The Power of the Ceylon Type System

The Ceylon type system is immensely powerful, and you can do loads and loads of cool stuff with it. Here, I demonstrate that it is Turing complete, meaning that you can perform arbitrary calculations with it. I repeat: You can (in theory) do any calculation in the Ceylon type system, and get the result via the compiler’s type inference (for example, the “insert inferred type” quick fix in the Ceylon Eclipse IDE). But we’ll start with small steps, and first demonstrate:

Ceylon Type System is Chomsky-3-complete

The type system / typechecker of the Ceylon programming language is Chomsky-3-complete, meaning that it can recognize regular languages.

What does that mean?

It means, for example, that it is possible to define a function t, an alias Accept, an object initial, and some other internal types, such that

Accept q = t(t(t(t(t(initial, _1), _6), _7), _3), _5);compiles, but

Accept q = t(t(t(t(t(initial, _1), _6), _7), _3), _4);doesn’t, because 16735 isn’t divisible by three, but 16734 is.

In other words, this statement compiles iff the arguments to the recursive t call chain form a number that isn’t divisible by three.

(The chain can be as long as you want, or as long as the compiler can handle without a stack overflow.)

How does this work?

To explain this, we’ll first take an excursion and look at the theory of regular languages.

Theoretical stuff

First, some simple terms:

- An alphabet is a set of characters, for example

{ a, b }for very simple examples or{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 }for natural numbers. - A word over an alphabet is a sequence of characters from that alphabet.

For example,

12345would be a word over the alphabet defined above. (Warning: This is slightly different from the normal use of the term; if your alphabet contains the space character, then “The rain in spain stays mainly in the plain” is one word.) - A language is simply a set of words over an alphabet.

You can define it directly – for example,

{ 1, 12, 123 }might me the language of my favorite numbers – but most useful languages are defined over some rule that all words in the language must fulfill, like “the language of all numbers not divisible by three” or “the language of all valid Ceylon programs”. - And, last but not least, a regular language is a language that can be recognized by a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA).

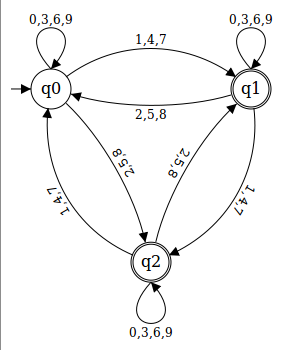

What’s a deterministic finite automaton now? It’s a theoretical concept that’s usually represented like this:

(That is a rendered version of this file, because SVGs aren’t supported in GitHub READMEs.)

Every circle represents a state that the automaton can be in; at any time, it’s in exactly one state.

We start off in the state that’s marked with a little unlabeled arrow (q0).

The automaton then reads the characters of the input word one after the other, and for each character it transitions into a different (or the same) state according to the arrow exiting the current state that’s labelled with the read character.

For example, in the automaton above, the input 16735 leads to the state transitions q0→q1→q1→q2→q2→q1.

As the last state is an accepting state – which is usually marked by a double-line border – the automaton accepts the word, which means that this word is in the language recognized by the automaton.

In this case, this is the language of all (decimal representations of) numbers that are not divisible by three:

The automaton builds the digit sum, but only remembers its remainder modulo three in the states.

Now, we want to encode that automaton into the Ceylon type system.

… transformed into code

We already saw how the result should be used:

Accept q = t(t(t(t(t(initial, _1), _6), _7), _3), _5);should compile because 16735 is accepted by the automaton that we saw earlier, which is in turn because 16735 isn’t divisible by three.

t is the state transition function. It accepts a state as first argument, an input character as second argument, and then returns the following state.

initial is the initial state, and Accept is an alias to the union of all accepting states.

Thus, the statement compiles iff the state that the function returns on the last call is assignable to the union of accepting states – that is, if it’s an accepting state.

First of all, let’s get all the boring stuff out of the way. Here’s types and objects for all states and inputs:

/* alphabet */

shared abstract class X0() of _0 {} shared object _0 extends X0() {}

shared abstract class X1() of _1 {} shared object _1 extends X1() {}

shared abstract class X2() of _2 {} shared object _2 extends X2() {}

shared abstract class X3() of _3 {} shared object _3 extends X3() {}

shared abstract class X4() of _4 {} shared object _4 extends X4() {}

shared abstract class X5() of _5 {} shared object _5 extends X5() {}

shared abstract class X6() of _6 {} shared object _6 extends X6() {}

shared abstract class X7() of _7 {} shared object _7 extends X7() {}

shared abstract class X8() of _8 {} shared object _8 extends X8() {}

shared abstract class X9() of _9 {} shared object _9 extends X9() {}

/* states */

shared interface Q of Q0|Q1|Q2 {}

"Remainder 0"

shared interface Q0 satisfies Q {}

"Remainder 1"

shared interface Q1 satisfies Q {}

"Remainder 2"

shared interface Q2 satisfies Q {}

"Accepting state(s)"

shared alias Accept => B<Q1|Q2>;

"Initial state"

shared object initial satisfies B<Q0> {}

"Input that adds no remainder"

shared alias R0 => X0|X3|X6|X9;

"Input that adds 1 to remainder"

shared alias R1 => X1|X4|X7;

"Input that adds 2 to remainder"

shared alias R2 => X2|X5|X8;That’s all not very interesting – all the magic happens in the t function.

Now, how does this function work? t can only have one return type!

Well, the basic idea is to stuff loads of information into that type by making it a union type.

We have one “branch” for each input state and input character, and then put the output state into that branch as well.

We select the correct branch by making each branch the intersection of its expected state and input, the actual state and input, and then add the resulting state to that as an intersection as well.

That gives us this:

shared

S&Q0 & C&R0 & Q0 |

S&Q0 & C&R1 & Q1 |

S&Q0 & C&R2 & Q2 |

S&Q1 & C&R0 & Q1 |

S&Q1 & C&R1 & Q2 |

S&Q1 & C&R2 & Q0 |

S&Q2 & C&R0 & Q2 |

S&Q2 & C&R1 & Q0 |

S&Q2 & C&R2 & Q1

t<S,C>(S state, C x)

given S of Q

given C of X0|X1|X2|X3|X4|X5|X6|X7|X8|X9

{ return nothing; }As you can see, all the magic happens in the return type – the function doesn’t actually do anything (which makes sense, since we’re only interested in compile-time behaviour).

Each of the three return “blocks” is for one state, and each line in there for a group of input characters (if I added a line for each individual character, it would be even bigger!).

For example, the line S&Q1 & C&R1 & Q2 evaluates to something assignable to Q2 if S is Q1 and C is of R1, and to Nothing otherwise.

Of all these branches, exactly one is not Nothing, so the total result is the union of many Nothings – which the typechecker throws away – and one interesting “branch”, which then contains the resulting state.

So does this work? Unfortunately, it doesn’t (the problem may even be obvious to you – it wasn’t to me, though). Fortunately, there’s a pretty simple fix that still keeps the same principle.

What’s the problem? Well, let’s look again at that line we had earlier: S&Q1 & C&R1 & Q2.

I said that this was assignable to Q2.

That wasn’t wrong – but the actual result isn’t really intended.

Since all the state types are disjoint (forced disjoint by the declaration of interface Q of Q0|Q1|Q2), and the type contains the intersection Q1&Q2, the resulting type is Nothing.

Of course, Nothing is assignable to everything – especially, it will propagate as S through the t chain (intersected with even more states, which changes nothing) and in the end, of course, always be assignable to Accept, no matter what we’ve entered.

To solve this, we need to somehow strip the selection part of the branch – the S&Q1 & C&R1 – from the return type, since we only care about the Q2.

For this, we introduce a new type that’s simply a “box” around another type:

"Box around a type"

shared interface B<out T> {}and use that in the function:

shared

S&Q0 & C&R0 & B<Q0> |

S&Q0 & C&R1 & B<Q1> |

S&Q0 & C&R2 & B<Q2> |

S&Q1 & C&R0 & B<Q1> |

S&Q1 & C&R1 & B<Q2> |

S&Q1 & C&R2 & B<Q0> |

S&Q2 & C&R0 & B<Q2> |

S&Q2 & C&R1 & B<Q0> |

S&Q2 & C&R2 & B<Q1>

t<S,C>(B<S> state, C x)

given S of Q

given C of X0|X1|X2|X3|X4|X5|X6|X7|X8|X9

{ return nothing; }Note that the first argument is now of type B<S> instead of S.

Even if it’s a Q0&R0&B<S>, we don’t care, since we only cherry-pick the S part.

And that’s it! Now it works, and we’ve encoded the automaton into the type system. (You can see the entire file in source/ceylon/typesystem/demo/notDivisibleByThree/automaton.ceylon.)

Ceylon Type System is Chomsky-2 complete

The next rank of the Chomsky hierarchy are context-free languages, which are all languages that can be recognized by a Pushdown Automaton. (Note: usually, context-free languages are written using a context-free grammar instead of a pushdown automaton, but both approaches are equivalent, and for our purpose, pushdown automata are much more convenient.) A pushdown automaton is basically an expansion of a finite automaton (as seen above) that in addition has a stack. With each transition, you can push or pop a character from that stack, and you can decide your target state by the current stack head in addition to the input character.

For example, this is a very simple pushdown automaton:

(That is a rendered version of this file, because SVGs aren’t supported in GitHub READMEs.)

(,ε → xmeans: if you read a(from input and nothing from the stack, pushxonto the stack.(,x → xxmeans: if you read a(from input and anxfrom the stack, pushxxonto the stack (onexto replace the one we popped, and onexthat we “actually push”).),x → εmeans: if you read a)from input and anxfrom the stack, push nothing onto the stack. (Since onexwas popped for reading, this has the effect of popping one item.)

It recognizes the language of all well-formed parentheses: Each ( pushes an item onto the stack and each ) pops it off again.

The automaton accepts the input word by empty stack: if there were as many (s as )s, and there was never a ) without a corresponding ( before it, then the parentheses are well-formed.

Let’s try turning that into a typing problem:

/* alphabet */

shared abstract class A() of a {} shared object a extends A() {}

shared abstract class B() of b {} shared object b extends B() {}

/* states */

shared interface Q of Q0 {}

shared interface Q0 satisfies Q {}

/* stack elements */

shared interface S of S0 {}

shared interface S0 satisfies S {}

"Pair of two types"

shared interface P<out T, out S> {}

shared interface Stack

of StackHead|StackEnd

{}

shared interface StackHead<out Element=S0, out Rest=Stack>

satisfies Stack

given Element satisfies S

given Rest satisfies Stack

{}

shared interface StackEnd

satisfies Stack

{}

"Accepting state(s)"

shared alias Accept => P<Q0, StackEnd>;

"Initial state"

shared object initial satisfies P<Q0, StackEnd> {}

"""State transition function for the pushdown automaton

~~

a,ε,s0

b,s0,ε

↻

~~

which accepts correct parenthetical statements ([[a]] being `(` and [[b]] being `)`) by empty stack.

"""

shared

C&A&P<Q0,StackHead<S0, Stak>> |

C&B&Stak&StackHead<S0, RestStak>&P<Q0, RestStak>

t<out Stat, out Stak, out RestStak, C>(P<Stat, Stak> state, C c)

given Stat satisfies Q

given RestStak satisfies Stack

given Stak of StackEnd|StackHead<S0, RestStak>

satisfies Stack

given C of A|B

{ return nothing; }Observe the following differences:

- Our alphabet has changed.

astands for the opening parenthesis,bfor the closing parenthesis. The stack alphabet consists of a single characterS0. - We have replaced the “box”

Bwith the “pair”P, since we need to pick both the state and the stack from the previous iteration’s return type. Acceptdoesn’t narrow the state, but instead the stack, since this automaton accepts by empty stack instead of by accepting state. (It is also acceptable I’ll show myself out for a pushdown automaton to accept by state, and this can easily be done here as well.)- And, of course, there’s now the

Stack, which is a linked list of types similar toTuple. - Last but not least,

tuses all these changes to push and pop off the stack; pushing is done by wrapping a newStackHeadaroundStak, and popping is done by droppingStakand directy returningRestStakinstead.

Looks great, let’s use it!

// The following statement is well-typed because (()()) is a well-formed parenthetical expression.

Accept end = t(t(t(t(t(t(initial, a), a), b), a), b), b);Unfortunately, that doesn’t compile – again, I first showed you an example that doesn’t work.

Why?

You get the following compile error on the second (counting right-to-left) t invocation:

Inferred type argument StackHead<S0,StackEnd> to type parameter Stak of declaration t not one of the enumerated cases of Stak

This is because the compiler infers the type Nothing for t’s RestStak type argument (which is correct behavior, not a bug, although I don’t quite understand why).

There are two possible solutions for this:

- we can explicitly specify the type arguments:

// The following statements are well-typed because (()()) is a well-formed parenthetical expression.

value s0 = initial;

value s1 = t<Q0,StackEnd,Nothing,A>(s0, a);

value s2 = t<Q0,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>,StackEnd,A>(s1, a);

value s3 = t<Q0,StackHead<S0,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>>,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>,B>(s2, b);

value s4 = t<Q0,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>,StackEnd,A>(s3, a);

value s5 = t<Q0,StackHead<S0,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>>,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>,B>(s4, b);

value s6 = t<Q0,StackHead<S0,StackEnd>,StackEnd,B>(s5, b);

Accept end = s6;But this sucks, because now the compiler isn’t doing any work for us – we’re doing all the work (stepping through the automaton), and the compiler only confirms that we’re doing it correctly. Luckily, though, there is also a solution that makes the type argument inference work:

- we can add parameters to

t

Then, the signature of t looks like this:

shared

C&A&P<Q0,StackHead<S0, Stak>> |

C&B&Stak&StackHead<S0, RestStak>&P<Q0, RestStak>

t<out Stat, out Stak, out RestStak, C>(P<Stat, Stak> state, C x, RestStak rest)

given Stat satisfies Q

given RestStak satisfies Stack

given Stak of StackEnd|StackHead<S0, RestStak>

satisfies Stack

given C of A|B

{ return nothing; }As you can see, it now has an additional parameter rest, which allows the compiler to infer the type of RestStak.

However, we also need something that we can pass to rest.

This requires the following additions to P and Stack:

"Pair of two types"

shared interface P<out T, out S> { shared formal T first; shared formal S second; }

shared interface Stack

of StackHead|StackEnd

{ shared formal Stack rest; }

shared interface StackHead<out Element=S0, out Rest=Stack>

satisfies Stack

given Element satisfies S

given Rest satisfies Stack

{ shared actual formal Rest rest; }

shared interface StackEnd

satisfies Stack

{ shared actual formal Nothing rest; }

"Initial state"

shared object initial satisfies P<Q0, StackEnd> { shared actual Q0 first = nothing; shared actual StackEnd second = nothing; }which allows us to write:

// The following statements are well-typed because (()()) is a well-formed parenthetical expression.

value s0 = initial;

value s1 = t(s0, a, s0.second.rest);

value s2 = t(s1, a, s1.second.rest);

value s3 = t(s2, b, s2.second.rest);

value s4 = t(s3, a, s3.second.rest);

value s5 = t(s4, b, s4.second.rest);

value s6 = t(s5, b, s5.second.rest);

Accept end = s6;We haven’t specified any types, but now the compiler is able to infer them and do all the work for us. Victory! (You can see the complete automaton in source/ceylon/typesystem/demo/wellFormedParentheses/automaton.ceylon and .../demo.ceylon.)

Ceylon Type System is Turing complete

Now comes the best part: the Ceylon type system is Turing complete, which means that you can perform any calculation in the type system (with one restriction, which will become clear later). Turing complete means that the Ceylon type system can emulate a Turing machine, so let’s look at these first.

A Turing machine is an abstract concept of a very simple, but still very powerful machine. Like a DFA or a pushdown automaton, it can be in one of several states which govern its behavior; however, unlike these, it does not read the input character by character, but rather operates on an indefinitely large “tape” that initially contains the input word, but to which the Turing machine can write whatever it wants and on which it can move freely. In each “step”, the Turing machine reads the character at the current position on the tape and then

- writes the same or a different character back to the tape

- moves 1 left, 1 right or stays in the same position

- transitions into the same or a different state.

The machine moves back and forth on the tape until it’s in an infinite loop: a state where it does not move and writes the same character that it just read. Then it halts. If you wanted to check some condition – if the input word is in the language that this Turing machine recognizes – then you usually check if the machine halted in an accepting state or not; if you wanted to perform some calculation, the result is left on the tape.

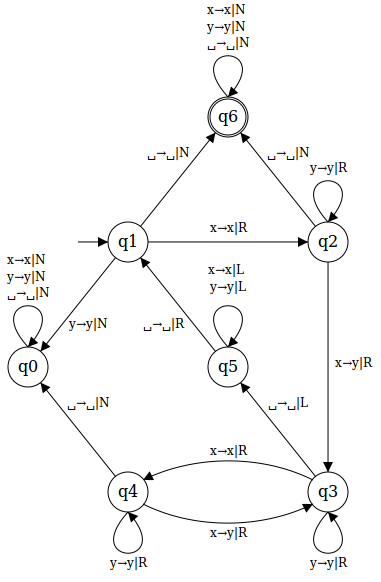

Here’s an example of a Turing machine:

(That is a rendered version of this file, because SVGs aren’t supported in GitHub READMEs.)

x→y|Rmeans: if you read anxfrom the tape, write ayto the tape and move right. (Other movements are left and no movement.)

This Turing machine accepts an input word if its length is a power of two, or in other words, it recognizes the powers of two in unary encoding.

This means that it accepts the inputs x, xx, xxxx, xxxxxxxx (length 1, 2, 4, 8), but will not accept xxx, xxxxxx (length 3, 6).

Very roughly, it works by repeatedly going over the input word, each time replacing every second x with a y, until there’s only one x left.

When it has seen an odd number of xs upon reaching the end of the word, it immediately rejects it.

A more detailed explanation follows (if I omit the written character or movement, that means that the same character is written back and the Turing machine doesn’t move):

Q0: “trash” state. It loops forever (= the Turing machine halts) without accepting.Q1: starting state, and the one we always return to when we start the next round of going over the input word. The usual transition is to read anx, move right, and go to stateQ2.Q2: state after reading exactly onex. Skips over consecutiveys until it reaches the nextx(replace withy, go toQ3) or the end of the word (there was onexleft in the word, accept it – go toQ6).Q3: state after reading an even number ofxs. Skips over consecutiveys until it reaches the nextx(go toQ4) or the end of the word (there was an even number ofxs left in the word, enter next round – go toQ5).Q4: state after reading an odd number ofxs. Skips over consecutiveys until it reaches the nextx(replace withy, go toQ3) or the end of the word (there was an odd number ofxs left in the word, abort – go toQ0).Q5: rewind state. Moves left until it reaches the beginning of the word, then goes back toQ1.

Going over the word xxxxxxxx, it is transformed into xyxyxyxy, then xyyyxyyy, and then xyyyyyyy, and then the Turing machine accepts it.

On the other hand, the word xxxxxx is transformed into xyxyxy and then the Turing machine sees an odd number of xs and rejects the word.

(With a few more states, you could record how often the Turing machine cycled over the word, and thus turn it into one that calculates the logarithm base two of a given number.)

How do you turn this into a typing problem?

It’s actually quite similar to the Chomsky-2 problem above (the matching parentheses), except that instead of one stack, you have two stacks and shift elements between them.

For example, the tape abc xyz (the space represents where the head of the Turing machine is) is represented through the two stacks abc and zyx.

If you imagine the two stacks vertically, put them next to each other, and then rotate the left one clockwise and the right one counter-clockwise, you should arrive at the horizontal tape.

Therefore, the state transition function needs two additional type paramaters for the extra stack.

On the other hand, we can lose the C (input character) because the input is now on the tape, which leaves us with the following type parameters and parameters:

t

<out State, out LeftStack, out LeftRest, out RightStack, out RightRest>

(B<State, LeftStack, RightStack> state, LeftStack leftStack, LeftRest leftRest, RightStack rightStack, RightRest rightRest)So how does the return type look without C? Let’s have a look:

// Q0 is the “trash” state that loops forever

State&Q0 & B<Q0, LeftStack, RightStack> |

// Q1 is the initial state

// test: stack starts with SX move SX from right stack to left stack

State&Q1 & RightStack&StackHead<SX, RightRest> & B<Q2, StackHead<SX, LeftStack>, RightRest> |

// test: stack starts with SY that’s not allowed, trash

State&Q1 & RightStack&StackHead<SY, RightRest> & B<Q0, LeftStack, RightStack> |

// oh, we’re done? alright, let’s accept

State&Q1 & RightStack&StackEnd & B<Q6, LeftStack, RightStack> |

// ...Alas! I have again deceived you, and shown you an example that doesn’t work. But why doesn’t it work?

Look again at how we test that the first item of the right stack is SX.

We create the intersection RightStack&StackHead<SX, RightRest>, just like we previously created the intersection C&SX.

It still clashes when the right stack doesn’t start with SX… but unfortunately, it doesn’t clash enough: the intersection is StackHead<Nothing, RightRest>, not Nothing.

This means that we end up with both Bs in the return type no matter what the input is.

To solve that problem, we have to add more type parameters and parameters to t:

t

<out State, out LeftStack, out LeftRest, out RightStack, out RightRest, Left, Right>

(B<State, LeftStack, RightStack> state, Left left, LeftRest leftRest, Right right, RightRest rightRest)

given State satisfies Q

given Left satisfies S

given Right satisfies S

given LeftRest satisfies Stack

given RightRest satisfies Stack

given LeftStack of StackEnd|StackHead<Left, LeftRest>

satisfies Stack

given RightStack of StackEnd|StackHead<Right, RightRest>

satisfies StackNow we can properly define the return type:

// this is the same, still trash

State&Q0 & B<Q0, LeftStack, RightStack> |

// Right is SX move SX from right to left stack = move to the right on tape

State&Q1 & Right&SX & B<Q2, StackHead<SX, LeftStack>, RightRest> |

// Right is SY: trash

State&Q1 & Right&SY & B<Q0, LeftStack, RightStack> |

// Right is finished done

State&Q1 & RightStack&StackEnd & B<Q6, LeftStack, RightStack> |

// ...Now, the Nothing trick works again: exactly one of the Q1 “branches” will be non-Nothing, and we’ll only see the B of that branch.

I haven’t shown you yet how this is used; for that, we need three more helper functions:

"Helper function to **b**uild an initial stack. See [[t]] for usage."

StackHead<First, Rest>

b

<out First, out Rest>

(First first, Rest rest)

given First satisfies S

given Rest of StackEnd|StackHead<S, Stack>

satisfies Stack

{ return nothing; }

StackEnd

e

()

{ return nothing; }

B<Q1, StackEnd, Input>

initial

<out Input>

(Input input)

given Input satisfies Stack

{ return nothing; }These three functions together allow us to construct the initial stack for an input word:

value s00 = initial(b(x, b(x, b(x, b(x, b(x, b(x, b(x, b(x, e())))))))));That’s eight xs pushed onto an empty stack and then turned into a tape + initial state by the initial function.

After we have that, we stick it into t repeatedly:

value s01 = t(s00, s00.second.first, s00.second.rest, s00.third.first, s00.third.rest);

value s02 = t(s01, s01.second.first, s01.second.rest, s01.third.first, s01.third.rest);

// ...The Turing machine now runs over the tape, turning the xxxxxxxx into first xyxyxyxy, then xyyyxyyy and finally xyyyyyyy, and then accepting it, all that in one iteration per function call.

This takes a while (so to speak; it’s not really time it takes), and therefore we have to write out 60 iterations until we can write:

// ...

value s60 = t(s59, s59.second.first, s59.second.rest, s59.third.first, s59.third.rest);

Accept end = s60;(where alias Accept => B<Q6, Stack, Stack>;).

And if all that compiles, then we know that 8 is indeed a power of 2. Phew!

The full example is in source/ceylon/typesystem/demo/powerOfTwo/automaton.ceylon and .../demo.ceylon.

Closing words

If you’ve read this far, congratulations! I hope you now understand how the Ceylon type system is Turing complete; if you don’t, please open an issue or send me an E-mail.

If you know any other reasonably short, but still at least sort of useful Turing machine that I could use as an example, please tell me! The “power of two” Turing machine is not an ideal “test case” for Turing completeness – for example, it never conditionally moves left. I’m pretty sure that you can indeed transform any Turing machine into a typing problem with the techniques outlined above, but I would like to try some more examples nonetheless to be absolutely certain.