + " picture.")y = 0, you predicted that it is a non-cat picture.

# Example of a picture that was correctly classified.

index = 9

plt.imshow(test_set_x[:,index].reshape((num_px, num_px, 3)))

print ("y = " + str(test_set_y[0,index]) + ", you predicted that it is a " + classes[int(d["Y_prediction_test"][0,index])].decode("utf-8") + " picture.")y = 1, you predicted that it is a cat picture.

Let's also plot the cost function and the gradients.

# Plot learning curve (with costs)

costs = np.squeeze(d['costs'])

plt.plot(costs)

plt.ylabel('cost')

plt.xlabel('iterations (per hundreds)')

plt.title("Learning rate =" + str(d["learning_rate"]))

plt.show()Interpretation: I can see that the cost decreasing. It shows that the parameters are being learned. However, I could train the model even more on the training seta and try to increase the number of iterations in the cell above and rerun the cells. I can also see that the training set accuracy goes up, but the test set accuracy goes down. This is called overfitting.

Let's analyze it further, and examine possible choices for the learning rate

In order for Gradient Descent to work we must choose the learning rate wisely. The learning rate

Let's compare the learning curve of our model with several choices of learning rates by running the cell below. This should take about 1 minute. Feel free also to try different values than the three I have initialized the learning_rates variable to contain, and see what happens.

learning_rates = [0.01, 0.001, 0.0001]

models = {}

for i in learning_rates:

print ("learning rate is: " + str(i))

models[str(i)] = model(train_set_x, train_set_y, test_set_x, test_set_y, num_iterations = 1500, learning_rate = i, print_cost = False)

print ('\n' + "-------------------------------------------------------" + '\n')

for i in learning_rates:

plt.plot(np.squeeze(models[str(i)]["costs"]), label= str(models[str(i)]["learning_rate"]))

plt.ylabel('cost')

plt.xlabel('iterations')

legend = plt.legend(loc='upper center', shadow=True)

frame = legend.get_frame()

frame.set_facecolor('0.90')

plt.show()learning rate is: 0.01

train accuracy: 99.52153110047847 %

test accuracy: 68.0 %

-------------------------------------------------------

learning rate is: 0.001

train accuracy: 88.99521531100478 %

test accuracy: 64.0 %

-------------------------------------------------------

learning rate is: 0.0001

train accuracy: 68.42105263157895 %

test accuracy: 36.0 %

-------------------------------------------------------

Interpretation:

-

Different learning rates give different costs and thus different predictions results.

-

If the learning rate is too large (0.01), the cost may oscillate up and down. It may even diverge (though in this example, using 0.01 still eventually ends up at a good value for the cost).

-

A lower cost doesn't mean a better model. We have to check if there is possibly overfitting. It happens when the training accuracy is a lot higher than the test accuracy.

-

In deep learning:

- Choose the learning rate that better minimizes the cost function.

- If the model overfits, use other optimization techniques to reduce overfitting.

We can use our own image and see the output of the model. To do that: 1. Click on "File" in the upper bar of this notebook. 2. Add your image to this file directory, in the "images" folder 3. Change your image's name in the following code 4. Run the code and check if the algorithm is right (1 = cat, 0 = non-cat)!

##(PUT YOUR IMAGE NAME)

my_image = "cat_in_iran.jpg" # change this to the name of your image file

# Preprocess the image to fit model algorithm.

fname = "images/" + my_image

image = np.array(plt.imread(fname))

my_image = np.array(Image.fromarray(image).resize([num_px,num_px])).reshape((1, num_px*num_px*3)).T

my_predicted_image = predict(d["w"], d["b"], my_image)

plt.imshow(image)

print("y = " + str(np.squeeze(my_predicted_image)) + ", your algorithm predicts a \"" + classes[int(np.squeeze(my_predicted_image)),].decode("utf-8") + "\" picture.")- Preprocessing the dataset is important.

- Implemented each function separately: initialize(), propagate(), optimize(). Then I built a model().

- Tuning the learning rate (which is an example of a "hyperparameter") can make a big difference to the algorithm.