This repository contains the code for Text2Building, an attempt by myself to adapt the code for the paper "CLIP-Forge: Towards Zero Shot Text-to-Shape Generation" to the domain of 3D building models.

The goal of this project is to explore using cutting-edge breakthroughs in generative artficial intellience to democratize the building design process.

Buildings and cities have become dramatically more complex over the last 150 years. The 2022 revision of the New York City construction codes, which just came into effect, has 88 chapters and 34 appendices. 15 chapters alone refer to plumbing codes. Mandates for increased sustainability add further complexity. The creation of buildings has never been more expensive, and yet cities need new construction to become more sustainable and equitable. In the United States as a whole, the Federal Housing Finance Agency house price index shows that an average home costs 5.5 times what it did in 1980. This is causing a true affordability crisis.

In tandem with physical complexity, the socio-political problems around construction within our urban centers have also risen: Some communities have grown increasingly distrustful of the development process due to a long history of misguided or malevolent urban development practices. Other communities have economic incentives that are unaligned with the greater good, and want constricted housing supply so as to increase their own home prices. Often these groups are wealthy and wield disproportionate political power. This persists despite a growing body of research showing that the lack of affordable housing drives many other social maladies, like rising levels of obesity, falling fertility rates, low productivity growth, and rising wealth inequality.

Satisfactory answers to this crisis are elusive. Do we demolish historic neighborhoods to replace them with highrises? Do we sacrifice on sustainable building practices to make homes cheaper? Do we relax building codes, perhaps reducing the resiliency and even safety of our new buildings? The answers are impossible to arrive at axiomatically, and will depend on each community and situation. This set of indeterminate contrasting forces obstructing any clear solution to our predicament is known as a Wicked Problem. In the face of Wicked Problems, an effective solution is iterative design incorporating extensive feedback from all affected parties. Stakeholders present their ideal visions to one another and see where the gaps between their visions lie, and then create a new shared vision that attempts to find a middle ground between their competing ideals. This process does not succeed after the first attempt, and needs to be repeated until sufficient trust is established and until enough dimensions of the contrasting visions have been hashed out and resolved. This process is slow, expensive, and time-consuming, but necessary and important.

Slow, expensive processes are often the first to be cut under time and budgetary constraints. A clear way that tech can help is by making the process of designing buildings faster and cheaper. Architects typically charge around 10% of the construction cost for a project, and closer to 12% in NYC. Turnaround times can be days, weeks, or months, depending on the complexity of the project. Reducing these costs would allow for cheaper, faster iteration and thus more iteration. The more attempts stakeholders can have to come to a shared vision, the more satisfactory the end result is likely to be for all parties.

The hope is that generative algorithms, especially generative AI, can be leveraged to dramatically reduce these design costs and speed up iteration cycles. My hope is that these techniques will also help to democratize the design conversation: If going back to the drawing board after receiving critical feedback during a community meeting costs only a modicum of time and money, it may become more possible to deeply consider the needs of all people when building while still reducing costs.

The field of 3D generative AI is evolving extremely rapidly. Extensive work is being done to enable the creation of 3D geometry with a variety of different input modalities, such as 2D images, incomplete 3D geometry, point clouds, videos, and text.

I explored recent advancements and challenges in text-to-shape generation, focusing on zero-shot learning and multimodal approaches. The main paper used in this review is "CLIP-Forge: Towards Zero-Shot Text-to-Shape Generation," which proposes a simple yet effective method for zero-shot text-to-shape generation using an unlabelled shape dataset and a pre-trained image-text network such as CLIP. This work demonstrates promising zero-shot generalization and provides extensive comparative evaluations.

Another significant paper is "AutoSDF: Shape Priors for 3D Completion, Reconstruction, and Generation," which proposes an autoregressive prior for 3D shapes to solve multimodal 3D tasks such as shape completion, reconstruction, and generation. The paper presents a non-sequential autoregressive distribution over a discretized, low-dimensional, symbolic grid-like latent representation of 3D shapes, which allows for the representation of distributions over 3D shapes conditioned on information from an arbitrary set of spatially anchored query locations. Although the approach is more complex, it shows potential in outperforming specialized state-of-the-art methods trained for individual tasks.

"SDFusion: Multimodal 3D Shape Completion, Reconstruction, and Generation" presents a novel framework built to simplify 3D asset generation for amateur users by supporting a variety of input modalities, including images, text, and partially observed shapes. The approach is based on an encoder-decoder, compressing 3D shapes into a compact latent representation upon which a diffusion model is learned. The model supports various tasks, outperforming prior works in shape completion, image-based 3D reconstruction, and text-to-3D, making it a promising swiss-army-knife tool for shape generation.

Lastly, "Graph Neural Networks in Building Life-Cycle: A Review" examines the application of graph neural networks (GNNs) in the building lifecycle. The paper identifies ten application domains from the planning stage to the operation stage and discusses the challenges and opportunities of GNNs adoption in architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC). Although the adoption of GNNs is still in its infancy, the paper highlights the potential for future research.

Additional papers worth considering include "Vitruvio: 3D Building Meshes via Single-Perspective Sketches," "Zero-Shot Text-Guided Object Generation with Dream Fields," and "GAUDI: A Neural Architect for Immersive 3D Scene Generation." These papers further explore text-to-shape generation, zero-shot learning, and multimodal approaches in the context of 3D building meshes, object generation, and immersive 3D scene generation, respectively.

I considered several different possible datasets when starting this project. My first thought was to use one or more of the existing 3D building model datasets that exist for real-life cities. Such datasets exist for a number of cities, such as New York City, Boston, Montreal, and Berlin. These datasets are compelling because of their vastness. For example, the NYC datatset for Manhattan alone contains 45,848 3D building models. They are also compelling because, being derived from real buildings, there is no risk of a domain gap between our training data and my goal, which is to generate realistic building models from text.

Ultimately, these datasets proved unsatisfactory, however. These building models mostly contain 3D models in "LOD 1", meaning that only slightly more detail than a bounding box for the building is captured. Some of these datasets capture more roof details, but very few capture geometric facade details. These datasets are generally intended for low-detail visualization or macro-scale simulation and analysis, and are not well-suited to architectural visualization.

Another dataset, BuildingNet, ended up being better aligned to this task. This dataset contains 2,000 human-created, detailed 3D models of buildings. These models are largely of the style and form that one would expect for architectural visualization—most seem to have been made in SketchUp or similar tools.

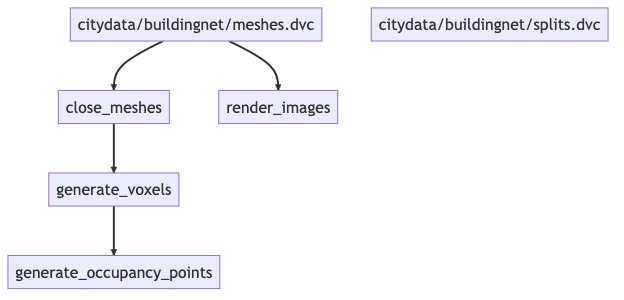

These 2,000 3D models require extensive normalization and are derived into a series of other artifacts. The code for this is in the sibling repo for this project. That repo contains instructions for running and obtaining the data used in this project.

Normalization steps include:

- Turning each mesh into a watertight mesh using ManifoldPlus.

- Removing isolated dangling components from each mesh. This is a heuristic to remove components from the meshes that may not correspond to the main building mass, such as trees, people, cars, etc.

- Removing the ground plane from each mesh. A number of meshes include some sort of floor surface which in some cases is significantly larger than the building mesh itself.

Artifact generation steps included:

- Rendering textured, shaded images of each building mesh from 12 different evenly spaced angles rotated around the Z-axis.

- Generating 32x32x32 BINVOX voxel representations of each building mesh using

cuda_voxelizer. - Generating 100,000-element occupancy point clouds by sampling points at randomly within the bounding box of the voxel volume and checking if they were contained by the voxel volume itself.

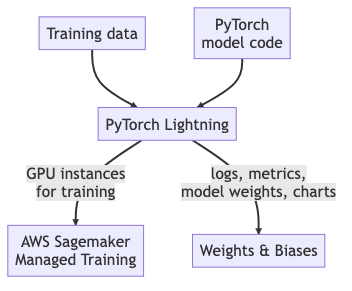

Significant effort was spent on adapting the code inherited from the Clip-Forge project to use current training infrastructure best practices. The main efforts in this space were the following:

- Adopting PyTorch Lightning to manage training code. PyTorch Lightning is a Python library designed to dramatically reduce the amount of boilerplate code required for most model training. It contains built-in functionality for implementing training and inference loops and for managing loading training data in batches and in different splits. It builds upon this basic boilerplate to enable easy generation of CLIs from model parameters, single-switch activation of model debugging and training techniques like single-batch overfitting and mixed-precision training, among many other features. I chose to adopt PyTorch as a way to distill away the non-original parts of the codebase and focus purely on the model architecture.

- Enabling the usage of AWS SageMaker Managed Training. In particular, some effort was spent to enable the usage of Spot Training, which allows for up to 40% cost savings if your training is adapted to be interruptable and resumable. Managed training allows for horizontally scalable training, which allowed me to run many experiments concurrently, and to choose the best instances for the job so as to minimize spent time waiting for training to complete. It also made training a largely push-button process, reducing time spent managing instances, babying computers, and worrying about crashed or failed training runs.

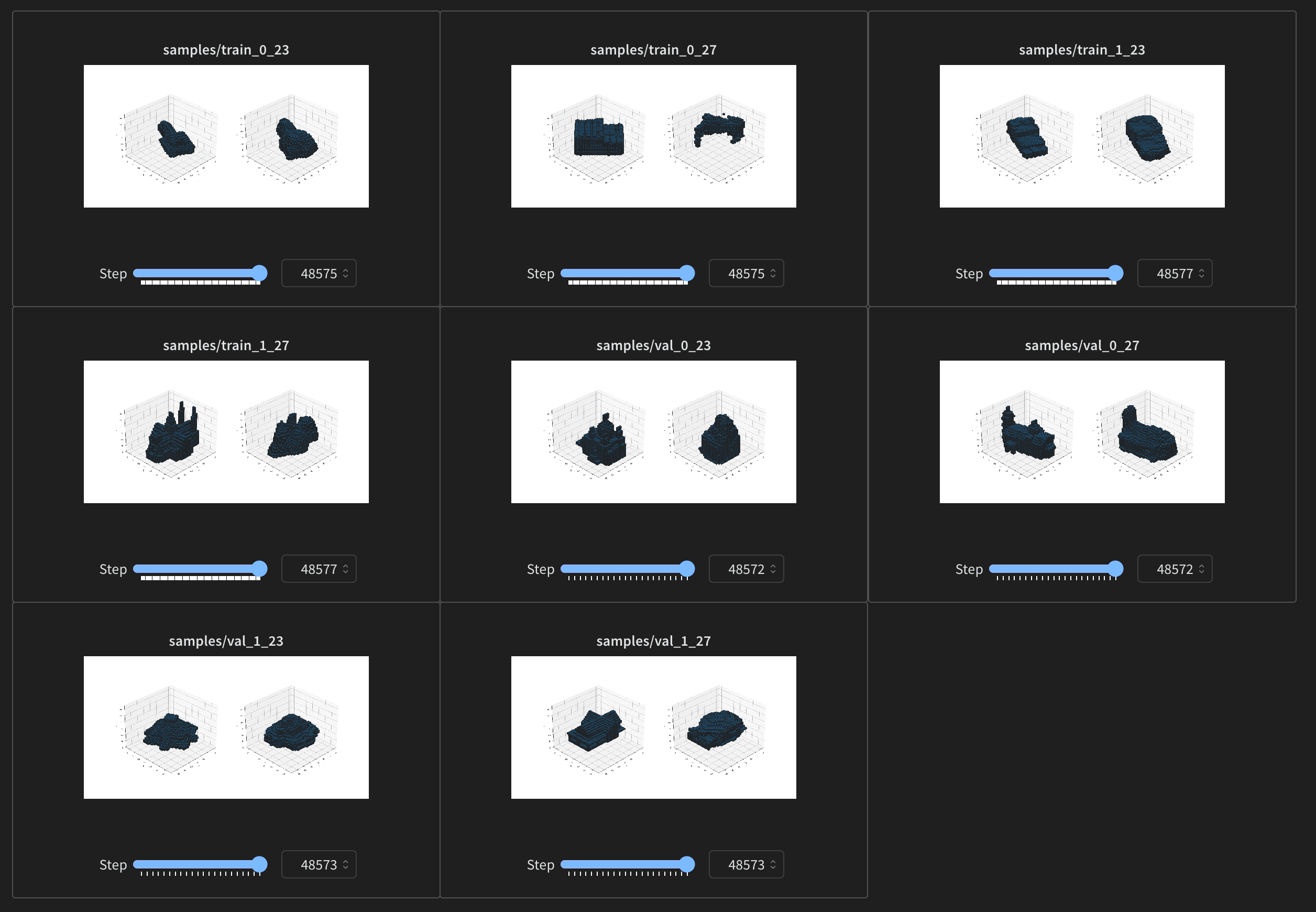

- Adopting Weights & Biases for experiment management. W&B is a cloud platform for tracking all information about ML experiments. By outputting all of my metrics and model artifacts to a single location, I was able to effectively track model performance in many dimensions across many experiments and to be confident that I could always roll back and refer to model weights that would correspond to my best performing models. I would also know what git commit and hyperparameters produced that model.

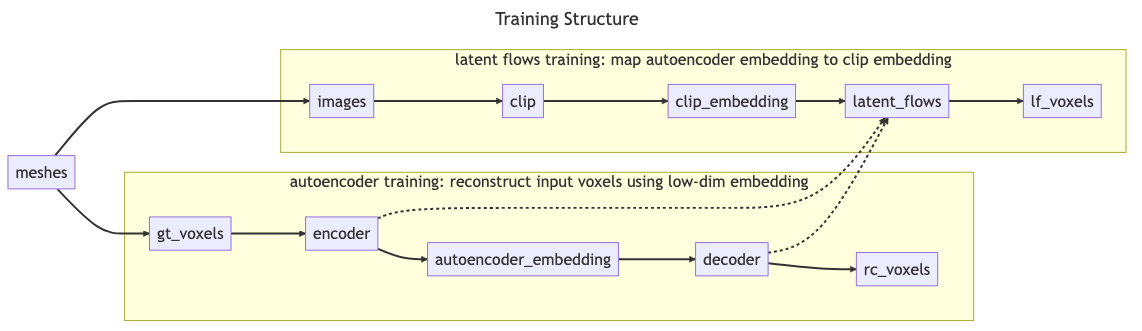

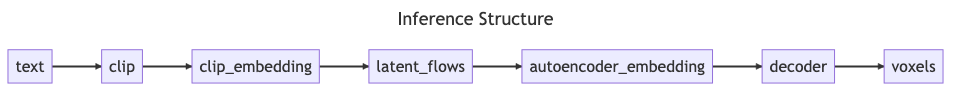

The model architecture largely mirrors the structure of the CLIP-Forge paper. Training occurs in two phases: In the first phase, I train an autoencoder to learn a lower-dimensional representation of 32x32x32 voxel representations of the 3D building meshes. In the second phase, I generate 2D image renderings of the 3D building meshes from a variety of angles and compute CLIP embeddings using those images. I then train a Latent Flows network to map the distribution of the learned autoencoder embeddings to the distribution of the CLIP embeddings.

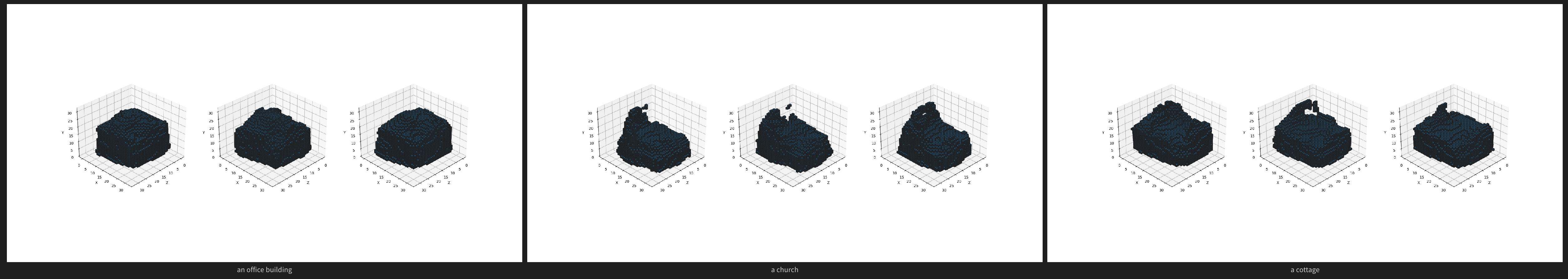

During inference, the input is a text phrase. This text phrase is encoded into an embedding by CLIP, which can then be brought into the embedding space of the autoencoder using the Latent Flows network. We then decode the embedding to arrive at a voxel representation of the text phrase.

The autoencoder differs somewhat from the CLIP-Forge autoencoder in that it is a variational autoencoder (VAE), whose learned features attempt to model a high-dimensional gaussian representation of the principal features of the training data, as opposed to trying to encode the features directly. This type of autoencoder proved to be more robust in my testing, likely due to a VAE's ability to generate plausible results when randomly sampled. The final autoencoder consists of 5 layers of batch-normalized 3D convolutional layers with rectified linear unit activiation and a final fully-connected layer.

The Latent Flows network remains identical to that used in the CLIP-Forge paper. This network consists of a sequence of 5 batch-normalized "coupling layers", which in turn each contain scale and translate networks. The scale networks consist of 3 fully connected layers interspersed with tanh activation, and the translation networks consist of 3 fully connected layers interspersed with rectified linear unit activation.

CLIP is a model provided by OpenAI and is considered frozen for the purposes of this experiment. Its use, as can be inferred from the above, is to join the text and 2D image modalities into a single shared embedding space. I am interested in trying out other competing models for generating joint text-image embeddings in the future.

The steps taken for training and inference are detailed above. Also pictured above are sample results from the autoencoder and sample results from sampling the end-to-end network using text.

A more detailed treatment of Autoencoder performance results can be found in the living document here. Suffice to say, end-to-end is currently inadequate for this approach to be useful for architectural visualization. While the autoencoder demonstrates some ability to expresss signficant architectural features of the buildings, when attempting to sample into the embedding space using text, outputs are largely noise.

Further work is needed to diagnose the issue here. Most effort was spent on improving the autoencoder performance, while relatively little effort was spent on diagnosing the performance of the CLIP embeddings or of the Latent Flows network.

A key limitation is data. With a larger, cleaner dataset of 3D building models, we can use more powerful models and still generalize.

LOD-2 3D models of every building in NYC and Zurich, made easily usable. In particular, the Zurich buildings seem interesting.

Cities: Skylines is a citybuilding videogame in the lineage of SimCity. It has been out for over 8 years and has a vibrant modding community, which has produced thousands of 3D models of buildings for use in the game.

These 3D models are relatively consistent in quality and visual style. They have a relatively high level of detail, a relatively low polygon count, and relatively good model topologies, all being intended for use in the same videogame.

These 3D models are not particularly easy to access. Steam, the primary distributor for the game and its mods, does not allow users to batch download mods. A (questionably legal) mirror of many of these mods exists at smods.ru, which allows direct download. We could scrape this website and download the building mods. This would give us CRP files, which would typically contain a Unity Mesh in there.

We could then use a tool like http://unera.se/crper/,

which is able to parse CRP files. Inspect its source code and view crper.js.

More info is available here:

https://cslmodding.info/dump/

Info about exporting unity meshes to FBX/OBJ: https://www.noveltech.dev/export-mesh-unity/

Recently released by the Allen Institute for AI, the Objaverse dataset consists of over 800,000 annotated 3D models sourced from throughout the Internet. Preliminiary investigation shows that this dataset includes at least 1,000 models of buildings that are easily discoverable. The potential of this dataset is significant, as it could easily double or more the usable data for this experiment. They key issue with this data is that the included data varies widely in quality, detail, style, and technique. Some building models are in a cartoon style intended for animation, others for videogames. Some models may be highly normalized and intended for usage in CAD software, others may be constructed by photogrammetry of real buildings and as such have extremely noisy meshes. Figuring out how to properly normalize these meshes will be key to using them in this project.

- Neural rendering techniques, Fantasia, AutoSDF. Fine-tuning emerged foundation models.

CLIP is a model provided by OpenAI and is considered frozen for the purposes of this experiment. Its use, as can be inferred from the above, is to join the text and 2D image modalities into a single shared embedding space. I am interested in trying out other competing models for generating joint text-image embeddings in the future.

Of particular interest are CoCa

and open_clip.

As mentioned above in the performance considerations section, a possible reason for poor end-to-end performance lies in the Latent Flows model. More effort would be needed to explore potential failure modes here.