Category theory is a branch of mathematics originally developed to transport ideas from one branch of mathematics to another, e.g. from topology to algebra. Applied category theory refers to efforts to transport the ideas of category theory from mathematics to other disciplines in science, engineering, and industry.

- Dynamical systems and networks

- Systems biology

- Cognition and AI

- Causality

- Generative Effects

- Posets

- Monotone functions

- Galois Connections

- Meets and joins

-

Going to discuss generative effects within the context of posets (preorder sets) which have some really interesting properties

-

I'm going to do that by showing some motivating examples and introduce you to different concepts that are central to category theory.

-

First we need something categories to play with so let's start with an interesting one called the category of posets.

-

Whenever you have a set of things and a reasonable way deciding when anything in that set is "bigger" than some other thing, or "more expensive", or "taller", or "heavier", or "better" in any well-defined sense, or... anything like that, you've got a poset.

-

In Haskell we might define this using a typeclass:

class Eq a => PartialOrd a where

lessThanOrEq :: a -> a -> Bool

=< :: a -> a -> BoolWhen y is bigger than x we write x =< y. x lte y.

Reflexivity :: x =< x

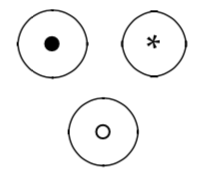

Transitivity :: a =< b && b =< c implies a =< cLet's explore a couple of functions on sets. Here we have an unconnected set of three points. We'll call them the dot, circle, and star. The system I'll describe will be a way of connecting these dots together. We might think of these points as sites on a power grid, computers on a network, or people susceptible to some disease.

Connections in this system are symmetric, which is to say if a is connected to b, then b is connected to a. They're also transitive just like the partial order law we described above. If a is connected to b and b is connected to c then a is connected to c. We can contrast this system with a system like friendship. The friend of my friend is not necessarily my friend.

Say we had a function or an observation about this system which had the type of:

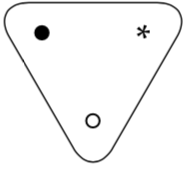

isDotConnectedToStar :: PointSet -> BoolFor the following set it would be false.

And for the following set it would be true.

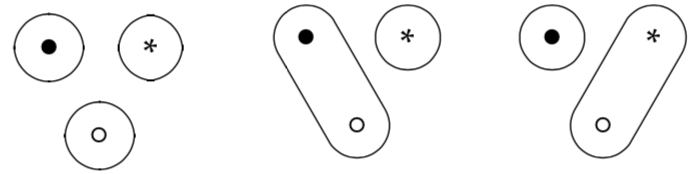

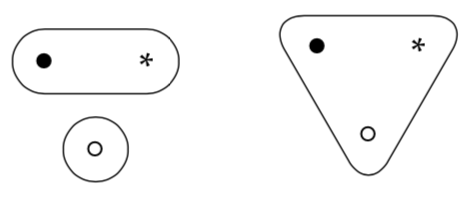

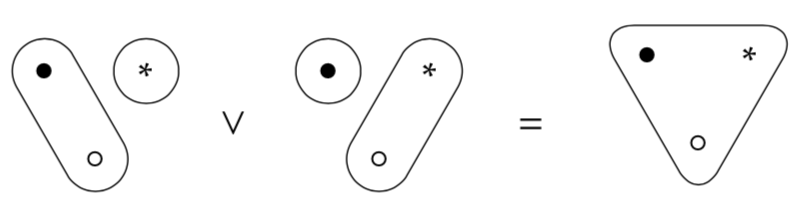

Now let's define another operation on this type of system we'll call join. The join of two systems is given by combining their connections. We denote this with ⌄ that kind of looks like a union operation but it does a little more. The high-level way to say this is "to take the transitive closure of the union of the connections in A and B."

- So this is fine in the above case, but below we see that the

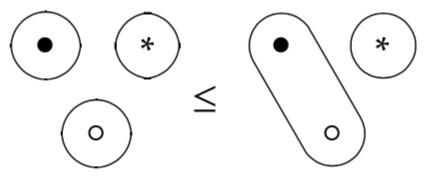

isDotConnectedToStarwould be false for both point sets, but true for the join f the point sets. The join operation has led to what is called a generative effect, or an operation that does not preserve the observations of the systems. While this is a pretty simple example, knowing whether a function leads to generative effects is incredibly important within the context of any category, data structure and its operations.

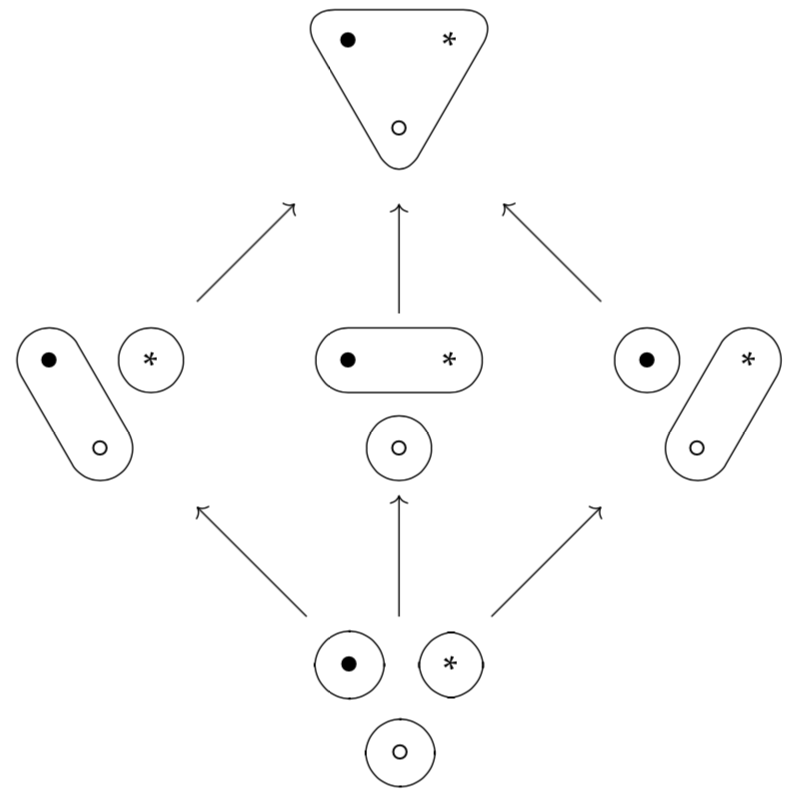

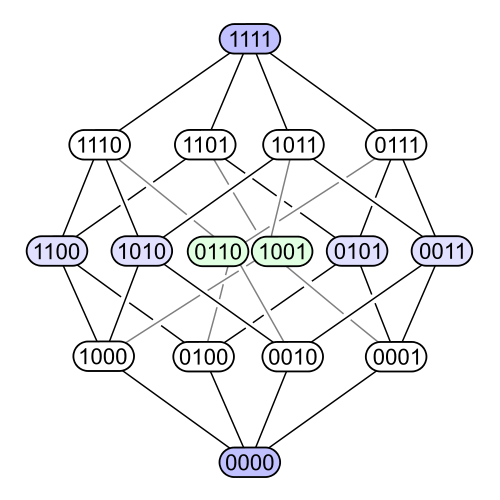

Category theory is all about organizing and layering structures. If we think about the sets we've talked about and the lessThanOrEq relation we can see that our isDotConnectedToStar function preserves the order between our sets. Let's say we define lessThanOrEq by saying that sets with smaller connections are smaller than sets with larger connections.

If we take a look at the whole set, we can see that running the whole thing through isDotConnectedToStar preserves the order. The bottom set would be false, the left and right set would be false, the middle and top set would be true.

As we've already seen, the isDotConnectedToStar does not preserve through join operations so we need an additional inequality to describe that behavior:

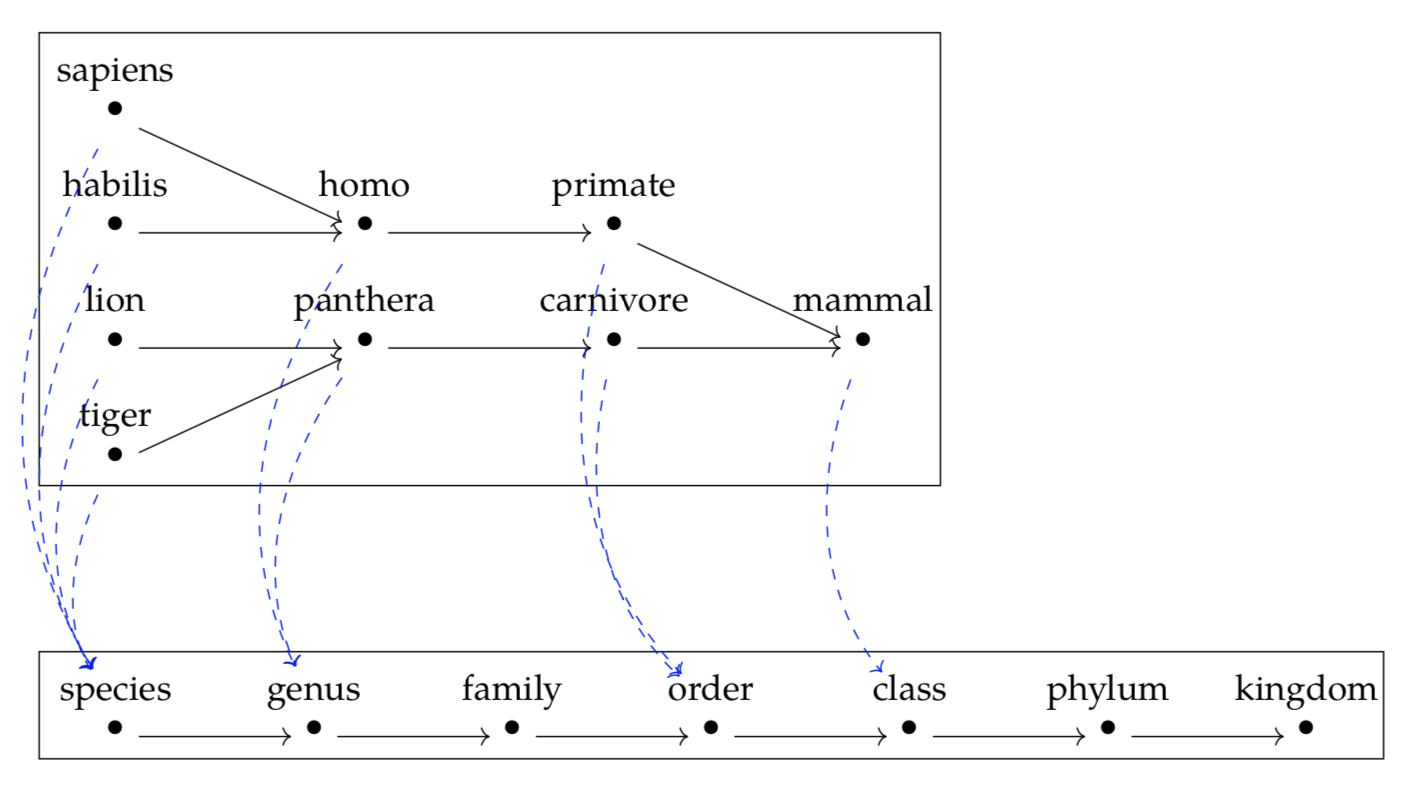

(isDotConnectedToStar a `join` isDotConnectedToStar b) `lessThanOrEq` isDotConnectedToStar (a `join` b)We've been talking about the properties preserved through certain functions we've defined. In the above case, that the isDotConnectedToStar function preserves order, but not joins. If we jump up a level, and talk about how posets themselves can be related we can talk about monotone maps. Monotone maps are functions that preserve poset orders. Let's take a look at some examples.

As we said earlier, posets are sets with a simple order functions between elements. We can use this structure to define two types of elements with special properties. In the generative effect example we talked about joins and now we'll also talk about meets.

The meets of some poset P would be the greatest lower bound elements of P. The joins of some poset P would be the lowest upper bounds of P. They are also referred to the infima and the suprema, respectively.

Adam Elie wrote his PhD Thesis in 2017 on Systems, Generativity and Interactional Effects where he thinks of monotone functions as observations. A monotone function of type P -> Q is a phenomenon of P as observed by Q. He defines generative effects of such a function to be its failure to preserve joins.

We say that a monotone function m :: P -> Q preserves meets if m(a meet b) = m(a) meet m(b). We say that a monotone function preserves joins if m(a join b) = m(a) join m(b).

We say that a monotone function m :: P -> Q sustains generative effects if there exist elements a :: P, q :: P such that

m(a) `join` m(b) != m(a `join` b)If what Adam proposes is true, the process of combining large systems or reasoning about their subsystems depends on our ability to preserve the joins or meets of that system, respectively.

So now we've gotten to the cool part which are Galois connections. Galois connections are a fancy name for a pair of functions that tell you the best possible way to recover data that can't be recovered. More precisely, they tell you the best approximation to reversing a computation that can't be reversed.

Say someone hands you the output of some computation, and asks you what the input was. Sometimes there's a unique right answer. But sometimes there's more than one answer, or no answer! So here things might seem impossible but we can't let that stop us.

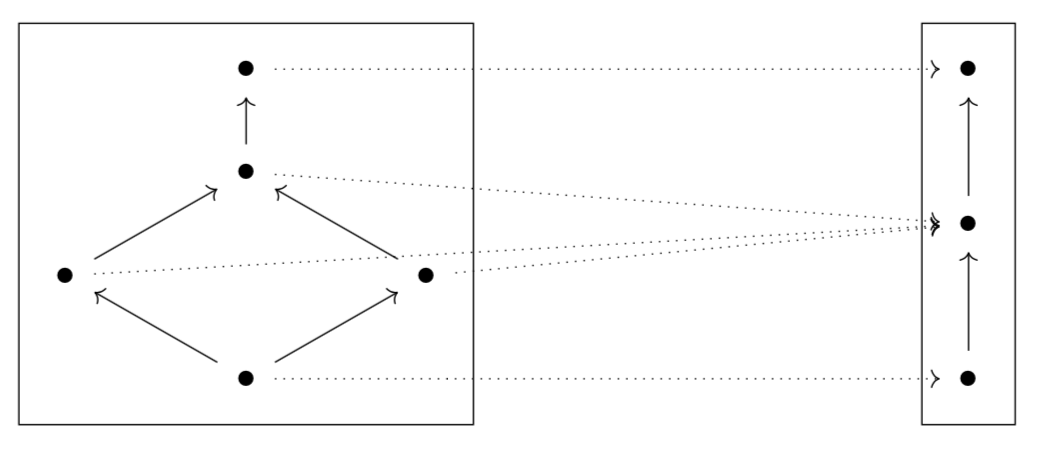

Ok so let's define what one is. A Galois connection between two posets P and Q is a pair of monotone functions f :: P -> Q and g :: Q -> P such that f(p) =< q iff p =< g(q). We say that f is the left adjoint and g is the right adjoint.

Let's break down what this means. Say a function that doubles every natural number:

f :: Integer -> Integer

f a = 2 * aSo if I say 2a = 4 tell me a you'd say 2. But if I say 2a = 3 tell me a you can't do it because there's no inverse here. 2 / a isn't defined for 3. But let's find an approximation anyway and this function g paired with f will end up being a galois connection.

- f(a) =< b iff p =< g(b)

- 2a =< b iff a =< g(b)

- 2a =< b iff a =< b / 2

- 2a =< b iff a =< floor(b / 2)

- 2a =< b iff a =< ceiling(b / 2)

So here we have two definitions for g, one from below and one from above. 2a = 3 would result in 1 if we use floor(b / 2), or 2 if we use the more liberal definition of ceil(b / 2). In this case, the left adjoint is the approximation "from below". It comes as close as possible to the (perhaps nonexistent) correct answer while making sure to never choose a number that is too small. The right adjoint comes as close as possible to making sure a number is not too big.

-- a function that takes a set of balls and places them in a set of buckets

f :: Set Ball -> Set Bucket

f [1, 2, 3] = Set (First 1 2 2) (Second 1) (Third 1 1 2 3)

-- A function that takes a set of buckets and tells you which balls are in them

-- This might be called a pullback along f.

f* :: Set Bucket -> Set Ball

f* Set (First 3 2) (Second 1) = 3 2 1

-- This map hence takes a set of balls, and tells you all the buckets that contain at least one of these balls.

-- The actual definition of leftAdjointF can be derived from the definitions of f and f*.

leftAdjointF :: Set Ball -> Set Bucket

leftAdjointF [2, 3] = Set (Second 1) (Third 1 1 2 3)

-- This map takes a set of balls, and tells you all the buckets that only contain balls from the set.

-- The actual definition of rightAdjointF can be derived from the definitions of f and f*.

rightAdjointF :: Set Ball -> Set Bucket

rightAdjointF [1] = Set (Second 1)If some function f :: A -> B has a left or right adjoint and A is a poset, those adjoints are unique. So it's always a good idea to try to find them!

Right adjoints preserve meets. Similarly, left adjoints preserve joins.

- Posets are a special case of categories,

- Monotone functions between posets are a special case of functors between categories,

- Galois connections between posets are a special case of adjoint functors between categories,

- Left adjoint monotone functions are a special case of left adjoint functors,

- Right adjoint monotone functions are a special case of right adjoint functors,

- Meets are a special case of limits, and

- Joins are a special case of colimits.

Seven Sketches in Applied Category Theory