So... I may have taken this a little too far... But it was fun and I got to use some new things I had never used before.

If you are wondering why this took so long and looking for anyone to blame, see here. A special thanks to the sick kid who decided to put my daughter's toys in his mouth.

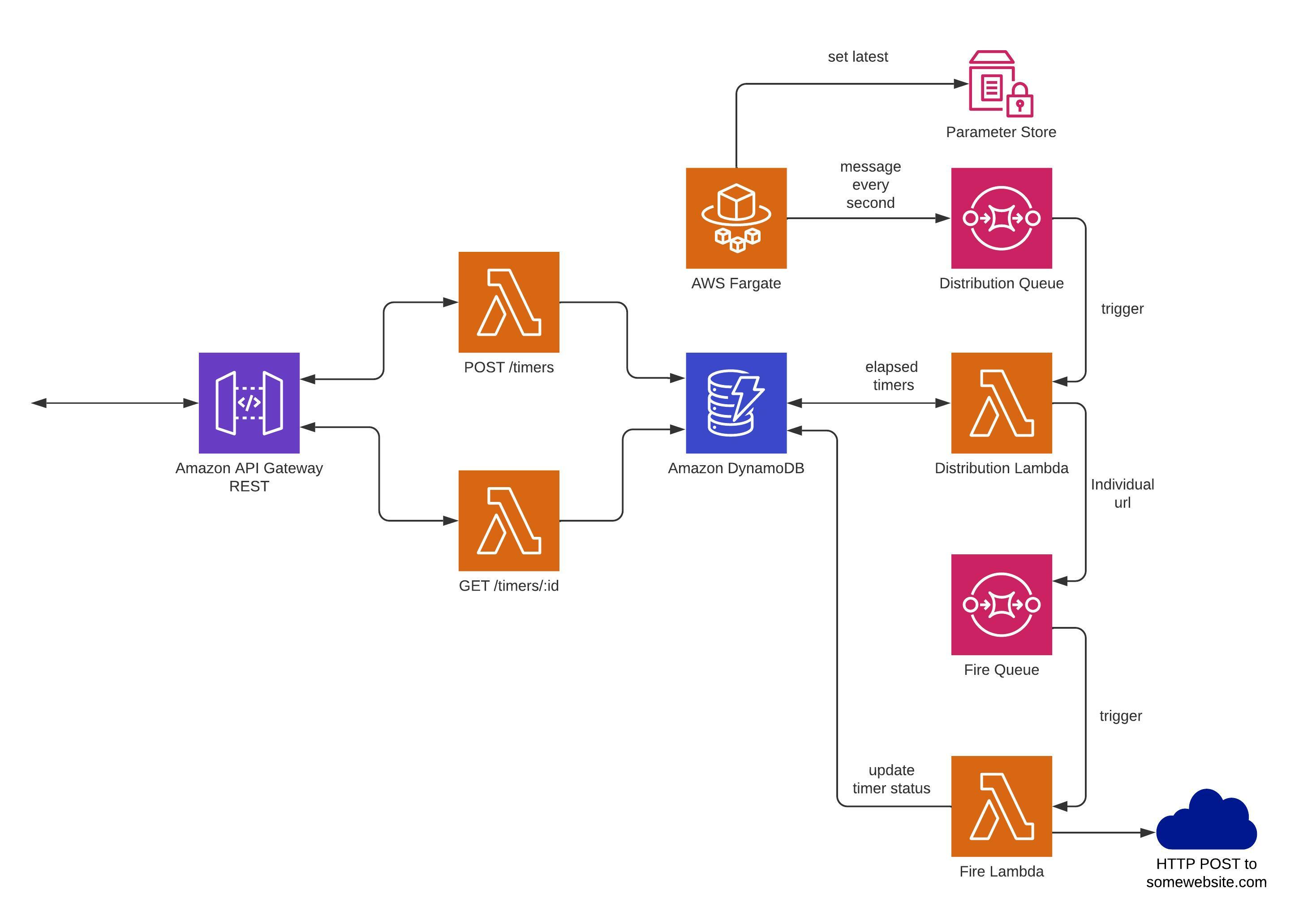

The overall design hinges on two distinct parts:

- API - This includes a REST API Gateway, backed by two lambda functions, controlling the POST and GET requests for /timers route.

- Backend - This includes everything that is responsible for sending a POST message when a timer elapses.

The infrastructure is built with AWS CDK in Typescript, the actual pieces of code (4 lambdas and one script) are written in python, and a simple Dockerfile is used for Fargate.

The API is managed by a simple AWS REST API Gateway, with a lambda function for handling each route.

-

POST route is responsible for creating new timers. POST route generates a new UUID (UUID4), and that is used to save the timer in two places in the DB:

- An entry indexed by the timer ID, which contains the (epoch) time to fire, and a status.

- An entry indexed by the time to fire which contains a map of "id -> url".

This double schema is intended to negate the need for expensive scan operations (equivalent to a SELECT * WHERE... SQL query) when querying for elapsed timers. The purpose of negating this is twofold: It is cheaper, and it is (much) faster - pretty much constant query time no matter how many timers have been created. The Route's body is verified by API Gateway. (in case you're wondering why there are no structure checks in Lambda code)

- GET route simply returns the timer id, number of seconds remaining until fire, and a status (ACTIVE/SUCCESS) depending on if the timer has already fired.

The backend is comprised of three main parts:

- Trigger - This component, built from an AWS Fargate-backed python application, with an SSM parameter and an SQS queue (Distribution queue) is responsible for triggering url firing flow every second. It uses the SSM parameter for non-volatile storage of the latest second for which the flow was triggered (this is in case the application fails and there needs to be a firing of missed timers), where the messages sent to SQS queue are simply the current epoch second (e.g. 1651765337 for Thursday, May 5, 2022 3:42:17 PM GMT).

- Distribution lambda - This lambda function reads the timer entry for that specific second from DB, and if it exists writes a message for each timer that is scheduled to set off in that second to Fire SQS queue.

- Fire lambda - receives a pair of (id, url) as input from Fire queue, sends a POST message to the URL, and then updates the status of the timer entry with the id in DB.

Note that there's no real need to deploy to your personal account. I have a personal account and can deploy the solution there. (and have deployed it there) I have a 10USD limit on my account but testing the solution cost me 0.14USD so far so I think I can manage.

To deploy to your personal account you will need the follwing installed:

- A personal AWS account

- AWS CLI V2 - See here for installation instructions.

- AWS CDK - See here for installation instructions and prerequisites. You are probably also going to need to bootstrap your account, unless you have deployed stacks using CDK before.

- An IAM user profile with credentials (access and secret keys) defined locally using

aws configure- See here for profile creation instructions and here for IAM user creation instructions. For simplicity you can create a user with administrator priviliges, although it is not a good security practice.

To deploy navigate to src directory and use command

> cdk deploy --profile <your_profile> --context account=<your_account_id>for example:

> cdk deploy --profile dev_profile --context account=0123456789The CDK output will include your public API endpoint.

Alternatively, a stack with an API endpoint can be supplied on demand.

Why NoSQL? It is true that currently we are working with a fixed schema, allowing for both SQL and Non-SQL databases, but there doesn't seem to be any need now or in the future, for join operations. Thus, a simple read-write storage is good enough. Other options exist, of course.

Why DynamoDB? First, if you plan your schema correctly, and expect many distinct keys (which we are), DynamoDB offers incredibly fast query times, with super-high availability.

Why not DynamoDB? To be truthful, I am not sure if DynamoDB is the best choice in this case. A better choice I think is Amazon DocumentDB, which is an AWS managed version of MongoDB. The reason I think this is a better option stems from the operation executed in the POST lambda - updating a the map of URLs for a specific second. This update should happen if an entry for this specific second already exists, and an entry should be created if it does not (with the id,url pair already in the map). It is easy to see that this operation (try to update, if failed write new entry) needs to be atomic. Unfortunately, DynamoDB currently does not support this update-or-create operation in an atomic way, whereas MongoDB's findAndUpdateOne operation which (I think) can be used for this is atomic. However, selecting DocumentDB would have been a money-waster as it is managed on EC2 instances and is pretty expensive, at least for the amount of money I'm willing to spend on a home assignment.

At a first glance it would seem that the entire fargate-backed application whose only purpose is to generate a timer for the url firing mechanism is redundant. It would be better to use, say, AWS EventBridge and trigger the distribution lambda every second. Unfortunately cron expressions for EventBridge only support a maximum of per-minute granularity. Thus, a need for per-second timers arose. But even that is not trivial to create. Lets assume we have a timer that works like this:

while True:

triggering_mechanism()

sleep(1)If the triggering_mechanism() function takes 0.4 seconds, then the second time we are triggering we will start 1.4 seconds after the loop was first started, the third time after 2.8 seconds, and the fourth after 4.2 seconds. It would appear as though we missed an entire second. Thus, something like the following would be more appropriate:

while True:

triggering_mechanism()

sleep(0.2)But now triggering can occur twice in the same second, and double fires will occur. Note that no matter how much time we choose to sleep, or how long the triggering mechanism takes, we will always be either below or above one second, each with its problems. It would appear as though this problem is not as trivial as would seem, and therefore has a more complex solution in code.

A good question to ask is "How well does this solution scale up?". The answer? Very well, albeit with some minor changes. Usual bottlenecks for scaling are around DB access. If my DB only supports 100 writes per-second then I am going to be capped at handling 100 POST requests per-second. (or slightly less) DynamoDB can scale very well with increasing write demands. This solution also plays well with horizontal scaling.

The number of timers that can be triggered per-second in this solution is capped because of technical reasons:

- Each DynamoDB attribute can hold no more than 400KB of data. If the average entry is about 100 bytes long, then no more than 4000 timers can go off every second.

- Lambda function concurrency has strict quotas, of ~6000 per account (IIRC) per second. This is less of a problem, as the average post request takes much less than a second. (Except the first one because of cold starts)

Since the data held in the database is conducive to sharding, one approach can be to split it between N tables, based on the modulo N of the ID. If we assume UUID4s are distributed evenly (fair assumption), then each shard will hold ~the same amount of timers, mitigating the first problem. This solution also has its share of problems, as changing N might prove tricky. (If id=17 and N changes from 9 to 11, then the shard changes from 8 to 6) For problem 2 quotas can be increased, or sharding can be split across accounts. In the end, if we are looking at supporting a truly gigantic number of timers, perhaps serverless is not the way for us, or at least Lambda is not. (Fargate is great)

-

Current solution may malfunction with immediate (0 hours, 0 minutes, 0 seconds) and 1-second (0 hours, 0 minutes, 1 second) timers. This is because these timers are valid, but can be saved to DB after the relevant second trigger already happened. This can be solved by checking if timer is a 0-second (resp. 1-second) timer in POST route lambda and then firing it imediately (resp. waiting one second and then firing it) by sending it as a message to Fire SQS queue.

-

If some AWS services (like writing to DynamoDB on POST message) are delayed, for whatever reason, short timers (2-3 second ones) can be registered only after their respective second has passed. (since computing the exact second to fire is done prior to writing to DB for obvious reasons) A solution to this can be some cleanup application that runs in 1-minute intervals and checks for unfired timers from the past 90 seconds. This solution will require a small change in DB schema.