Expand All Sections

- Create a folder

- Open the folder in VSCode

- Run the following command:

dotnet new console

To run the app:

Either,

- F5

Or,

- In the VSCode Terminal:

dotnet run

To compile a Release build:

dotnet run -c Release

using System;

namespace MyNamespace

{

public abstract class MySuperClass

{

public MySuperClass()

{

}

public abstract void Output();

}

public class MySubClass : MySuperClass

{

private int val;

public MySubClass(int val = 5)

{

this.val = val;

}

public override void Output()

{

Console.WriteLine($"{this.val}");

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MySuperClass myClass = new MySubClass();

myClass.Output(); // output 5

myClass = new MySubClass(10);

myClass.Output(); // output 10

}

}

}using System;

namespace MyNamespace

{

public struct MyStruct1

{

public int x;

public int y;

}

public struct MyStruct2

{

public MyStruct2(int x, int y)

{

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public int x;

public int y;

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MyStruct1 myStruct1 = new MyStruct1();

myStruct1.x = 5;

myStruct1.y = 6;

Console.WriteLine($"{myStruct1.x}, {myStruct1.y}"); // output: 5, 6

MyStruct2 myStruct2 = new MyStruct2(7, 8);

Console.WriteLine($"{myStruct2.x}, {myStruct2.y}"); // output: 7, 8

}

}

}using System;

namespace MyNamespace

{

enum MyEnum

{

Val1, // 0

Val2, // 1

Val3 = 6, // 6

Val4, // 7

Val5, // 8

Val6 // 9

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine(MyEnum.Val2); // output: Val2

int val = (int)MyEnum.Val2; // enum to int conversion

Console.WriteLine(val); // output: 1

var en = (MyEnum)8; // int to enum conversion

Console.WriteLine(en); // output: Val5

}

}

}NOTE: Once a case matches, all statements following that case (including other cases!) will be executed until a break or return statement is encountered.

It should also be noted, however, that leaving out break statements is generally considered bad practice.

using System;

namespace MyNamespace

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

int x = 10;

switch (x)

{

case 5:

Console.WriteLine("Value of x is 5");

break;

case 10:

Console.WriteLine("Value of x is 10");

break;

case 15:

// if there is no break statement

// both "15" and "20" will trigger

// the "20" case

case 20:

Console.WriteLine("Value of x is 15 or 20");

break;

default:

Console.WriteLine("Unknown value");

break;

}

}

}

}using System;

namespace MyNamespace

{

public class MyClass

{

public MyClass()

{

}

public void TriggerEvent()

{

Changed(10);

}

public event Action<int> Changed;

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

MyClass myClass = new MyClass();

myClass.Changed += ChangeHandler;

myClass.TriggerEvent(); // output: 10

}

static void ChangeHandler(int val)

{

Console.WriteLine($"{val}");

}

}

}String Formatter:

Console.WriteLine(string.Format("{0} & {1}", var1, var2));String Interpolation:

Console.WriteLine($"{var1} & {var2}");Displaying Bytes

To display the bytes for a number, use: Convert.ToString(num, toBase: 2)

using System;

using System.Text.Json;

public class Car

{

public string Model

{

get { return "Volkswagon"; }

}

public string Make

{

get { return "Golf"; }

}

public CarDetails Details

{

get { return new CarDetails(); }

}

}

public class CarDetails

{

public int Year

{

get { return 2017; }

}

public float Price

{

get { return 20000f; }

}

public Condition Condition

{

get { return Condition.EXCELLENT; }

}

}

public enum Condition

{

EXCELLENT,

GOOD,

POOR

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

Car car = new Car();

var options = new JsonSerializerOptions { WriteIndented = true };

Console.WriteLine(JsonSerializer.Serialize(car, typeof(Car), options));

// Output:

// {

// "Model": "Volkswagon",

// "Make": "Golf",

// "Details": {

// "Year": 2017,

// "Price": 20000,

// "Condition": 0

// }

// }

}

}Generally, the two fastest ways to check the parity of a number (whether it is even or odd) are the following:

Using bitwise &

This is normally the fastest method.

Checks if the last binary digit of the number is 1 (in which case it is odd).

private static bool isEven(int i)

{

return (i & 1) == 0;

}Testing the remainder

This can be easiest to read.

Checks if there is any remainder after dividing by 2 (in which case it is odd).

private static bool isEven(int i)

{

return (i % 2) == 0;

}To achieve an even distribution of HashCodes, the following technique is generally used:

- Combine the properties used to test for equality (i.e. in

Equals()). - Add some prime numbers to improve the distribution.

There are several approaches to achieve this:

Method 1: XOR and Primes

public sealed class Point3D

{

private readonly double x;

private readonly double y;

private readonly double z;

private readonly ReadOnlyCollection<string> attrs;

public Point3D(double x, double y, double z, IEnumerable<string> attrs)

{

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.z = z;

this.attrs = new ReadOnlyCollection<string>(attrs.ToList());

}

public double X => this.x;

public double Y => this.y;

public double Z => this.z;

public ReadOnlyCollection<string> Attrs => this.attrs;

public override bool Equals(object other)

{

return other is Point3D p

&& p.X == X

&& p.Y == Y

&& p.Z == Z

&& p.Attrs == Attrs; // simplified for brevity

}

public override int GetHashCode()

{

unchecked // Allow arithmetic overflow, numbers will just "wrap around"

{

int hashcode = 1430287;

hashcode = hashcode * 7302013 ^ X.GetHashCode();

hashcode = hashcode * 7302013 ^ Y.GetHashCode();

hashcode = hashcode * 7302013 ^ Z.GetHashCode();

hashcode = hashcode * 7302013 ^ Attrs.GetHashCode();

return hashcode;

}

}

}Method 2: Use a Tuple

With the introduction of tuples in C# 7, this can be simplified to the following:

public sealed class Point3D

{

private readonly double x;

private readonly double y;

private readonly double z;

private readonly ReadOnlyCollection<string> attrs;

public Point3D(double x, double y, double z, IEnumerable<string> attrs)

{

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.z = z;

this.attrs = new ReadOnlyCollection<string>(attrs.ToList());

}

public double X => this.x;

public double Y => this.y;

public double Z => this.z;

public ReadOnlyCollection<string> Attrs => this.attrs;

public override bool Equals(object other)

{

return other is Point3D p

&& p.X == X

&& p.Y == Y

&& p.Z == Z

&& p.Attrs == Attrs; // simplified for brevity

}

public override int GetHashCode() => (X, Y, Z, Attrs).GetHashCode();

}Method 2: Helper Struct

This following approach is taken from Rehan Saeed's "GetHasCode Made Easy":

// MIT Licensed

// Copyright (c) 2019 Muhammad Rehan Saeed

// Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy

// of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal

// in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights

// to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell

// copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is

// furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

// The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all

// copies or substantial portions of the Software.

// THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR

// IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY,

// FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE

// AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER

// LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM,

// OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE

// SOFTWARE.

/// <summary>

/// A hash code used to help with implementing <see cref="object.GetHashCode()"/>.

/// </summary>

public struct HashCode : IEquatable<HashCode>

{

private const int EmptyCollectionPrimeNumber = 19;

private readonly int value;

/// <summary>

/// Initializes a new instance of the <see cref="HashCode"/> struct.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="value">The value.</param>

private HashCode(int value) => this.value = value;

/// <summary>

/// Performs an implicit conversion from <see cref="HashCode"/> to <see cref="int"/>.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="hashCode">The hash code.</param>

/// <returns>The result of the conversion.</returns>

public static implicit operator int(HashCode hashCode) => hashCode.value;

/// <summary>

/// Implements the operator ==.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="left">The left.</param>

/// <param name="right">The right.</param>

/// <returns>The result of the operator.</returns>

public static bool operator ==(HashCode left, HashCode right) => left.Equals(right);

/// <summary>

/// Implements the operator !=.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="left">The left.</param>

/// <param name="right">The right.</param>

/// <returns>The result of the operator.</returns>

public static bool operator !=(HashCode left, HashCode right) => !(left == right);

/// <summary>

/// Takes the hash code of the specified item.

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">The type of the item.</typeparam>

/// <param name="item">The item.</param>

/// <returns>The new hash code.</returns>

public static HashCode Of<T>(T item) => new HashCode(GetHashCode(item));

/// <summary>

/// Takes the hash code of the specified items.

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">The type of the items.</typeparam>

/// <param name="items">The collection.</param>

/// <returns>The new hash code.</returns>

public static HashCode OfEach<T>(IEnumerable<T> items) =>

items == null ? new HashCode(0) : new HashCode(GetHashCode(items, 0));

/// <summary>

/// Adds the hash code of the specified item.

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">The type of the item.</typeparam>

/// <param name="item">The item.</param>

/// <returns>The new hash code.</returns>

public HashCode And<T>(T item) =>

new HashCode(CombineHashCodes(this.value, GetHashCode(item)));

/// <summary>

/// Adds the hash code of the specified items in the collection.

/// </summary>

/// <typeparam name="T">The type of the items.</typeparam>

/// <param name="items">The collection.</param>

/// <returns>The new hash code.</returns>

public HashCode AndEach<T>(IEnumerable<T> items)

{

if (items == null)

{

return new HashCode(this.value);

}

return new HashCode(GetHashCode(items, this.value));

}

/// <inheritdoc />

public bool Equals(HashCode other) => this.value.Equals(other.value);

/// <inheritdoc />

public override bool Equals(object obj)

{

if (obj is HashCode)

{

return this.Equals((HashCode)obj);

}

return false;

}

/// <summary>

/// Throws <see cref="NotSupportedException" />.

/// </summary>

/// <returns>Does not return.</returns>

/// <exception cref="NotSupportedException">Implicitly convert this struct to an <see cref="int" /> to get the hash code.</exception>

[EditorBrowsable(EditorBrowsableState.Never)]

public override int GetHashCode() =>

throw new NotSupportedException(

"Implicitly convert this struct to an int to get the hash code.");

private static int CombineHashCodes(int h1, int h2)

{

unchecked

{

// Code copied from System.Tuple so it must be the best way to combine hash codes or at least a good one.

return ((h1 << 5) + h1) ^ h2;

}

}

private static int GetHashCode<T>(T item) => item?.GetHashCode() ?? 0;

private static int GetHashCode<T>(IEnumerable<T> items, int startHashCode)

{

var temp = startHashCode;

var enumerator = items.GetEnumerator();

if (enumerator.MoveNext())

{

temp = CombineHashCodes(temp, GetHashCode(enumerator.Current));

while (enumerator.MoveNext())

{

temp = CombineHashCodes(temp, GetHashCode(enumerator.Current));

}

}

else

{

temp = CombineHashCodes(temp, EmptyCollectionPrimeNumber);

}

return temp;

}

}This can then be used in the following manner:

public sealed class Point3D

{

private readonly double x;

private readonly double y;

private readonly double z;

private readonly ReadOnlyCollection<string> attrs;

public Point3D(double x, double y, double z, IEnumerable<string> attrs)

{

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.z = z;

this.attrs = new ReadOnlyCollection<string>(attrs.ToList());

}

public double X => this.x;

public double Y => this.y;

public double Z => this.z;

public ReadOnlyCollection<string> Attrs => this.attrs;

public override bool Equals(object other)

{

return other is Point3D p

&& p.X == X

&& p.Y == Y

&& p.Z == Z

&& p.Attrs == Attrs; // simplified for brevity

}

public override int GetHashCode()

{

return HashCode

.Of(this.X)

.And(this.Y)

.And(this.Z)

.AndEach(this.Attrs);

}

}

C# is an object-oriented, type-safe, and managed language that is compiled by .NET Framework to generate Microsoft Intermediate Language.

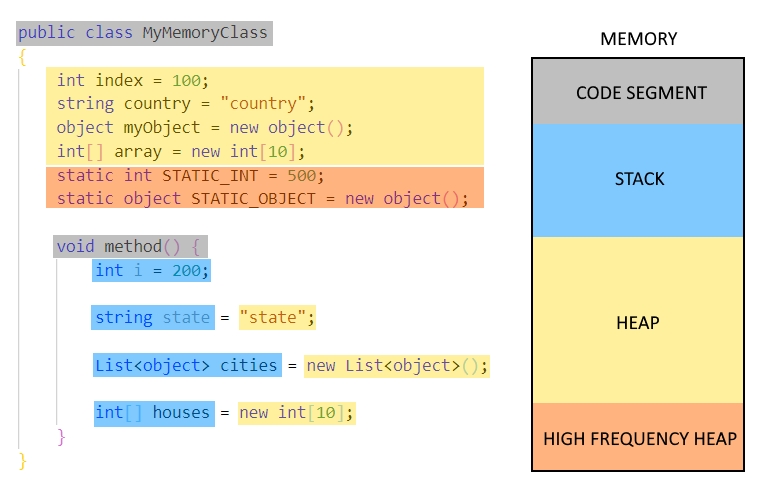

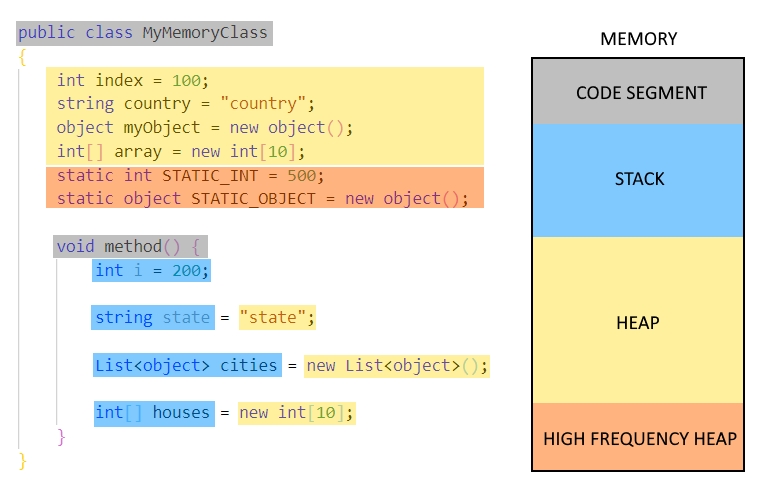

Stack: contiguous memory; consists of frames, each of which corresponds to a method; frames are pushed to the stack, or popped from the stack (hence "call-stack")

Heap: dynamic memory; objects are garbage collected on occasion.

- Contiguous memory.

- A stack consists of frames; each frame corresponds to a method/function call. A pointer references the current frame.

- When a method is called, all of its value-types (and pointers) are stored as a frame which is pushed onto the top of the stack.

- When the method returns, the frame for that method is popped off the stack (releasing the memory) and the pointer moves down to the next frame (i.e. the calling method).

- Dynamic memory which can be allocated at will.

- Can be fragmented since no guarantee which memory will be available at time objects are written.

- Creating a reference-type objects reserves memory for the objects, plus overhead for the pointer, plus overhead for memory management.

- When a reference-type objects is no longer referenced from the stack (or another objects), it is available to be garbage collected (which happens on occasion).

data + behaviour = class

As the name suggestions, Encapsulation is the combination of an objects data and behaviours in a single unit, e.g. a Class.

The benefits of encapsulation are:

- protection of data

- control of accessibility

- reduction of complexity (allows extensibility)

- improved maintainability (reduces coupling between objects)

Inheritance is the ability for multiple derived classes with similar features to be treated as objects of a common base class (or interface).

To prevent inheritance of a class, use 'sealed class'.

To stop inheritance of a virtual or abstract member, use 'sealed override myMember'.

using System;

namespace Sandbox

{

public class Car

{

public int Wheels { get { return 4; } }

}

public class Audi : Car { }

public class BMW : Car { }

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Car myAudi = new Audi();

Car myBmw = new BMW();

Console.WriteLine(myAudi.Wheels); // 4

Console.WriteLine(myBmw.Wheels); // 4

}

}

}

Polymorphism is the ability for derived classes to override properties of a common base class.

Static = Overloading

Dynamic = Interfaces, Abstract Classes, Virtual Members

using System;

namespace Sandbox

{

public interface IVehicle

{

int Wheels { get; }

}

public class Car : IVehicle

{

public int Wheels { get { return 4; } }

}

public class Bike : IVehicle

{

public int Wheels { get { return 2; } }

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

IVehicle myCar = new Car();

IVehicle myBike = new Bike();

Console.WriteLine(myCar.Wheels); // 4

Console.WriteLine(myBike.Wheels); // 2

}

}

}

Abstraction hiding internal implementation details by making a class/interface as 'abstract' as possible.

using System;

namespace Sandbox

{

public interface IVehicle

{

void Start();

}

public class Car : IVehicle

{

public void Start() { startEngine(); }

private void startEngine()

{

Console.WriteLine("Brrm brrm");

}

}

public class Bike : IVehicle

{

public void Start() { startPeddling(); }

private void startPeddling()

{

Console.WriteLine("Puff puff");

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

IVehicle myCar = new Car();

IVehicle myBike = new Bike();

myCar.Start(); // Brrm Brrm

myBike.Start(); // Puff puff

}

}

}

Class = Definition of an object.

Object = Instantiation of an class.

Simple names and simple implementations are better than complex or obscure ones.

Code in small pieces, and reuse the pieces.

Don't include features "just in case".

Don't test an object's state and then make decisions about the methods to call.

Tell the object what you want to do and assume that it knows enough about its internal state to make the right decision.

A principle is a goal, not a rule.

SRP: Single Responsibility Principle

OCP: Open-Close Principle

LSP: Liskov Substitution Principle

ISP: Interface Segregation Principle

DIP: Dependency Inversion Principle

The SOLID principles are described in greater detail further down, however in summary:

SRP: Single Responsibility Principle

A class should have only one reason to change (one responsibility per class).

OCP: Open-Close Principle

Objects should be open for extension, but closed for modification (easy to extend implementation, but cannot be change base implementation).

LSP: Liskov Substitution Principle

Every sub-class should be substitutable for its super-class (a client should not need to know whether it is dealing with a sub-class or a super-class).

ISP: Interface Segregation Principle

A client should not be forced to depend on methods it does not use (a sub-class should not be forced to implement methods it does not use).

DIP: Dependency Inversion Principle

Entities must depend on abstractions not on concretions (a high level module should not depend on a low level module; they should both depend on abstractions).

A class or function should have only one reason to change.

One responsibility per class/function, where "responsibility" means "a reason to change".

The responsibility should be entirely encapsulated by the class/function.

As an example, consider a module that compiles and prints a report. Imagine such a module can be changed for two reasons:

- The content of the report could change.

- The format of the report could change.

These two things change for very different causes; one substantive, and one cosmetic.

The Single Responsibility Principle says that these two aspects of the problem are really two separate responsibilities, and should, therefore, be in separate classes or modules.

It would be a bad design to couple two things that change for different reasons at different times.

The reason it is important to keep a class focused on a single concern is that it makes the class more robust. Continuing with the foregoing example, if there is a change to the report compilation process (i.e. the content), there is a greater danger that the printing (i.e. formatting) code will break if it is part of the same class.

An example of code that violates SRP is the following:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

public struct ValidatedOrder

{

public ValidatedOrder(int customerId, int orderId, List<string> items, float price)

{

this.CustomerId = customerId;

this.Id = orderId;

this.Items = items;

this.Price = price;

}

public int CustomerId;

public int Id;

public List<string> Items;

public float Price;

}

// OrderManager Responsibility: Process orders

public class OrderManager

{

private List<ValidatedOrder> orderCollection = new List<ValidatedOrder>();

// OrderManager Responsibility 1: Validate the order

public ValidatedOrder ValidateOrder(int customerId, int id)

{

//Code for validation

float price = 23.76f;

return new ValidatedOrder(customerId, id, new List<string>(), price);

}

// OrderManager Responsibility 2: Save the order

public bool SaveOrder(ValidatedOrder order)

{

//Code for saving order

orderCollection.Add(order);

return true;

}

// OrderManager Responsibility 3: Notify the customer

public void NotifyCustomer(int customerId)

{

//Code for notification

}

// OrderManager Responsibility 4: Produce report on orders

public float SumOfAllCustomerOrders(int customerId)

{

// SumOfAllCustomerOrders Responsibility 1: Query orders

var orders = this.orderCollection.Where(c => c.CustomerId == customerId);

// SumOfAllCustomerOrders Responsibility 2: Sum orders

float sum = 0;

foreach (ValidatedOrder order in orders)

{

sum += order.Price;

}

return sum;

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

int customerId = 2675376;

int orderId = 157;

OrderManager orderManager = new OrderManager();

ValidatedOrder orderInfo = orderManager.ValidateOrder(customerId, orderId);

orderManager.SaveOrder(orderInfo);

orderManager.NotifyCustomer(customerId);

float price = orderManager.SumOfAllCustomerOrders(customerId);

Console.WriteLine($"Spent today: {price}");

}

}Note OrderManager does all of the following:

ValidateOrder: Validating an order placed by customer and returns the final orderSaveOrder: Saving an order placed by the customer and returns true/falseNotifyCustomer: Notifies the customer order is placed

In addition, the SumOfAllCustomerOrders() method both queries the orders and processes the results.

To rectify this, the following changes might be made:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

public struct ValidatedOrder

{

public ValidatedOrder(int customerId, int orderId, List<string> items, float price)

{

this.CustomerId = customerId;

this.Id = orderId;

this.Items = items;

this.Price = price;

}

public int CustomerId;

public int Id;

public List<string> Items;

public float Price;

}

// OrderValidator Responsibility: Validate orders

public class OrderValidator

{

// OrderValidator Responsibility 1: Validate the order

public ValidatedOrder ValidateOrder(int customerId, int id)

{

//Code for validation

float price = 23.76f;

return new ValidatedOrder(customerId, id, new List<string>(), price);

}

}

// OrderDatabase Responsibility: Store order state

public class OrderDatabase

{

private List<ValidatedOrder> orderCollection = new List<ValidatedOrder>();

// OrderDatabase Responsibility 1: Set order state

public bool SaveOrder(ValidatedOrder order)

{

//Code for saving order

orderCollection.Add(order);

return true;

}

// OrderDatabase Responsibility 2: Get order state

public IEnumerable<ValidatedOrder> GetOrders(int customerId)

{

return this.orderCollection.Where(c => c.CustomerId == customerId); ;

}

}

// CustomerNotifier Responsibility: Notify customers

public class CustomerNotifier

{

// CustomerNotifier Responsibility 1: Notify the customer

public void NotifyCustomer(ValidatedOrder order)

{

//Code for notification

}

}

// OrderManager Responsibility: Process orders

public class OrderManager

{

private readonly OrderValidator orderValidator;

private readonly CustomerNotifier notifier;

private readonly OrderDatabase database;

public OrderManager(OrderValidator validator, CustomerNotifier notifier, OrderDatabase database)

{

this.orderValidator = validator;

this.notifier = notifier;

this.database = database;

}

// OrderManager Responsibility 1: Process an order to completion

public bool ProcessOrder(int customerId, int orderId)

{

ValidatedOrder orderInfo = orderValidator.ValidateOrder(customerId, orderId);

database.SaveOrder(orderInfo);

notifier.NotifyCustomer(orderInfo);

return true;

}

// OrderManager Responsibility 2: Produce report on orders

public float SumOfAllCustomerOrders(int customerId)

{

var orders = database.GetOrders(customerId);

float sum = 0;

foreach (ValidatedOrder order in orders)

{

sum += order.Price;

}

return sum;

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

OrderValidator orderValidator = new OrderValidator();

CustomerNotifier notifier = new CustomerNotifier();

OrderDatabase database = new OrderDatabase();

OrderManager orderManager = new OrderManager(orderValidator, notifier, database);

int customerId = 2675376;

int orderId = 157;

if (orderManager.ProcessOrder(customerId, orderId))

{

float price = orderManager.SumOfAllCustomerOrders(customerId);

Console.WriteLine($"Spent today: {price}");

}

}

}As can be seen, each class and each method now has a single responsibility, which satisfies the Single Responsibility Principle.

Rules of Thumb

To determine if SRP is being violated, try the following:

- Try to write a one line description of the class or method, if the description contains words like "And, Or, But or If" then that is a problem. * For the violating example above: "An OrderManager class that validates orders, saves orders and notifies the customer"

- Does the class constructor or method take more than three arguments/parameters?

- Does the class or method implementation seem too long? ("too long" can be hard to pin down)

- Does the class have low cohesion? ("cohension" = the degree to which the elements inside a module belong together)

Objects should be open for extension, but closed for modification

It should be easy to extend an implementation, but it should not be possible to change the base implementation.

An wall electrical socket is a good, real-world example of this principle.

- Electrical devices are not attached directly to the mains, they are plugged into a standard wall socket.

- The wall socket is always closed for modification (it cannot be changed once fitted).

- The wall socket can be extended however, by either plugging in an extension board or by fitting an adaptor (e.g. USB adaptor).

For a code example, consider the following:

using System;

public enum AccountType

{

Regular,

Salary

}

public class SavingAccount

{

private float balance;

public SavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public float CalculateInterest(AccountType accountType)

{

float interest = 0;

switch (accountType)

{

case AccountType.Regular:

interest = balance * 0.04f;

if (balance < 1000) interest -= balance * 0.02f;

if (balance < 50000) interest += balance * 0.04f;

break;

case AccountType.Salary:

interest = balance * 0.05f;

break;

default:

throw new Exception("Unknown account type");

}

return interest;

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

float initialBalance = 10000f;

SavingAccount acc = new SavingAccount(initialBalance);

Console.WriteLine(acc.CalculateInterest(AccountType.Regular));

}

}In this example, the implementation is not following the Open-Closed Principle because, if tomorrow the bank introduces a new AccountType, the CalculateInterest() method is always at risk of modification.

As a side note, this method is also not following the Single Responsibility Principle since the CalculateInterest() method is doing more than one thing (it is calculating interest for more than one account type).

To avoid this, OCP can be applied to produce the following alternative:

using System;

public interface ISavingAccount

{

float CalculateInterest();

}

public class RegularSavingAccount : ISavingAccount

{

private float balance;

public RegularSavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public float CalculateInterest()

{

float interest = balance * 0.04f;

if (balance < 1000) interest -= balance * 0.02f;

if (balance < 50000) interest += balance * 0.04f;

return interest;

}

}

public class SalarySavingAccount : ISavingAccount

{

private float balance;

public SalarySavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public float CalculateInterest()

{

return balance * 0.05f;

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

float initialBalance = 10000f;

ISavingAccount acc = new RegularSavingAccount(initialBalance);

Console.WriteLine(acc.CalculateInterest());

}

}In this case, there is no longer any need to modify the existing classes if a new account type is added; the new logic for the new account can be added by simply extending the functionality inherited from an interface. This now satisfies the Open-Close Principle.

In addition, the Single Responsibility Principle is also satisfied since each class or function is only doing one task.

Note: An interface is created here just as an example. There could be an abstract class of SavingAccount that is implemented by a new savings account type.

Every sub-class should be substitutable for its super-class.

A client should not need to know whether it is dealing with a sub-class or a super-class.

A real-world example of this principle - and its violation - is the act of replacing a light bulb.

- A standard exists for light bulb socket types.

- Assuming a new bulb meets the standard and provides the same illumination, the end user is not aware of whether the bulb is incandescent, flourescent or LED. This satisfies LSP.

- If the illumination provided by the new bulb no longer meets the end user's expectations, this violates LSP.

A code example is the following:

using System;

public interface ISavingAccount

{

bool CanWithdraw(float amount);

}

public class RegularSavingAccount : ISavingAccount

{

private float balance;

public RegularSavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public bool CanWithdraw(float amount)

{

float moneyAfterWithdrawal = balance - amount;

if (moneyAfterWithdrawal >= 1000)

{

return true;

}

else

return false;

}

}

public class SalarySavingAccount : ISavingAccount

{

private float balance;

public SalarySavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public bool CanWithdraw(float amount)

{

float moneyAfterWithdrawal = balance - amount;

if (moneyAfterWithdrawal >= 0)

{

return true;

}

else

return false;

}

}

public class FixDepositSavingAccount : ISavingAccount

{

private float balance;

public FixDepositSavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public bool CanWithdraw(float amount)

{

throw new Exception("Not supported by this account type");

}

}

public class AccountManager

{

public static void WithdrawFromAccount(ISavingAccount account, float amount)

{

try

{

if (account.CanWithdraw(amount))

Console.WriteLine("Can withdraw");

else

Console.WriteLine("Cannot withdraw");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine("Error: " + ex.Message);

}

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

float initialBalance = 10000f;

float withdrawalAmount = 5000f;

//works ok

AccountManager.WithdrawFromAccount(new RegularSavingAccount(initialBalance), withdrawalAmount);

//works ok

AccountManager.WithdrawFromAccount(new SalarySavingAccount(initialBalance), withdrawalAmount);

//throws exception as withdrawal is not supported

AccountManager.WithdrawFromAccount(new FixDepositSavingAccount(initialBalance), withdrawalAmount);

}

}In this example, the implementation is not following the Liskov Substitution Principle because FixDepositSavingAccount is modifying the functionality of the CanWithdraw() method

To avoid this, LSP can be applied to produce the following alternative:

using System;

public interface ISavingAccount

{

}

public abstract class SavingAccountWithWithdrawal : ISavingAccount

{

public abstract bool CanWithdraw(float amount);

}

public abstract class SavingAccountWithoutWithdrawal : ISavingAccount

{

}

public class RegularSavingAccount : SavingAccountWithWithdrawal

{

private float balance;

public RegularSavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public override bool CanWithdraw(float amount)

{

float moneyAfterWithdrawal = balance - amount;

if (moneyAfterWithdrawal >= 1000)

{

return true;

}

else

return false;

}

}

public class SalarySavingAccount : SavingAccountWithWithdrawal

{

private float balance;

public SalarySavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

public override bool CanWithdraw(float amount)

{

float moneyAfterWithdrawal = balance - amount;

if (moneyAfterWithdrawal >= 0)

{

return true;

}

else

return false;

}

}

public class FixDepositSavingAccount : SavingAccountWithoutWithdrawal

{

private float balance;

public FixDepositSavingAccount(float initialBalance)

{

this.balance = initialBalance;

}

}

public class AccountManager

{

public static void WithdrawFromAccount(SavingAccountWithWithdrawal account, float amount)

{

try

{

if (account.CanWithdraw(amount))

Console.WriteLine("Can withdraw");

else

Console.WriteLine("Cannot withdraw");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine("Error: " + ex.Message);

}

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

float initialBalance = 10000f;

float withdrawalAmount = 5000f;

//works ok

AccountManager.WithdrawFromAccount(new RegularSavingAccount(initialBalance), withdrawalAmount);

//works ok

AccountManager.WithdrawFromAccount(new SalarySavingAccount(initialBalance), withdrawalAmount);

//compiler gives error

AccountManager.WithdrawFromAccount(new FixDepositSavingAccount(initialBalance), withdrawalAmount);

}

}After these changes, FixDepositSavingAccount is no longer able to produce unexpected behaviour, since it is constrained at compile-time. This now satifies LSP.

A client should not be forced to depend on methods it does not use.

A sub-class should not be forced to implement methods it does not use.

The Interface Segregation Principle approaches a similar problem to that tackled by LSP, in that it is aimed at preventing code behaving in an unexpected manner.

In the case of LSP, the principle states that sub-classes should behave as expected based on their super-class.

In the case of ISP, the principle states that sub-classes should not be forced to implement methods that they do not use (which could again result in unexpected behaviour).

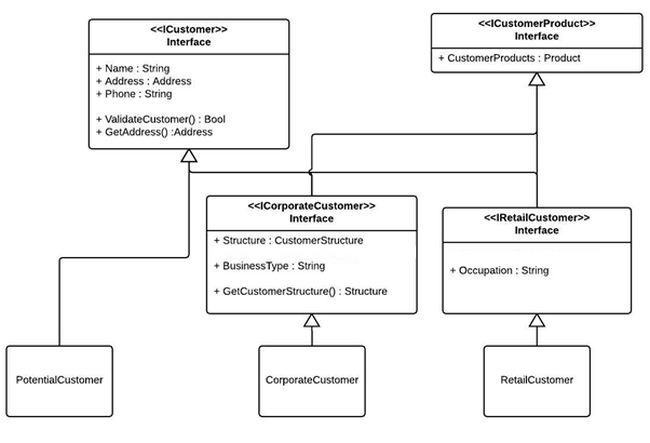

To satisfy ISP, it is better to implement many small interfaces rather than a one big interface.

A real-world example for ISP would be a dustbin:

- A single general dustbin will end up with a mixture of different garbage types, which will make it hard to recycle.

- Using several type-specific dustbins (e.g. paper, glass, metal) will make it much easier to recycle.

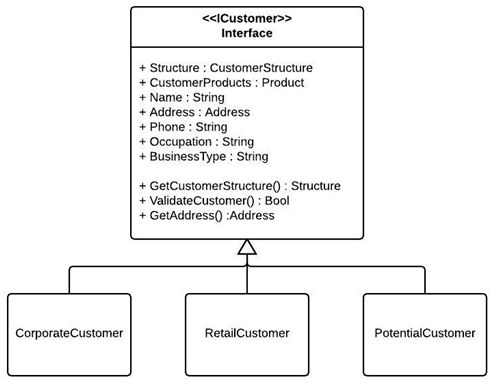

For a code example, consider the case of a bank with the following types of customers:

- Corporate customer: For corporate people.

- Retail customer: For individual, daily banking.

- Potential customer: They are just a bank customer that does not yet hold a product of the bank and it is just a record that is different from corporate and retail.

The developer of a system defines the following interface for a customer:

Note that this interface forces the client class to implement methods that are not required, which violates ISP:

- A potential customer, who does not yet hold any product, is forced to implement a CustomerProducts property.

- A potential customer and a retail customer are both forced to have a CustomerStructure property, which only applies to a corporate customer.

- A potential customer and a retail customer are both forced to implement a BusinessType, which only applies to a corporate customer.

- A corporate customer and a potential customer are both forced to implement an Occupation property, which only applies to a retail customer.

In a case such as this, the solution is to split the interface into smaller, more targeted parts, such as in the following example:

Entities must depend on abstractions not on concretions.

A high level module should not depend on a low level module; they should both depend on abstractions.

Extending this principle leads to the Dependency Injection (DI) pattern.

DIP is demonstrated in the following example:

First, the responsibility we want to abstract out is defined and made public. The concrete implementation(s) of this responsibility can then be instantiated using a public factory class.

namespace MyNamespace.Dependency

{

public interface ICustomerDataAccess

{

string GetCustomerName(int id);

}

internal class CustomerDataAccess: ICustomerDataAccess

{

public CustomerDataAccess()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id) {

return "Dummy Customer Name";

}

}

public class DataAccessFactory

{

public static ICustomerDataAccess GetCustomerDataAccessObj()

{

return new CustomerDataAccess();

}

}

}The abstracted responsibility can then be referenced by a consumer without the consumer needing to be aware of the details:

using System;

using MyNamespace.Dependency;

namespace MyNamespace.Consumer

{

public class CustomerBusinessLogic

{

ICustomerDataAccess _custDataAccess;

public CustomerBusinessLogic()

{

_custDataAccess = DataAccessFactory.GetCustomerDataAccessObj();

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _custDataAccess.GetCustomerName(id);

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

CustomerBusinessLogic customerBL = new CustomerBusinessLogic();

Console.WriteLine(customerBL.GetCustomerName(123));

}

}

}

Any responsibility that is not the main responsibility of the class should not be encapsulated in the class, and should not be a direct dependency of the class.

Achieved using Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP), and the Dependency Injection (DI) and Strategy patterns.

IoC is a design principle which recommends the inversion of different kinds of controls in object-oriented design to achieve loose coupling between application classes. It is closely related to the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP).

In this case, control refers to any additional responsibilities a class has, other than its main responsibility, such as control over the flow of an application, or control over the dependent object creation and binding.

The goal is that any responsibility that is not the main responsibility of the class should not be encapsulated in the class, and should not be a direct dependency of the class.

This is achieved using the Dependency Injection (DI) and Strategy patterns.

Adopting IoC is a prerequisite of TDD.

Secondary responsibilities are injected into a class, to avoid direct dependencies or unnecessary encapsulation.

Constructor Injection, Property Injection & Method Injection.

A refinement of DI is the Strategy pattern (ability to select algorithm at run-time)

The Dependency Injection is a pattern used to implement IoC (Inversion of Control), which allows for loosely coupled classes.

The pattern involves 3 types of classes:

- Client Class: The client class (dependent class) is a class which depends on the service class

- Service Class: The service class (dependency) is a class that provides service to the client class.

- Injector Class: The injector class injects the service class object into the client class.

There are three types of Dependency Injection:

- Constructor Injection

- Property Injection

- Method Injection

Each is described below.

In each of the examples, the dependency (a.k.a. Service Class) to be injected is the following:

namespace MyNamespace.Dependency

{

// public interface defines dependency

public interface ICustomerDataAccess

{

string GetCustomerName(int id);

}

// INTERNAL SERVICE: concrete implementation of dependency

internal class CustomerDataAccess : ICustomerDataAccess

{

public CustomerDataAccess()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

//get the customer name from the db in real application

return "Dummy Customer Name";

}

}

}And the logic (a.k.a. Client Class) is consumed by the following:

using System;

using MyNamespace.Logic;

namespace MyNamespace.Consumer

{

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

CustomerService customerService = new CustomerService();

Console.WriteLine(customerService.GetCustomerName(123));

}

}

}Constructor Injection

using MyNamespace.Dependency;

namespace MyNamespace.Logic

{

// INTERNAL CLIENT

internal class CustomerBusinessLogic

{

ICustomerDataAccess _dataAccess;

// dependency is injected into constructor

public CustomerBusinessLogic(ICustomerDataAccess custDataAccess)

{

_dataAccess = custDataAccess;

}

public CustomerBusinessLogic()

{

_dataAccess = new CustomerDataAccess();

}

public string ProcessCustomerData(int id)

{

return _dataAccess.GetCustomerName(id);

}

}

// PUBLIC INJECTOR

public class CustomerService

{

CustomerBusinessLogic _customerBL;

public CustomerService()

{

// inject dependency via constructor

_customerBL = new CustomerBusinessLogic(new CustomerDataAccess());

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _customerBL.ProcessCustomerData(id);

}

}

}Property Injection

using MyNamespace.Dependency;

namespace MyNamespace.Logic

{

// INTERNAL CLIENT

internal class CustomerBusinessLogic

{

public CustomerBusinessLogic()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return DataAccess.GetCustomerName(id);

}

// dependency is injected into property

public ICustomerDataAccess DataAccess { get; set; }

}

// PUBLIC INJECTOR

public class CustomerService

{

CustomerBusinessLogic _customerBL;

public CustomerService()

{

_customerBL = new CustomerBusinessLogic();

// inject dependency via property

_customerBL.DataAccess = new CustomerDataAccess();

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _customerBL.GetCustomerName(id);

}

}

}Method Injection

using MyNamespace.Dependency;

namespace MyNamespace.Logic

{

// INTERNAL CLIENT

internal class CustomerBusinessLogic

{

ICustomerDataAccess _dataAccess;

public CustomerBusinessLogic()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _dataAccess.GetCustomerName(id);

}

// dependency is injected into method

public void SetDependency(ICustomerDataAccess customerDataAccess)

{

_dataAccess = customerDataAccess;

}

}

// PUBLIC INJECTOR

public class CustomerService

{

CustomerBusinessLogic _customerBL;

public CustomerService()

{

_customerBL = new CustomerBusinessLogic();

// inject dependency via method

_customerBL.SetDependency(new CustomerDataAccess());

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _customerBL.GetCustomerName(id);

}

}

}

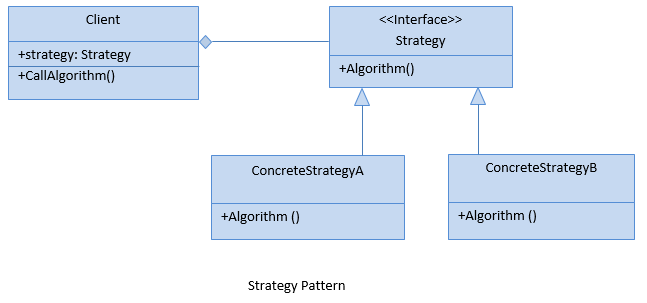

Allows algorithms to be selected at run-time.

The strategy pattern is intended to provide a means to define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one as an object, and make them interchangeable.

The strategy pattern lets the algorithms vary independently from clients that use them.

This is of particular relevance for the Dependency Injection pattern.

This pattern allows algorithms to be selected a run-time, so that algorithms can vary indepentently from the clients that use them.

The Strategy pattern is of particular use when combined with the Dependency Injection pattern.

Advantages

- More maintainable and readable (avoids switch, if, else...).

- Enables loose coupling between components.

- Easily extendable.

Disadvantages

- Clients must know of the existence of different strategies and must understand how the strategies differ.

- It increases the number of objects in the application.

Applicable When...*

This pattern is used when there are multiple similar classes that only differ in terms of how they execute the behavior. As mentioned, this is of particular relevance when combined with the Dependency Injection pattern (where algorithms are "injected" into a client).

Example: Accessing a Database

using System;

using MyNamespace.Dependency;

using MyNamespace.Logic;

namespace MyNamespace.Dependency

{

// public interface defines dependency

public interface ICustomerDataAccess

{

string GetCustomerName(int id);

}

// identifies different algorithm types

public enum DbAccessType

{

SQL,

REST

}

// instantiates the requested algorithm type

public class DataAccessFactory

{

public static ICustomerDataAccess GetCustomerDataAccessObj(DbAccessType dbAccessType)

{

ICustomerDataAccess customerDataAccess = null;

switch (dbAccessType)

{

case DbAccessType.SQL:

customerDataAccess = new CustomerDataAccessSQL();

break;

case DbAccessType.REST:

customerDataAccess = new CustomerDataAccessREST();

break;

default:

throw new Exception("unrecognized DB access type");

}

return customerDataAccess;

}

}

// algorithm 1

internal class CustomerDataAccessSQL : ICustomerDataAccess

{

public CustomerDataAccessSQL()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

//get the customer name from the db in real application

return "Dummy Customer Name using SQL";

}

}

// algorithm 2

internal class CustomerDataAccessREST : ICustomerDataAccess

{

public CustomerDataAccessREST()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

//get the customer name from the db in real application

return "Dummy Customer Name using REST";

}

}

}

namespace MyNamespace.Logic

{

// receives and processing results of database query

internal class CustomerBusinessLogic

{

ICustomerDataAccess _dataAccess;

public CustomerBusinessLogic()

{

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _dataAccess.GetCustomerName(id);

}

// dependency is injected into method

public void SetDependency(ICustomerDataAccess customerDataAccess)

{

_dataAccess = customerDataAccess;

}

}

// used by consumer to access the database using a particular type of algorithm

public class CustomerService

{

CustomerBusinessLogic _customerBL;

public CustomerService(DbAccessType dbAccessType)

{

_customerBL = new CustomerBusinessLogic();

// inject dependency via method

_customerBL.SetDependency(DataAccessFactory.GetCustomerDataAccessObj(dbAccessType));

}

public string GetCustomerName(int id)

{

return _customerBL.GetCustomerName(id);

}

}

}

namespace MyNamespace.Consumer

{

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

// NOTE: clients must be aware of the existance of the different DbAccessTypes,

// which is a downside of the strategy pattern

CustomerService customerServiceREST = new CustomerService(DbAccessType.REST);

Console.WriteLine(customerServiceREST.GetCustomerName(123));

CustomerService customerServiceSQL = new CustomerService(DbAccessType.SQL);

Console.WriteLine(customerServiceSQL.GetCustomerName(123));

}

}

}

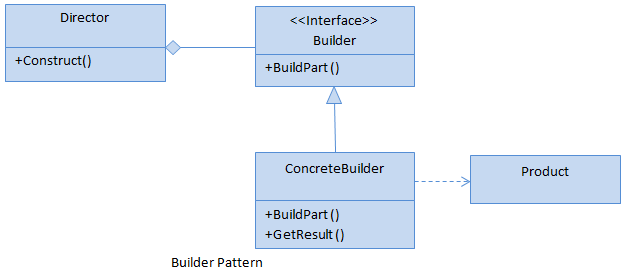

Separate the construction of a complex object from its representation so that the same construction process can create different representations.

Construct a complex object step by step and the final step returns the object.

Also, the process of constructing an object should be generic so that it can be used to create different representations of the same object.

Similar to Factory pattern, but more related to enabling clients to create different representations of the same object.

There are four main components to the Builder Pattern:

- Builder: defines all the steps required to create a product.

- ConcreteBuilder: implements or extends Builder.

- Product: defines the object to be created.

- Director: constructs an object using the Builder implementation.

Advantages

- More maintainable and readable

- Less prone to errors as we have a method which returns the finally constructed object.

Disadvantages

- Number of lines of code increases in builder pattern, but it makes sense as the effort pays off in terms of maintainability and readability.

Applicable When...

This pattern is chiefly of use when a constructor would otherwise have many arguments (particularly if some are optional).

Example: Creating Toys

using System;

using System.Text.Json;

// Defines the steps required to create a Toy

public interface IToyBuilder

{

void SetModel();

void SetHead();

void SetLimbs();

void SetBody();

void SetLegs();

Toy GetToy();

}

// Defines the object to be created

public class Toy

{

public string Model

{

get;

set;

}

public string Head

{

get;

set;

}

public string Limbs

{

get;

set;

}

public string Body

{

get;

set;

}

public string Legs

{

get;

set;

}

}

// Builds Toy Model A

public class ToyABuilder : IToyBuilder

{

Toy toy = new Toy();

public void SetModel()

{

toy.Model = "TOY A";

}

public void SetHead()

{

toy.Head = "1";

}

public void SetLimbs()

{

toy.Limbs = "4";

}

public void SetBody()

{

toy.Body = "Plastic";

}

public void SetLegs()

{

toy.Legs = "2";

}

public Toy GetToy()

{

return toy;

}

}

// Builds Toy Model B

public class ToyBBuilder : IToyBuilder

{

Toy toy = new Toy();

public void SetModel()

{

toy.Model = "TOY B";

}

public void SetHead()

{

toy.Head = "1";

}

public void SetLimbs()

{

toy.Limbs = "4";

}

public void SetBody()

{

toy.Body = "Steel";

}

public void SetLegs()

{

toy.Legs = "4";

}

public Toy GetToy()

{

return toy;

}

}

// Manages the constructor of a Toy

public class ToyCreator

{

private IToyBuilder _toyBuilder;

public ToyCreator(IToyBuilder toyBuilder)

{

_toyBuilder = toyBuilder;

}

public void CreateToy()

{

_toyBuilder.SetModel();

_toyBuilder.SetHead();

_toyBuilder.SetLimbs();

_toyBuilder.SetBody();

_toyBuilder.SetLegs();

}

public Toy GetToy()

{

return _toyBuilder.GetToy();

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

Console.WriteLine("-------------------------------List Of Toys--------------------------------------------");

var toyACreator = new ToyCreator(new ToyABuilder());

toyACreator.CreateToy();

Toy toyA = toyACreator.GetToy();

Console.WriteLine(JsonSerializer.Serialize(toyA));

var toyBCreator = new ToyCreator(new ToyBBuilder());

toyBCreator.CreateToy();

Toy toyB = toyBCreator.GetToy();

Console.WriteLine(JsonSerializer.Serialize(toyB));

}

}

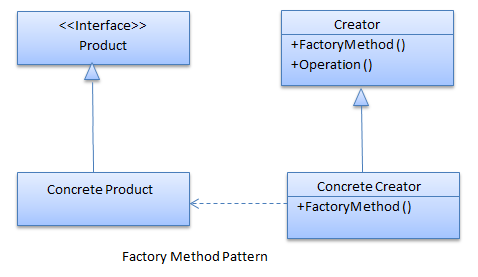

Allows classes to be created without client needing to know how to do it.

Similar to Builder pattern, but more related to enabling clients to create multiple different, but related, objects.

There are four main components to the Factory Method Pattern:

- Product: defines the the objects that factory method creates.

- ConcreteProduct: implements Product.

- Creator: declares the factory method (may also declare a default implementation).

- ConcreteCreator: implements or extends Creator and overrides the factory method to returns instances of ConcreteProduct.

Advantages

- Enables loose coupling between components.

- Easily extendable.

Disadvantages

- Clients must know of the existence of different factories and must understand how the factories differ.

- It increases the number of objects in the application.

Applicable When...

This pattern can be used whenever a client needs to create more than a single object.

Example: Creating Vehicles

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

// Defines the product

abstract class Vehicle

{

public abstract string Marque { get; }

public abstract string Model { get; }

}

// Defines a specific type of product

class Car : Vehicle

{

private string _marque;

private string _model;

public Car(string marque, string model)

{

_marque = marque;

_model = model;

}

public override string Marque

{

get { return _marque; }

}

public override string Model

{

get { return _model; }

}

}

// Defines a specific type of product

class MotorCycle : Vehicle

{

private string _marque;

private string _model;

public MotorCycle(string marque, string model)

{

_marque = marque;

_model = model;

}

public override string Marque

{

get { return _marque; }

}

public override string Model

{

get { return _model; }

}

}

// Defines the factory method

abstract class VehicleFactory

{

public abstract Vehicle GetVehicle();

}

// Defines the factory for a specific product type

class CarFactory : VehicleFactory

{

private string _marque;

private string _model;

public CarFactory(string marque, string model)

{

_marque = marque;

_model = model;

}

public override Vehicle GetVehicle()

{

return new Car(_marque, _model);

}

}

// Defines the factory for a specific product type

class MotorCycleFactory : VehicleFactory

{

private string _marque;

private string _model;

public MotorCycleFactory(string marque, string model)

{

_marque = marque;

_model = model;

}

public override Vehicle GetVehicle()

{

return new MotorCycle(_marque, _model);

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

VehicleFactory factory = null;

string vehicleType = "car";

switch (vehicleType.ToLower())

{

case "car":

factory = new CarFactory("Honda", "Civic");

break;

case "motorcycle":

factory = new MotorCycleFactory("Honda", "VFR800F");

break;

default:

break;

}

Vehicle vehicle = factory.GetVehicle();

Console.WriteLine("\nYour vehicle details are below : \n");

Console.WriteLine($"Marque: {vehicle.Marque}\nModel: {vehicle.Model}");

}

}

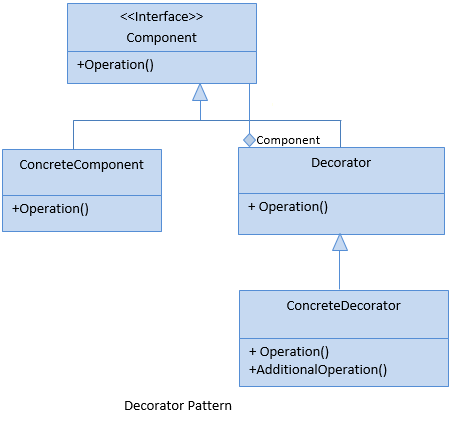

An alternative to sub-classing for extending functionality dynamically.

Wrap components to override or extend functionality.

The idea of the Decorator Pattern is to wrap an existing class, add other functionality to it, then expose the same interface to the outside world. Because of this our decorator exactly looks like the original class to the people who are using it.

It is used to extend or alter the functionality at run-time. It does this by wrapping them in an object of the decorator class without modifying the original object. So it can be called a wrapper pattern.

There are four components to the Decorator Pattern:

- Component: defines the existing API for the object that needs to be extended.

- ConcreteComponent: implements or extends Component and defines the object to be extended.

- Decorator: defines all of the functionalities that can be added to ConcreteComponent.

- ConcreteDecorator: implements ONE of the functionaties that need to be added to ConcreteComponent.

Advantages

- Adds functionality to existing objects dynamically

- Alternative to sub-classing

- Flexible design

- Supports Open-Closed Principle

Disadvantages

- Number of lines of code increases in builder pattern, but it makes sense as the effort pays off in terms of maintainability and readability.

Applicable When...

This pattern is particularly of use in the following situations:

- Adding functionality to a legacy system.

- Adding functionality to a control.

- Adding functionality to sealed classes.

Example 1: Aggregating Features & Cost

using System;

// Component: defines the functionality

public interface ICar

{

string GetDescription();

double GetCost();

}

// ConcreteComponent: defines an object that implements Component

public class EconomyCar : ICar

{

public string GetDescription()

{

return "Economy Car";

}

public double GetCost()

{

return 450000.0;

}

}

// ConcreteComponent: defines another object that implements Component

public class DeluxeCar : ICar

{

public string GetDescription()

{

return "Deluxe Car";

}

public double GetCost()

{

return 750000.0;

}

}

// ConcreteComponent: defines another object that implements Component

public class LuxuryCar : ICar

{

public string GetDescription()

{

return "Luxury Car";

}

public double GetCost()

{

return 1000000.0;

}

}

// Decorator: Defines the decorator wrapper than overrides or extends the Component functionality.

public abstract class CarAccessoriesDecorator : ICar

{

private ICar _car;

public CarAccessoriesDecorator(ICar aCar)

{

this._car = aCar;

}

public virtual string GetDescription()

{

return this._car.GetDescription();

}

public virtual double GetCost()

{

return this._car.GetCost();

}

}

// ConcreteDecorator: Overrides the Component functionality.

public class BasicAccessories : CarAccessoriesDecorator

{

public BasicAccessories(ICar aCar)

: base(aCar)

{

}

public override string GetDescription()

{

return base.GetDescription() + ", Basic Accessories Package";

}

public override double GetCost()

{

return base.GetCost() + 2000.0;

}

}

// ConcreteDecorator: Overrides the Component functionality.

public class AdvancedAccessories : CarAccessoriesDecorator

{

public AdvancedAccessories(ICar aCar)

: base(aCar)

{

}

public override string GetDescription()

{

return base.GetDescription() + ", Advanced Accessories Package";

}

public override double GetCost()

{

return base.GetCost() + 10000.0;

}

}

// ConcreteDecorator: Overrides or extends the Component functionality.

public class SportsAccessories : CarAccessoriesDecorator

{

public SportsAccessories(ICar aCar)

: base(aCar)

{

}

public override string GetDescription()

{

return base.GetDescription() + ", Sports Accessories Package";

}

public override double GetCost()

{

return base.GetCost() + 15000.0;

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

// Create EcomomyCar instance.

ICar objCar = new EconomyCar();

// Wrap EconomyCar instance with BasicAccessories.

CarAccessoriesDecorator objAccessoriesDecorator = new BasicAccessories(objCar);

// Wrap EconomyCar instance with AdvancedAccessories instance.

objAccessoriesDecorator = new AdvancedAccessories(objAccessoriesDecorator);

Console.WriteLine("Car Details: " + objAccessoriesDecorator.GetDescription());

Console.WriteLine("Total Price: " + objAccessoriesDecorator.GetCost());

}

}Example 2: Maintaining an Audit Trail

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

// Component: defines the base functionality

abstract class RestaurantDish

{

public abstract void Display();

}

// ConcreteComponent: defines an object that implements Component

class FreshSalad : RestaurantDish

{

private string _greens;

private string _cheese; //I am going to use this pun everywhere I can

private string _dressing;

public FreshSalad(string greens, string cheese, string dressing)

{

_greens = greens;

_cheese = cheese;

_dressing = dressing;

}

public override void Display()

{

Console.WriteLine("\nFresh Salad:");

Console.WriteLine(" Greens: {0}", _greens);

Console.WriteLine(" Cheese: {0}", _cheese);

Console.WriteLine(" Dressing: {0}", _dressing);

}

}

// ConcreteComponent: defines another object that implements Component

class Pasta : RestaurantDish

{

private string _pastaType;

private string _sauce;

public Pasta(string pastaType, string sauce)

{

_pastaType = pastaType;

_sauce = sauce;

}

public override void Display()

{

Console.WriteLine("\nClassic Pasta:");

Console.WriteLine(" Pasta: {0}", _pastaType);

Console.WriteLine(" Sauce: {0}", _sauce);

}

}

// Decorator: Defines the decorator wrapper than overrides or extends the Component functionality.

abstract class Decorator : RestaurantDish

{

protected RestaurantDish _dish;

public Decorator(RestaurantDish dish)

{

_dish = dish;

}

public override void Display()

{

_dish.Display();

}

}

// ConcreteDecorator: Extends the Component functionality.

class Available : Decorator

{

public int NumAvailable { get; set; } //How many can we make?

protected List<string> customers = new List<string>();

public Available(RestaurantDish dish, int numAvailable) : base(dish)

{

NumAvailable = numAvailable;

}

public void OrderItem(string name)

{

if (NumAvailable > 0)

{

customers.Add(name);

NumAvailable--;

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine("\nNot enough ingredients for " + name + "'s order!");

}

}

public override void Display()

{

base.Display();

foreach (var customer in customers)

{

Console.WriteLine("Ordered by " + customer);

}

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

//Step 1: Define some dishes, and how many of each we can make

FreshSalad caesarSalad = new FreshSalad("Crisp romaine lettuce", "Freshly-grated Parmesan cheese", "House-made Caesar dressing");

caesarSalad.Display();

Pasta fettuccineAlfredo = new Pasta("Fresh-made daily pasta", "Creamly garlic alfredo sauce");

fettuccineAlfredo.Display();

Console.WriteLine("\nMaking these dishes available.");

//Step 2: Decorate the dishes; now if we attempt to order them once we're out of ingredients, we can notify the customer

Available caesarAvailable = new Available(caesarSalad, 3);

Available alfredoAvailable = new Available(fettuccineAlfredo, 4);

//Step 3: Order a bunch of dishes

caesarAvailable.OrderItem("John");

caesarAvailable.OrderItem("Sally");

caesarAvailable.OrderItem("Manush");

alfredoAvailable.OrderItem("Sally");

alfredoAvailable.OrderItem("Francis");

alfredoAvailable.OrderItem("Venkat");

alfredoAvailable.OrderItem("Diana");

alfredoAvailable.OrderItem("Dennis"); //There won't be enough for this order.

caesarAvailable.Display();

alfredoAvailable.Display();

}

}

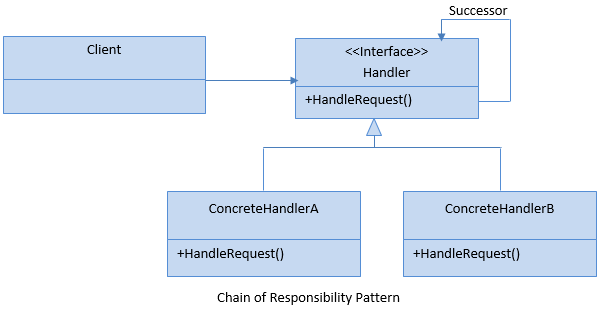

Used when one of many callers might take action on an object (e.g. a chain of approvals).

Each actor is represented by a handler, for which there is a successor.

There are four components to the Chain of Responsibility Pattern:

- Client: generates the request and passes it to the first Handler.

- Handler: Defines the actor and includes a member that holds the next Handler.

- ConcreteHandlerA/ConcreteHandlerB: each Handler implementation contains functionality to handle some request and then pass responsibility to the next in the chain.

Advantages

- Avoids coupling the sender to the receiver.

Disadvantages

- ?

Applicable When...

Some cases when this pattern is useful:

- Seeking approvals (Team Lead > Project Lead > Delivery Manager > Director)

- Triaging issues (Level > Level 1 > Level 2 > Level 3)

Try/catch statements are also an example of this.

Example: ATM Machine

using System;

public abstract class Handler

{

public Handler nextHandler;

public void NextHandler(Handler moneyHandler)

{

this.nextHandler = moneyHandler;

}

public abstract void DispatchMoney(long requestedAmount);

protected void outputMoney(long requestedAmount, long divisor, string handlerName)

{

long numberofNotesToBeDispatched = requestedAmount / divisor;

if (numberofNotesToBeDispatched > 0)

{

string notes = numberofNotesToBeDispatched > 1 ? "notes are" : "note is";

Console.WriteLine($"{numberofNotesToBeDispatched} x {divisor} {notes} dispatched by {handlerName}");

}

long pendingAmountToBeProcessed = requestedAmount % divisor;

if (pendingAmountToBeProcessed > 0)

nextHandler.DispatchMoney(pendingAmountToBeProcessed);

}

}

public class TwoThousandHandler : Handler

{

public override void DispatchMoney(long requestedAmount)

{

outputMoney(requestedAmount, 2000, "TwoThousandHandler");

}

}

public class FiveHundredHandler : Handler

{

public override void DispatchMoney(long requestedAmount)

{

outputMoney(requestedAmount, 500, "FiveHundredHandler");

}

}

public class TwoHundredHandler : Handler

{

public override void DispatchMoney(long requestedAmount)

{

outputMoney(requestedAmount, 200, "TwoHundredHandler");

}

}

public class HundredHandler : Handler

{

public override void DispatchMoney(long requestedAmount)

{

outputMoney(requestedAmount, 100, "HundredHandler");

}

}

public class ATM

{

private TwoThousandHandler twoThousandHandler = new TwoThousandHandler();

private FiveHundredHandler fiveHundredHandler = new FiveHundredHandler();

private TwoHundredHandler twoHundredHandler = new TwoHundredHandler();

private HundredHandler hundredHandler = new HundredHandler();

public ATM()

{

// Prepare the chain of Handlers

twoThousandHandler.NextHandler(fiveHundredHandler);

fiveHundredHandler.NextHandler(twoHundredHandler);

twoHundredHandler.NextHandler(hundredHandler);

}

public void Withdraw(long requestedAmount)

{

twoThousandHandler.DispatchMoney(requestedAmount);

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

ATM atm = new ATM();

Console.WriteLine("\n Requested Amount 4600");

atm.Withdraw(4600);

Console.WriteLine("\n Requested Amount 1900");

atm.Withdraw(1900);

Console.WriteLine("\n Requested Amount 600");

atm.Withdraw(600);

}

}

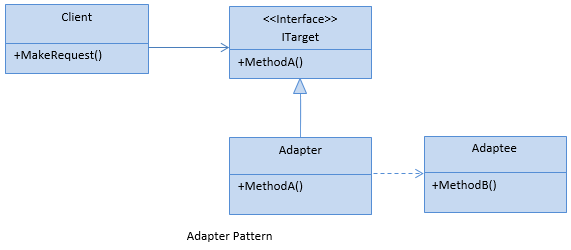

Allows communication between two incompatible interfaces by acting as a bridge.

This pattern involves a single class called adapter which is responsible for communication between two independent or incompatible interfaces.

There are four main components to the Adapter Pattern:

- ITarget: defines the request the client wants to make.

- Adapter: implements ITarget and inherits the Adaptee class, and translates the request for the incompatible code.

- Adaptee: contains the incompatible code.

- Client: wants to access the incompatible code.

Advantages

- More maintainable and readable

- Supports the Open-Closed Principle (can add new adapters without disturbing existing client logic)

- Less prone to errors as we have a method which returns the finally constructed object.

Disadvantages

- Number of lines of code increases in the Adapter pattern, but it makes sense as the effort pays off in terms of maintainability and readability.

Applicable When...

This is typically used when a new system needs to communicate with an existing, independent system.

Example

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

// Define the request that the Client wishes to make

public interface ITarget

{

List<string> GetResponses();

}

// Translate the client's request to a form the adaptee understands

public class Adapter : ITarget

{

public List<string> GetResponses()

{

return new ResponsesStore().GetResponsesRecieved();

}

}

// The adaptee

public class ResponsesStore

{

public List<string> GetResponsesRecieved()

{

var responses = new List<string>() {

"This is a test response by user 1",

"This is a test response by user 2",

"This is a test response by user 3",

"This is a test response by user 4"

};

return responses;

}

}

// The client

public class Client

{

private ITarget _target;

public Client(ITarget target)

{

_target = target;

}

public List<string> GetResponsesRecieved()

{

return _target.GetResponses();

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

var client = new Client(new Adapter());

var userResponses = client.GetResponsesRecieved();

userResponses.ForEach(p => Console.WriteLine(p));

}

}

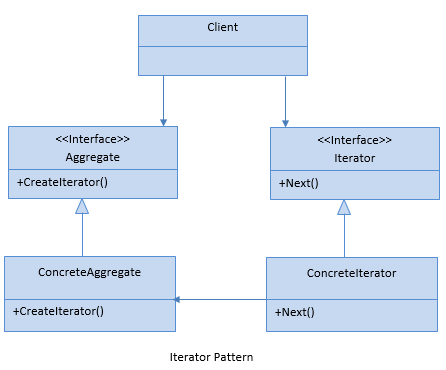

Iterator Design Pattern provides a way to access the elements of a collection object in a sequential manner without knowing its underlying structure.

The basic Iterator API allows a client to try to get the next object in a collection.

There are five components to this pattern:

- Client: the class that contains a collection of objects, each of which can be retrieved using a Next operation.

- Iterator: defines operators for accessing the collection elements in sequence.

- ConcreteIterator: implements or extends Iterator.

- Aggregate: defines an operation to create an Iterator.

- ConcreteAggregate: implements of extends Aggregate.

IEnumerable implementations are an example of this.

Advantages

- Client doesn't need to worry about implementation details of accessing a collection.

Disadvantages

- ????

Applicable When...

- Allows accessing the elements of a collection object in a sequential manner without knowing its underlying structure.

- Multiple or concurrent iterations are required over collections elements.

- Provides a uniform interface for accessing the collection elements.

Example

using System;

using System.Collections;

// the client wishes to access a collection of objects

public class CollectionProcessor

{

private IterableCollection collection;

public CollectionProcessor()

{

// client has access to a collection

this.collection = new IterableCollection();

this.collection.Add("One");

this.collection.Add("Two");

this.collection.Add("Three");

this.collection.Add("Four");

this.collection.Add("Five");

}

// client iterates over contents of collection

public void ProcessCollection()

{

Iterator iterator = collection.CreateIterator();

while (iterator.Next())

{

string item = (string)iterator.Current;

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

}

}

// defines a collection that provides an Iterator to itself

public interface IIterableCollection

{

Iterator CreateIterator();

}

// a collection that provides an Iterator to itself

public class IterableCollection : IIterableCollection

{

private ArrayList items = new ArrayList();

public Iterator CreateIterator()

{

return new ConcreteIterator(this);

}

public object this[int index]

{

get { return items[index]; }

}

public int Count

{

get { return items.Count; }

}

public void Add(object o)

{

items.Add(o);

}

}

// defines operators for accessing elements of a collection

public interface Iterator

{

object Current { get; }

bool Next();

}