A C++ implementation of karpathy/makemore, a toy system for generative AI.

Over a series of videos, episodes 2-5 of Neural Nets: Zero to Hero, Andrej Karpathy details how to build a simple generative model. This repository follows the thread of these videos, with the aim of developing a corresponding platform in C++. This platform includes reusable code for:

- building larger models that can be trained via backpropagation

- visualization of matrices and plots of training data

- training and sampling from models

These steps are essential for doing research on neural nets, so that the full cycle of trying out ideas and evaluating them can be done with a few lines of code.

Building micrograd spelled out backpropagation and training of neural nets. I implemented a C++ version of that in kfish/micrograd-cpp-2023.

This repository (makemore-cpp-2023) continues on from there, expanding the automatically

differentiable Value<T> object to use vector and matrix operations.

This extension is crucial for applying automatic differentiation in a broader context.

Each step of the second episode of Neural Nets: Zero to Hero: The spelled-out intro to language modeling: building makemore is included.

makemore "makes more of things like what you give it". What it generates is unique names, made from sequences of characters, one letter at a time. It is trained on a large list of common names, names.txt.

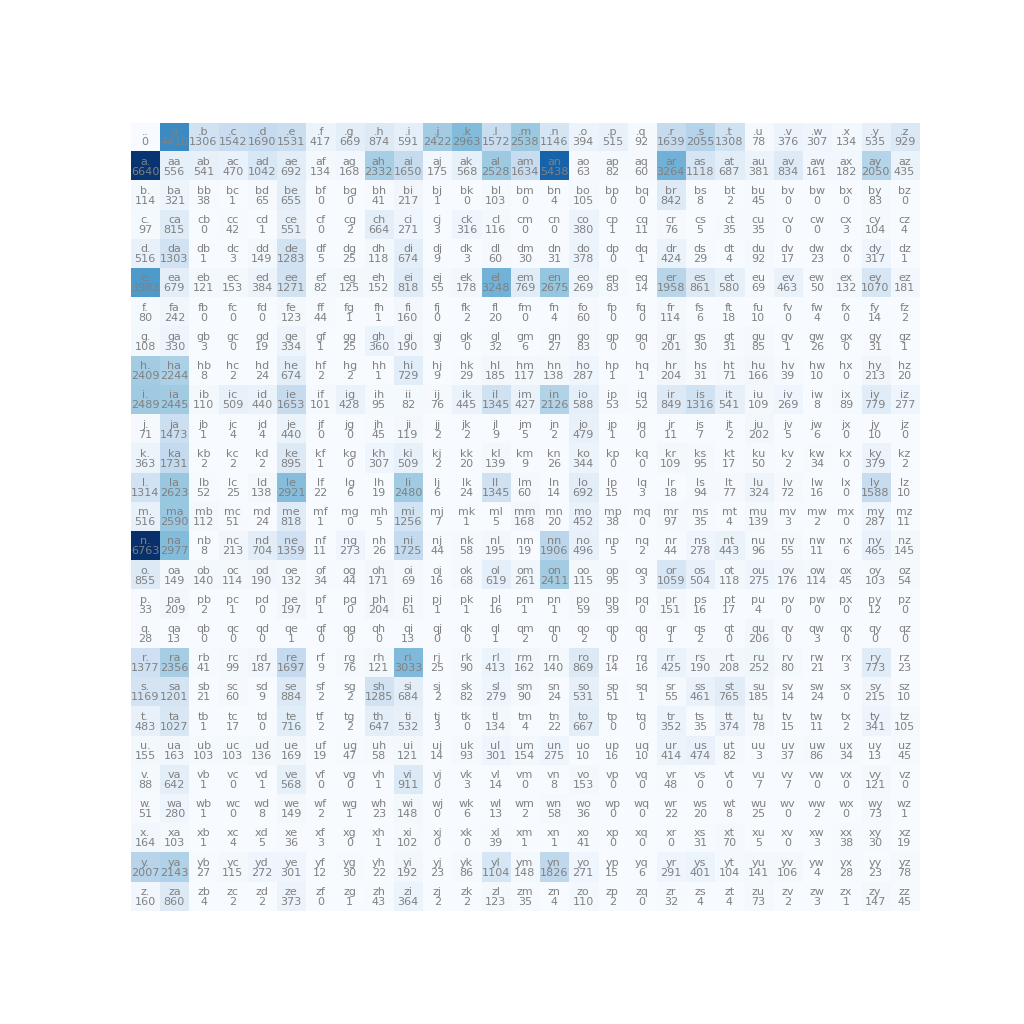

To demonstrate the concept of building a model, training and evaluating it, we first make a complete statistical model by counting often each pair of letters occurs.

We then replace the model itself with a neural network, and tweak that.

A bigram is a pair of "grams", which are grammatical dust, the smallest written things. In this toy system we use individual letters, so our bigram model looks at pairs of letters.

The code in examples/bigram.cpp constructs a Bigram Language Model, renders the table, and generates new names.

We start by counting how often each pair of letters occurs:

For example 4410 names start with the letter a , which we can prove to ourselves with grep:

$ grep -c ^a names.txt

4410We can think of each row of the matrix as telling us what the likelihood of the next letter is. The top row

tells us the likelihood of the first letter in a name (a is more likely than u).

If we chose an a, the next letter is very likely to be n or l, and unlikely to be q or o.

We'll start with some code to put the frequencies of each pair ("bigram") into a matrix, and display that.

We're going to need to manipulate matrices of numbers. We won't need to do complex linear algebra here but it is useful to be able to select rows and columns of numbers and apply logs and exponents to everything. When we build out the neural net we'll do some matrix multiplications and transposes.

Eigen is a high-level C++ library for linear algebra, matrix and vector operations. It can make use of vectorized CPU instructions so it's efficient enough to get started.

matplotlib-cpp is a C++ wrapper around the Python matplotlib library. This allows us to use the same visualizations that the machine learning community uses for research.

I've forked matplotlib-cpp with some small changes required: kfish/matplotlib-cpp

In order to use this, you'll need to install some Python development packages, required for linking C/C++ code against a Python interpreter:

$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt install python3 python3-dev python3-matplotlibNote

Python will only be used for visualization: the core neural net training and sampling is all implemented in C++.

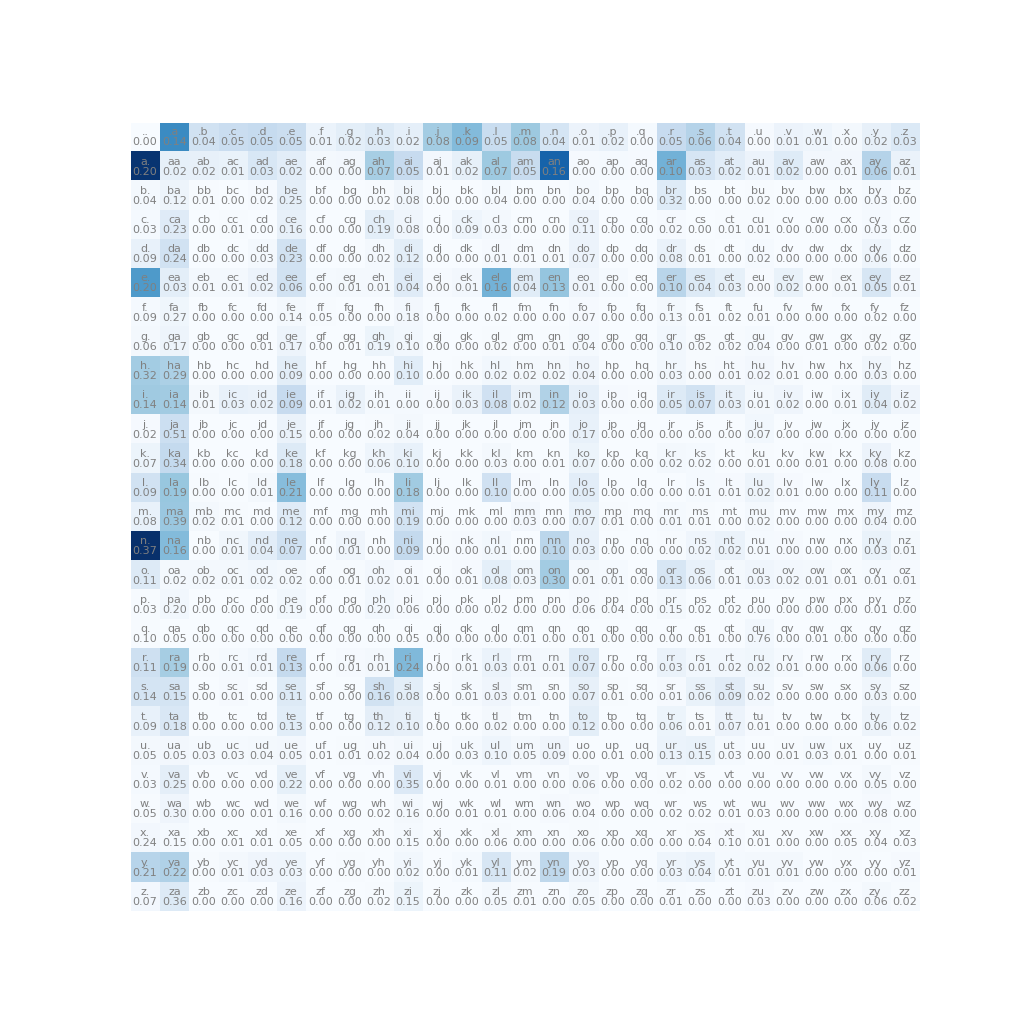

We normalize (ie. divide by the sum of) each row to calculate the probability of subsequent letters:

Eigen::MatrixXd generate_probability_distributions(const Eigen::MatrixXd& freq_matrix) {

Eigen::MatrixXd prob_matrix = freq_matrix; // Copy the matrix; will modify in place

Eigen::VectorXd row_sums = freq_matrix.rowwise().sum(); // Sum along each row

// Normalize each row

for (int i = 0; i < freq_matrix.rows(); ++i) {

if(row_sums(i) > 0) { // Guard against division by zero

prob_matrix.row(i) /= row_sums(i);

}

}

return prob_matrix;

}and use matplotlib-cpp to generate a table of probabilities:

plt::figure_size(1024, 1024);

plt::imshow(bigram_freq, {{"cmap", "Blues"}});

for (int i=0; i<27; ++i) {

for (int j=0; j<27; ++j) {

char label[3] = {i_to_c(i), i_to_c(j), '\0'};

plt::text(j, i, label, {{"ha", "center"}, {"va", "bottom"}, {"color", "grey"}, {"fontsize", "8"}});

double v = prob_matrix(i, j);

std::string value = static_cast<std::ostringstream&&>(std::ostringstream() << std::fixed << std::setprecision(2) << v).str();

plt::text(j, i, value, {{"ha", "center"}, {"va", "top"}, {"color", "grey"}, {"fontsize", "8"}});

}

}Finally we want to generate names. We do this by choosing each letter in turn, with likelihood given by the previous letter's row of the probability matrix.

We interpret the row as a probability distribution and sample from that. The C++ standard library provides some basic types for random number generation and using probability distributions, in particular we use std::discrete_distribution.

class MultinomialSampler {

private:

std::vector<std::discrete_distribution<int>> distributions; // Cached distributions

std::mt19937 rng; // Random number generator

// Cache discrete_distribution instances for each row of the probability matrix

void cache_distributions(const Eigen::MatrixXd& prob_matrix) {

for (int i = 0; i < prob_matrix.rows(); ++i) {

Eigen::VectorXd row = prob_matrix.row(i); // Force evaluation into a dense vector

std::vector<double> prob_vector(row.data(), row.data() + row.size());

std::discrete_distribution<int> dist(prob_vector.begin(), prob_vector.end());

distributions.push_back(dist);

}

}

public:

// Constructor that takes a precalculated probability matrix

MultinomialSampler(const Eigen::MatrixXd& prob_matrix)

: rng(static_mt19937())

{

cache_distributions(prob_matrix);

}

// Operator to sample given a row index

size_t operator()(size_t row_idx) {

if (row_idx >= distributions.size()) {

throw std::out_of_range("Row index out of bounds");

}

// Use the pre-cached distribution to sample and return column index

return distributions[row_idx](rng);

}

};Finally we can use this MultinomialSampler to generate names:

auto multinomial = MultinomialSampler(prob_matrix);

auto generate = [&]() {

int ix = 0;

do {

ix = multinomial(ix);

std::cout << i_to_c(ix);

} while (ix);

std::cout << std::endl;

};

for (int i=0; i<50; ++i) {

generate();

}Which generates some new names:

$ examples/bigram ../names.txt

xsia.

atin.

yn.

cahakan.

eigoffi.

la.

wyn.

ana.

k.

tan.

...

We'd like to improve on this when we use a more complex model, and in order to do that we need to be able to evaluate how good a model is and the contribution of each model parameter.

We invent a function that returns a number representing how bad the model is. If we can tweak our parameters so that this number goes down, then we think we've improved our model. This is loss.

The loss function compares our model output to the expected values: here, our model outputs a probability distribution for each subsequent letter, and we can compare the actual input data from names.txt and look up the probability that our model would have picked each letter in turn.

For a good model we want the probabilities to be as high as possible. We could combine them all by multiplying them together; let's pretend we're doing that but first take the log of each value so we can just add the logs (instead of multplying the original values) to get a result that improves similarly but is easier to calculate.

Lastly we want to average out this value so it's independent of the number of samples, and negate it so that smaller is better. We call the result the negative log-likelihood.

while (file >> word) {

int prev_index = 0;

for (char c : word) {

c = std::tolower(c);

if (c < 'a' || c > 'z') continue;

int curr_index = c_to_i(c);

log_likelihood += log(prob_matrix(prev_index, curr_index));

++n;

prev_index = curr_index;

}

log_likelihood += log(prob_matrix(prev_index, 0));

++n;

}

double nll = -log_likelihood / (double)n;Tip

Broadcasting rules refer to the automatic expansion of matrices or vectors to compatible sizes during operations.

Eigen requires you to be explicit about which dimensions you are replicating using .colwise() or .rowwise(),

so there is little chance of surprising errors. For details see the Eigen documentation,

Reductions, visitors and Broadcasting.

We will gradually replace the bigram model with a neural net. Step by step:

- Encode the letters in a way that works with neural nets

- Build a simple neural net using

Value<T>from kfish/micrograd-cpp-2023 - Replace the data representation with

Eigen::MatrixXd - Explore optimization techniques

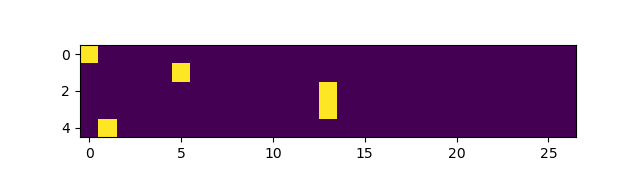

The input to a neural net needs to be a set of numbers. Rather than using some preconceived encoding like ASCII, let's start with the most senseless representation and let the AI make sense of it.

To encode a single letter we'll use 27 separate values and set them all to zero except one. This is called onehot encoding.

static inline Eigen::VectorXd encode_onehot(char c) {

return OneHot(27, c_to_i(c));

}

static inline Eigen::MatrixXd encode_onehot(const std::string& word) {

Eigen::MatrixXd matrix(word.size(), 27);

for (size_t i = 0; i < word.size(); ++i) {

matrix.row(i) = encode_onehot(tolower(word[i]));

}

return matrix;

}

We can encode the input string ".emma" (including start token '.')

and visualize this to make it a little more clear:

std::string xs = ".emma";

auto xenc = encode_onehot(xs);

plt::figure_size(640, 180);

plt::imshow(xenc);First we implement a simple "neural net" using the Value<T> we developed in

kfish/micrograd-cpp-2023.

Here we model each neuron individually as LogitNeuron<double, 27>:

- each neuron keeps an array of 27

weights_ - each neuron gets all 27 input values

- inputs are multiplied with their corresponding weights, and these are summed (accumulated)

macis the multiply-accumulate of all weights and inputs- we then take the

expof the result to get a positive "logit" count

template <typename T, size_t Nin>

class LogitNeuron {

public:

LogitNeuron()

: weights_(randomArray<T, Nin>())

{}

Value<T> operator()(const std::array<Value<T>, Nin>& x) const {

Value<T> zero = make_value<T>(0.0);

Value<T> y = mac(weights_, x, zero);

return expr(exp(y), "n");

}

void adjust(const T& learning_rate) {

for (const auto& w : weights_) {

w->adjust(learning_rate);

}

}

private:

std::array<Value<T>, Nin> weights_{};

};We then use 27 of these neurons in a LogitLayer<double, 27, 27>, which:

- sends the same input to all 27 neurons

- normalizes the output so the results sum to 1.0, so we can interpret it as a probability distribution

template <typename T, size_t Nin, size_t Nout>

class LogitLayer {

public:

std::array<Value<T>, Nout> operator()(const std::array<Value<T>, Nin>& x) const {

std::array<Value<T>, Nout> counts;

std::transform(std::execution::par_unseq, neurons_.begin(), neurons_.end(),

counts.begin(), [&](const auto& n) { return n(x); });

return norm(counts);

}

void adjust(const T& learning_rate) {

for (auto & n : neurons_) {

n.adjust(learning_rate);

}

}

private:

std::array<LogitNeuron<T, Nin>, Nout> neurons_{};

};This all works but it is very inefficient:

- each weight is stored as a

Value<double>object with its own gradient - each of the 27x27 multiplies and additions creates a new

Value<T>with a backward pass - normalizing the output requires another 27 additions and a division, each being a new

Value<T>with a backward pass

Next we develop a Node class using Eigen matrices. The code for this is in include/node.h.

For example, matrix multiplication has a backward pass which is analagous to the scalar case, where each operand's gradient depends on the other operand:

friend ptr operator*(const ptr& a, const ptr& b) {

auto out = make_empty(a->rows(), b->cols());

out->prev_ = {a, b};

out->op_ = "*";

out->forward_ = [](NodeValue* out) {

const ptr& a = out->prev_[0];

const ptr& b = out->prev_[1];

out->data() = a->data() * b->data();

};

out->backward_ = [](NodeValue* out) {

ptr& a = out->prev_[0];

ptr& b = out->prev_[1];

a->grad() += out->grad() * b->data().transpose();

b->grad() += a->data().transpose() * out->grad();

};

out->forward_(out.get());

return out;

}Operations such as exp() and tanh() are handled element-wise, and operations like

normalize_rows() are more involved bulk operations.

friend ptr normalize_rows(const ptr& a) {

auto out = make_empty_copy(a);

out->prev_ = {a};

out->op_ = "normalize_rows";

out->forward_ = [](NodeValue* out) {

const ptr& a = out->prev_[0];

// Calculate the sum of each row

Eigen::VectorXd rowSums = a->data().rowwise().sum();

// Use broadcasting for normalization

for (int i = 0; i < a->data().rows(); ++i) {

if (rowSums(i) != 0) { // Avoid division by zero

out->data().row(i) = a->data().row(i).array() / rowSums(i);

}

}

};

out->backward_ = [](NodeValue* out) {

ptr& a = out->prev_[0];

int rows = a->data().rows();

int cols = a->data().cols();

for (int i = 0; i < rows; ++i) {

double rowSum = a->data().row(i).sum();

double rowSumSquared = rowSum * rowSum;

for (int j = 0; j < cols; ++j) {

double grad = 0.0;

for (int k = 0; k < cols; ++k) {

if (j == k) {

grad += out->grad()(i, k) * (1 / rowSum - a->data()(i, j) / rowSumSquared);

} else {

grad -= out->grad()(i, k) * a->data()(i, k) / rowSumSquared;

}

}

a->grad()(i, j) += grad;

}

}

};

out->forward_(out.get());

return out;

}This allows us to replace the LogitNeuron and LogitLayer with a single LogitNode<27, 27> class:

- All weights are stored in a 27x27 matrix, in a

Nodeobject - Each row of the matrix represents one neuron

- The computational graph is much simpler, as there is just one operation to multiply the input vector against the weight vector

- The backward pass is a shorter sequence of operations to calculate gradients for matrix multiplication, exponentiation and row normalization

template <size_t N, size_t M>

class LogitNode {

public:

LogitNode()

: weights_(make_node(Eigen::MatrixXd(N, M)))

{}

Node operator()(const Node& input) const {

// input is a column vector; transpose it to a row vector to select a row of weights_

return normalize_rows(exp(transpose(input) * weights_));

}

void adjust(double learning_rate) {

weights_->adjust(learning_rate);

}

private:

Node weights_;

}; build$ examples/logit-node-backprop ../names.txt

Model: 729 params

Calculated loss=0x55b6d3a5ea20=&NodeValue(label=, data=-751931.99763405, grad=0.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=+)

Read n=228146 bigrams

nll: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=3.29583687, grad=0.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

nll: 31484880 params

Iter 0: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=3.29583687, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 1: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=3.05087721, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 2: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.90542885, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 3: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.81752616, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 4: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.75688583, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 5: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.71314887, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 6: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.68049846, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 7: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.65527269, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 8: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.63518461, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 9: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.61878539, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 10: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.60512778, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

...

Iter 290: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45912979, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 291: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45911045, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 292: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45909124, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 293: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45907217, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 294: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45905323, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 295: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45903443, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 296: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45901575, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 297: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45899721, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 298: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45897879, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Iter 299: 0x55b6d3a5edb0=&NodeValue(label=, data=2.45896050, grad=1.00000000, dim=(1, 1), op=/)

Incentivize the weights matrix to be near zero: add the average of the squared weight values to the loss function:

- auto nll = -loss / n;

+ auto nll = -loss / n + 0.01 * mean(pow(f.weights(), 2.0));We can extract the probability matrix for all possible outputs

Eigen::MatrixXd extract_probability_matrix(const LogitNode<27, 27>& layer) {

Eigen::MatrixXd prob_matrix = Eigen::MatrixXd::Zero(27, 27);

for (size_t row=0; row < 27; ++row) {

Node output = layer(onehots[row]);

for (size_t col=0; col < 27; ++col) {

prob_matrix(row, col) = output->data()(col);

}

}

return prob_matrix;

}And sample from it using our MultinomialSampler:

auto prob_matrix = extract_probability_matrix(layer);

auto multinomial = MultinomialSampler(prob_matrix);

auto generate = [&]() {

int ix = 0;

do {

ix = multinomial(ix);

std::cerr << i_to_c(ix);

} while (ix);

std::cerr << std::endl;

};

for (int i=0; i<50; ++i) {

generate();

}Generating nearly the same names.

xph.

batin.

yn.

cahakan.

eigoffi.

la.

wyn.

ana.

k.

tan.

The machine learning lesson here is in Karpathy's video. We used that to motivate the develpment of some C++ code.

We introduced a simple bigram model, and how to evaluate it. Then we replaced the bigram model with a neural network, and trained it to achieve similar results. We also explained some simple smoothing regularization. Along the way we used matplotlib-cpp to visualize the bigram frequencies and the onehot encoding.

It looks like we're working towards a hackable framework for developing and exploring machine learning ideas in C++.