The Ethernaut is a Web3/Solidity based wargame inspired from overthewire.org, played in the Ethereum Virtual Machine. Each level is a smart contract that needs to be 'hacked'.

Level 1: Fallback

Level 2: Fallout

Level 3: Coin Flip

Level 4: Telephone

Level 5: Token

Level 6: Delegation

Level 7: Force

Level 8: Vault

Level 9: King

Level 10: Re-entrancy

Level 11: Elevator

Level 12: Privacy

Level 13: Gatekeeper One

Level 14: Gatekeeper Two

Level 15: Naught Coin

Level 16: Preservation

Level 17: Recovery

Level 18: Magic Number

Level 19: Denial

Level 20: Alien Codex

Level 21: Shop

- Clone repository

- Install dependencies:

npm i - Compile contracts:

oz compile - Deploy your ethernaut instance level using metamask

- Create a

.envfile and define your INFURA_KEY, MNEMONIC, and ACCOUNT environment variables. - Execute individual level hack:

node attacks/[level].js

Target: claim ownership of the contract & reduce its balance to 0.

The contract's fallback function can owneship of the contract. The conditional requirements are not secure: any contributor can become owner after sending any value to the contract.

Solidity concept: fallback function

A contract can have at most one fallback function, declared using fallback () external [payable] (without the function keyword). This function cannot have arguments, cannot return anything and must have external visibility. It is executed on a call to the contract if none of the other functions match the given function signature, or if no data was supplied at all and there is no receive Ether function. The fallback function always receives data, but in order to also receive Ether it must be marked payable. Like any function, the fallback function can execute complex operations as long as there is enough gas passed on to it.

- Contribute

- Send any amount to the contract, which will trigger the fallback.

- Conditional requirements will be met

- Sender becomes the owner

- Be careful when implementing a fallback that changes state as it can be triggered by anyone sending ETH to the contract.

- Avoid writing a fallback that can perform critical actions such as changing ownership or transfer funds.

- A common pattern is to let the fallback only emit events (e.g emit FundsReceived).

Target: claim ownership of the contract.

The contract used a syntax deprecated since v 0.5. The function meant to be the constructor isn't one. It can actually be called after contract initialisation. It has a public visibility and can be called by anyone.

Solidity Concept: constructor

A constructor is an optional function declared with the constructor keyword which is executed upon contract creation, and where you can run contract initialisation code. Before the constructor code is executed, state variables are initialised to their specified value if you initialise them inline, or zero if you do not. Prior to version 0.4.22, constructors were defined as functions with the same name as the contract. This syntax was deprecated and is not allowed anymore in version 0.5.0.

The Fal1out() function was supposed to be named Fallout() and would have been the contract's constructor as syntax previous version 0.5.

Simply call the Fal1out() function.

- Work with the latest compiler versions which are more secure.

- Listen to the compiler warnings.

- Do test driven development to detect typos.

Target: guess the correct outcome 10 times in a row.

The contract tries to create randomness by relying on blockhashes, block number and a given FACTOR. This data isn't secret:

blockhash()andblock.numberare global variables in solidity- the

FACTORused to compute thecoinFlipvalue can be reused by the attacker

blockhash(uint blockNumber) returns (bytes32): hash of the given block - only works for 256 most recent blocks

block.number (uint): current block number

Deploy an attacker contract.

- Attacker contract compute the

blockValueby using theblock.numberandblockhash()global variables. - As

FACTORis known, the attacker contract can next computecoinFlipandside. - Pass the right

sideargument to the originalflipfunction that we call from the attacker contract.

There’s no true randomness on Ethereum blockchain, only "pseudo-randomness" i.e. random generators that are considered “good enough”.

There currently isn't a native way to generate true randomness in the EVM.

Everything used in smart contracts is publicly visible, including the local variables and state variables marked as private.

Miners also have control over things like blockhashes, timestamps, and whether to include certain transactions - which allows them to bias these values in their favor.

Target: claim ownership of the contract.

A conditional requirements uses tx.origin

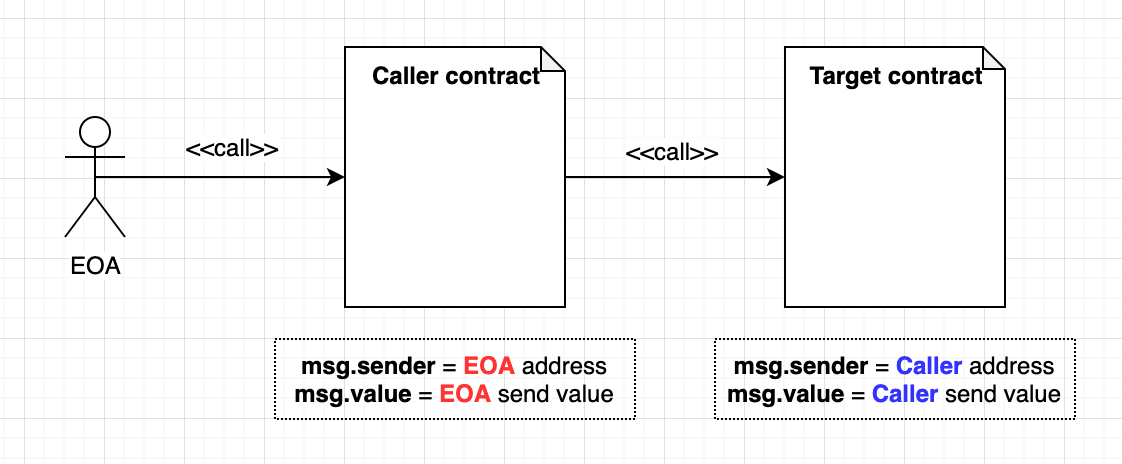

Solidity Concepts: tx.origin vs msg.sender

tx.origin (address payable): sender of the transaction (full call chain)msg.sender (address payable): sender of the message (current call)

In the situation where a user call a function in contract 1, that will call function of contract 2:

| at execution contract 1 | at execution in contract 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| msg.sender | userAddress | contract1Address |

| tx.origin | userAddress | userAddress |

Deploy an attacker contract.

Call the changeOwner function of the original contract from the attacker contract to ensure tx.origin != msg.sender and pass the conditional requirement.

Target: You are given 20 tokens to start with and you will beat the level if you somehow manage to get your hands on any additional tokens. Preferably a very large amount of tokens.

An sum operation is performed but overflow isn't checked for.

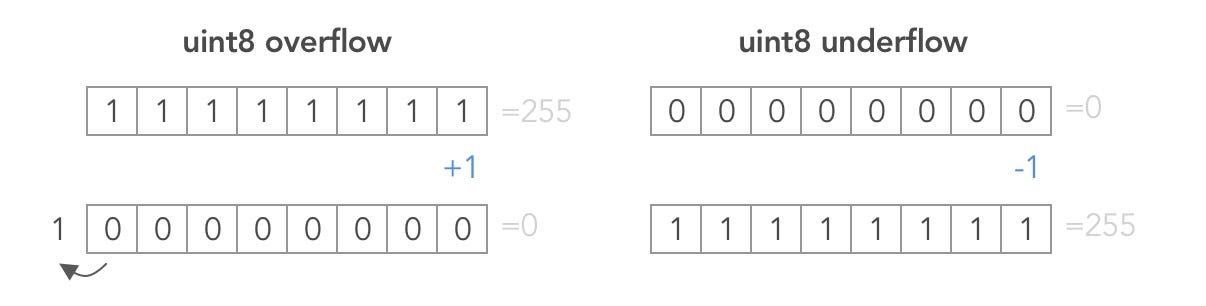

Solidity Concepts: bits storage, underflow/overflow

Ethereum’s smart contract storage slots are each 256 bits, or 32 bytes.

Solidity supports both signed integers, and unsigned integers uint of up to 256 bits.

However as in many programming languages, Solidity’s integer types are not actually integers. They resemble integers when the values are small, but behave differently if the numbers are larger. For example, the following is true: uint8(255) + uint8(1) == 0. This situation is called an overflow. It occurs when an operation is performed that requires a fixed size variable to store a number (or piece of data) that is outside the range of the variable’s data type. An underflow is the converse situation: uint8(0) - uint8(1) == 255.

Provoke the overflow by transferring 21 tokens to the contract.

Reducing the player's balance will indeed overflow: 20 - 21 -> overflow

Check for over/underflow manually:

if(a + c > a) {

a = a + c;

}

Or use OpenZeppelin's math library that automatically checks for overflows in all the mathematical operators.

Target: claim ownership of the contract.

The Delegation fallback implements a delegatecall.

By sending the right msg.data we can trigger the function pwn() of the Delegate contract.

Since this function is executed by a delegatecall the context will be preserved:

owner = msg.sender = address of contract that send data to the Delegation fallback (attacker contract)

There are several ways to interact with other contracts from within a given contract.

If the ABI (like an API for smart contract) and the contract's address are known, we can simply instantiate (e.g with a contract interface) the contract and call its functions).

contract Called {

function fun() public returns (bool);

}

contract Caller {

Called public called;

constructor (Called addr) public {

called = addr;

}

function call () {

called.fun();

}

}

Calling a function means injecting a specific context (arguments) to a group of commands (function) and commands are executing one by one with this context.

In Ethereum, a function call can be expressed by a 2 parts bytecode as long as 4 + 32 * N bytes.

- Function Selector: first 4 bytes of function call’s bytecode.

Generated by hashing target function’s name plus with the type of its arguments

excluding empty space. Ethereum uses keccak-256 hashing function to create function selector:

functionSelectorHash = web3.utils.keccak256('func()') - Function Argument: convert each value of arguments into a hex string padded to 32bytes.

If there is more than one argument, they are concatenated.

In Solidity encoding the function selector together with the arguments can be done with abi.encode, abi.encodePacked, abi.encodeWithSelector and abi.encodeWithSignature:

abi.encodeWithSignature("add(uint256,uint256)", valueForArg1, valueForArg2)

Can be used to invoke public functions by sending data in a transaction.

contractInstance.call(bytes4(keccak256("functionName(inputType)"))

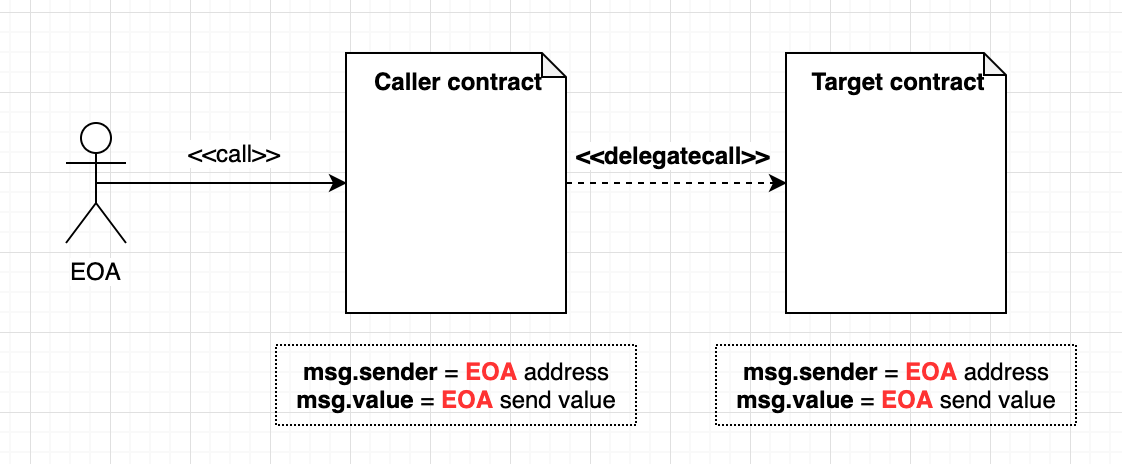

DelegateCall: preserves context

contractInstance.delegatecall(bytes4(keccak256("functionName(inputType)"))

Delegate calls preserve current calling contract's context (storage, msg.sender, msg.value).

The calling contract using delegate calls allows the called contract to mutate its state.

- Compute the encoded hash that will be used for

msg.data - Send

msg.datain a transaction to the contract fallback

- Use the higher level call() function to inherit from libraries, especially when you don’t need to change contract storage and do not care about gas control.

- When inheriting from a library intending to alter your contract’s storage, make sure to line up your storage slots with the library’s storage slots to avoid unexpected state changes..

- Authenticate and do conditional checks on functions that invoke delegatecalls.

Target: make the balance of the contract greater than zero.

Solidity Concept: selfdestruct

3 methods exist to receive Ethers:

- Message calls and payable functions

addr.call{value: x}(''): returns success condition and return data, forwards all available gas, adjustable<address payable>.transfer(uint256 amount): reverts on failure, forwards 2300 gas stipend, not adjustable<address payable>.send(uint256 amount) returns (bool): returns false on failure, forwards 2300 gas stipend, not adjustable

function receive() payable external {}

- contract designated as recipient for mining rewards

selfdestruct(address payable recipient): destroy the current contract, sending its funds to the given Address and end execution.

As the contract to hack has no payable function to receive ether, we send ether to it by selfdestructing another contract, designating the victim contract as the recipient.

By selfdestructing a contract, it is possible to send ether to another contract even if it doesn't have any payable functions. This is dangerous as it can result in losing ether: sending ETH to a contract without withdraw function, or to a removed contract.

Target: Unlock Vault contract.

The unlock function relies on a password with a private visibility.

There is no real privacy on Ethereum which is public blockchain.

The private visibility parameter is misleading as all data can still be read.

Indeed the contract is available, so an attacker can know in which storage slot a variable is stored in and access its value manually using getStorageAt.

- storage: persistent data between function calls and transactions.

- Key-value store that maps 256-bit words to 256-bit words.

- Not possible to enumerate storage from within a contract

- Costly to read, and even more to initialise and modify storage. Because of this cost, you should minimize what you store in persistent storage to what the contract needs to run. Store data like derived calculations, caching, and aggregates outside of the contract.

- A contract can neither read nor write to any storage apart from its own.

- memory ~ RAM: not persistent. A contract obtains a freshly cleared instance of memory for each message call

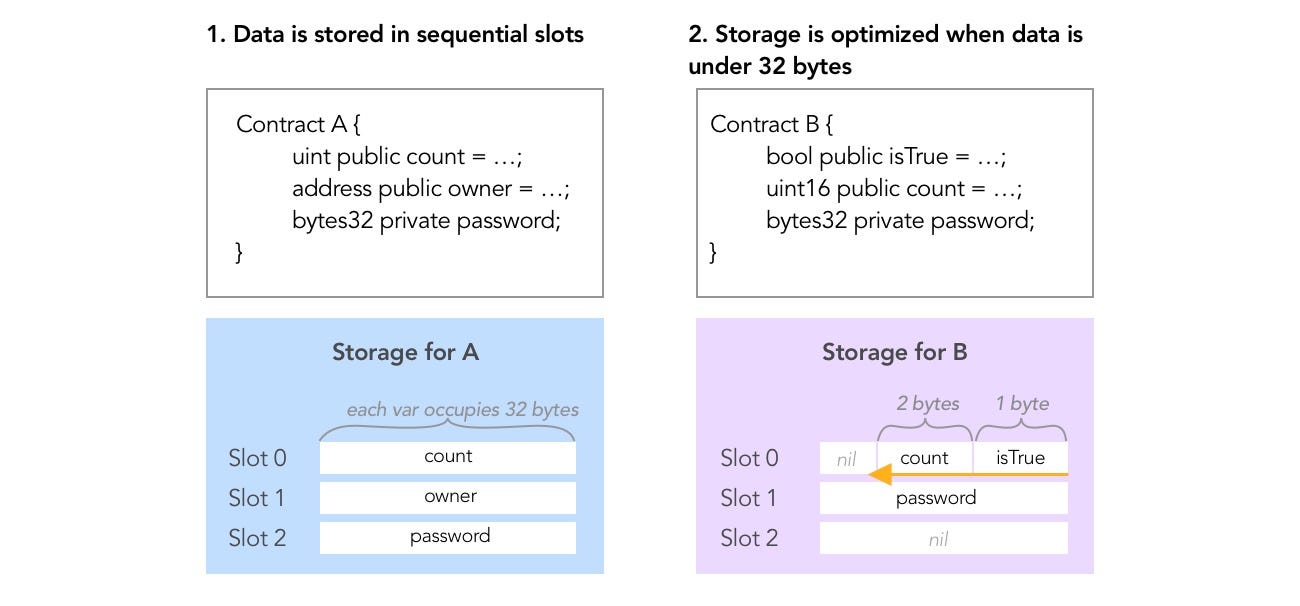

Data stored is storage in laid out in slots according to these rules:

- Each slot allows 32 bytes = 256 bits

- Slots start at index 0

- Variables are indexed in the order they’re defined in contract

contract Sample {

uint256 first; // slot 0

uint256 second; // slot 1

}

- Bytes are being used starting from the right of the slot

- If a variable takes under < 256 bits to represent, leftover space will be shared with following variables if they fit in this same slot.

- If a variable does not fit the remaining part of a storage slot, it is moved to the next storage slot.

- Structs and arrays (non elementary types) always start a new slot and occupy whole slots (but items inside a struct or array are packed tightly according to these rules).

- Constants don’t use this type of storage. (They don't occupy storage slots)

Read storage: web3.eth.getStorageAt

Knowing a contract's address and the storage slot position a variable is stored in, it is possible to read its value value using the getStorageAt function of web3.js.

- Read contract to find out in slot

passwordis stored in:lockedbool takes 1 bit of the first slot index 0passwordis 32 bytes long. It can fit on the first slot so it goes on next slot at index 1

- Read storage at index 1

- Pass this value to the unlock function

- Nothing is private in the EVMhttps://solidity.readthedocs.io/en/v0.6.2/security-considerations.html#private-information-and-randomness: addresses, timestamps, state changes and storage are publicly visible.

- Even if a contract set a storage variable as

private, it is possible to read its value withgetStorageAt - When necessary to store sensitive value onchain, hash it first (e.g with sha256)

Target: Prevent losing kingship when submitting your contract instance.

The contract uses transfer instead of a withdraw pattern to send Ether.

Solidity Concepts: sending and receiving Eth

- Neither contracts nor “external accounts” are currently able to prevent that someone sends them Ether. Contracts can react on and reject a regular transfer

- If a contract receives Ether (without a function being called), either the receive Ether or the fallback function is executed. If it does not have a receive nor a fallback function, the Ether will be rejected (by throwing an exception).

Upon submission, the level contract sends an Ether amount higher than prize to the contract instance contract fallback to reclaim kingship. The fallback uses transfer to send the prize value to the current king which about to be replace. Only then the king address is updated. If the current king is a contract without a fallback or receive function execution will fail before the king address can be updated.

- Deploy a malicious contract without neither a payable fallback nor a payable receive function

- Let this malicious contract become king by sending Ether to the vKing contract

- Submit instance

- Assume any external account or contract you don't know/own is potentially malicious

- Never assume transactions to external contracts will be successful

- Handle failed transactions on the client side in the event you do depend on transaction success to execute other core logic.

Especially when transferring ETH:

- Avoid using

send()ortransfer(). If usingsend()check returned value - Prefer a 'withdraw' pattern to send ETH

Target: steal all funds from the contract.

Similarly to the attack in the level 7, when sending directly funds to an address, one does not now if it is an POA or a contract, and how the contract the contract will handle the funds. The fallback could "reenter" in the function that triggered it. If the check effect interaction pattern is not followed, one could withdraw all the funds of a contract: e.g if a mapping that lists the users' balance is updated only at the end at the function!

Solidity Concepts: "reenter", calling back the contract that initiated the transaction and execute the same function again.

Check also the differences between call, send and transfer seen in level 7.

Especially by using call(), gas is forwarded, so the effect would be to reenter multiple times until the gas is exhausted.

- Deploy an attacker contract

- Implement a payable fallback that "reenter" in the victim contract: the fallback calls

reentrance.withdraw() - Donate an amount

donation - "Reenter" by withdrawing

donation: callreentrance.withdraw(donation)from attacker contract - Read

remainingbalance of victim contract:remaining = reentrance.balance - Withdraw

remaining: callreentrance.withdraw(remaining)from attacker contract

To protect smart contracts against re-entrancy attacks, it used to be recommended to use transfer() instead of send or call as it limits the gas forwarded. However gas costs are subject to change. Especially with EIP 1884 gas price changed.

So smart contracts logic should not depend on gas costs as it can potentially break contracts.

transfer does depend on gas costs (forwards 2300 gas stipend, not adjustable), therefore it is no longer recommended: Source 1 Source 2

Use call instead. As it forwards all the gas, execution of smart contracts won't break.

But if we use call and don't limit gas anymore to prevent ourselves from errors caused by running out of gas, we are then exposed to re-entrancy attacks, aren't we?!

This is why one must:

- Respect the check-effect-interaction pattern.

- Perform checks

- who called?

msg.sender == ? - how much is send?

msg.value == ? - Are arguments in range

- Other conditions...

- who called?

- If checks are passed, perform effects to state variables

- Interact with other contracts or addresses

- external contract function calls

- send ethers ...

- Perform checks

- or use a use a re-entrancy guard: a modifier that checks for the value of a

lockedbool

Target: reach the top of the Building.

The Elevator never implements the isLastFloor() function from the Building interface. An attacker can create a contract that implements this function as it pleases him.

Solidity Concepts: interfaces & inheritance

Interfaces are similar to abstract contracts, but they cannot have any functions implemented. Contracts need to be marked as abstract when at least one of their functions is not implemented.

Contract Interfaces specifies the WHAT but not the HOW. Interfaces allow different contract classes to talk to each other. They force contracts to communicate in the same language/data structure. However interfaces do not prescribe the logic inside the functions, leaving the developer to implement it. Interfaces are often used for token contracts. Different contracts can then work with the same language to handle the tokens.

Interfaces are also often used in conjunction with Inheritance.

When a contract inherits from other contracts, only a single contract is created on the blockchain, and the code from all the base contracts is compiled into the created contract. Derived contracts can access all non-private members including internal functions and state variables. These cannot be accessed externally via

this, though. They cannot inherit from other contracts but they can inherit from other interfaces.

- Write a malicious attacker contract that will implement the

isLastFloorfunction of theBuildinginterface - implement

isLastFloorNote thatisLastFlooris called 2 times ingoTo. The first time it has to returnTrue, but the second time it has to returnFalse - invoke

goTo()from the malicious contract so that the malicious version of theisLastFloorfunction is used in the context of our level’s Elevator instance!

Interfaces guarantee a shared language but not contract security. Just because another contract uses the same interface, doesn’t mean it will behave in the same way.

Target: unlock contract.

Similarly to the Level 8 -Vault, the contract's security relies on the value of a variable defined as private. This variable is actually publicy visible

The layout of storage data in slots and how to read data from storage with getStorageAt were covered in Level 8 -Vault.

The slots are 32 bytes long.

1 byte = 8 bits = 4 nibbles = 4 hexadecimal digits.

In practice, when using e.g getStorageAt we get string hashes of length 64 + 2 ('0x') = 66.

- Analyse storage layout: |slot|variable| |--|--| |0|bool (1 bit long)| |1|ID (256 bits long)| |2|awkwardness (16 bytes) - denomination (8 bytes) - flattening (8 bytes)| |3|data[0] (32 bytes long)| |4|data[1] (32 bytes long)| |5|data[2] (32 bytes long)|

The _key variable is slot 5.

2. Take the first 16 bytes of the get: take the first 2 ('0x') + 2 * 16 = 34 characters of the bytestring.

- Same as for Level 8 -Vault:

- All storage is publicly visible, even

privatevariables - Don't store passwords or secret data on chain without hashing them first

- All storage is publicly visible, even

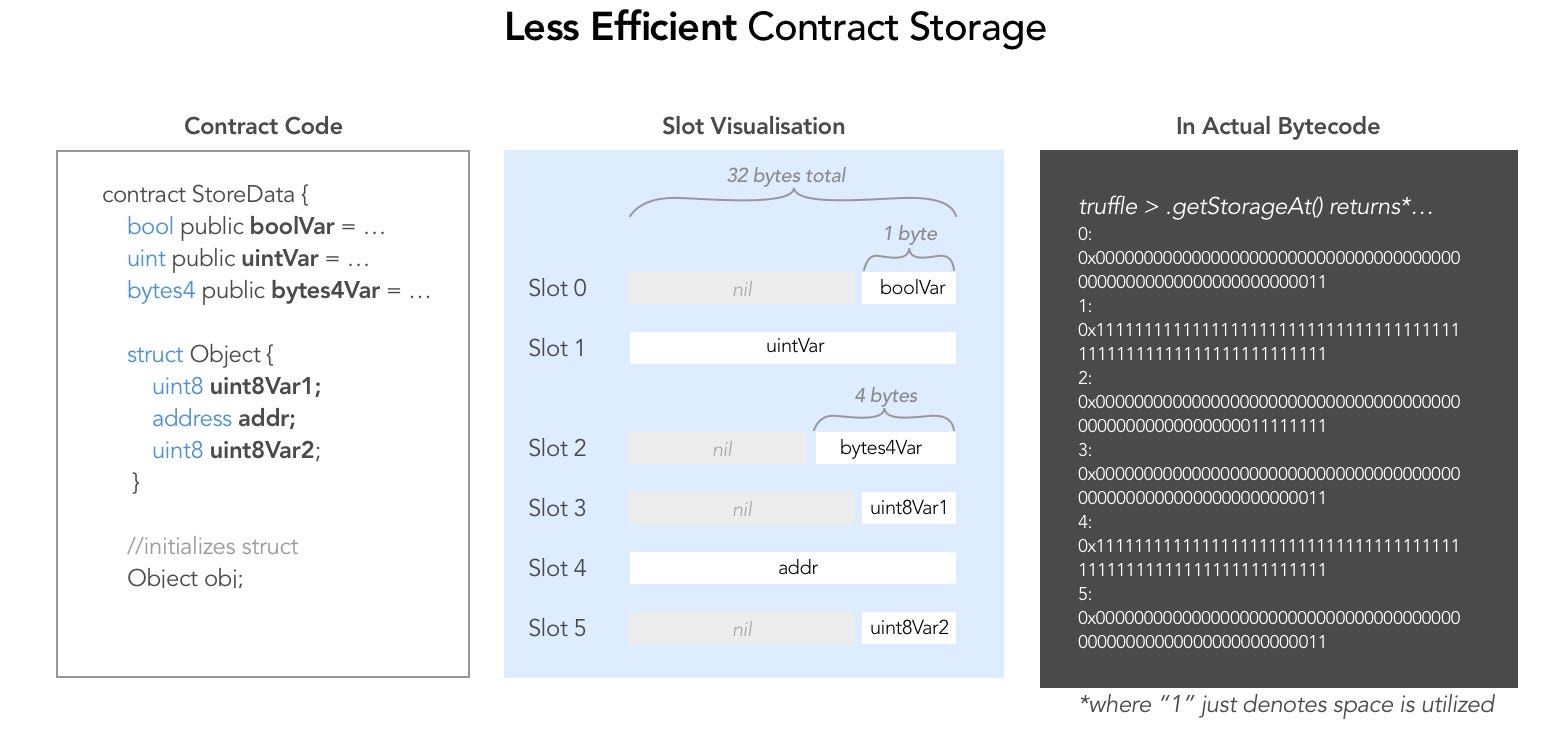

- Storage optimization

- Use

memoryinstead of storage if persisting data in state is not necessary - Order variables in such way that slots occupdation is maximized.

- Use

Target: make it past the gatekeeper one.

- Contract relies on

tx.origin. -

- Being able to read the public contract logic teaches how to pass gateTwo and gateThree.

Solidity Concepts: explicit conversions and masking

Be careful, conversion of integers and bytes behave differently!

| conversion to | uint | bytes |

|---|---|---|

| shorter type | left-truncate: uint8(273 = 0000 0001 0001 0001) = 00001 0001 = 17 |

right-truncate: bytes4(0x1111111122222222) = 0x11111111 |

| larger type | left-padded with 0: uint16(17 = 0001 0001) = 0000 0000 0001 0001 = 17 |

right-padded with 0: bytes8(0x11111111) = 0x1111111100000000 |

Masking means using a particular sequence of bits to turn some bits of another sequence "on" or "off" via a bitwise operation.

For example to "mask off" part of a sequence, we perform an AND bitwise operation with:

0for the bits to mask1for the bits to keep

10101010

AND 00001111

= 00001010

- Pass

gateOne: deploy an attacker contract that will call the victim contract'senterfunction to ensuremsg.sender != tx.origin. This is similar to what we've accomplished for the Level 4 - Telephone - Pass

gateTwo - Pass

gateThreeNote that we need to pass a 8 bytes long_gateKey. It is then explicitly converted to a 64 bits long integer.- Part one

uint16(uint64(_gateKey)): uint64 gateKey is converted to a shorter type (uint16) so we keep the last 16 bits of gateKey.uint32(uint64(gateKey)): uint64 gateKey is converted to a shorter type (uint32) so we keep the last 32 bits of gateKeyuint32(uint64(gateKey)) == uint16(uint64(gateKey)): we convert uint16 to a larger type (uint32), so we pad the last 16 bits of gateKey with 16*0 on the left. This concatenation should equal the last 32 bits of gateKey.- Mask to apply on the last 32 bits of gateKey:

0000 0000 0000 0000 1111 1111 1111 1111 = 0x0000FFFF

- Part two

uint32(uint64(gateKey): last 32 bits of gateKeyuint32(uint64(gateKey)) != uint64(_gateKey): the last 32 bits of gateKey are converted to a larger type (uint64), so we pad them with 320 on the left. This concanetation (320-last32bitsofGateKey) should not equal gateKey: so we need to keep the first bits of gateKey- Mask to apply to keep the first 32 bits:

0xFFFFFFFF

- Part one

- We then concatenate both masks:

0xFFFF FFFF 0000 FFFFRequires keeping the first 32 bits, mask with 0xFFFFFFFF. Concatenated with the first part: mask = 0xFFFF FFFF 0000 FFFF 3. Part three:uint32(uint64(gateKey)) == uint16(tx.origin)- we need to take gatekey = tx.origin

- we then apply the mask on tx.origin to ensure part one and two are correct

- Abstain from asserting gas consumption in your smart contracts, as different compiler settings will yield different results.

- Be careful about data corruption when converting data types into different sizes.

- Save gas by not storing unnecessary values.

- Save gas by using appropriate modifiers to get functions calls for free, i.e. external pure or external view function calls are free!

- Save gas by masking values (less operations), rather than typecasting

Target: make through the gatekeeper two

- gateOne relies on

tx.origin. - Being able to reading the public contract logic teaches how to pass gateTwo and gateThree.

Solidity Concepts: inline assembly & contract creation/initialization

From the Ethereum yellow paper section 7.1 - subtleties we learn:

while the initialisation code is executing, the newly created address exists but with no intrinsic body code⁴. 4. During initialization code execution, EXTCODESIZE on the address should return zero [...]

- gateOne: similar to the gateOne of Level 13 - Gatekeeper One or to the hack of Level 4 - Telephone

- gateTwo: call the

enterfunction during contract initialization, i.e from withinconstructorto ensureEXTCODESIZE = 0 - gateThree

uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) ^ uint64(_gateKey)noteda ^ bmeansa XOR buint64(0) - 1: underflow, this is equals touint64(1)

So we need to take_gatekey = ~a(Bitwise NOT) to ensure that the XOR product of each bit ofaandbwill be 1.

During contract initialization, the contract has no intrinsic body code and its extcodesize is 0.

Target: transfer your naughtcoins to another address.

NaughCoin inherits from the ERC20 contract.

Looking at this contract, we notice that transfer() is not the only function to transfer tokens.

Indeed transferFrom(address sender, address recipient, uint256 amount) can be used instead: provided that a 3rd user (spender) was allowed beforehand by the owner of the tokens to spend a given amount of the total owner's balance, spender can transfer amount to recipient in the name of owner.

Successfully executing transferFrom requires the caller to have allowance for sender's tokens of at least amount. The allowance can be set with the approve or increaseAllowance functions inherited from ERC20.

Concepts: ERC20 token contract

The ERC20 token contract is related to the EIP 20 - ERC20 token standard. It is the most widespread token standard for fungible assets.

Any one token is exactly equal to any other token; no tokens have special rights or behavior associated with them. This makes ERC20 tokens useful for things like a medium of exchange currency, voting rights, staking, and more.

transferFrom calls _transfer and _approve. _approve calls allowance and checks whether the caller was allowed to spend the amount by sender.

We want to set the player's allowance for the attack contract. For this we need to callapprove() which calls _approve(msg.sender, spender, amount). In this call we need msg.sender == player, so we can't call victim.approve() from the attacker contract. If we would, then msg.sender == attackerContractAddress. This would set the attacker contract's allowance instead of the player's one. So we call victim.approve() directly from the player's address.

Finally we let the attacker call transferFrom() to transfer to itself the player's tokens.

Get familiar with contracts you didn't write, especially with imported and inherited contracts. Check how they implement authorization controls.

Target

This contract utilizes a library to store two different times for two different timezones. The constructor creates two instances of the library for each time to be stored. The goal of this level is for you to claim ownership of the instance you are given.

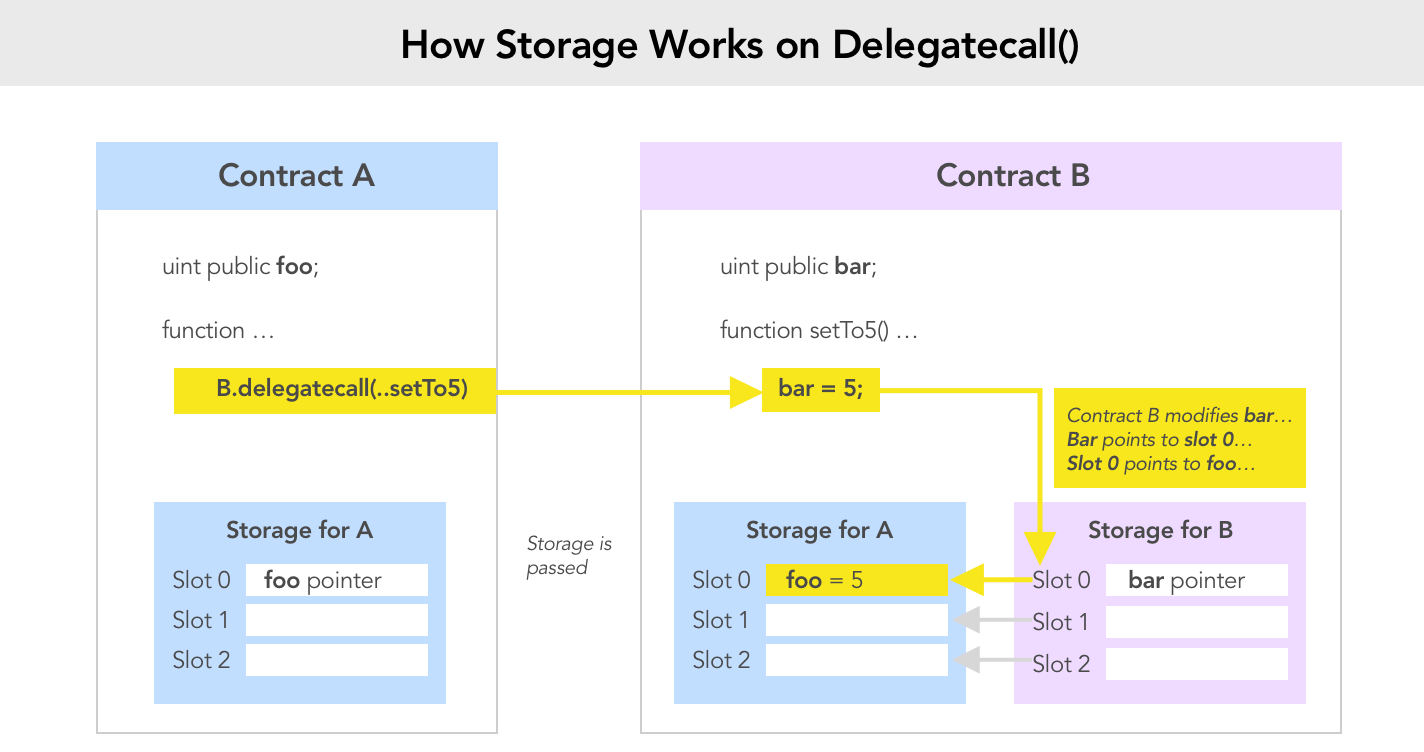

Preservationuses Libraries: Libraries usedelegatecalls. [Level 6 -Delegation] taught us that usingdelegatecallis risky as it allows the called contract to modifiy the storage of the calling contract.- Storage layouts of

PreservationandLibraryContractdon't match: Calling the library won't modifiy the expectedstoredTimevariable.

Solidity Concept: libraries

Libraries are similar to contracts, but their purpose is that they are deployed only once at a specific address and their code is reused using the DELEGATECALL (CALLCODE until Homestead) feature of the EVM. This means that if library functions are called, their code is executed in the context of the calling contract, i.e. this points to the calling contract, and especially the storage from the calling contract can be accessed.

So Libraries are a particular case where functions are on purpose called with delegatecall because preserving context is desired.

As libraries use delegatecall, they can modify the storage of Preservation.

LibraryContract can modify the first slot (index 0) of Preservation, which is address public timeZone1Library. So we can "set" timeZone1Library by calling setFirstTime(_timeStamp). The uint _timeStamp passed will converted to an address type though. It means we can cause setFirstTime() to execute a delegatecall from a library address different from the one defined at initialization. We need to define this malicious library so that its setTime function modifies the slot where owner is stored: slot of index 2.

Target

A contract creator has built a very simple token factory contract. Anyone can create new tokens with ease. After deploying the first token contract, the creator sent 0.5 ether to obtain more tokens. They have since lost the contract address. This level will be completed if you can recover (or remove) the 0.5 ether from the lost contract address.

The generation of contract addresses are pre-deterministic and can be guessed in advance.

- selfdestruct: see [Level 7 - Force] Sefdestruct is a method tha can be used to send ETH to a recipient upon destruction of a contract.

- encodeFunctionCall

At Level 6 - Delegation, we learnt how to make function call even though we don't know the ABI: by sending a raw transaction to a contract and passing the function signature into the data argument. More convenienttly, this can be done with the encodeFunctionCall function of web3.js:

web3.eth.abi.encodeFunctionCall(jsonInterface, parameters) - generation of contract addresses, from the Etherem yellow paper, section 7 - contract creation:

So in JavaScript, using the web3.js and rlp libraries, one can compute the contract address generated upon creation as follows.

// Rightmost 160 digits means rightmost 160 / 4 = 40 hexadecimals characters

contractAddress = '0x' + web3.utils.sha3(RLP.encode([creatorAddress, nonce])).slice(-40))

- Instantiate level. This will create 2 contracts:

- nonce 0:

Recoverycontract - nonce 1:

SimpleTokencontract

- nonce 0:

- Compute the

addressof theSimpleToken:- sender = instance address

- nonce = 1

- Use

encodeFunctionCallto call thedestructfunction ofSimpleTokeninstance ataddress.

Contract addresses are deterministic and are calculated by keccack256(rlp([address, nonce])) where the address is the address of the contract (or ethereum address that created the transaction) and nonce is the number of contracts the spawning contract has created (or the transaction nonce, for regular transactions). Because of this, one can send ether to a pre-determined address (which has no private key) and later create a contract at that address which recovers the ether. This is a non-intuitive and somewhat secretive way to (dangerously) store ether without holding a private key. An interesting blog post by Martin Swende details potential use cases of this.

Target

provide the Ethernaut with a "Solver", a contract that responds to "whatIsTheMeaningOfLife()" with the right number.

Smart contracts run on the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). The EVM understands smart contracts as bytecode. Bytecode is a sequence of hexadecimal characters:

0x6080604052348015600f57600080fd5b5069602a60005260206000f3600052600a6016f3fe.

Developers on the other hand, write and read them using a more human readable format: solidity files.

The solidity compiler digests .sol files to generate:

- contract creation bytecode: this is the smart contract format that the EVM understands

- assembly code: this is the bytecode as a sequence of opcodes. From a human point of view, it is less readable that Solidity code but more readable than bytecode.

- Application Binary Interface (ABI): this is like a customized interpret in a JSON format that tells applications (e.g a Dapp making function calls using web3.js) how to communicate with a specific deployed smart contract. It translates the application language (JavaScript) into bytecode that the EVM can understand and execute.

Contract creation bytecode contain 2 different pieces of bytecode:

- creation code: only executed at deployment. It tells the EVM to run the constructor to initialize the contract and to store the remaining runtime bytecode.

- runtime code: this is what lives on the blockchain at what Dapps, users will interact with.

EVM = Stack Machine

As a stack machine, the EVM functions according to the Last In First Out principle: the last item entered in memory will be the first one to be consumed for the next operation.

So an operation such as 1 + 2 * 3 will be written 3 2 * 1 + and will be executed by a stack machine as follows:

| Stack Level | Step 0 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | Step 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 2 | * | 6 | 1 | + | 7 |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 3 | 6 |

In addition to its stack component, the EVM has memory, which is like RAM in the sense that it is cleared at the end of each message call, and storage, which corresponds to data persisted between message calls.

How do we control the EVM? How do we tell it what to execute?

We have to give it a sequence of instructions in the form of OPCODES. An OPCODE can only push or consume items from the EVM’s stack, memory, or storage belonging to the contract.

Each OPCODE takes one byte.

Each OPCODE has a corresponding hexadecimal value: see the opcode values mapping here (from pyevm) or in the Ethereum Yellow Paper - appendix H.

So "assembling" the OPCODES hexadecimal values together means reconstructing the bytecode.

Splitting the bytecode into OPCODES bytes chunks means "disassembling" it.

For a more detailed guide on how to deconstruct a solidity code, check this post by Alejandro Santander in collaboration with Leo Arias.

-

Runtime code

# (bytes) OPCODE Stack (left to right = top to bottom) Meaning bytecode 00 PUSH1 2a push 2a (hexadecimal) = 42 (decimal) to the stack 602a 02 PUSH1 00 2a push 00 to the stack 6000 05 MSTORE 00, 2a mstore(0, 2a), store 2a = 42 at memory position 052 06 PUSH1 20 push 20 (hexadecimal) = 32 (decimal) to the stack (for 32 bytes of data) 6020 08 PUSH1 00 20 push 00 to the stack 6000 10 RETURN 00, 20 return(memory position, number of bytes), return 32 bytes stored in memory position 0f3

The assembly of these 10 bytes of OPCODES results in the following bytecode: 602a60005260206000f3

-

Creation code We want to excute the following:

mstore(0, 0x602a60005260206000f3): store the 10 bytes long bytecode in memory at position 0.

This will store602a60005260206000f3padded with 22 zeroes on the left to form a 32 bytes long bytestring.return(0x16, 0x0a): starting from byte 22, return the 10 bytes long runtime bytecode.

# (bytes) OPCODE Stack (left to right = top to bottom) Meaning bytecode 00 PUSH10 602a60005260206000f3 push the 10 bytes of runtime bytecode to the stack 69602a60005260206000f3 03 PUSH 00 602a60005260206000f3 push 0 to the stack 6000 05 MSTORE 0, 602a60005260206000f3 mstore(0, 0x602a60005260206000f3)052 06 PUSH a push a = 10 (decimal) to the stack 600a 08 PUSH 16 a push 16 = 22 (decimal) to the stack 6016 10 RETURN 16, a return(0x16, 0x0a)f3 -

The complete contract creation bytecode is then

69602a60005260206000f3600052600a6016f3 -

Deploy the contract with

web3.eth.sendTransaction({ data: '0x69602a60005260206000f3600052600a6016f3' }), which returns a Promise. The deployed contract address is the value of thecontractAddressproperty of the object returned when the Promise resolves. -

Pass the address of the deployed solver contract to the

setSolverfunction of theMagicNumbercontract.

Having an understanding of the EVM at a lower level, especially understanding how contracts are created and how bytecode can be dis/assembled from/to OPCODES is benefetial to smart contract developers in several ways:

- better debugging

- possibilities to finely optimize contract runtime or creation code

However both operations, assembling OPCODES into bytecode or disassembling bytecode into OPCODES, are cumbersome and tricky to manually perform without mistakes. So for efficiency and security reasons, developers are better off leaving it to compilers, writing solidity code and working with ABIs!

The Ethernaut is a Web3/Solidity based wargame inspired from overthewire.org, played in the Ethereum Virtual Machine. Each level is a smart contract that needs to be 'hacked'.

Target

This is a simple wallet that drips funds over time. You can withdraw the funds slowly by becoming a withdrawing partner. If you can deny the owner from withdrawing funds when they call withdraw() (whilst the contract still has funds) you will win this level.

The withdraw function uses call to send ETH to an unknown address. This poses two threats:

- Reentrancy (see Level 10 - Reentrancy: the recipient can implement a malicious fallback that will call back ('reenter') the

withdrawfunction - Out Of Gas (OOG) error:

callforwards all gas. The recipient may consume it all to prevent the execution of the following instructions.

Solidity Concepts: error handling

| expression | syntax | effect | OPCODE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| throw | if (condition) { throw; } |

reverts all state changes and deplete gas | version<0.4.1: INVALID OPCODE - 0xfe, after: REVERT- 0xfd | deprecated in version 0.4.13 and removed in version 0.5.0 |

| assert | assert(condition); |

reverts all state changes and depletes all gas | INVALID OPCODE - 0xfe | |

| revert | if (condition) { revert(value) } |

reverts all state changes, allows returning a value, refunds remaining gas to caller | REVERT - 0xfd | |

| require | require(condition, "comment") |

reverts all state changes, allows returning a value, refunds remaining gas to calle | REVERT - 0xfd |

So the main difference is that assert depletes all gas while revert and require don't. require is a less verbose version of revert.

When to use which error handling method? According to the solidity documentation

The assert function should only be used to test for internal errors, and to check invariants. Properly functioning code should never reach a failing assert statement; if this happens there is a bug in your contract which you should fix. The require function should be used to ensure valid conditions that cannot be detected until execution time. This includes conditions on inputs or return values from calls to external contracts.

We want to make the owner.transfer(amountToSend); instruction fail right after the partner.call.value(amountToSend)(""); instruction. As call forwards all gas, we will cause an Out Of Gas error.

- Deploy a malicious contract and set it as withdraw partner with

setWithdrawPartner - Cause an Out Of Gas Error by implementing a malicious fallback (that receive the ETH sent by the

partner.call.value(amountToSend)("")instruction)- Option 1: reenter in

denial.withdraw() - Option 2:

asserta false condition

- Option 1: reenter in

See Level 10 - Reentrancy takeaways.

Target: claim ownership of the contract

codex is stored as a dynamic array. retract() reduces codex length without checking against underflow. So it is actually possible to set the codex array length to 2²⁵⁶ -1, which gives power to modify all storage slots.

Solidity Concepts: storage layout of dynamically sized variables

Each smart contract running on the Ethereum Virtual Machine maintains its own state using a key:value storage mapping. The number possible of keys is so huge that most keys actually contain empty values. Each key is called a slot. They are 2²⁵⁶ - 1 slots. Each slot can contain 32 bytes of data.

In the Level 8 -Vault, I listed the basic storage layout rules. Each statically sized variable gets a reserved slot which is defined at compilation time.

But what about dynamically sized variables? As their size is not fixed beforehand, how to know which slots to reserve?

With regular hard drive space or RAM an allocation step to find free space to use exists, which is followed by a release step to put that space back into the pool of available storage. The number of storage locations of a smart contract is so huge that it manages its storage differently. It just needs to figure a way to define a storage location to start from. Indeed the likelihood of having location clashes is (not rigorously) 0.

Due to their unpredictable size, mapping and dynamically-sized array types use a Keccak-256 hash computation to find the starting position of the value or the array data. These starting positions are always full stack slots. For dynamic arrays, [the] slot stores the number of elements in the array (byte arrays and strings are an exception, see below). For mappings, the slot is unused (but it is needed so that two equal mappings after each other will use a different hash distribution). Array data is located at keccak256(p) and the value corresponding to a mapping key k is located at keccak256(k . p) where . is concatenation.

- Analyze storage layout

| Slot # | Variable |

|---|---|

| 0 | contact bool (1 bytes) & owner address (20 bytes), both fit on one slot |

| 1 | codex.length |

| keccak256(1) | codex[0] |

| keccak256(1) + 1 | codex[1] |

| ... | |

| 2²⁵⁶ - 1 | codex[2²⁵⁶ - 1 - uint(keccak256(1))] |

| 0 | codex[2²⁵⁶ - 1 - uint(keccak256(1)) + 1] --> can write slot 0! |

- call

make_contactto be able to pass thecontactedmodifer - call

retract: this provokes and underflow which leads tocode.length = 2^256 - 1 - Compute codex

indexcorresponding to slot 0:2²⁵⁶ - 1 - uint(keccak256(1)) + 1 = 2²⁵⁶ - uint(keccak256(1)) - Call

reversepassing itindexand your address left padded with 0 to total 32 bytes ascontent

Modifying a dynamic array length without checking for over/underflow is very dangerous as it can expand the array's bounds to the entire storage area of 2^256 - 1. This can possibly enable modifying the whole contract storage.

Target: get the item from the shop for less than the price asked.

Like for the Level 11 - Elevator, Shop never implements the price() function from the Buyer interface. An attacker can create a contract that implements its own version of this function.

When calling functions of other contracts, you can specify the amount of Wei or gas sent with the call with the special options .value() and .gas(), respectively.

buy() is calling price() twice:

- In the conditional check: the price returned must be higher than 100 to pass

- To update the price: here is the opportunity to return a value lower than 100.

So we need to implement a malicious price function that:

- returns a value higher than 100 on its first call

- returns a value lower than 100 on its second call

- costs less than 3000 gas to execute. So we can't write in storate. We will read

isSoldinstead to perform a conditinal check:isSold() ? 1: 101

- Don't let interface function unimplemented.

- It is unsafe to approve some action by double calling even the same view function.

Nicole Zhu.

I couldn't solve a couple of levels myself so I cheated a bit 😅 (especially for the Vault and Gatekeeper One levels).

Her walkthroughs are great teaching material on Solidity.

I also reused some of the diagram images from her posts.

Deconstructing a Solidity Contract —Part I: Introduction by Alejandro Santander from OpenZeppelin in collaboration with Leo Arias.