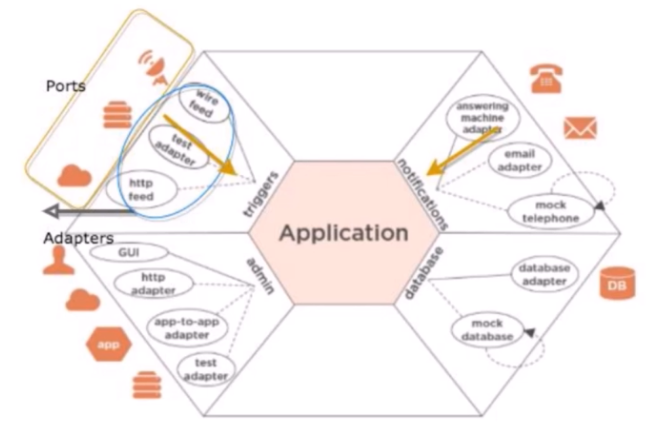

Called Ports and adapters too, it is Architecure design pattern. Is a bigpicture about design of software. It is too a guideline, understanding the benefits. The focus are business requirements, trying to delay technical decisions, following agile principles. The goal is create a sofware that can be excute for users, programs or tests, providing a good enviroment to isolation test.

The main concept is isolation. We can separe the architecture in three blocks or areas:

- The center of the hexagon

- Left side, outside of the hexagon

- Right side, outside of the hexagon

Inside, we have the business rules, all logic of the solution. The center must to be agnostic for technology, intrastructure or famework, exceptions like log or IoC.

Left side, we have the external actors to trigger events on our software. Rest, UI, etc.

Right side, we have stuffs about infrastructure, that means call HTTP, filesystem, database, etc.

Outside of hexagon, anything that interact with the software is called Actor. Two tyes of actors:

- Driver is a main conductor. How starts the interaction, UI, rest endpoint, consumer queue

- Driven. Some parts the recives the interaction, that may be bidirectional (

repository, por example a database) or unidirectional (recipeient, SMTP or queue)

The dependencies are all from the center. Centre depends from nobody, Right side depends from the center, Left side depends from the center too.

Interactions happen through ports. Resuming, a port is an OOP interface.

- Primary port: Used by driver actor, is an API interaction like add items to shopping cart, pay a bill, do bank transfer, etc. Usually, the port correspon to an use case

- Secundary port: used by driven actor, is a SPI interaction like acessing to database, send to queue, etc.

Note: the implementation of primary port interfaces must to be inside the hexagon. The implementation of secundary port interfaces must to be outside the hexagon, because use especifics technologies.

Adapters are pieces of software that allow to external techs interact with ports. They are, essentially, converters.

Thinking about execution flow, it seems that the Centre of Hexagon depends on Right side, but we don't want this. To achieve this goal, we can use IoC.

Resuming ideas from Get your hands dirty on Clean Architecture.

Layers are a solid architecture pattern. If we get them right, we’re able to build domain logic that is independent of the web and persistence layers. But a layered architecture has too many open flanks that allow bad habits to creep in and make the software increasingly harder to change over time

The foundation of a conventional layered architecture is the database. The web layer depends on the domain layer which in turn depends on the persistence layer and thus the database. This is problematic due to several reasons.

- We’re primarily trying to model behavior, and not state. Yes, state is an important part of any application, but the behavior is what changes the state and thus drives the business

- Why are we making the database the foundation of our architecture and not the domain logic? it makes absolutely no sense from a business point of view We should build the domain logic before doing anything else

- If we combine an ORM framework with a layered architecture, we’re easily tempted to mix business rules with persistence aspects. Our services use the persistence model as their business model and not only have to deal with the domain logic, but also with eager vs. lazy loading, database transactions, flushing caches and similar housekeeping tasks. The persistence code is virtually fused into the domain code and thus it’s hard to change one without the other

The only global rule is that from a certain layer, we can only access components in the same layer or a layer below. The layered architecture style itself does not impose those rules on us.

So doing s shortcut once opens the door for doing it a second time. And if someone else was allowed to do it, so am I, right? If there is an option to do something, someone will do it. It is a psychological effect called the “Broken Windows Theory”

The persistence layer will grow fat, because we push components down through the layers. Perfect candidates for this are helper or utility components since they don’t seem to belong to any specific layer. If we want to disable the “shortcut mode” for our architecture, layers are not the best option

we usually spend much more time changing existing code than we do creating new code. This is not only true for those dreaded legacy projects but also for a hot new greenfield project after the initial use cases have been implemented.

A layered architecture does not impose rules on the "size" of the domain Service. A big service has many dependencies to the persistence layer and many components in the web layer depend on it. This makes it hard for us to find the service responsible for the use case we want to work on.

Instead of searching for the user registration use case in the UserService, we would just open up the RegisterUserService and start working.

To be done by a certain date usually implies that we have to work in parallel. You cannot expect a large group of 50 developers to be 5 times as fast as a smaller team of 10 developers in every context. But at a healthy scale, we can certainly expect to be faster with more people on the project. So our architecture must support parallel work.

Working on different use cases will cause the same service to be edited in parallel which leads to merge conflicts and potentially regressions.

If done correctly, and if some additional rules are imposed on it, a layered architecture can be very maintainable and make changing or adding to the codebase a breeze. However, the discussion shows that a layered architecture allows many things to go wrong.

The Single Responsibility Principle: A component should have only one reason to change, so perhaps we should rename the SRP to “Single Reason to Change Principle”.

What does that mean for our architecture? If a component has only one reason to change, we don’t have to worry about this component at all if we change the software for any other reason, because we know that it will still work as expected. Sadly, it’s very easy for a reason to change to propagate through code via the dependencies of a component to other components

In our layered architecture, when the domain layer’s dependency to the persistence layer, each change in the persistence layer potentially requires a change in the domain layer. But the domain code is the most important code in our application. We can turn around (invert) the direction of any dependency within our codebase

Try to invert the dependency between our domain and persistence code so that the persistence code depends on the domain code, reducing the number of reasons to change for the domain code. We create an interface for the repository in the domain layer.

In a clean architecture, the business rules are testable by design and independent of frameworks, databases, UI technologies and other external applications or interfaces.

- The domain code must not have any outward facing dependencies. All dependencies point toward the domain code.

- The core of the architecture contains the domain entities which are accessed by the surrounding use cases. The use cases are what we have called services earlier, but are more fine-grained to have a single responsibility

- Tthe domain code knows nothing about which persistence or UI framework is used. We have all the freedom we can wish for to model the domain code

A Clean Architecture comes at a cost. Since the domain layer is completely decoupled from the outer layers like persistence and UI, we have to maintain a model of our application’s entities in each of the layers. Since the domain layer doesn’t know the persistence layer, we cannot use the same entity classes in the domain layer and have to create them in both layers. That means we have to translate between both representations.

This decoupling is exactly what we wanted to achieve to free the domain code from framework-specific problems.

The application core is represented as a hexagon, giving this architecture style it’s name.

- Within the hexagon, we find our domain entities and the use cases that work with them.

- The hexagon has no outgoing dependencies, all dependencies point towards the center.

- Outside of the hexagon, we find various adapters that interact with the application

- The adapters on the left side are adapters that drive our application (because they call our application core) while the adapters on the right side are driven by our application (because they are called by our application core)

- To allow communication between the application core and the adapters, the application core provides specific ports

- For driving adapters, a port might be an interface that is implemented by one of the use case classes in the core

- For driven adapter, an interface that is implemented by the adapter and called by the core.

In a hexagonal architecture we have entities, use cases, incoming and outgoing ports and incoming and outgoing (or “driving” and “driven”) adapters as our main architecture elements.

- On the highest level, we again have a package named by the boundary, indicating that this is the module implementing the use cases around this boundary.

- The domain package containing our domain model

- The application package contains a service layer around this domain model

- The adapter package contains the incoming adapters

In most software development projects the architecture is only an abstract concept that cannot be directly mapped to the code, but this expressive package structure promotes active thinking about the architecture. There is no perfection. But with an expressive package structure, we can at least reduce the the gap between code and architecture.

Usually, a use case follows these steps:

- Take input

- Validate business rules

- Manipulate model state

- Return output

The first step is not "Validate input" because use case code should care about the domain logic and we shouldn’t pollute it with input validation.

We’ll create a separate service class for each use case instead of putting all use cases into a single service class.

It’s not a responsibility of a use case class, but it belongs into the application layer. Do we want to trust the caller to have validated everything as is needed for the use case?

We can put these validations on the creation input object. If any of these conditions is violated, we simply refuse object creation by throwing an exception during construction. Since the objects are part of the use cases’ API, they are located in the incoming port package. The validation remains in the core of the application.

With validation located in the input model we have effectively created an anti-corruption layer around our use case implementations.

A dedicated input model for each use case makes the use case much clearer and also decouples it from other use cases, preventing unwanted side effects. It comes with a cost, however, because we have to map incoming data into different input models for different use cases.

Business rules are the core of the application and should be handled with appropriate care. A main different with validation input is that validating a business rule requires access to the current state of the domain model while validating input does not, a business rule needs more context.

A frequent discussion is whether to implement a rich domain model following the DDD philosophy or an “anemic” domain model.

- In a rich domain model, as much of the domain logic as possible is implemented within the entities at the core of the application. The entities provide methods to change state and only allow changes that are valid according to the business rules.

- In an “anemic” domain model, the entities themselves are very thin. They usually only provide fields to hold the state and getter and setter methods to read and change it. They don’t contain any domain logic.

Both styles can be implemented using this architecture

It has benefits if the output is as specific to the use case as possible. The output should only include the data that is really needed for the caller to work. We should ask them to try to keep our use cases as specific as possible. When in doubt, return as little as possible.

For the same reason we might want to resist the temptation to use our domain entities as output model. We don’t want our domain entities to change for more reasons than necessary

Do we create a specific use case implementation for this?

- If this is considered a use case in the context of the project, by all means we should implement it just like the other ones.

- From the viewpoint of the application core, however, this is a simple query for data. So if it’s not considered a use case in the context of the project, we can implement it as a query to set it apart from the real use cases.

This way, read-only queries are clearly distinguishable from modifying use cases (or “commands”) in our codebase. This plays nicely with concepts like Command-Query Separation (CQS) and Command-Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS).

For Dependency Inversion, the control flow goes from the controllers in the web adapter to the services in the application layer.

We could just as well let the web adapter call the use cases directly, but having ports in place, we know exactly which communication with the outside world takes place, which is a valuable information for any maintenance engineer working on your legacy codebase.

-

How does the application core send this real-time data to the web adapter which in turns sends it to the user’s browser?

For this scenario, we definitely need a port. This port must be implemented by the web adapter and called by the application core, make the web adapter an incoming and outgoing adapter.

-

The state of the incoming objects can then be validated

We’re talking about the input model to the web adapter. I don’t advocate to implement the same validations in the web adapter as we have already done in the input model of the use cases. Instead, we should validate that we can transform the input model of the web adapter into the input model of the use cases.

If anything goes wrong on the way and an exception is thrown, the web adapter must translate the error into a message that is sent back to the caller. Boundary between web adapter and application layer comes naturally if we start development with the domain and application layers instead of with the web layer.

How many controllers do we build? Must to be as little as possible!

A popular approach is to create a single domain Controller that accepts requests for all operations that relate this domain. Everything concerning it resource is in a single class. But I guess less code per class is a good thing.

Putting all operations into a single controller class encourages re-use of data structures and it serves as a bucket for everything that is needed in any of the operations

I advocate the approach to create a separate controller, potentially in a separate package, for each operation. Also, we should name the methods and classes as close to our use cases as possible.

Each controller can have its own model, or use primitives as input. The model classes may even be private to the controller’s package so they may not accidentally be re-used somewhere else.

There are certainly cases where the usual suspects Create..., Update..., and Delete... sufficiently describe a use case, but we might want to think twice before actually using them.

When slicing web controllers, we should not be afraid to build many small classes that don’t share a model.

Persistence adapter that provides persistence functionality to the application services. Our application services call port interfaces to access persistence functionality, that are implemented by a persistence adapter. It is responsible for talking to the database.

Naturally, at runtime we still have a dependency from our application core to the persistence adapter. If we modify code in the persistence layer and introduce a bug, for example, we may still break functionality in the application core.

- Take input

- Map input into database format

- Send input to the database

- Map database output into application format

- Return output

The input model to the persistence adapter lies within the application core and not within the persistence adapter itself. The port interface is how to slice the port interfaces that define the database operations.

The Interface Segregation Principle provides an answer to this problem. It states that broad interfaces should be split into specific ones so that clients only know the methods they need.

Each service now only depends on the methods it actually needs. What’s more, the names of the ports clearly state what they’re about. In a test, we no longer have to think about which methods to mock

Of course, the “one method per port” approach may not be applicable in all circumstances.

A single persistence adapter class that implements all persistence ports. There is no rule, however, that forbids us to create more than one class, as long as all persistence ports are implemented.

-

Where do we put our transaction boundaries?

Since the persistence adapter doesn’t know which other database operations are part of the same use case, it cannot decide when to open and close a transaction.

If we want our services to stay pure and not be stained with @Transactional annotations, we may use aspect-oriented programming (for example with AspectJ) in order to weave transaction boundaries into our codebase.

On the most of projects, no one can answer targeted questions about the team’s testing strategy.

When tests are done during development of a feature and not after, they become a development tool and no longer feel like a chore.

The basic statement is that we should have high coverage of fine-grained tests that are cheap to build, easy to maintain, fast-running, and stable. A unit test usually instantiates a single class and tests its functionality through its interface mocks, simulating the behavior of the real classes as it’s needed during the test.

The test is vulnerable to changes in the structure of the code under test and not only its behavior.

Since the web controller is heavily bound to the Spring framework, it makes sense to test it integrated into this framework instead of testing it in isolation.

Line coverage is a bad metric to measure test success.

Pro-Mapping Developer: > If we don’t map between layers, we have to use the same model in both layers which means that the layers will be tightly coupled!Contra-Mapping Developer: > But if we do map between layers, we produce a lot of boilerplate code which is overkill for many use cases, since they’re only doing CRUD and have the same model across layers anyways!

There’s truth to both sides of the argument!

The web and persistence layers may have special requirements to their models. the model classes might need some annotations that define how to serialize certain fields into JSON

The persistence layer if we’re using an ORM framework, which might require some annotations that define the database mapping

Even though it might feel dirty, a “no mapping” strategy can be perfectly valid. Consider a simple CRUD use case. Do we really need to map the same fields from the web model into the domain model and from the domain model into the persistence model? I’d say we don’t.

Persistence and Web layer has its own model, which may have a structure that is completely different from the domain model.

The mapping responsibilities are clear: the outer layers / adapters map into the model of the inner layers and back.

It has drawbacks:

- It usually ends up in a lot of boilerplate code

- Implementing the mapping between models usually takes up a good portion of our time.

- The domain model is used to communicate across layer boundaries. The incoming ports and outgoing ports use domain objects as input parameters and return values.

Just like the “No Mapping” strategy, the “Two-Way” mapping strategy is not a silver bullet.

This mapping strategy introduces a separate input and output model per operation

-

Instead of using the domain model to communicate across layer boundaries, we use a model specific to each operation. Such a command makes the interface to the application layer very explicit, with little room for interpretation.

-

The application layer is then responsible for mapping the command object into whatever it needs to modify the domain model according to the use case.

-

Mapping from the one layer into many different commands requires even more mapping code than mapping between a single web model and domain model.

-

The mapping strategies can and should be mixed. No single mapping strategy needs to be a global rule across all layers.

The models in all layers implement the same interface that encapsulates the state of the domain model by providing getter methods on the relevant attributes.

-

If we want to pass a domain object to the outer layers, we can do so without mapping, since the domain object implements the state interface expected by the incoming and outgoing ports.

-

They cannot inadvertently modify the state of the domain object since the modifying behavior is not exposed by the state interface.

It depends! We should resist the urge to define a single strategy as a hard-and-fast global rule

the strategy that was the best for the job yesterday might not still be the best for the job today.

In order to decide which strategy to use, agree upon a set of guidelines and should answer the question which mapping strategy should be the first choice in which situation.

We might for example define different mapping guidelines to modifying use cases than we do to queries different mapping strategies between the web and application layer and between the application and persistence layer.

This selection of mapping strategies per situation certainly is harder and requires more communication than simply using the same mapping strategy for all situations

The effect of sharing are coupled to each other. If we change something within the shared both use cases are affected. They share a reason to change in terms of the Single Responsibility Principle.

Sharing input and output models between use cases is valid if the use cases are functionally bound, because we actually want both use cases to be affected if we change a certain detail. If both use cases should be able to evolve separately from each other we should separate the use cases from the start

If we have a domain entity and an incoming port, we might be tempted to use the entity as the input and/or output model of the incoming port. The incoming port has a dependency to the domain entity. The consequence of this is that we’ve added another reason for the Account entity to change.

For simple create or update use cases, a domain entity in the use case interface may be fine, since the entity contains exactly the information we need to persist its state in the database.

What makes this shortcut dangerous is the fact that many use cases start their lives as a simple create or update use case only to become beasts of complex domain logic over time

While the outgoing ports are necessary to invert the dependency between the application and the outgoing adapters, we don’t need the incoming ports for dependency inversion. We could decide to let the incoming adapters access our application services directly.

By removing the incoming ports, we have reduced a layer of abstraction between incoming adapters and the application layer. Once we remove them, we must know more about the internals of our application to find out which service method we can call to implement a certain use case. This makes every entry point into the application layer a very conscious decision.

For certain use cases we might want to skip the application layer as a whole an outgoing adapter directly implements an incoming port and replaces the application service. It is very tempting to do this for simple CRUD use cases, since in this case an application service usually only forwards a create, update or delete request to the persistence adapter. This, however, requires a shared model between the incoming adapter and the outgoing adapter

There are times when shortcuts make sense from an economic point of view. It’s tempting to introduce shortcuts for simple CRUD use cases, since for them, implementing the whole architecture feels like overkill (and the shortcuts don’t feel like shortcuts)

When should we actually use the hexagonal architecture style?

- Evolving domain code free from external influence is the single most important argument for the hexagonal architecture style.

- This is why this architecture style is such a good match for DDD practices.

- If the domain code is not the most important thing in your application, you probably don’t need this architecture style.

It depends on the type of software to be built. It depends on the role of the domain code. It depends on the experience of the team.