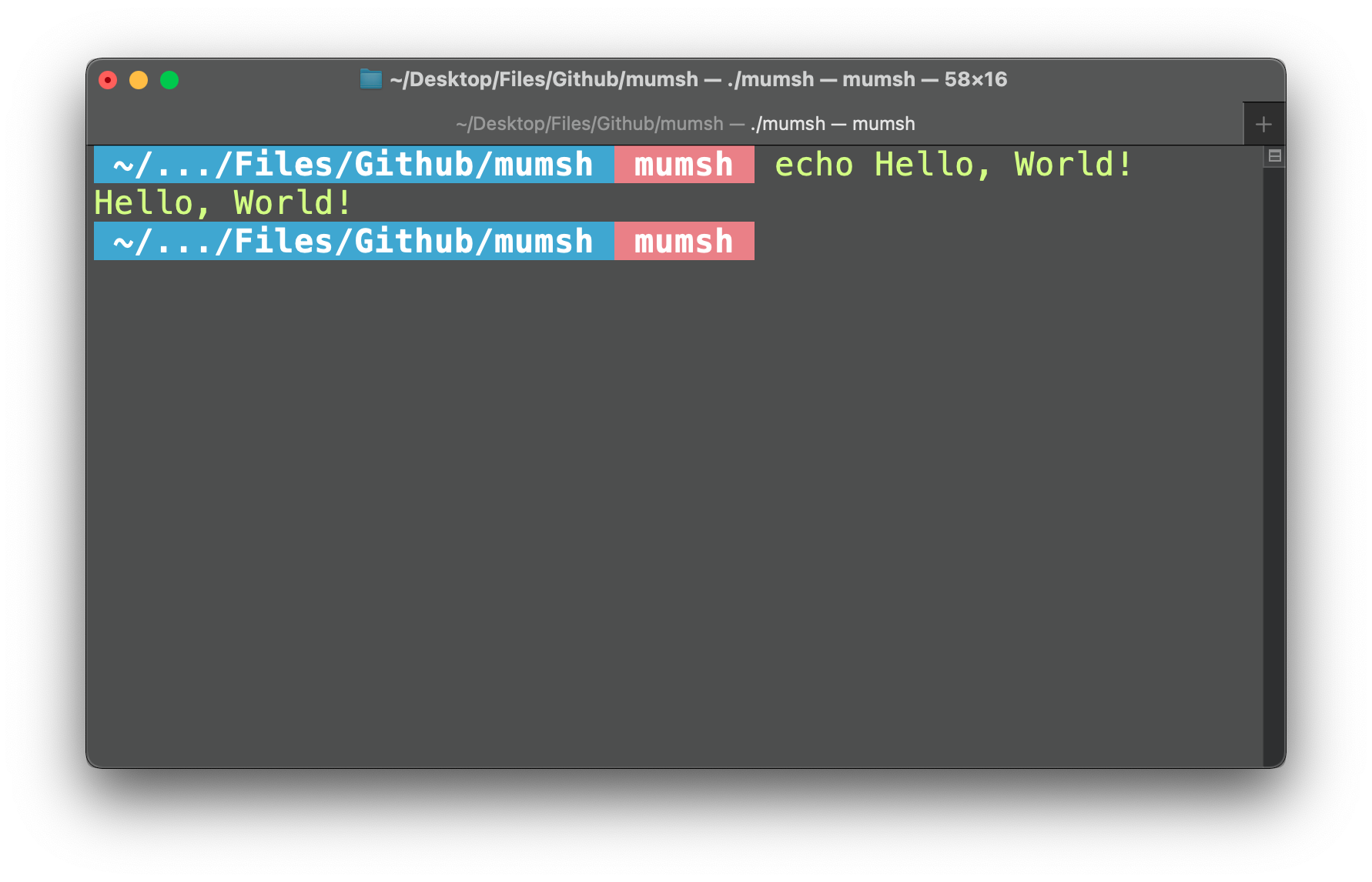

This project is originated from a course project in VE482 Operating System @UM-SJTU Joint Institute. In general, a mini shell called mumsh is implemented with programming language C for Unix-like machine.

For VE482 course project version, see Releases: VE482 Project 1 or Branches: VE482.

-

[2022/2/19] Add feature: Command history auto-completion with smart search

-

[2022/2/15] Add feature: Tab-triggered hint and auto-completion

-

[2022/2/13] Add feature: Left & right cursor switch and dynamic insert & delete

-

[2022/2/12] Add feature: Dynamic current path prompt in prefix

-

Future upgrade list:

- Handle print overflow regarding terminal size

CTRL-Dkeyboard capture and interruption- Show

Gitstatus in prefix - Auto translate

~to home path in parser

mumsh supports some basic shell functionalities including:

- Tab-triggered hint and auto-completion

- Command history auto-completion with smart search

- Incomplete input waiting

- Syntax error handling

- Quotation mark parsing

- Internal commands

exit/pwd/cd/jobs - I/O redirection under

bashstyle syntax - Arbitrarily-deep pipes running in parallel

CTRL-Cinterruption- Background jobs

In this README, the following content will be included:

- What files are related to

mumsh - How to build and run

mumsh - How to play with

mumsh - How to implement

mumsh

We have 4 kinds of files in this project:

- README

- It's strongly adviced to read

README.mdbefore runningmumshor reading source code, since it may give us more sense of whatmumshis doing in each stage.

- It's strongly adviced to read

- C Source files: (in executing order)

mumsh.c: where main read/parse/execute loop ofmumshlocatesio.c: handle reading command line input ofmumshhinter.c: input interface with tab-triggered hint and auto-completionparser.c: parse user input into formatted commands for coming executionprocess.c: execute commands in child process according to specifications

- C header files: (hierarchy from top to bottom)

mumsh.hio.hhinter.hparser.hprocess.h: store global variables regarding processdata.h: store extern global variables regarding read/parse/execute loop

- makefile

- used for quick build and clean of executable files

mumsh is only available on Unix-like machine, as some libraries are not avaiable in Windows.

- build:

$ make - run:

$ ./mumsh

If everything is normal, we can see in the terminal mumsh $ , which indicates that mumsh is up and running, waiting for our input.

Once mumsh is up and running, we can start inputting some commands such as ls or pwd to test the basic functionalities if you have already been familiar to shell.

Of course, mumsh is only a product of a course project supporting basic functions, and yet to be improved. For its detailed ability, please check the following sections.

cmd [argv]* [| cmd [argv]* ]* [[> filename][< filename][>> filename]]* [&]Seems abstract and maybe get a little bit confused? Let me explain a little more.

The input of mumsh can be made up of 4 components:

- command and argument:

cmd,argv - redirector and filename:

<,>,>>,filename - pipe indicator:

| - background job indicator:

&

cmdis a must, ormumshwill raiseerror: missing programargvis optional, we can choose to call a command with arguments or not.

<,>,>>is optional, but we should input redirector along with filename- if any

<, >, |, &instead offilenamefollows,mumshwill raiseerror: syntax error near unexpected token ... - if no character follows,

mumshwill prompt us to keep input in newline

- if any

>and>>can't exist in the same command, ormumshwill raiseerror: duplicated output redirection

|is optional, but we should input|after one command and followed by another command- if no command before

|,mumshwill raiseerror: missing program - if no character after

|,mumshwill prompt us to keep input in newline

- if no command before

|is incompatible with having>or>>before it, and having<after it- if

>or>>comes before|,mumshwill raiseerror: duplicated output redirection - if

<comes after|,mumshwill raiseerror: duplicated input redirection

- if

&is optional, but we should only input&at the end of input, ormumshwill ignore the character(s) after&is detected.

Now, we have our components of input to play with, and we can try it out in mumsh by assembling them into a whole input. As long as mumsh doesn't raise an error, our input syntax is valid, even though this input may give no output.

mumshbuilt-in commandsexit: exitmumshpwd: print working directorycd: change working directoryjobs: print background jobs status

- executable commands (call other programs to do certain jobs)

ls: call program/bin/ls, which print files in current working directorybash: call shell/bin/bash, which is also a shell likemumshbut with more powerful capabilities- we can input

ls /binto see more executable commands

-

Input redirection

< filename: read from file namedfilename, or raise error if nofilenameexists

-

Output redirection

> filename: overwrite if file namedfilenameexists or create new file namedfilename>> filename: append if file namedfilenameexists or create new file namedfilename

-

support bash style syntax

- An arbitrary amount of space can exist between redirection symbols and arguments, starting from zero.

- The redirection symbol can take place anywhere in the command.

- for example:

<1.txt>3.txt cat 2.txt 4.txt

- takes output of one command as input of another command

- basic pipe syntax:

echo 123 | grep 1

- basic pipe syntax:

mumshsupport parallel execution: all piped commands run in parallel- for example:

sleep 1 | sleep 1 | sleep 1only takes 1 second to finish instead of 3 seconds

- for example:

mumshsupport arbitrarily deep “cascade pipes”- for example:

echo hello world | grep h | grep h | ... | grep h

- for example:

-

interrupt all executing commands in foreground with

CTRL-C -

cases:

-

clear user input and prompt new line

mumsh $ echo ^C mumsh $ -

interrupt single executing command

mumsh $ sleep 10 ^C mumsh $

-

interrupt multiple executing commands

mumsh $ sleep 10 | sleep 10 | sleep 10 ^C mumsh $

-

CTRL-C don't interrupt background jobs

mumsh $ sleep 10 & [1] sleep 10 & mumsh $ ^C mumsh $ jobs [1] running sleep 10 & mumsh $

-

-

if

mumshhas no user input,CTRL-Dwill exitmumshmumsh $ exit $ -

if

mumshhas user input, do nothingmumsh $ echo ^D

-

mumshtakes any character between"or'as ordinary character without special meaning.mumsh $ echo hello "| grep 'h' > 1.txt" hello | grep 'h' > 1.txt mumsh $

-

If

&is added at the end of user input,mumshwill run jobs in background instead of waiting for execution to be done. -

Command

jobscan keep track on every background jobs, no matter a job isdoneorrunning -

mumshsupportpipein background jobsmumsh $ sleep 10 & [1] sleep 10 & mumsh $ sleep 1 | sleep 1 | sleep 1 & [2] sleep 1 | sleep 1 | sleep 1 & mumsh $ jobs [1] running sleep 10 & [2] done sleep 1 | sleep 1 | sleep 1 & mumsh $

-

mumshsupport command formattingmumsh $ <'i'n c"a"t| cat |ech'o' "he"llo>out world!& [1] cat < in | cat | echo hello world! > out & mumsh $ jobs [1] done cat < in | cat | echo hello world! > out & mumsh $

In this section, we will go through the construction of mumsh step by step, giving us a general concept of how this shell work. This section is intended for helping beginners (just as me a week ago) grab some basic concept for implementing a shell.

However, some contents such as detailed data structure and marginal logic will be neglected. And the demo code is used for our better understanding instead of doing copy and paste. As a result, the grammar is not strictly follow the C standard. For more detail, we can read the source code directly. It's strongly recommended to understand the concept before doing any coding.

As we all know, a shell is a computer program which exposes an operating system's services to a human user or other program. It repeatedly takes commands from the keyboard, gives them to the operating system to perform and deliver corresponding output.

As a result, the first step for us is to have a main loop, repeatedly doing 4 things:

- prompt

mumsh $ - read user input

- parse input into commands

- execute the commands

int main(){

while(1){

printf("mumsh $ ");

read_user_input();

parser(); // let's call it parser, who parses user input into commands

execute_cmds();

}

}Now we have the basic structure of a shell, but you may notice that it runs forever. As a result, we need a exit-checking funtion in the main loop. If users want to exit the shell, they can just input the command exit and that's it, our shell just exit.

Assume we've already parsed user input into command cmd (we will talk about how to do implement simple parser with Finite State Machinein Section 3.5, we have

void check_cmd_exit(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "exit") == 0) exit(0);

}

int main(){

while(1){

printf("mumsh $ ");

read_user_input();

parser();

check_cmd_exit(); // if user input "exit", exit here

execute_cmds();

}

}You may argue that this exit-checking funtion can be in the part of execute_cmds(). Of course we can do that, but personally I perfer put it in the main loop. And the reason for this is exactly what makes the most important part: how is a command executed in the shell?

First, what is a system call? In Linux manual page, it writes

"The system call is the fundamental interface between an application and the Linux kernel."

Basically, if we want our computer program requests a service from the kernal of the operating system, we use system call.

Just to recap, when we input ls in shell, the shell calls the program /bin/ls. More precisely, the shell asks the kernal of the operating system to execute the program /bin/ls.

To do so, we have to use execvp(), which is a system call under the library <unistd.h>, and it "replaces the current process image with a new process image". When execvp() is executed, the program file given by the first argument will be loaded into the caller's address space and over-write the program there.

For example, once the program we call (e.g. /bin/ls) starts its execution, the original program in the caller's address space (mumsh) is gone and is replaced by the new program (/bin/ls). Here "gone" means our mumsh just somehow vanished, the only program left is /bin/ls. Once /bin/ls finishes its jobs, nothing will be left.

Apparently, this should never happen for a shell to run normally. We still need our shell up and running! As a result, we use another system call: fork().

But before getting into fork(), let's first talk about process.

In Linux, a process is any active (running) instance of a program. But what is a program? Well, technically, a program is any executable file held in storage on your machine.

Aforementioned execvp() system call just replace one program with another in a process, but it doesn't create a new process to make both programs execute at the same time. And here comes the fork() system call.

The fork() system call "creates a new process by duplicating the calling process. The new process is referred to as the child process. The calling process is referred to as the parent process." In this case, if we execute /bin/ls in child process, our mumsh process won't vanish.

Now, we have everything prepared:

- use

fork()system call to create a child process - use

execvp()system call to execute the program in child process

For more detailed documentations, we can check Linux manual page.

fork()- create a child processDescription

- creates a new process by duplicating the calling process

#include <unistd.h> pid_t fork(void);Return value

- On success

- the

PIDof the child process is returned in the parent0is returned in the child- On failure

-1is returned in the parent- no child process is created

errnois set to indicate the error

execvp- execute a filenameDescription

- replaces the current process image with a new process image

#include <unistd.h> int execvp(const char *file, char *const argv[]);Arguments

file: pointer point to the filename associated with the file being executedargv: an array of pointers to null-terminated strings that represent the argument list available to the new program Return value- On success: no return

- On failure

- return

-1if an error has occurrederrnois set to indicate the error

Following the documents, we now can construct the basic fork and execute structure.

void execute_cmds(){

pid_t pid = fork(); // fork() system call

// child and parent process reach here

if (pid == 0) {

// child process starts here

execvp(cmd, argv); // execvp() system call

// child process won't reach here!

} else {

// parent process jumps here

}

}You may ask why the child process can't procceed after execvp(), and that's because execvp() system call have a unique feature: it never return if no error occurs. Basically, it

- replace the program of caller (duplicated instance

mumsh) on child process created byfork()with any program we call - the program we call is up and running in that child process

- the child process terminated as the program finishes its execution

Now that the child process is gone, of course child process will never run the code after execvp(). What only left is the parent process mumsh.

Still remember there's a question left in 3.1.1? Why do I put check_cmd_exit() outside of execute_cmds() in main loop? That's because exit is a built-in command.

void check_cmd_exit(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "exit") == 0) {

exit(0); // exit the parent process

}

}

int main(){

while(1){

read_user_input();

parser();

check_cmd_exit(); // if user input "exit", exit here

execute_cmds();

}

}For normal commands like ls and pwd, our shell execute commands by calling other programs, which happens in the child process after we fork(). However, our exit is a built-in command which we implement ourselves!

Obviously, exit should happen in parent process, because we want to exit mumsh once and for all instead of shutting down a duplicated instance of mumsh running in child process.

Similarly, we can implement command cd (change working directory) as built-in command in parent process. If we accidentally run cd in child process, we change working directory for child mumsh instead of parent mumsh. In that case, nothing changes after child process is exited.

void check_cmd_cd(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "cd") == 0) {

chdir(argv); // chdir() system call

}

}

int main(){

while(1){

read_user_input();

parser();

check_cmd_exit();

check_cmd_cd(); // if user input "cd", change working directory here

execute_cmds();

}

}To be clear, built-in commands are not equal or related to commands run in parent process, they are totally separate things. Here built-in commands are just oppsite to commands that call other programs.

For example, We can still make our built-in commands like pwd running in child process, and it has 2 advantages:

- firstly

pwddoesn't tamper with parent process: it just print something and that's it. Putting it in child process doesn't change its output. - and secondly, if

pwdruns in the child process, we can do more fancy operations such as making it parts of apipeor making it abackground job.

void check_cmd_pwd(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "pwd") == 0) {

getcwd(buffer, BUFFER_SIZE); // getcwd() system call

printf("%s\n", buffer);

exit(0); // in child process now, don't forget to exit!

}

}

void execute_cmds(){

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

check_cmd_pwd(); // if user input "pwd", print working directory here

execvp(cmd, argv);

}

}Until now, the basic structure of mumsh has been constructed.

void check_cmd_cd(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "cd") == 0) {

chdir(argv); // chdir() system call

}

}

void check_cmd_exit(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "exit") == 0) {

exit(0); // exit parent process

}

}

void check_cmd_pwd(){

if (strcmp(cmd, "pwd") == 0) {

getcwd(buffer, BUFFER_SIZE); // getcwd() system call

printf("%s\n", buffer);

exit(0); // exit child process

}

}

void execute_cmds(){

pid_t pid = fork(); // fork() system call

if (pid == 0) { // child process

check_cmd_pwd();

execvp(cmd, argv); // execvp() system call

}

}

int main(){

while(1){

read_user_input();

parser();

check_cmd_exit();

check_cmd_cd();

execute_cmds();

}

}However, there's one more thing to do after we create a child process and run a program on it, which is, monitoring our child process.

To be a qualified parent in real world, we should take care of our children. Let's say we have a child playing badminton on the field, we as parent, have simply 3 choices:

- do nothing and wait for the child until he is done

- do our own stuff and pick the child up after he is done

- do our own stuff and leave the child alone forever

In this metaphor, the child is a child process, the parent is mumsh parent process, and playing badminton is execution of a program. The 3 choices are correspondingly:

- parent process is

blockedtowaitthe child process toexit - parent process is

unblockedandwaitthe child process toexitsometime in future - parent process is

unblockedand don't give a sh*t about the status of child process

Apparently, our mumsh is a caring parent, so we should choose option 1 or 2.

In both options, we say the child process is reaped by the parent process, and the only difference is we wait blockingly or not when the child process is executing.

To make us a good parent, waitpid() system call is needed.

waitpid()- wait for process to change stateDescription

- Suspends execution of the calling thread until a child specified by pid argument has changed state

#include <sys/wait.h> pid_t waitpid(pid_t pid, int *wstatus, int options);Arguments

pid

> 0: wait for the child whoseprocess IDis equal to the value ofpid0: wait for any child process whoseprocess group IDis equal to that of the calling process at the time of the call towaitpid()-1: wait for any child process< -1: wait for any child process whoseprocess group IDis equal to theabsolute value of pidwstatus:int pointerpointing to theintthat stores status informationoptions

0: by default, waits only for terminated childrenWNOHANG: return immediately if no child has exitedWUNTRACED: also return if a child has stopped...Return value

- On success

- the

PIDof the child process is returned in the parent0is returned in the child- On failure

-1is returned in the parent- no child process is created

errnois set to indicate the error

Following the document, with waitpid system call and WUNTRACED argument, we now can construct the complete fork-execute-wait structure.

void execute_cmds(){

pid_t pid = fork(); // fork() system call

if (pid == 0) { // child process

check_cmd_pwd();

execvp(cmd, argv); // execvp() system call

}

// parent wait here until child exit or interrupted

waitpid(pid, NULL, WUNTRACED);

}Tips: command sleep is useful to observe blocking. Try sleep 5 for sleeping 5 seconds!

Similarly, with waitpid system call and WNOHANG argument, if a child died, its pid will be returned, and if nothing died, then 0 will be returned. In both case, waitpid will run and return immediately instead of waiting blockingly.

In mumsh, mumsh will try to reap all background processes within function reap_background_jobs() once users trigger a next input by pressing ENTER or interrupt with CTRL-C. For more details regarding background jobs handling, please refer to Section 3.6. The sample code is given as followed:

void reap_background_jobs(){

// try to reap all background processes no matter running or done

for (size_t i = 0; i < background_jobs_count; i++){

waitpid(-1, NULL, WNOHANG); // reap only dead child process

}

}In Section 3.2, we assumed that we already parsed user input into command cmd and execute. Now, it's time for us to implement a parser for real!

(If you are currently a VE482 student, I suggest you to start early on milestone 1 and put more attentions on parser. Without a properly-organized parser, you would suffer a lot from refactoring your code in the future milestones)

The command formats are mentioned in Section 2.1, please check first if you are not familar with the concept.

Task:

-

Given a

simple commandbelow, please describe in what ways our brain is parsing the commandsecho hello < 1.in world > 1.out &

-

Given a

cascade commandbelow, please describe in what ways your brain is parsingecho hello world | cat | cat | cat | grep hello

-

Given a

complicated commandbelow, please describe in what ways our brain is parsing"echo" hello' < "'world'" | 'cat > '3.out'

Please think for yourself first and then check whether it matches the following strategies:

- Searching for keywords

>,<, then check the first cluster after it - Searching for whitespace to separate arguments in left and right

- Searching for

|to separate commands in left and right - Searching for

",'and another quotes close to each other

Unfortunately, if you choose any of the strategy listed above, you might be on a wrong track.

Our brain indeed works fast on identifying keywords like <,>,| or separating arguments by whitespace in the middle, however, they might have no meaning in a command.

For example,

echo hello ">" 1.out < 1.injust printhello > 1.outon the screen instead of doing output redirectionecho "hello' 'world"only print one argumenthello' 'worldinstead ofhelloandworld

As a result, it doesn't work if we are trying to match something in the middle of a command, at least for supporting quotes. And here comes our savior: Finite State Machine.

(If you are a JI student, you should be familiar with FSM at least in VE270!)

According to Google searching results, A Finite State Machine, or FSM, is

a computation model that can be used to simulate sequential logic, or, in other words, to represent and control execution flow. Finite State Machines can be used to model problems in many fields, including mathematics, artificial intelligence, games or linguistics.

From above descriptions, the most important term is simulate sequential logic, which means, we start from the leftmost character and read one by one to the rightmost character.

For above command echo hello ">" 1.out < 1.in, please follow the steps:

- we read in

eand we write on paper: we havee - we read in

cand we write on paper: we haveec - we read in

hand we write on paper: we haveech - we read in

oand we write on paper: we haveecho

Here comes the critical part,

- we read in

white space, and we say: "Nice!echois the first argument".

But wait, some critical questions comes:

- How do you know the

echois the whole string? - Can we have

white spacein a command? Perhaps the first command is something likeecho twice? - How do you know the

echois the argument? - Can

echobe a redirection filename?

The answer is obvious, we haven't meet ', " and >, >>, < yet. If I have implemented a built-in command, which is called echo twice, then user should input "echo twice" in command line instead of echo twice, otherwise, twice will be treated as argument and echo will be treat as command. If echo is filename, then we must have meet a redirector.

For now, we can conclude some useful knowledge

- every character including

whitespaceis an ordinary character without special meaning between quotes whitespaceindicate the end of a argument outside of quotes- If we don't meet a

redirector, then the string is an argument.

(The command to parse: echo hello ">" 1.out < 1.in)

Back to step 5, our question is solved, echo indeed is the first argument. As we keep moving, similarly, we can find

hellois the second argument.

After that, we read a double quote ", with above knowledge, you say:" Aha! I meet a double quote, let's just keep reading every characters until I meet another double quote"". As a result, we know

- a single char

>as the third argument

As we keep moving, since no "true" redirector has been meet, we know

1.outis the fourth argument

Suddenly, we read in a < and you say:" Aha! Last two quotes are matched! We are outside of quotation marks." As a result,

<is a sign ofinput redirection.

According to the grammars, we need a filename to perform redirection. So you take a note on the paper: "I need a filename." Now, whatever we read in next is a filename instead of a argument. Then, we find 1.in, and we know

1.inis afilenameforinput redirection.

Finally, we read in \n, which is the newline inputted by pressing ENTER in keyboard, indicating our parsing process comes to an end... or... maybe not?! Consider following cases, what if the command is imcomplete:

- The quotation marks are not closed? e.g.

echo "hello - No

filenameafter<or>outside the quotes? e.g.echo hello > - No

argumentafter|outside the quotes? e.g.echo hello |

Or what if... we have a rookie user who is messing up with our input with wrong grammar:

- Syntax error: e.g.

echo > < - Duplicated output direction: e.g.

echo > out | cat - Missing program: e.g.

| cat - ......

Actually, the answer to the questions are all hiden in FSM. For FSM, we have different states to jump from one another according to the condition. Here condition is defined by the character we meet now, and states are defined as different roles toward a character. Once we find some unexpected behaviors which are not defined in our FSM, then we raise an error.

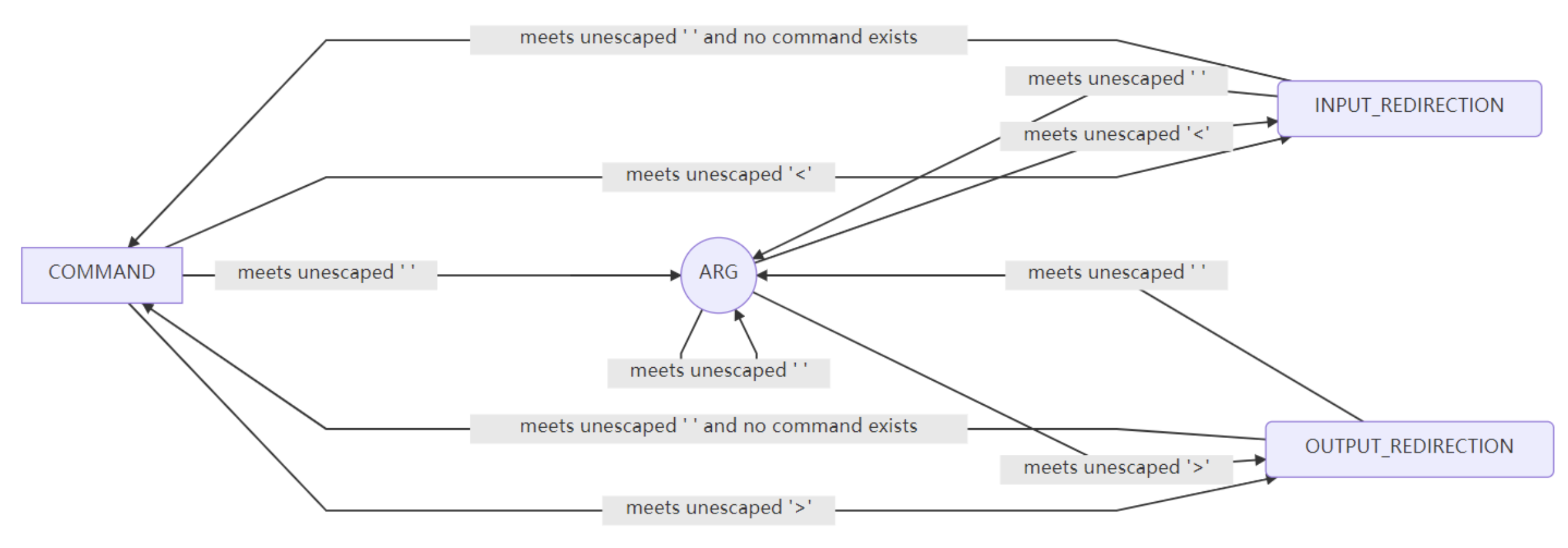

For reference, the following FSM defines states and state transitions of a simple strong parser.

You may notice that the pipe mark | and background jobs indicator & are absent in the above FSM. But once we figure this methodology out, it's nothing big deal but adding a few state transitions.

Commonly, we can use while loop together with switch case to switch states of FSM. However, for mumsh, we use for loop with if else branch to switch conditions. Both of the implementation can serve the needs of a FSM parser.

(Considering code reuse, the source code of mumsh is a little bit different from the following demo structure.)

extern char user_input[BUFFER_SIZE];

void parser(){

for (size_t i = 0; i < BUFFER_SIZE; i++) {

if (FSM.in_quotation){

if (user_input[i] == '\''){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '\"'){

// do something and switch state

} else {

// do something and switch state

}

} else {

if (user_input[i] == ' '){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '<'){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '>'){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '|'){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '\''){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '\"'){

// do something and switch state

} else if (user_input[i] == '&'){

// do something and switch state

} else {

// do something and switch state

}

}

}

}In mumsh, we keep the state and condition information in a parser struct, which is used as a local variable in parser():

typedef struct parser {

size_t buffer_len; // char buffer length

int is_src; // input redirection state

int is_dest; // output redirection state

int is_pipe; // in pipe condition indicator

int in_single_quote; // in single quote condition indicator

int in_double_quote; // in double quote condition indicator

char buffer[BUFFER_SIZE]; // char buffer

} parser_t;In mumsh, we save the command-related information in a cmd struct, which is used as an external global variable in various such as execute_cmds() and check_cmd_xx() :

typedef struct token {

size_t argc; // argument count

char* argv[TOKEN_SIZE]; // argument list

} token_t;

typedef struct cmd {

size_t cnt; // command count

int background; // background job indicator

int read_file; // input redirection indicator

int write_file; // output redirection indicator

int append_file; // append mode indicator

char src[BUFFER_SIZE]; // input redirection filename

char dest[BUFFER_SIZE]; // output redirection filename

token_t cmds[COMMAND_SIZE]; // command list

} cmd_t;

extern cmd_t cmd;In Section 3.4.4, we briefly talk about the mechanism of reaping background process, which is trying to reap all background processes within function reap_background_jobs() once users trigger a next input by pressing ENTER or interrupt with CTRL-C.

To implement built-in command jobs, we have to design a more reasonable data structure to:

- store the input commands ended with

& - store whether a background process is running or done

Also, this data structure should be flexible in size, because in this project, all the previous background jobs status should be printed out by jobs command. And here comes our job table, implemented by struct job, which type name is job_t.

#define JOBS_CAPACITY 1024 // job table capacity

typedef struct job {

size_t bg_cnt; // number of processes running in background

size_t job_cnt; // number of all background processes

size_t table_size; // size of job table

size_t* stat_table; // status of a background command

pid_t** pid_table; // table of all background process ID

char** cmd_table; // table of all formatted background command

} job_t;For example, in the following cases,

mumsh $ sleep 10 | sleep 10 &

[1] sleep 10 | sleep 10 &

mumsh $ sleep 1 &

[2] sleep 1 &

mumsh $ jobs

[1] running sleep 10 | sleep 10 &

[2] done sleep 1 &-

bg_cnt = 2 -

job_cnt = 3 -

table_size = 2 -

stat_tableindex status [1] running[2] done -

pid_tableindex pid pid [1] 8810088101[2] 88102 -

cmd_tableIndex Command [1] sleep 10 | sleep 10 &[2] sleep 1 &

With this job table data structure, we can easily handle the background jobs.

In this section, we are going to build the redirection and pipe using dup2() and pipe() system call.

The nature of redirection and pipe is actually the same: the direction of input and output stream are changed:

- With a redirection, the

stdinorstdoutchanges to a file - With a pipe, the

stdoutof the former command becomes thestdinof the latter command.

To do this, we should first get familiar with file desciptor.

According to Wikipedia,

A file descriptor (FD) is a unique identifier (handle) for a file or other input/output resource. File descriptors typically have non-negative integer values, with negative values being reserved to indicate "no value" or error conditions.

For each process, 3 standard file descriptors are given, corresponding to the 3 standard streams:

| Integer value | Name | <unistd.h> symbolic constant |

<stdio.h> file stream |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Standard input | STDIN_FILENO |

stdin |

| 1 | Standard output | STDOUT_FILENO |

stdout |

| 2 | Standard error | STDERR_FILENO |

stderr |

With the knowledge of file desciptor, what if we adjust the original file desciptor so that it now refers to a new open file?

For example, if we change stdout file desciptor to let it represent a specified file, the output stream will be redirected to this specified file instead of stdout, and that's how dup2() system call works.

dup2()- duplicate a file descriptorDescription

- The

dup2()system call allocates a new file descriptornewfdthat refers to the same open file description as the descriptoroldfd#include <unistd.h> int dup2(int oldfd, int newfd);Arguments

newfd: new file descriptor to be allocatedoldfd: old file descriptor to be referredReturn value

- On success: return the new file descriptor

- On failure

-1is returnederrnois set to indicate the error

For the pipe, the case is a little bit more complicated. We can't just dup2(STDIN_FILENO, STDOUT_FILENO), because it works only for one process, and it makes no sense making my output to my input.

As a result, we need something serving as an "intermediate" between two processes for data transfer. Here comes the pipe and pipe() system call.

pipe()- create pipeDescription

pipe()creates a pipe, a unidirectional data channel that can be used for interprocess communication- Data written to the write end of the pipe is buffered by the kernel until it is read from the read end of the pipe.

#include <unistd.h> int pipe(int pipefd[2]);Arguments

- The array

pipefdis used to return two file descriptors referring to the ends of the pipe:

- pipefd[0] refers to the read end of the pipe

- pipefd[1] refers to the write end of the pipe

Return value

- On success: zero is returned

- On failure

-1is returnederrnois set to indicate the errorpipefdis left unchanged

The rest of the coding is really simple:

-

First, we create an array storing file descriptor for each process

int pipe_fd[PROCESS_SIZE][2]; // store pipe file descriptor for piping

-

Second, for each process, connect the previous and next with pipe:

- For the left pipe

i-1:- Close the wirte end

- adjust

stdinto the read end

- For the right pipe

i- close the read end

- adjust

stdoutto the write end.

Below is the sketch and code for better understanding.

[process i-1] -> {write end <- pipe i-1 -> read end} <- [process i] -> {write end <- pipe i -> read end} <- [process i+1] -> ...

#define READ_END 0

#define WRITE_END 1

// pipe at the left of the current command

close(pipe_fd[i - 1][READ_END]);

dup2(pipe_fd[i - 1][READ_END], STDIN_FILENO);

// pipe at the right of the current command

close(pipe_fd[i][READ_END]);

dup2(pipe_fd[i][READ_END], STDOUT_FILENO);