Elixir is a powerful and functional programming language designed for building scalable and maintainable applications. It's known for its concurrency model, fault-tolerance, and scalability.

- Elixir docs: https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/1.16/introduction.html

- Elixir Drops : https://www.youtube.com/@ElixirDrops

- Elixir Casts: https://www.youtube.com/@elixircasts2332

- Podcast : https://podcast.thinkingelixir.com/

- Books : https://elixir-lang.org/learning.html

- school : https://elixirschool.com/en

- LogRocket/Build rest api with phoenix

- Blog for RestAPI by: saswat.dev

- medium RestApi: without phoenix

- Rest API with Phoenix Bigginer level

-

Concurrency Model:

- Elixir runs on the Erlang Virtual Machine (BEAM), which is designed for building distributed and fault-tolerant systems.

- Processes in Elixir are lightweight and isolated, and they communicate through message passing.

-

Functional Programming:

- Elixir is a functional programming language, which means it emphasizes immutability and pure functions.Pattern matching, recursion, and higher-order functions are common in Elixir.

-

Immutable Data Structures:

- Elixir uses immutable data structures. Instead of modifying data in place, new data structures are created.This approach contributes to the overall stability of concurrent programs.

-

OTP (Open Telecom Platform):

- OTP is a set of libraries and design principles for building scalable and fault-tolerant systems.

- It includes features like supervisors for process management, gen_servers for building stateful processes, and more.

-

Pattern Matching:

- Elixir leverages pattern matching extensively. It's used in function heads, case statements, and more.

- It allows for concise and expressive code.

-

Mix:

- Mix is a build tool and package manager for Elixir projects. It helps you create, compile, and test projects.

- It also manages dependencies and provides tasks for common development workflows.

-

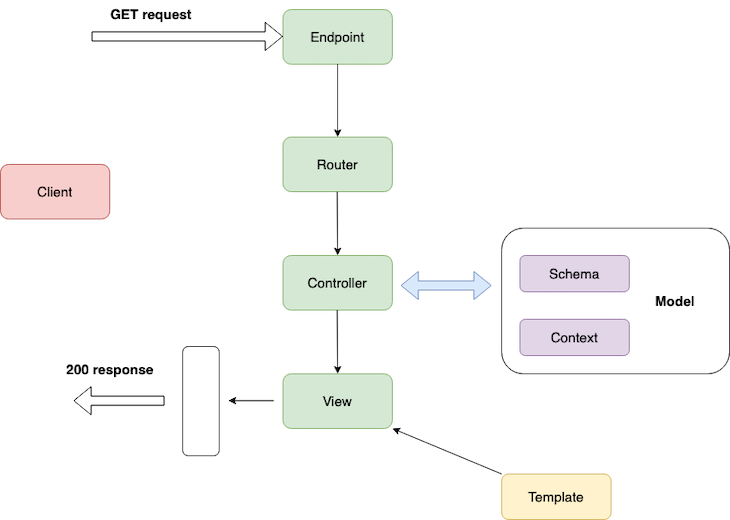

Phoenix Framework:

- Phoenix is a web framework for Elixir that makes it easy to build scalable and maintainable web applications.

- It follows the model-view-controller (MVC) pattern and includes features like channels for real-time communication.

-

Documentation:

- Elixir has a strong emphasis on documentation. You can generate and view documentation for your projects using ex_doc.

- iex : the interactive terminal of elixer which is used to debbug, compile and run commands like arithmetic logic 1 + 1.

- Link: https://hexdocs.pm/iex/1.15.7/IEx.html

- Elixir's interactive shell.

- Basics : https://elixirschool.com/en/lessons/basics/basics

- Getting Started

- Installing Elixir

- Trying Interactive Mode

- Basic Data Types

- Integers

- Floats

- Booleans

- Atoms

- Strings

- Basic Operations

- Arithmetic

- Boolean

- Comparison

- String Interpolation

- String Concatenation

- Getting Started

- Fucntions in Elixir : https://elixirschool.com/en/lessons/basics/functions

- Pattern matching (to be covered next week)

- Pattern matching

- tuples

- list

- operators

- module and functions

x = 1

1 = x

2 = xprice = 150

{product, ^price} = {"unga", 150}{"unga", 150}

price = 150

{product, ^price} = {"unga", 130}Pin oparator is used to reference an existing value/variable

a = 1

^a = 2academy = ["joyAnn", "dennis", "manasses"]["joyAnn", "dennis", "manasses"]

Destructure the list

[student1, student2, student3] = academy["joyAnn", "dennis", "manasses"]

student1"joyAnn"

Using Head and Tail the recursive nature in list

[head | tail] = academy

head"joyAnn"

tail["dennis", "manasses"]

Explain the following using the knowledge in pattern matching in list

[a, a] = [1, 1][1, 1]

[a, a] = [1, 2][a, a] = [2, 2][2, 2]

In Elixir, variables are immutable, which means that once a variable is assigned a value, it cannot be changed. Therefore, the statement [a, a] = [1, 1] will match the pattern and bind the variable a to the value 1. However, when you attempt [a, a] = [1, 2], it will raise a MatchError because the pattern [a, a] does not match the right-hand side [1, 2], where the values of a are different.

Maps can be created with the %{} syntax, and key-value pairs can be expressed as key => value: Example students

students = %{:name => ["michael", "joyAnn", "mobisa", "mongo"], :age => [27, 30, 24, 40]}%{name: ["michael", "joyAnn", "mobisa", "mongo"], age: [27, 30, 24, 40]}

students.name["michael", "joyAnn", "mobisa", "mongo"]

# accessing an atom in maps

students[:age]

# or

students.age[27, 30, 24, 40]

update students

updated_students = students |> Map.put_new(:Year, 2023)%{name: ["michael", "joyAnn", "mobisa", "mongo"], age: [27, 30, 24, 40], Year: 2023}

note how we have accessed the Year

updated_students[:Year]2023

Keys in maps can be accessed through some of the functions in this module (such as Map.get/3 or Map.fetch/2) or through the map[] syntax provided by the Access module:

map = %{a: 1, b: 2}

Map.fetch(map, :a)

{:ok, 1}

map[:b]

2

map["non_existing_key"]

nilwarning: code block contains unused literal 2 (remove the literal or assign it to _ to avoid warnings)

#cell:d3a5pki5x5ivsu6nrhul3xah4qfyfkc4:1

nil

To access atom keys, one may also use the map.key notation. Note that map.key will raise a KeyError if the map doesn't contain the key :key, compared to map[:key], that would return nil.

Note:

- The two syntaxes for accessing keys reveal the dual nature of maps. The map[key] syntax is used for dynamically created maps that may have any key, of any type.

- map.key is used with maps that hold a predetermined set of atoms keys, which are expected to always be present.

- Do not add parentheses when accessing fields, such as in data.key(). If parentheses are used, Elixir will expect data to be an atom representing a module and attempt to call the function key/0 in it.

Maps do not accept duplicate for exmple

laptop = %{brand: "Hp", storage: 500, brand: "Dell"}warning: key :brand will be overridden in map

#cell:hnybcvj5434zwgs3bx4elxan3iidrho3:1

%{brand: "Dell", storage: 500}

IO.puts(laptop.brand)

laptop.storageDell

500

person = %{name: "philip", age: 25, height: 6.5}%{name: "philip", age: 25, height: 6.5}

%{} = person%{name: "philip", age: 25, height: 6.5}

%{name: "philip", age: 25, height: 6.5, weight: 43} = personlistA = [1, 2, 3]

{:ok, total} = Enumerable.count(listA)

total3

- Structs built on the map syntax by passing the struct name between % and {. For example, %User{...}.

defmodule User do

defstruct name: "mike", age: 29

end{:module, User, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 8, ...>>, %User{name: "mike", age: 29}}

new_user = %User{name: "Josh", age: 25}%User{name: "Josh", age: 25}

IO.puts(new_user.age)

new_user.name25

"Josh"

In Elixir, the underscore (_) is used as a placeholder when you want to ignore a variable in a pattern match or when you're not interested in the value. It's often used as a convention to indicate that a particular value is intentionally being ignored.

# Example of a list

listB = [1, 2, 3, 4][1, 2, 3, 4]

[head | _] = listB

head1

# Example of Tuple

{a, _, c} = {1, 2, 3}{1, 2, 3}

a is bound to 1, c is bound to 3, and the second element is ignored

IO.puts(a)

c1

3

The underscore is a way to make your code more readable and to communicate to other developers (or to yourself) that a particular value is intentionally being disregarded in a given context. It also helps avoid compiler warnings about unused variables.

run this command

mix new your_project_nameThis creates a new folder named my_project containing a couple of subfolders and files. You can change to the my_project folder and compile the entire project:

make sure to follow elixir naming convention

$ cd my_project

$ mix compile

Compiling 1 file (.ex)

Generated my_project appThe compilation goes through all the files from the lib folder and places the resulting .beam files in the ebin folder.

You can execute various mix commands on the project. For example, the generator created the module MyProject with the single function hello/0. You can invoke it with mix run:

$ mix run -e "IO.puts(MyProject.hello())"

worldThe generator also create a couple of tests, which can be executed with mix test:

$ mix test

..

Finished in 0.03 seconds

2 tests, 0 failuresRegardless of how you start the mix project, it ensures that the ebin folder (where the .beam files are placed) is in the load path so the VM can find your modules.

https://elixirschool.com/en/lessons/basics/mix

- A specialized map with an identity for example

- Link : https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/1.16.0-rc.0/structs.html

%{}#map %identity{} #struct #new_user = %User{}

During definig values one can has default values i.e predefined keys

- After compilation you can only used the already named values

- it can have a custome name that has diff fields

NOTE: if you want a fixed structure structs are the go to, flexible maps are the go to

- To define a struct we use defstruct along with a keyword list of fields and default values:

defmodule Example.User do defstruct name: "Sean", roles: [] end

Note: defstruct can only be used once per module

defmodule User do

# defing a struct

# expects keys

defstruct [:name, :age]

# defstruct [name: "Miguel",age: 35] # keys with difault values

endnew_user = %User{name: "john doe", age: 49}

IO.puts(new_user.name)

IO.puts(new_user.age)john doe

49

:ok

defmodule User_B do

# defing a struct

# defstruct [:name, :age] #expects keys

# keys with difault values

defstruct name: "Miguel", age: 35

end{:module, User_B, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 8, ...>>, %User_B{name: "Miguel", age: 35}}

get_default = %User_B{}

IO.puts(get_default["name"])

IO.puts(get_default.age)new_user_b = %User_B{name: "Miguel joe", age: 46}

IO.puts(new_user_b.name)

IO.puts(new_user_b.age)Miguel joe

46

:ok

%{new_user_b | name: "smith", age: 29}%User_B{name: "smith", age: 29}

This explains the context of immutability and mutability

%User_B{gender: "male"}NOTE:

- The value is not strongly attached struct but the key is

- If you want to have fixed/immutabilty use maps

defmodule Person do

defstruct [:name, :age]

end{:module, Person, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 8, ...>>, %Person{name: nil, age: nil}}

You can define a structure combining both fields with explicit default values, and implicit nil values. In this case you must first specify the fields which implicitly default to nil:

defmodule UserC do

defstruct [:email, name: "John", age: 27]

end{:module, UserC, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 8, ...>>, %UserC{email: nil, name: "John", age: 27}}

%UserC{}

%UserC{age: 27, email: nil, name: "John"}%UserC{email: nil, name: "John", age: 27}

Doing it in reverse order will raise a syntax error:

defmodule UserD do

defstruct [name: "John", age: 27, :email]

endYou can also enforce that certain keys have to be specified when creating the struct via the @enforce_keys module attribute:

defmodule Car do

@enforce_keys [:make]

defstruct [:model, :make]

end{:module, Car, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 10, ...>>, %Car{model: nil, make: nil}}

%Car{}Enforcing keys provides a simple compile-time guarantee to aid developers when building structs. It is not enforced on updates and it does not provide any sort of value-validation

%{name: "Miguel"} = %User_B{}%User_B{name: "Miguel", age: 35}

%{name: "Migul"} = %User_B{}listC = [1, 2, 3, :a, "name"][1, 2, 3, :a, "name"]

[^head | resto] = listC[1, 2, 3, :a, "name"]

[2 | resto] = listCA quick reminder on pin operator

student = ["john", 30]["john", 30]

[name, age] = student["john", 30]

name"john"

age30

[^name, age] = ["grace", 30]Pattern matching on Enum

- Assignment

- use pipe operator to get the count of a list using Enumerable protocol on map/list/tuple

listD = [2, 4, 5, 6][2, 4, 5, 6]

listD |> Enumerable.count(){:ok, 4}

A binary is a chunk of bytes

You can create binaries by enclosing the byte sequence between << and >> operators.

<<1, 2, 3>>Each number represents the value of the corresponding byte. If you provide a byte value bigger than 255, it’s truncated to the byte size:

# 1

<<257>>

# 0

<<256>>You can specify the size of each value and thus tell the compiler how many bits to use for that particular value:

<<257::16>><<257::32>>If the total size of all the values isn’t a multiple of 8, the binary is called a bitstring — a sequence of bits:

<<257::12>>You can also concatenate two binaries or bitstrings with the operator <>:

<<2>> <> <<4>>"This is a string"The most common way to use strings is to specify them with the familiar double-quotes

result is printed as a string, but underneath it’s a binary — nothing more than a consecutive sequence of bytes.

Elixir provides support for embedded string expressions. You can use #{} to place an Elixir expression in a string constant. The expression is immediately evaluated, and its string representation is placed at the corresponding location in the string:

"Embedded expression: #{3 + 0.14}"And strings don’t have to finish on the same line:

# "\r \n \" \\"

"

This is

a multiline string

"another syntax for declaring strings

In this approach, you enclose the string inside ~s():

~s(This is also a string)Sigils can be useful if you want to include quotes in a string:

~s("Do... or do not. There is no try." -Master Yoda)There’s also an uppercase version ~S that doesn’t handle interpolation or escape characters ():

~S(Not interpolated #{3 + 0.14})~S(Not escaped \n)Finally, there’s a special heredocs syntax, which supports better formatting for multiline strings. Heredocs strings start with a triple double-quote. The ending triple double-quote must be on its own line:

"""

Heredoc must end on its own line \"""

"""Because strings are binaries, you can concatenate them with the <> operator:

"String" <> " " <> "concatenation"The alternative way of representing strings is to use single-quote syntax:

~c"abc"[64, 66, 67]~c"Interpolation: #{3 + 0.14}"~c(Character list sigil)~C(Unescaped sigil #{3 + 0.14})~c"""

hey mike

"""even the runtime doesn’t distinguish between a list of integers and a character list. When a list consists of integers that represent printable characters, it’s printed to the screen in the string form. Just like with binary strings, there are syntax counterparts for various definitions of character lists

Character lists aren’t compatible with binary strings. Most of the operations from the String module won’t work with character lists. In general, you should prefer binary strings over character lists.

In Elixir, a function is a first-class citizen, which means it can be assigned to a variable.

Assigning a function to a variable doesn’t mean calling the function and storing its result to a variable. Instead, the function definition itself is assigned, and you can use the variable to call the function.

To create a function variable, you can use the fn construct:

square = fn x ->

x * x

endThe variable square now contains a function that computes the square of a number. Because the function isn’t bound to a global name, it’s also called an anonymous function or a lambda.

You can call this function by specifying the variable name followed by a dot (.) and the arguments:

square.(8)You may wonder why the dot operator is needed here. The motivation behind the dot operator is to make the code more explicit. When you encounter a square.(5) expression in the source code, you know an anonymous function is being invoked. In contrast, the expression square(5) is invoking a named function defined somewhere else in the module. Without the dot operator, you’d have to parse the surrounding code to understand whether you’re calling a named or an anonymous function.

The & operator, also known as the capture operator, takes the full function qualifier — a module name, a function name, and an arity — and turns that function into a lambda that can be assigned to a variable. You can use the capture operator to simplify the call

Enum.each([1, 2, 3, 4], &IO.puts/1)The capture operator can also be used to shorten the lambda definition, making it possible to omit explicit argument naming. For example, you can turn this definition

lambda = fn x, y, z -> x * y + z end

lambda.(1, 2, 3)lambda = &(&1 * &2 + &3)

lambda.(5, 6, 10)

# The return value 40 amounts to 5 * 6 + 10 , as specified in the lambda definition.This snippet creates a three-arity lambda. Each argument is referred to via the &n placeholder, which identifies the nth argument of the function. You can call this lambda like any other:

A lambda can reference any variable from the outside scope:

outside_var = 5

my_lambda = fn ->

# Lambda references a variable from the outside scope

IO.puts(outside_var)

end

my_lambda.()As long as you hold the reference to my_lambda, the variable outside_var is also accessible. This is also known as closure : by holding a reference to a lambda, you indirectly hold a reference to all variables it uses, even if those variables are from the external scope.

closure always captures a specific memory location. Rebinding a variable doesn’t affect the previously defined lambda that references the same symbolic name

outside_var = 5

# Lambda captures the current location of outside_var

lambda = fn -> IO.puts(outside_var) end

# Rebinding doesn’t affect the closure.

outside_var = 6

# Proof that the closure isn’t affected

lambda.()A range is an abstraction that allows you to represent a range of numbers. Elixir even provides a special syntax for defining ranges:

lltt = 1..5

# You can ask whether a number falls in the range by using the in operator:

6 in llttRanges are enumerable, so functions from the Enum module know how to work with them. Earlier you met Enum.each/2, which iterates through an enumerable. The following example uses this function with a range to print the first three natural numbers:

Enum.each(

1..3,

&IO.puts/1

)It’s important to realize that a range isn’t a special type. Internally, it’s represented as a map that contains range boundaries. You shouldn’t rely on this knowledge, because the range representation is an implementation detail, but it’s good to be aware that the memory footprint of a range is very small, regardless of the size. A million-number range is still just a small map.

A keyword list is a special case of a list, where each element is a two-element tuple, and the first element of each tuple is an atom. The second element can be of any type.

days = [{:monday, 1}, {:tuesday, 2}, {:wednesday, 3}]

# Elixir allows a slightly more elegant syntax for defining a keyword list:

days = [monday: 1, tuesday: 2, wednesday: 3]

# Both constructs yield the same resultKeyword.get(days, :monday)

# Keyword.get(days, :noday) -> nilJust as with maps, you can use the operator [] to fetch a value:

days[:tuesday]Don’t let that fool you, though. Because you’re dealing with a list, the complexity of a lookup operation is O(n).

IO.inspect([100, 200], width: 4)days = MapSet.new([:monday, :tuesday, :wednesday])

# MapSet.member?(days, :monday) -> true

# MapSet.member?(days, :noday) -> false

days = MapSet.put(days, :thursday)

# A MapSet is also an enumerable, so you can pass it to functions from the Enum module

Enum.each(days, &IO.puts/1)- Elixir code is divided into modules and functions.

- Elixir is a dynamic language. The type of a variable is determined by the value it holds.

- Data is immutable — it can’t be modified. A function can return the modified version of the input that resides in another memory location. The modified version shares as much memory as possible with the original data.

- The most important primitive data types are numbers, atoms, and binaries.

- There is no Boolean type. Instead, the atoms true and false are used.

- There is no nullability. The atom nil can be used for this purpose.

- There is no string type. Instead, you can use either binaries (recommended) or lists (when needed).

- The built-in complex types are tuples, lists, and maps. Tuples are used to group a small, fixed-size number of fields. Lists are used to manage variable-size collections. A map is a key/value data structure.

- Range, keyword lists, MapSet, Date, Time, NaiveDateTime, and DateTime are abstractions built on top of the existing built-in types.

- Functions are first-class citizens.

- Module names are atoms (or aliases) that correspond to .beam files on the disk.

- There are multiple ways of starting programs: iex, elixir, and the mix tool.

pattern matching in functions

defmodule Function_pattern do

# will be of arity 1

def sum({a, b}) do

# def sum(a,b) do #will be of arity 2

a + b

end

end

# Function_pattern.sum 4,5

Function_pattern.sum({4, 5})9

defmodule User_details do

# uses multiclause functions

# first user clause

def user(:admin, name, phone) do

IO.puts(name)

IO.puts(phone)

end

# second user clause

def user(:normaluser, name) do

IO.puts(name)

end

end{:module, User_details, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 7, ...>>, {:user, 2}}

can take &1 , &2 meaning argument 1 argument 2 and so on

on compilation it is assign

fn x -> x end#Function<42.105768164/1 in :erl_eval.expr/6>

can also be represented as

& &1#Function<42.105768164/1 in :erl_eval.expr/6>

provide a consice way of short line functions

# mult of a number

&(&1 * &2 / &3 + &4)#Function<39.105768164/4 in :erl_eval.expr/6>

If, for instance, you call my_admin.(a, b, c, d), where a, b, c, and d are arguments, it will result in an error because my_admin is specifically defined to have arity 3. Similarly, calling my_user.(x, y, z) would result in an error for the same reason.

# using the famous gigo ... garbage in gargabe out

# we can assign our functions to a lambda fn using the capture operator

# how?

# will be of arity 3

my_admin = &User_details.user(&1, &2, &3)

# &User_details.user/3

# will be of arity 2

my_user = &User_details.user(&1, &2)

# &User_details.user/2&User_details.user/2

This is where the concept of GIGO comes into play. If you provide arguments that do not match the expected arity, or if the patterns defined in your functions don't align with the structure of the input data, you may get unexpected results or errors.

Garbage In, Garbage Out" (GIGO) essentially conveys the idea that if you provide a system with incorrect or nonsensical input (garbage), you shouldn't expect meaningful or correct output. This concept is widely applicable across various domains, emphasizing the importance of input quality in achieving desirable results.

my_admin.(:admin, "mikeAdmin", 07_394_837_336)

# mikeAdmin

# 7394837336

# so waht if we give my_admin an aruty of 2

my_admin.(:admin, "mikeAdmin")

# &User_details.user/3 with arity 3 called with 2 arguments (:admin, "mikeAdmin")mikeAdmin

7394837336

my_user.(:normaluser, "mongo")

# same if you give it an arity of 3

my_user.(:normaluser, "mongo", 89898)mongo

This explains the Garbage in Garbage out also applies to pattern matching since you are trying to match to a pattern you gave it

pattern matching plays a crucial role, GIGO can be related to the patterns you use in function heads. When you define functions with multiple clauses and patterns, the system will match the input against those patterns, and the result will depend on how well the input matches the expected patterns.

In functional programming, the clarity of your pattern matching and the adherence of your input data to those patterns are crucial for reliable and predictable program behavior. It emphasizes the importance of validating and ensuring the correctness of your input data before processing it through your functions to avoid unintended consequences.

To excape runtime errors one can write a function to handle uncertainity

defmodule Multi_clause do

def area(:circle, radius) do

# Calculate the area of a circle using the formula: π * r^2

Kernel.ceil(:math.pi() * :math.pow(radius, 2))

end

def area(_shape, _arg1) do

{:error, "Invalid arguments for the area of a circle"}

end

def area(:rectangle, length, width) do

length * width

end

def area(_shape, _arg1, _arg2) do

{:error, "Invalid arguments for the area of a rectangle"}

end

def area(_shape, _arg1, _arg2, _rr) do

{:error, "Invalid arguments...."}

end

end{:module, Multi_clause, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 9, ...>>, {:area, 4}}

Multi_clause.area(:circle, 5)79

The guard is a logical expression that places further conditions on a clause. The set of operators and functions that can be called from guards is very limited. In particular, you may not call your own functions, and most of the other functions won’t work. These are some examples of operators and functions allowed in guards:

- Comparison operators (==, !=, ===, !==, >, <, <=, >=)

- Boolean operators (and, or) and negation operators (not, !)

- Arithmetic operators (+, -, *, /)

- Type-check functions from the Kernel module (for example, isnumber/1, is atom/1, and so on)

defmodule GuardsFunctions do

defguard check_age(age) when is_number(age) and age >= 18

defguard check_age_less(age) when is_number(age) and age < 18

end

defmodule Guard_Implementation do

import GuardsFunctions

# def get_age(age) when is_number(age) and age >= 18 do

# IO.puts("You are an adult")

# end

# def get_age(age) when is_number(age) and age < 18 do

# IO.puts("You cannot drink")

# end

def get_age(age) when check_age(age) do

IO.puts("You are an adult")

end

def get_age(age) when check_age_less(age) do

IO.puts("You cannot drink")

end

def get_age(_agee) do

{:error, "Invalid age details..."}

end

end{:module, Guard_Implementation, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 7, ...>>, {:get_age, 1}}

In some cases, a function used in a guard may cause an error to be raised. For example, length/1 makes sense only on lists. Imagine you have the following function that calculates the smallest element of a non-empty list:

defmodule ListHelper do

def smallest(list) when length(list) > 0 do

Enum.min(list)

end

def smallest(_), do: {:error, :invalid_argument}

end{:module, ListHelper, <<70, 79, 82, 49, 0, 0, 7, ...>>, {:smallest, 1}}

You may think that calling ListHelper.smallest/1 with anything other than a list will raise an error, but this won’t happen. If an error is raised from inside the guard, it won’t be propagated, and the guard expression will return false. The corresponding clause won’t match, but some other might. In the preceding example, if you call ListHelper.smallest(123), you’ll get the result

{:error, :invalid_argument}This demonstrates that an error in the guard expression is internally handled.

- Anonymous functions (lambdas) may also consist of multiple clauses.

- recall the basic way of defining and using lambdas:

# Defines a lambda

double = fn x -> x * 2 end#Function<42.105768164/1 in :erl_eval.expr/6>

# Calls a lambda

double.(3)6

lambda syntax has the following shape

fn

pattern_1, pattern_2 ->

#... Executed if pattern_1 matches,

pattern_3, pattern_4 ->

#...Executed if pattern_2 matches

...

endreimplementing the test/1 function that inspects whether a number is positive, negative, or zero

test_num =

fn

x when is_number(x) and x < 0 ->

:negative

0 ->

:zero

x when is_number(x) and x > 0 ->

:positive

end#Function<42.105768164/1 in :erl_eval.expr/6>

Notice: There’s no special ending terminator for a lambda clause. The clause ends when the new clause is started (in the form pattern →) or when the lambda definition is finished with end.

Because all clauses of a lambda are listed under the same fn expression, the parentheses for each clause are by convention omitted. In contrast, each clause of a named function is specified in a separate def (or defp) expression. As a result, parentheses around named function arguments are recommended

test_num.(-1):negative

test_num.(0):zero

test_num.(1):positive

- The if statement executes the command if the specified condition is truth, and unless does the opposite, the command is executed if the condition is false.

#example of if condition

color="blue"

if color == "blue" do

"yes"

end

# output: "yes"#example of a one liner

if color == "blue", do: "yes

#example 2 of unless which does the opposite

color="blue"

unless color == "blue" do

"yes"

end

# output: nil

unless color != "blue" do

"yes"

end

# output: "yes"#example of a one liner

unless color == "blue", do: "yes

nil

#example of if else condition

color="blue"

if color == "red" do

"yes"

else

"no"

end

# output: "no"

#example of a one liner

if color == "blue", do: "yes, else: "no"

# output: "no"same can happen to unlesss (else)

syntax

case expression do

pattern_1 -> #pattern here indicates that it deals with pattern matching.

...

pattern_2 ->

...

...

end- In the case construct, the provided expression is evaluated, and then the result is matched against the given clauses.

- The first one that matches is executed, and the result of the corresponding block (its last expression) is the result of the entire case expression.

- If no clause matches, an error is raised.

Note: The case construct is most suitable if you don’t want to define a separate multiclause function.

In fact, the general case syntax can be directly translated into the multiclause approach:

defp fun(pattern_1), do: ...

defp fun(pattern_2), do: ...

... #The default clause that always matches- The with special form, an be very useful when you need to chain a couple of expressions and return the error of the first expression that fails.

- Take a scenario:

Suppose you need to process registration data submitted by a user. The input is a map, with keys being strings (“login”, “email”, and “password”).

%{

"login" => "alice",

"email" => "alice@gmail.com",

"password" => "password",

"other_field" => "some_value",

"yet_another_field" => "...",

...

}Task is to normalize this map into a map that contains only the fields login, email, and password.

if the set of fields is well-defined and known upfront, you can represent the keys as atoms. Therefore, for the given input, you can return the following structure:

%{login: "alice", email: "some_email", password: "password"}syntax

with pattern_1 <- expression_1,

pattern_2 <- expression_2,

...

do

...

endYou start from the top, evaluating the first expression and matching the result against the corresponding pattern. If the match succeeds, you move to the next expression. If all the expressions are successfully matched, you end up in the do block, and the result of the with expression is the result of the last expression in the do block. If any match fails, however, with will not proceed to evaluate subsequent expressions. Instead, it will immediately return the result that couldn’t be matched.

Example

iex(1)> with {:ok, login} <- {:ok, "alice"},

{:ok, email} <- {:ok, "some_email"} do

%{login: login, email: email}

end

%{email: "some_email", login: "alice"}also can be written as

{:ok, login} = {:ok, "alice"}

{:ok, email} = {:ok, "email"}

%{login: login, email: email}NB: The benefit of with is that it returns the first term that fails to be matched against the corresponding pattern:

iex(2)> with {:ok, login} <- {:error, "login missing"},

{:ok, email} <- {:ok, "email"} do

%{login: login, email: email}

end

{:error, "login missing"}defp extract_login(%{"login" => login}), do: {:ok, login}

defp extract_login(_), do: {:error, "login missing"}

defp extract_email(%{"email" => email}), do: {:ok, email}

defp extract_email(_), do: {:error, "email missing"}

defp extract_password(%{"password" => password}), do: {:ok, password}

defp extract_password(_), do: {:error, "password missing"}

def extract_user(user) do

with {:ok, login} <- extract_login(user),

{:ok, email} <- extract_email(user),

{:ok, password} <- extract_password(user) do

{:ok, %{login: login, email: email, password: password}}

end

end- This code is much shorter and clearer. You extract desired pieces of data, moving forward only if you succeed.

- If something fails, you return the first error. Otherwise, you return the normalized structure.

$ iex user_extraction.ex

iex(1)> UserExtraction.extract_user(%{})

{:error, "login missing"}

iex(2)> UserExtraction.extract_user(%{"login" => "some_login"})

{:error, "email missing"}

iex(3)> UserExtraction.extract_user(%{"login" => "some_login",

"email" => "some_email"})

{:error, "password missing"}

iex(4)> UserExtraction.extract_user(%{"login" => "some_login",

"email" => "some_email",

"password" => "some_password"})

{:ok, %{email: "some_email", login: "some_login", password: "some_password"}}