Monolithic solutions or solutions where a single point of failure can derail an operation is a big problem. In products and platforms that target availability as an essential feature, this problem ends up creating major engineering challenges. This difficulty can be solved with a Microservices architecture. This architecture aims to: Make processes independent and managed in a unique way and without interdependence, so responsibilities are divided and decentralized, something very common in a distributed computing pattern. Problems happen in isolation and problems are solved.

In technology there is no perfect solution, questions about availability will always be pertinent. Is a microservices architecture fault resilient? In that case the answer is: No, totally.

Migrating between architectures will not guarantee the complete resolution of all your fault tolerance issues, in which case our issues and our solutions change name and address.

A distributed computing architecture can only be called fault tolerant if it has resilience and its patterns as the essence of its construction. We need to note that distributed components can fail, but in that case we will anticipate failures and manage them.

Conceptually, resilience assumes the premise that failures happen at any time and that we must be ready for any scenario. Questions like:

- Service A communicates with Service B only works through responses from Service C.

- What are we going to make Service B stop?

- What fallback treatment plan will we have in this circumstance?

- Work with default values?

- Request information from service C?

- Return an error message?

By applying resilience and its patterns, you will probably know how to act in the best way when idealizing and building a product, a much more favorable scenario than crises in productive environments.

When you finish a migration between monolith and Microservice, the first thing you'll notice is the number of components that need to be managed. All these interconnected components make up the solution. A good way to compare this architecture to an orchestra. Both need good tuning. In order for the orchestra to reach the audience's ecstasy, the conductor conducts the entire symphony, resilience will be the conductor of our orchestra, promoting discussions such as tolerance and dealing with failures as scenarios and not crises. For our product to perform with mastery, components cannot fail and compromise all our engineering and architecture.

Scenario Identification

Prior to our delivery to production, we perform integration, performance, unit and architectural tests. All these tests are essential for the perfect functioning of functions and code quality, but they do not mitigate failure scenarios. Mapping failure scenarios is an essential task when designing a solution. Architecture and engineering need to work closely together on the best solution for the business. The business needs to be fully together when deciding how to handle failures. Questions like:

- Are we able to map our risk and crisis scenario?

- Are we ready to support failure across the entire service layer?

- How to recover from failures quickly and with minimal impact?

The perfect scenario to address resilience within agile methodology teams is: Solutions Architects, Tech Leads and Product Owner, need an error mapping process at the time of refinement so that each feature can have its risk map and documentation containing all feature details and solution decisions. This needs to be recorded and made available for the engineering team to consult at the time of construction.

Once we have a failure mitigation plan and an automatic recovery plan, we will introduce a concept popularly known as Chaos Engineering. Where we will test and create engineering situations in which we will follow the behavior of a set of services in a crisis situation and how fault tolerance will behave in scenarios:

- Service A not communicating with other services

- Database unavailability

- Server without Communication

- High response time

- Failure in integrations in general

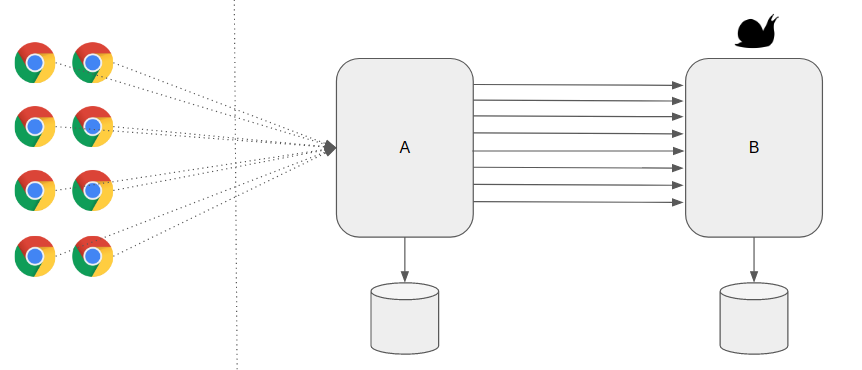

Mitigating cascading failures

Dependencies between services makes the solution prone to cascading errors, a small problem can become a big problem. So that you do not propagate errors, it is necessary to ensure that this type of failure does not occur in order to better manage network resources, using threads is a good way to network, but an essential point is that the failed service recovers from automatically.

Mitigating single points of failure

The instant we are designing something, we need to discuss fault tolerance, we need to make sure that we are designing something that is not dependent on a single component. Solutions need to be designed so that single points of failure do not exist, dealing with requests is the technology challenge and ensuring availability of the entire ecosystem is essential. In addition to mapping, recovery strategy is critical to success.

Tolerating failures is our mantra and in case of errors and exceptions we need to deal with them in the best possible way, creating messages or default values for the business, these are types of solutions that we can adopt so that failures and elegance fit in the same sentence.

Now that we have defined the concepts of fault tolerance in agile projects, recovery and resilience, we will implement the main resilience patterns. We will go in a conceptual approach with drawings that illustrate the situations, we will make available a project on GitHub that implements all the mentioned patterns so that in addition to the concept we have construction examples. The patterns that will be implemented are:

Repository with all patterns mentioned

All projects will be built with the following technologies:

- Java 17

- Spring Boot

- Lombok

- Spring Boot Actuator

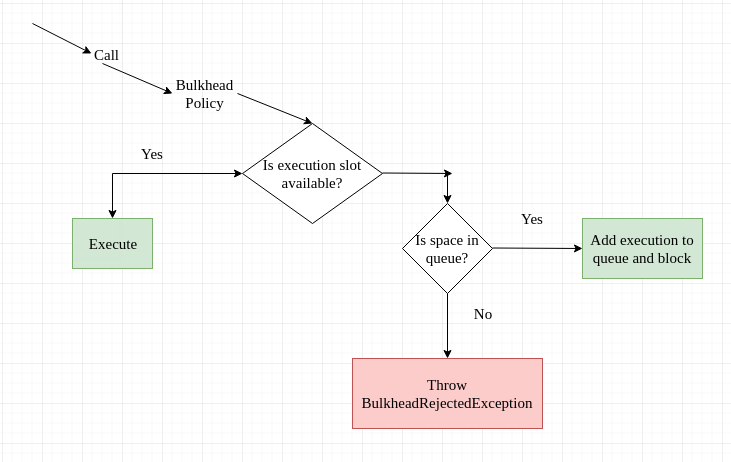

The Bulkhead pattern is a type of application design that is tolerant of failure. In a bulkhead architecture, elements of an application are isolated into pools so that if one fails, the others will continue to function. It's named after the sectioned partitions (bulkheads) of a ship's hull. If the hull of a ship is compromised, only the damaged section fills with water, which prevents the ship from sinking.

Partition service instances into different groups, based on consumer load and availability requirements. This design helps to isolate failures, and allows you to sustain service functionality for some consumers, even during a failure. A consumer can also partition resources, to ensure that resources used to call one service don't affect the resources used to call another service. For example, a consumer that calls multiple services may be assigned a connection pool for each service. If a service begins to fail, it only affects the connection pool assigned for that service, allowing the consumer to continue using the other services. The benefits of this pattern include:

- Isolates consumers and services from cascading failures. An issue affecting a consumer or service can be isolated within its own bulkhead, preventing the entire solution from failing.

- Allows you to preserve some functionality in the event of a service failure. Other services and features of the application will continue to work.

- Allows you to deploy services that offer a different quality of service for consuming applications. A high-priority consumer pool can be configured to use high-priority services.

Use this pattern to:

- Isolate resources used to consume a set of backend services, especially if the application can provide some level of functionality even when one of the services is not responding.

- Isolate critical consumers from standard consumers.

- Protect the application from cascading failures.

This pattern may not be suitable when:

- Less efficient use of resources may not be acceptable in the project.

- The added complexity is not necessary

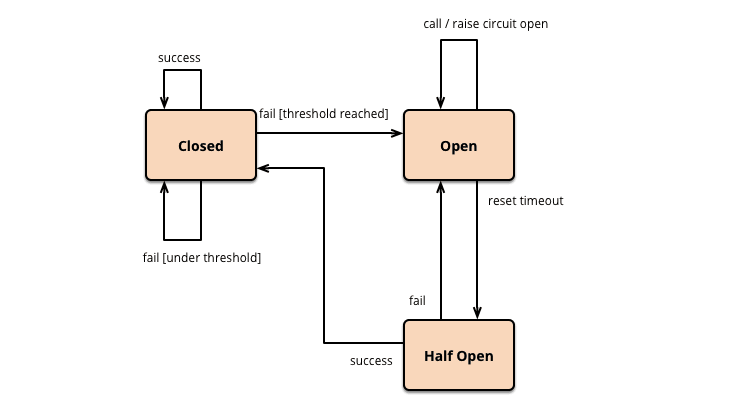

Great for preventing a service failure that could lead to cascading failures throughout the application. A Microservice must request another Microservice through a proxy that works similarly to an Electrical Circuit Breaker. The proxy should count the number of recent failures that have occurred and use that to decide whether to allow the operation to continue or simply return an exception immediately.

The circuit have three states: Closed, Open and Half-Open

Closed The Circuit Breaker forwards requests to the Microservice and counts the number of failures in a given period of time. If the number of failures in a given period of time exceeds a threshold, it trips and goes into the open state.

Open the microservice request fails immediately and an exception is returned. After a timeout, the circuit breaker goes into a half-open state.

Half-Open Only a limited number of Microservice requests are allowed to pass and invoke the operation. If these requests are successful, the circuit breaker will enter the Closed state. If any request fails, the circuit breaker goes into the Open state.

Strong

- Improve fault tolerance and resilience of microservices architecture.

- Stops the cascade of failures for other microservices.

Weak

- Needs sophisticated exception handling.

- Incremental migration of a large Backend Monolithic application to Microservices.

- In large corporations, API Gateway is mandatory to centralize cross-cutting and security concerns.

- Loosely coupled, event-driven microservices architecture.

Rate limiting can reduce your traffic and potentially improve throughput by reducing the number of records sent to a service over a given period of time. A service may throttle based on different metrics over time, such as:

- The number of operations (for example, 20 requests per second).

- The amount of data (for example, 2 GiB per minute).

- The relative cost of operations (for example, 20,000 RUs per second).

Regardless of the metric used for throttling, your rate limiting implementation will involve controlling the number and/or size of operations sent to the service over a specific time period, optimizing your use of the service while not exceeding its throttling capacity. In scenarios where your APIs can handle requests faster than any throttled ingestion services allow, you'll need to manage how quickly you can use the service. However, only treating the throttling as a data rate mismatch problem, and simply buffering your ingestion requests until the throttled service can catch up, is risky. If your application crashes in this scenario, you risk losing any of this buffered data. To avoid this risk, consider sending your records to a durable messaging system that can handle your full ingestion rate. (Services such as Azure Event Hubs can handle millions of operations per second). You can then use one or more job processors to read the records from the messaging system at a controlled rate that is within the throttled service's limits. Submitting records to the messaging system can save internal memory by allowing you to dequeue only the records that can be processed during a given time interval.

- Reduce throttling errors raised by a throttle-limited service.

- Reduce traffic compared to a naive retry on error approach.

- Reduce memory consumption by dequeuing records only when there is capacity to process them.

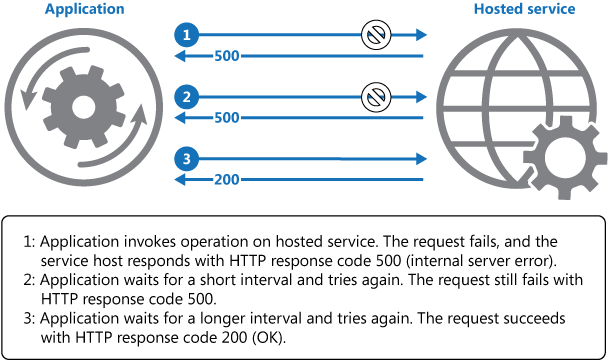

Enable an application to handle transient failures when it tries to connect to a service or network resource, by transparently retrying a failed operation. This can improve the stability of the application.

In the cloud, transient faults aren't uncommon and an application should be designed to handle them elegantly and transparently. This minimizes the effects faults can have on the business tasks the application is performing. If an application detects a failure when it tries to send a request to a remote service, it can handle the failure using the following strategies:

- Cancel. If the fault indicates that the failure isn't transient or is unlikely to be successful if repeated, the application should cancel the operation and report an exception. For example, an authentication failure caused by providing invalid credentials is not likely to succeed no matter how many times it's attempted.

- Retry. If the specific fault reported is unusual or rare, it might have been caused by unusual circumstances such as a network packet becoming corrupted while it was being transmitted. In this case, the application could retry the failing request again immediately because the same failure is unlikely to be repeated and the request will probably be successful.

- Retry after delay. If the fault is caused by one of the more commonplace connectivity or busy failures, the network or service might need a short period while the connectivity issues are corrected or the backlog of work is cleared. The application should wait for a suitable time before retrying the request.

Use this pattern when an application could experience transient faults as it interacts with a remote service or accesses a remote resource. These faults are expected to be short lived, and repeating a request that has previously failed could succeed on a subsequent attempt.

This pattern might not be useful:

- When a fault is likely to be long lasting, because this can affect the responsiveness of an application. The application might be wasting time and resources trying to repeat a request that's likely to fail.

- For handling failures that aren't due to transient faults, such as internal exceptions caused by errors in the business logic of an application.

- As an alternative to addressing scalability issues in a system. If an application experiences frequent busy faults, it's often a sign that the service or resource being accessed should be scaled up.

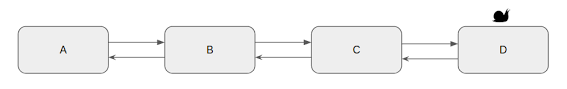

In microservice architecture, one service (A) depends on the other service (B), sometimes due to some network issue, Service B might not respond as expected. This slowness could affect Service A as well as A is waiting for the response from B to proceed further. As it is not uncommon issue, It is better to take this service unavailability issue into consideration while designing your microservices.

The timeout pattern is pretty straightforward and many HTTP clients have a default timeout configured. The goal is to avoid unbounded waiting times for responses and thus treating every request as failed where no response was received within the timeout.

Timeouts are used in almost every application to avoid requests getting stuck forever. Dealing with timeouts is not trivial, however. Imagine an order placement timing out in an online shop. You cannot be sure if the order was placed successfully but the response timed out if the order creation was still in progress, or the request was never processed. If you combine the timeout with a retry, you might end up with a duplicate order. If you mark the order as failed, the customer might think the order didn’t succeed but maybe it did and they will get charged.

- Make the core services work always even when the dependent services are not available

- We do not want to wait indefinitely

- We do not want to block any threads

- To handle network related issues and make the system remain functional using some cached responses.