Forked from Froussios/Intro-To-RxJava, combine all pages into one for easy look-up.

Users expect real time data. They want their tweets now. Their order confirmed now. They need prices accurate as of now. Their online games need to be responsive. As a developer, you demand fire-and-forget messaging. You don't want to be blocked waiting for a result. You want to have the result pushed to you when it is ready. Even better, when working with result sets, you want to receive individual results as they are ready. You do not want to wait for the entire set to be processed before you see the first row. The world has moved to push; users are waiting for us to catch up. Developers have tools to push data, this is easy. Developers need tools to react to push data

Welcome to Rx. This book is based on Rx.NET's www.introtorx.com and it introduces beginners to RxJava, the Netflix implementation of the original Microsoft library. Rx is a powerful tool that enables the solution of problems in an elegant declarative style, familiar to functional programmers. Rx has several benefits:

- Unitive

- Queries in Rx are done in the same style as other libraries inspired by functional programming, such as Java streams. In Rx, one can use functional style transformations on event streams.

- Extensible

- RxJava can be extended with custom operators. Although Java does not allow for this to happen in an elegant way, RxJava offers all the extensibility one can find Rx implementations in other languages.

- Declarative

- Functional transformations are read in a declarative way.

- Composable

- Rx operators can be combined to produce more complicated operations.

- Transformative

- Rx operators can transform one type of data to another, reducing, mapping or expanding streams as needed.

Rx is fit for composing and consuming sequences of events. We present some of the use cases for Rx, according to www.introtorx.com

- UI events like mouse move, button click

- Domain events like property changed, collection updated, "Order Filled", "Registration accepted" etc.

- Infrastructure events like from file watcher, system and WMI events

- Integration events like a broadcast from a message bus or a push event from WebSockets API or other low latency middleware like Nirvana

- Integration with a CEP engine like StreamInsight or StreamBase.

- Result of

Futureor equivalent pattern

Those patterns are already well adopted and you may find that introducing Rx on top of that does not add to the development process.

- Translating iterables to observables, just for the sake of working on them through an Rx library.

Rx is based around two fundamental types, while several others expand the functionality around the core types. Those two core types are the Observable and the Observer, which will be introduced in this chapter. We will also introduce Subjects, which ease the learning curve.

Rx builds upon the Observer pattern. It is not unique in doing so. Event handling already exists in Java (e.g. JavaFX's EventHandler). Those are simpler approaches, which suffer in comparison to Rx:

- Events through event handlers are hard to compose.

- They cannot be queried over time

- They can lead to memory leaks

- These is no standard way of signaling completion.

- Require manual handling of concurrency and multithreading.

Observable is the first core element that we will see. This class contains a lot of the implementation of Rx, including all of the core operators. We will be examining it step by step throughout this book. For now, we must understand the Subscribe method. Here is one key overload of the method:

public final Subscription subscribe(Subscriber<? super T> subscriber)This is the method that you use to receive the values emitted by the observable. As the values come to be pushed (through policies that we will discuss throughout this book), they are pushed to the subscriber, which is then responsible for the behaviour intended by the consumer. The Subscriber here is an implementation of the Observer interface.

An observable pushes 3 kinds of events

- Values

- Completion, which indicates that no more values will be pushed.

- Errors, if something caused the sequence to fail. These events also imply termination.

We already saw one abstract implementation of the Observer, Subscriber. Subscriber implements some extra functionality and should be used as the basis for our implementations of Observer. For now, it is simpler to first understand the interface.

interface Observer<T> {

void onCompleted();

void onError(java.lang.Throwable e);

void onNext(T t);

}Those three methods are the behaviour that is executed every time the observable pushes a value. The observer will have its onNext called zero or more times, optionally followed by an onCompleted or an onError. No calls happen after a call to onError or onCompleted.

When developing Rx code, you'll see a lot of Observable, but not so much of Observer. While it is important to understand the Observer, there are shorthands that remove the need to instantiate it yourself.

You could manually implement Observer or extend Observable. In reality that will usually be unnecessary, since Rx already provides all the building blocks you need. It is also dangerous, as interaction between parts of Rx includes conventions and internal plumming that are not obvious to a beginner. It is both simpler and safer to use the many tools that Rx gives you for generating the functionality that you need.

To subscribe to an observable, it is not necessary to provide instances of Observer at all. There are overloads to subscribe that simply take the functions to be executed for onNext, onError and onSubscribe, hiding away the instantiation of the corresponding Observer. It is not even necessary to provide each of those functions. You can provide a subset of them, i.e. just onNext or just onNext and onError.

The introduction of lambda functions in Java 1.8 makes these overloads very convenient for the short examples that exist in this book.

Subjects are an extension of the Observable that also implements the Observer interface. The idea may sound odd at first, but they make things a lot simpler in some cases. They can have events pushed to them (like observers), which they then push further to their own subscribers (like observables). This makes them ideal entry points into Rx code: when you have values coming in from outside of Rx, you can push them into a Subject, turning them into an observable. You can think of them as entry points to an Rx pipeline.

Subject has two parameter types: the input type and the output type. This was designed so for the sake of abstraction and not because the common uses for subjects involve transforming values. There are transformation operators to do that, which we will see later.

There are a few different implementations of Subject. We will now examine the most important ones and their differences.

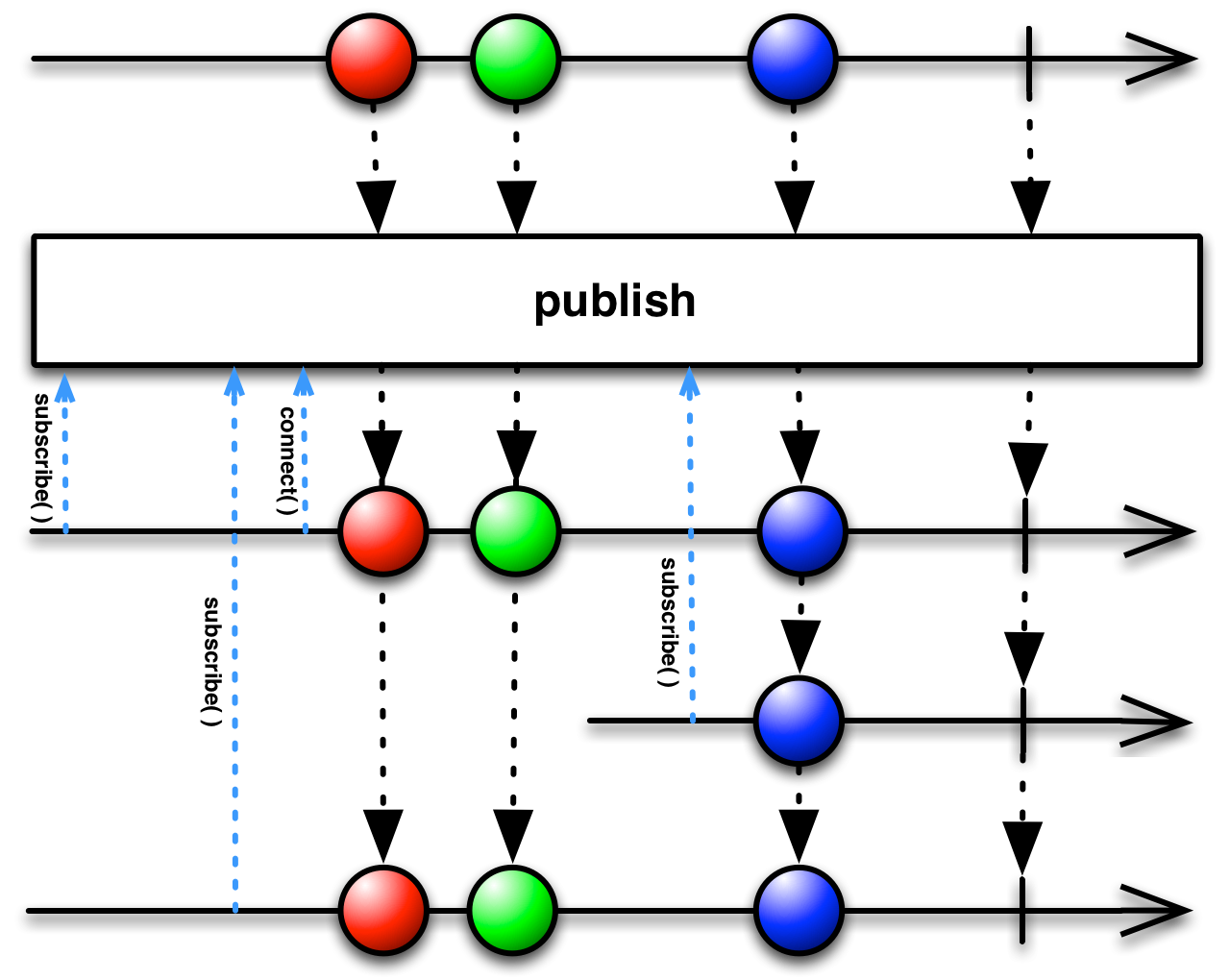

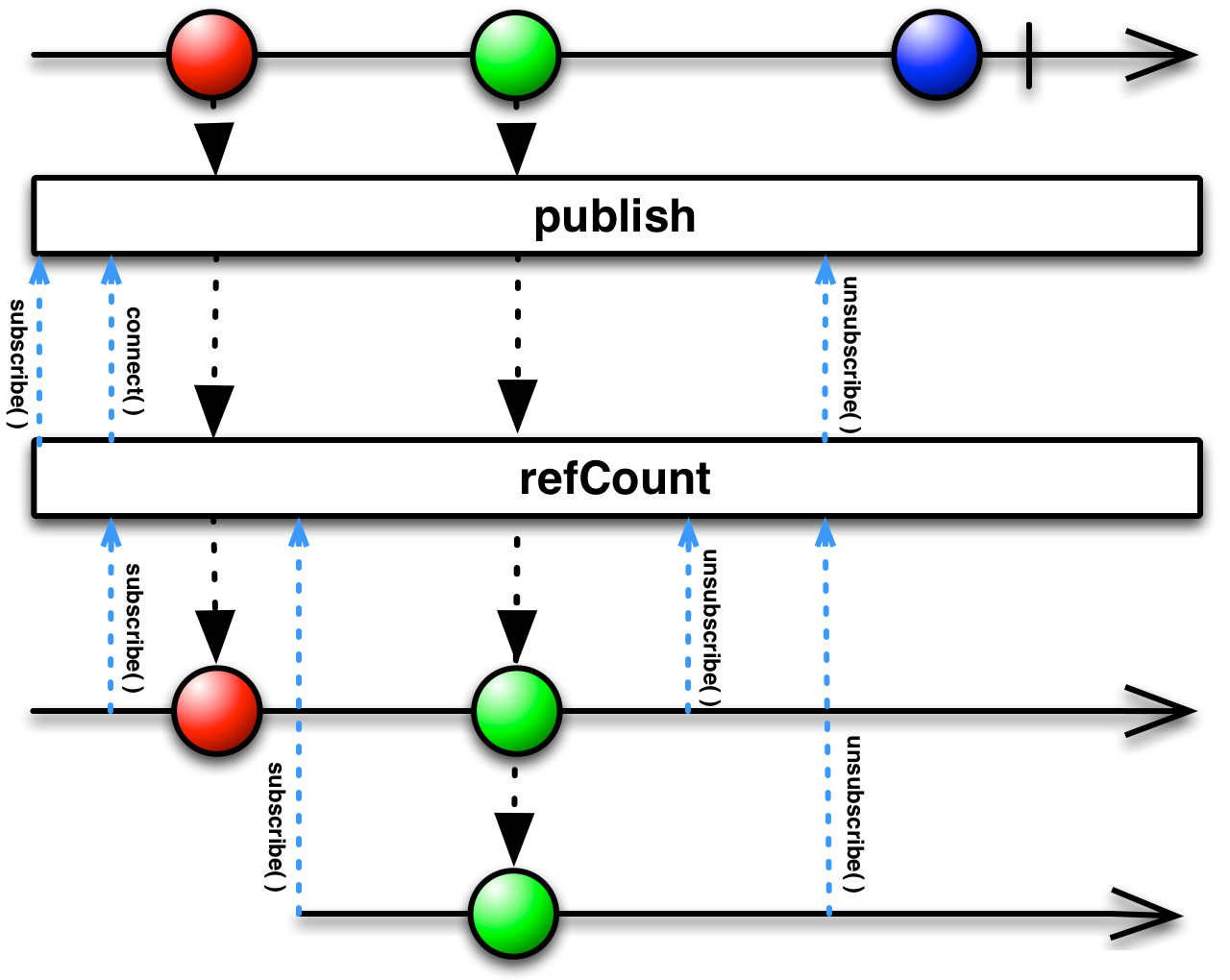

PublishSubject is the most straight-forward kind of subject. When a value is pushed into a PublishSubject, the subject pushes it to every subscriber that is subscribed to it at that moment.

public static void main(String[] args) {

PublishSubject<Integer> subject = PublishSubject.create();

subject.onNext(1);

subject.subscribe(System.out::println);

subject.onNext(2);

subject.onNext(3);

subject.onNext(4);

}2

3

4

As we can see in the example, 1 isn't printed because we weren't subscribed when it was pushed. After we subscribed, we began receiving the values that were pushed to the subject.

This is the first time we see subscribe being used, so it is worth paying attention to how it was used. In this case, we used the overload which expects one Function for the case of onNext. That function takes an argument of type Integer and returns nothing. Functions without a return type are also called actions. We can provide that function in different ways:

- we can supply an instance of

Action1<Integer>, - implicitly create one using a lambda expression or

- pass a reference to an existing method that fits the signature.

In this case,

System.out::printlnhas an overload that acceptsObject, so we passed a reference to it.subscribewill callprintlnwith the arriving values as the argument.

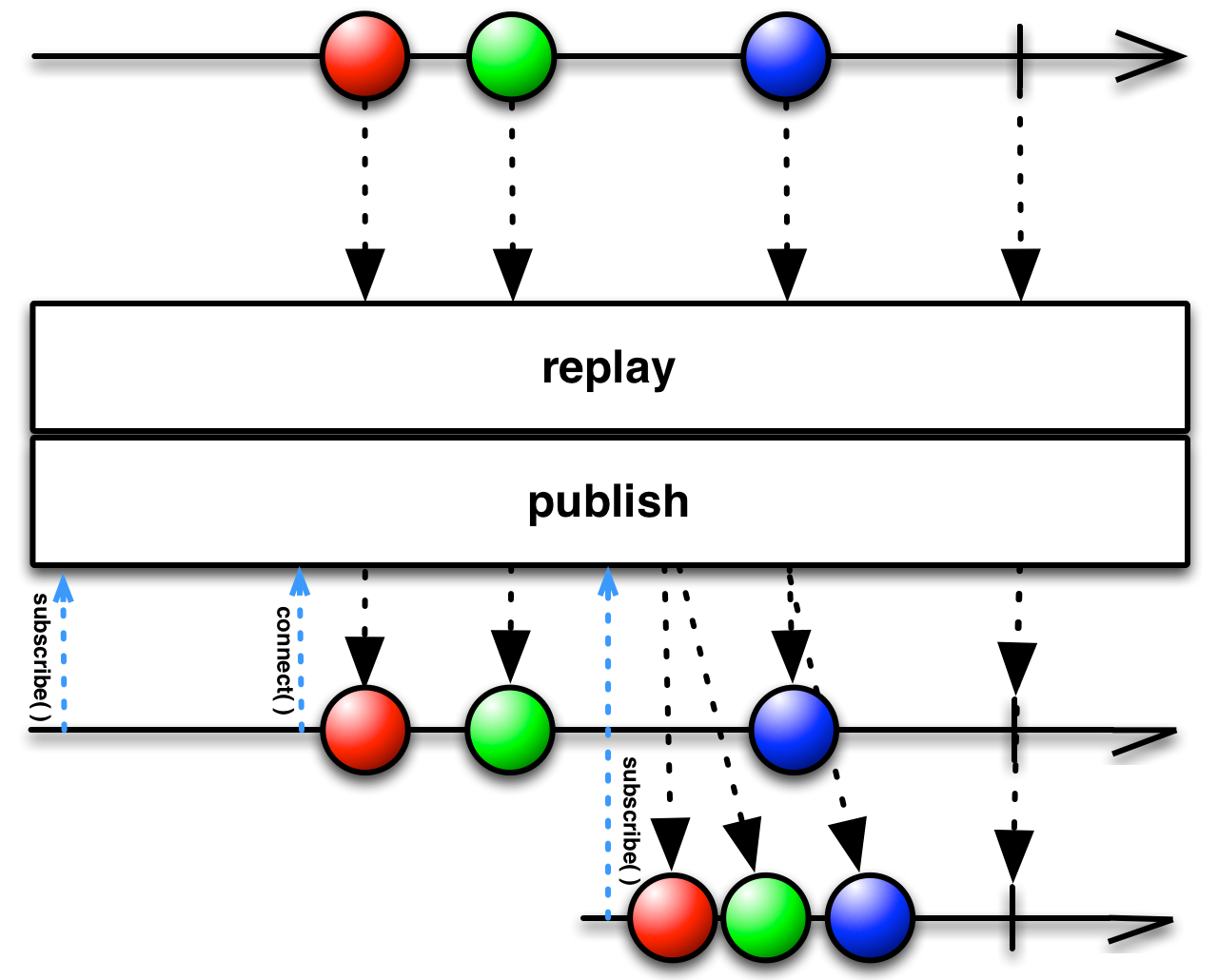

ReplaySubject has the special feature of caching all the values pushed to it. When a new subscription is made, the event sequence is replayed from the start for the new subscriber. After catching up, every subscriber receives new events as they come.

ReplaySubject<Integer> s = ReplaySubject.create();

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println("Early:" + v));

s.onNext(0);

s.onNext(1);

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println("Late: " + v));

s.onNext(2);Early:0

Early:1

Late: 0

Late: 1

Early:2

Late: 2

All the values are received by the subscribers, even though one was late. Also notice that the late subscriber had everything replayed to it before proceeding to the next value.

Caching everything isn't always a good idea, as an observable sequence can run for a long time. There are ways to limit the size of the internal buffer. ReplaySubject.createWithSize limits the size of the buffer, while ReplaySubject.createWithTime limits how long an object can stay cached.

ReplaySubject<Integer> s = ReplaySubject.createWithSize(2);

s.onNext(0);

s.onNext(1);

s.onNext(2);

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println("Late: " + v));

s.onNext(3);Late: 1

Late: 2

Late: 3

Our late subscriber now missed the first value, which fell off the buffer of size 2. Similarily, old values fall off the buffer as time passes, when the subject is created with createWithTime

ReplaySubject<Integer> s = ReplaySubject.createWithTime(150, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS,

Schedulers.immediate());

s.onNext(0);

Thread.sleep(100);

s.onNext(1);

Thread.sleep(100);

s.onNext(2);

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println("Late: " + v));

s.onNext(3);Late: 1

Late: 2

Late: 3

Creating a ReplaySubject with time requires a Scheduler, which is Rx's way of keeping time. Feel free to ignore this for now, as we will properly introduce schedulers in the chapter about concurrency.

ReplaySubject.createWithTimeAndSize limits both, which ever comes first.

BehaviorSubject only remembers the last value. It is similar to a ReplaySubject with a buffer of size 1. An initial value can be provided on creation, therefore guaranteeing that a value always will be available immediately on subscription.

BehaviorSubject<Integer> s = BehaviorSubject.create();

s.onNext(0);

s.onNext(1);

s.onNext(2);

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println("Late: " + v));

s.onNext(3);Late: 2

Late: 3

The following example just completes, since that is the last event.

BehaviorSubject<Integer> s = BehaviorSubject.create();

s.onNext(0);

s.onNext(1);

s.onNext(2);

s.onCompleted();

s.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Late: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error"),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);An initial value is provided to be available if anyone subscribes before the first value is pushed.

BehaviorSubject<Integer> s = BehaviorSubject.create(0);

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));

s.onNext(1);0

1

Since the defining role of a BehaviorSubject is to always have a value readily available, it is unusual to create one without an initial value. It is also unusual to terminate one.

AsyncSubject also caches the last value. The difference now is that it doesn't emit anything until the sequence completes. Its use is to emit a single value and immediately complete.

AsyncSubject<Integer> s = AsyncSubject.create();

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));

s.onNext(0);

s.onNext(1);

s.onNext(2);

s.onCompleted();2

Note that, if we didn't do s.onCompleted();, this example would have printed nothing.

As we already mentioned, there are contracts in Rx that are not obvious in the code. An important one is that no events are emitted after a termination event (onError or onCompleted). The implemented subjects respect that, and the subscribe method also prevents some violations of the contract.

Subject<Integer, Integer> s = ReplaySubject.create();

s.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));

s.onNext(0);

s.onCompleted();

s.onNext(1);

s.onNext(2);0

Safety nets like these are not guaranteed in the entirety of the implementation of Rx. It is best that you are mindful not to violate the contract, as this may lead to undefined behaviour.

The idea behind Rx is that it is unknown when a sequence emits values or terminates, but you still have control over when you begin and stop accepting values. Subscriptions may be linked to allocated resources that you will want to release at the end of a sequence. Rx provides control over your subscriptions to enable you to do that.

There are several overloads to Observable.subscribe, which are shorthands for the same thing.

Subscription subscribe()

Subscription subscribe(Action1<? super T> onNext)

Subscription subscribe(Action1<? super T> onNext, Action1<java.lang.Throwable> onError)

Subscription subscribe(Action1<? super T> onNext, Action1<java.lang.Throwable> onError, Action0 onComplete)

Subscription subscribe(Observer<? super T> observer)

Subscription subscribe(Subscriber<? super T> subscriber)subscribe() consumes events but performs no actions. The overloads that take one or more Action will construct a Subscriber with the functions that you provide. Where you don't give an action, the event is practically ignored.

In the following example, we handle the error of a sequence that failed.

Subject<Integer, Integer> s = ReplaySubject.create();

s.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.err.println(e));

s.onNext(0);

s.onError(new Exception("Oops"));Output

0

java.lang.Exception: Oops

If we do not provide a function for error handling, an OnErrorNotImplementedException will be thrown at the point where s.onError is called, which is the producer's side. It happens here that the producer and the consumer are side-by-side, so we could do a traditional try-catch. However, on a compartmentalised system, the producer and the subscriber very often are in different places. Unless the consumer provides a handle for errors to subscribe, they will never know that an error has occured and that the sequence was terminated.

You can also stop receiving values before a sequence terminates. Every subscribe overload returns an instance of Subscription, which is an interface with 2 methods:

boolean isUnsubscribed()

void unsubscribe()Calling unsubscribe will stop events from being pushed to your observer.

Subject<Integer, Integer> values = ReplaySubject.create();

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.err.println(e),

() -> System.out.println("Done")

);

values.onNext(0);

values.onNext(1);

subscription.unsubscribe();

values.onNext(2);0

1

Unsubscribing one observer does not interfere with other observers on the same observable.

Subject<Integer, Integer> values = ReplaySubject.create();

Subscription subscription1 = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("First: " + v)

);

Subscription subscription2 = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Second: " + v)

);

values.onNext(0);

values.onNext(1);

subscription1.unsubscribe();

System.out.println("Unsubscribed first");

values.onNext(2);First: 0

Second: 0

First: 1

Second: 1

Unsubscribed first

Second: 2

onError and onCompleted mean the termination of a sequence. An observable that complies with the Rx contract will not emit anything after either of those events. This is something to note both when consuming in Rx and when implementing your own observables.

Subject<Integer, Integer> values = ReplaySubject.create();

Subscription subscription1 = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("First: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("First: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);

values.onNext(0);

values.onNext(1);

values.onCompleted();

values.onNext(2);First: 0

First: 1

Completed

A Subscription is tied to the resources it uses. For that reason, you should remember to dispose of subscriptions. You can create the binding between a Subscription and the necessary resources using the Subscriptions factory.

Subscription s = Subscriptions.create(() -> System.out.println("Clean"));

s.unsubscribe();Clean

Subscriptions.create takes an action that will be executed on unsubscription to release the resources. There also are shorthand for common actions when creating a sequence.

Subscriptions.empty()returns aSubscriptionthat does nothing when disposed. This is useful when you are required to return an instance ofSubscription, but your implementation doesn't actually need to release any resources.Subscriptions.from(Subscription... subscriptions)returns aSubscriptionthat will dispose of multiple other subscriptions when it is disposed.Subscriptions.unsubscribed()returns aSubscriptionthat is already disposed of.

There are several implementations of Subscription.

BooleanSubscriptionCompositeSubscriptionMultipleAssignmentSubscriptionRefCountSubscriptionSafeSubscriberScheduler.WorkerSerializedSubscriberSerialSubscriptionSubscriberTestSubscriber

We will see more of them later in this book. It is interesting to note that Subscriber also implements Subscription. This means that we can also use a reference to a Subscriber to terminate a subscription.

Now that you understand what Rx is in general, it is time to start creating and manipulating sequences. The original implementation of manipulating sequences was based on C#'s LINQ, which in turn was inspired from functional programming. Knowledge about either isn't necessary, but it would make the learning process a lot easier for the reader. Following the original www.introtorx.com, we too will divide operations into themes that generally go from the simpler to the more advanced. Most Rx operators manipulate existing sequences. But first, we will see how to create an Observable to begin with.

In previous examples we used Subjects and manually pushed values into them to create a sequence. We used that sequence to demonstrate some key concepts and the first and most important Rx method, subscribe. In most cases, subjects are not the best way to create a new Observable. We will now see tidier ways to create observable sequences.

The just method creates an Observable that will emit a predifined sequence of values, supplied on creation, and then terminate.

Observable<String> values = Observable.just("one", "two", "three");

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Received: one

Received: two

Received: three

Completed

This observable will emit a single onCompleted and nothing else.

Observable<String> values = Observable.empty();

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Completed

This observable will never emit anything

Observable<String> values = Observable.never();

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);The code above will print nothing. Note that this doesn't mean that the program is blocking. In fact, it will terminate immediately.

This observable will emit a single error event and terminate.

Observable<String> values = Observable.error(new Exception("Oops"));

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Error: java.lang.Exception: Oops

defer doesn't define a new kind of observable, but allows you to declare how an observable should be created every time a subscriber arrives. Consider how you would create an observable that returns the current time and terminates. You are emitting a single value, so it sounds like a case for just.

Observable<Long> now = Observable.just(System.currentTimeMillis());

now.subscribe(System.out::println);

Thread.sleep(1000);

now.subscribe(System.out::println);1431443908375

1431443908375

Notice how the two subscribers, 1 second apart, see the same time. That is because the value for the time is aquired once: when execution reaches just. What you want is for the time to be aquired when a subscriber asks for it by subscribing. defer takes a function that will executed to create and return the Observable. The Observable returned by the function is also the Observable returned by defer. The important thing here is that this function will be executed again for every new subscription.

Observable<Long> now = Observable.defer(() ->

Observable.just(System.currentTimeMillis()));

now.subscribe(System.out::println);

Thread.sleep(1000);

now.subscribe(System.out::println);1431444107854

1431444108858

create is a very powerful function for creating observables. Let have a look at the signature.

static <T> Observable<T> create(Observable.OnSubscribe<T> f)The Observable.OnSubscribe<T> is simpler than it looks. It is basically a function that takes a Subscriber<T> for type T. Inside it we can manually determine the events that are pushed to the subscriber.

Observable<String> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext("Hello");

o.onCompleted();

});

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Received: Hello

Completed

When someone subscribes to the observable (here: values), the corresponding Subscriber instance is passed to your function. As the code is executed, values are being pushed to the subscriber. Note that you have to call onCompleted in the end by yourself, if you want the sequence to signal its completion.

This method should be your preferred way of creating a custom observable, when none of the existing shorthands serve your purpose. The code is similar to how we created a Subject and pushed values to it, but there are a few important differences. First of all, the source of the events is neatly encapsulated and separated from unrelated code. Secondly, Subjects carry dangers that are not obvious: with a Subject you are managing state, and anyone with access to the instance can push values into it and alter the sequence. We will see more about this issue later on.

Another key difference to using subjects is that the code is executed lazily, when and if an observer subscribes. In the example above, the code is run not when the observable is created (because there is no Subscriber yet), but each time subscribe is called. This means that every value is generated again for each subscriber, similar to ReplaySubject. The end result is similar to a ReplaySubject, except that no caching takes place. However, if we had used a ReplaySubject, and the creation method was time-consuming, that would block the thread that executes the creation. You'd have to manually create a new thread to push values into the Subject. We're not presenting Rx's methods for concurrency yet, but there are convenient ways to make the execution of the onSubscribe function concurrently.

You may have already noticed that you can trivially implement any of the previous observables using Observable.create. In fact, our example for create is equivalent to Observable.just("hello").

In functional programming it is common to create sequences of unrestricted or infinite length. RxJava has factory methods that create such sequences.

A straight forward and familiar method to any functional programmer. It emits the specified range of integers.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(10, 15);The example emits the values from 10 to 24 in sequence.

This function will create an infinite sequence of ticks, separated by the specified time duration.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(1000, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);

System.in.read();Received: 0

Received: 1

Received: 2

Received: 3

...

This sequence will not terminate until we unsubscribe.

We should note why the blocking read at the end is necessary. Without it, the program terminates without printing something. That's because our operations are non-blocking: we create an observable that will emit values over time, then we register the actions to execute if and when values arrive. None of that is blocking and the main thread proceeds to terminate. The timer that produces the ticks runs on its own thread, which does not prevent the JVM from terminating, killing the timer with it.

There are two overloads to Observable.timer. The first example creates an observable that waits a given amount of time, then emits 0L and terminates.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.timer(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Received: 0

Completed

The second one will wait a specified amount of time, then begin emitting like interval with the given frequency.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.timer(2, 1, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Received: 0

Received: 1

Received: 2

...

The example above waits 2 seconds, then starts counting every 1 second.

There are well established tools for dealing with sequences, collections and asychronous events, which may not be directly compatible with Rx. Here we will discuss ways to turn their output into input for your Rx code.

If you are using an asynchronous tool that uses event handlers, like JavaFX, you can use Observable.create to turn the streams into an observable

Observable<ActionEvent> events = Observable.create(o -> {

button2.setOnAction(new EventHandler<ActionEvent>() {

@Override public void handle(ActionEvent e) {

o.onNext(e)

}

});

})Depending on what the event is, the event type (here ActionEvent) may be meaningful enough to be the type of your sequence. Very often you will want something else, like the contents of a field. The place to get the value is in the handler, while the GUI thread is blocked by the handler and the field value is relevant. There is no guarantee what the value will be by the time the value reaches the final Subscriber. On the other hand, a value moving though an observable should remain unchanged, if the pipeline is properly implemented.

Much like most of the functions we've seen so far, you can turn any kind of input into an Rx observable with create. There are several shorthands for converting common types of input.

Futures are part of the Java framework and you may come across them while using frameworks that use concurrency. They are a less powerful concept for concurrency than Rx, since they only return one value. Naturally, you'd like to them into observables.

FutureTask<Integer> f = new FutureTask<Integer>(() -> {

Thread.sleep(2000);

return 21;

});

new Thread(f).start();

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.from(f);

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Received: 21

Completed

The observable emits the result of the FutureTask when it is available and then terminates. If the task is canceled, the observable will emit a java.util.concurrent.CancellationException error.

If you're interested in the results of the Future for a limited amount of time, you can provide a timeout period like this

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.from(f, 1000, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);If the Future has not completed the specified amount of time, the observable will ignore it and fail with a TimeoutException.

You can also turn any collection into an observable using the overloads of Observable.from that take arrays and iterables. This will result in every item in the collection being emitted and then a final onCompleted event.

Integer[] is = {1,2,3};

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.from(is);

Subscription subscription = values.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("Received: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Received: 1

Received: 2

Received: 3

Completed

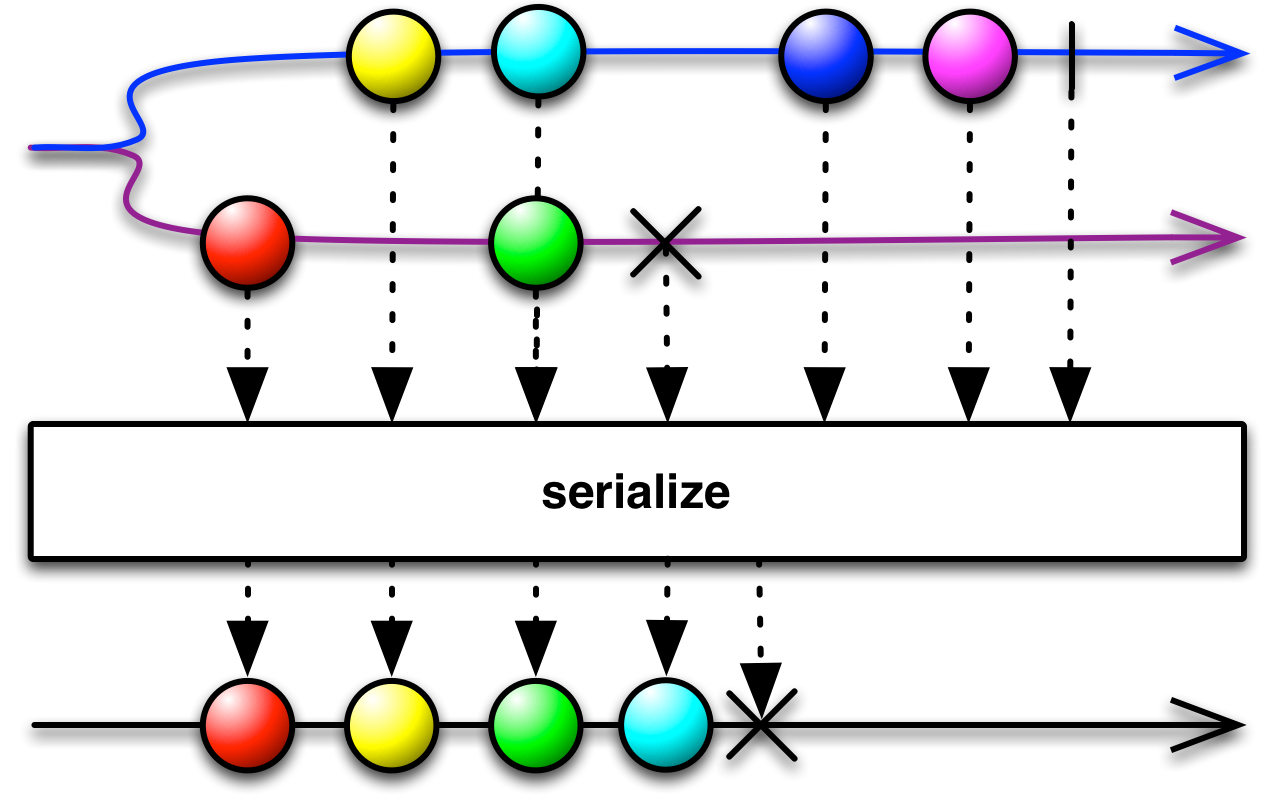

Observable is not interchangeable with Iterable or Stream. Observables are push-based, i.e., the call to onNext causes the stack of handlers to execute all the way to the final subscriber method (unless specified otherwise). The other models are pull-based, which means that values are requested as soon as possible and execution blocks until the result is returned.

The examples we've seen so far were all very small. Nothing should stop you from using Rx on a huge stream of realtime data, but what good would Rx be if it dumped the whole bulk of the data onto you, and force you handle it like you would otherwise? Here we will explore operators that can filter out irrelevant data, or reduce the data to the single value that you want.

Most of the operators here will be familiar to anyone who has worked with Java's Streams or functional programming in general. All the operators here return a new observable and do not affect the original observable. This principle is present throughout Rx. Transformations of observables create a new observable every time and leave the original unaffected. Subscribers to the original observable should notice no change, but we will see in later chapters that guaranteeing this may require caution from the developer as well.

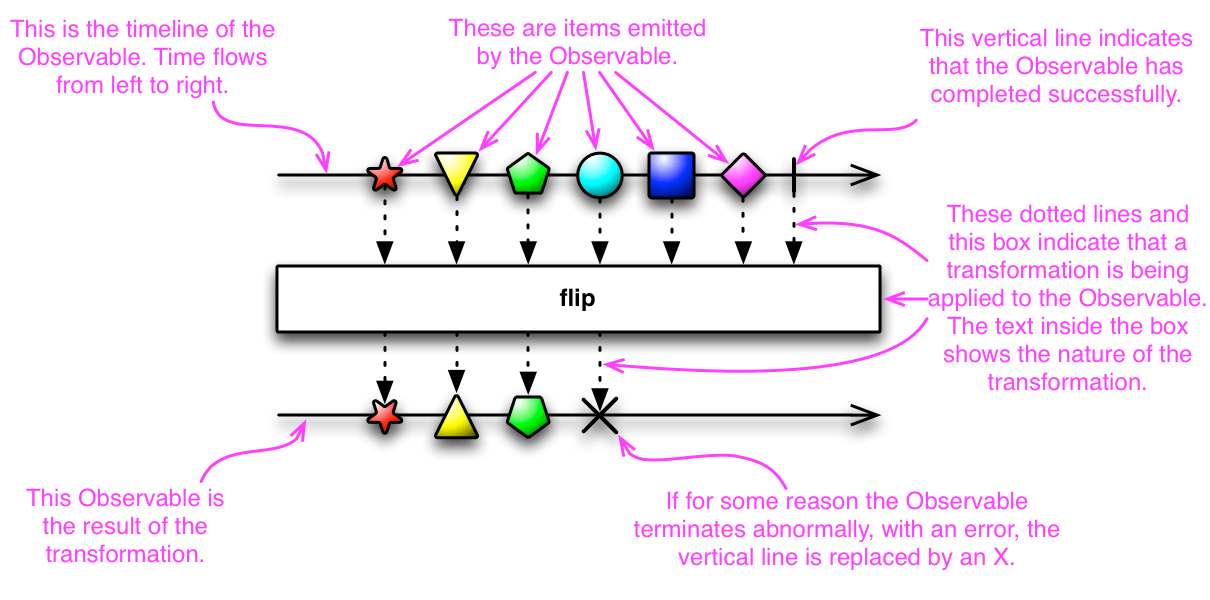

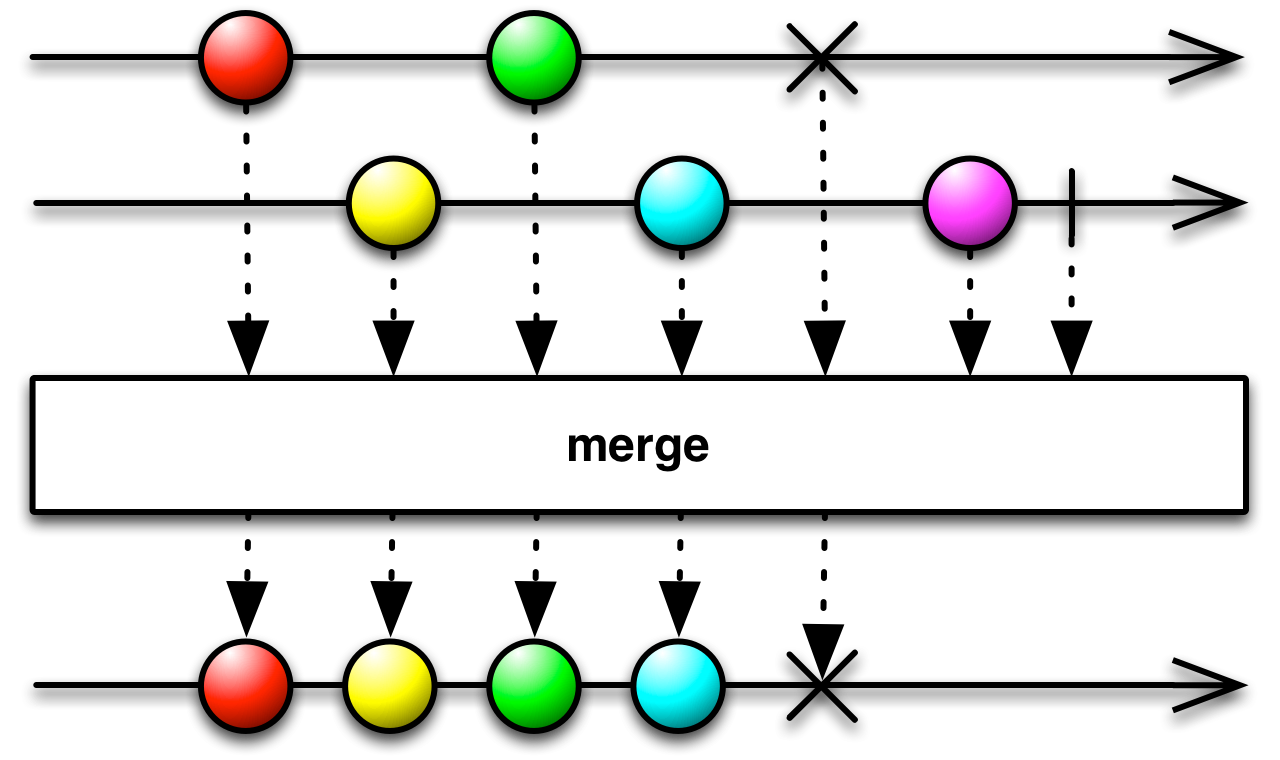

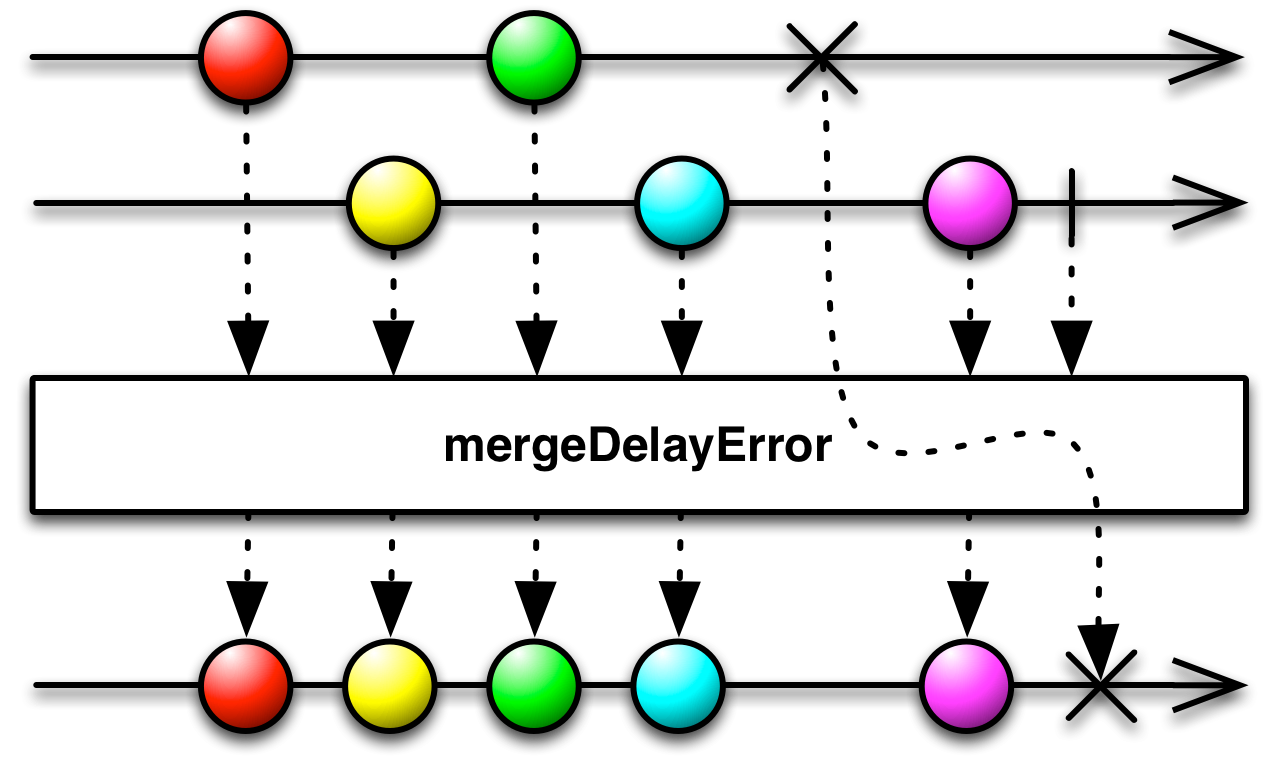

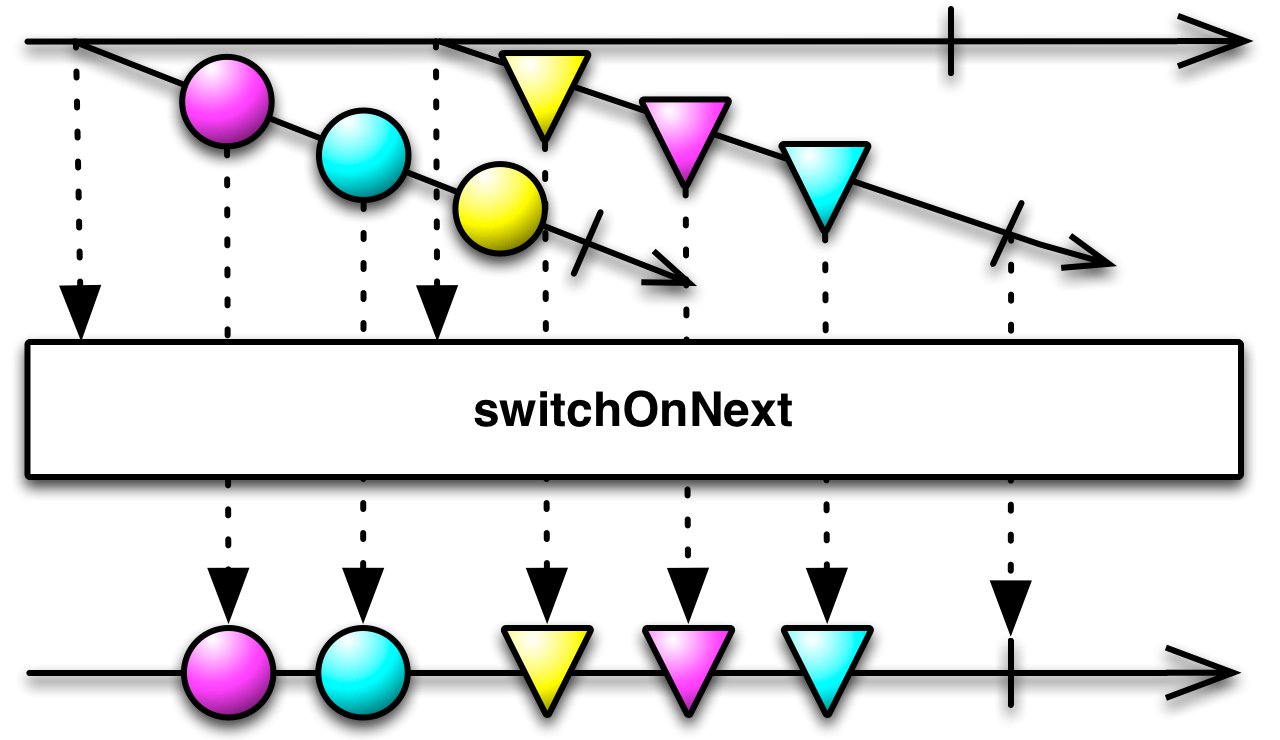

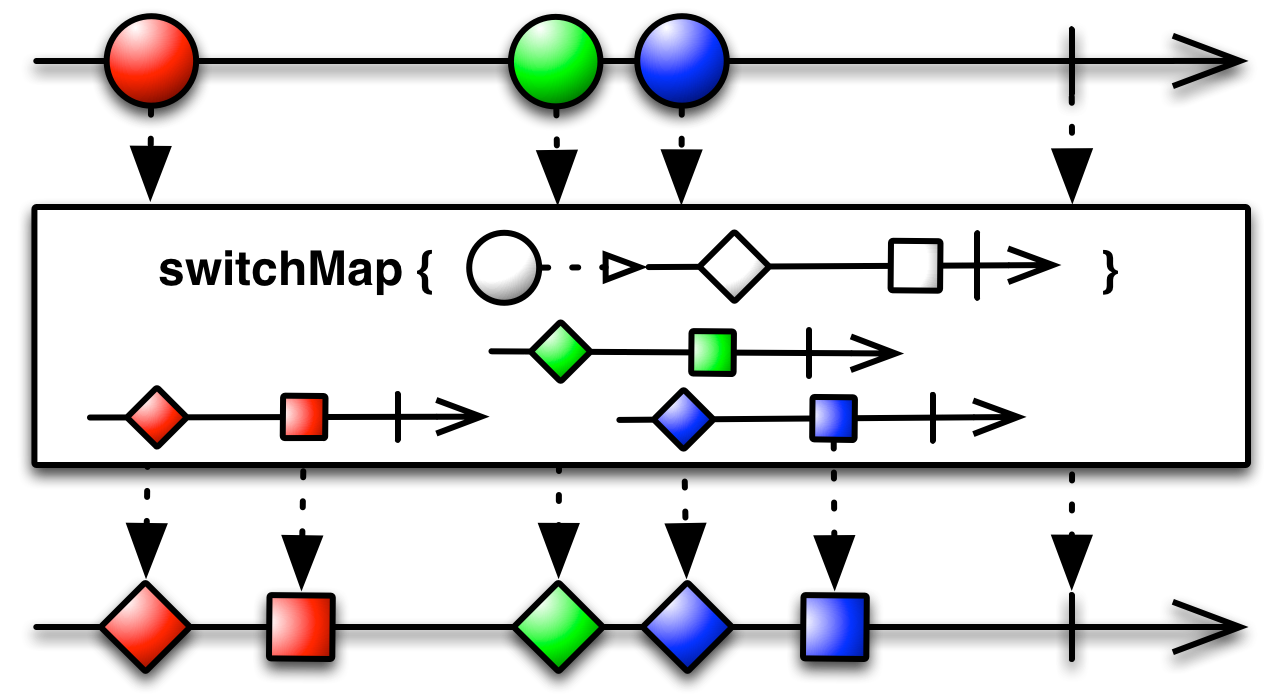

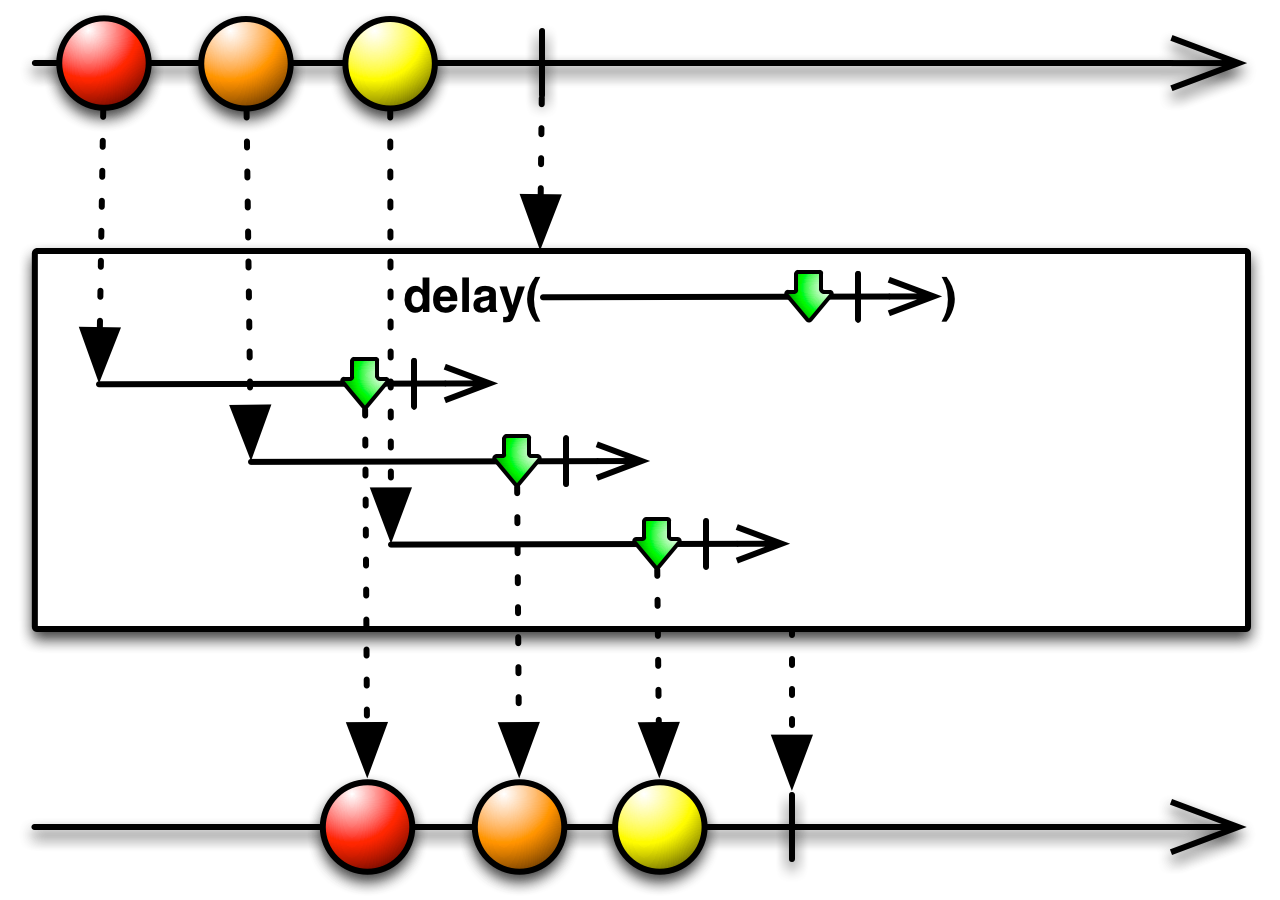

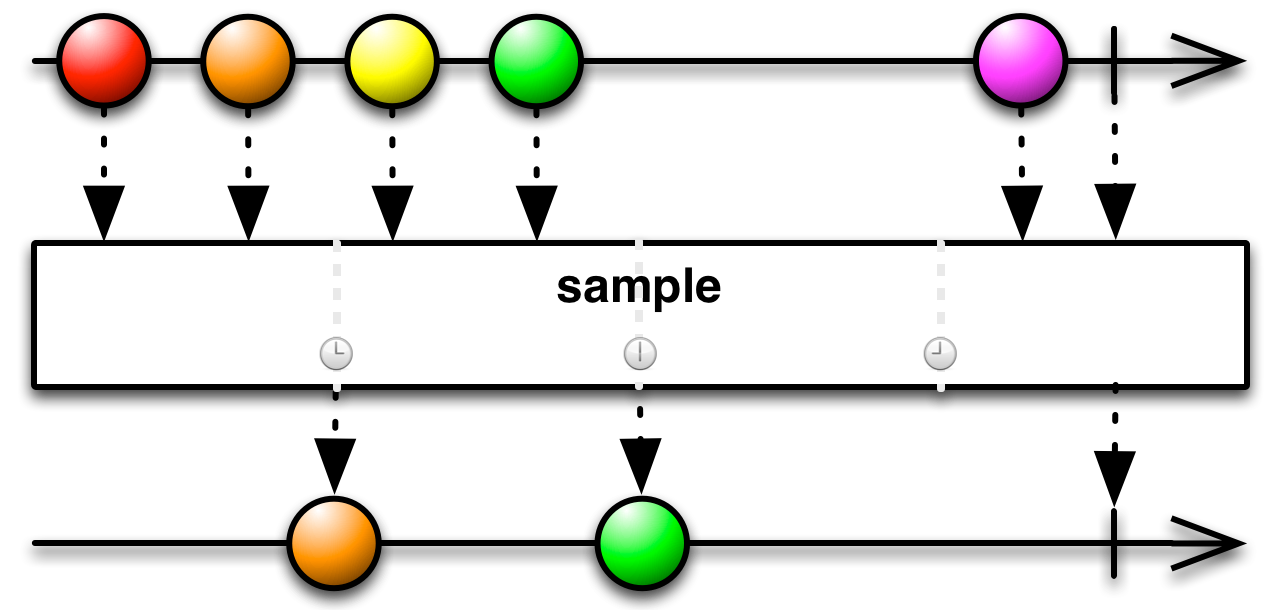

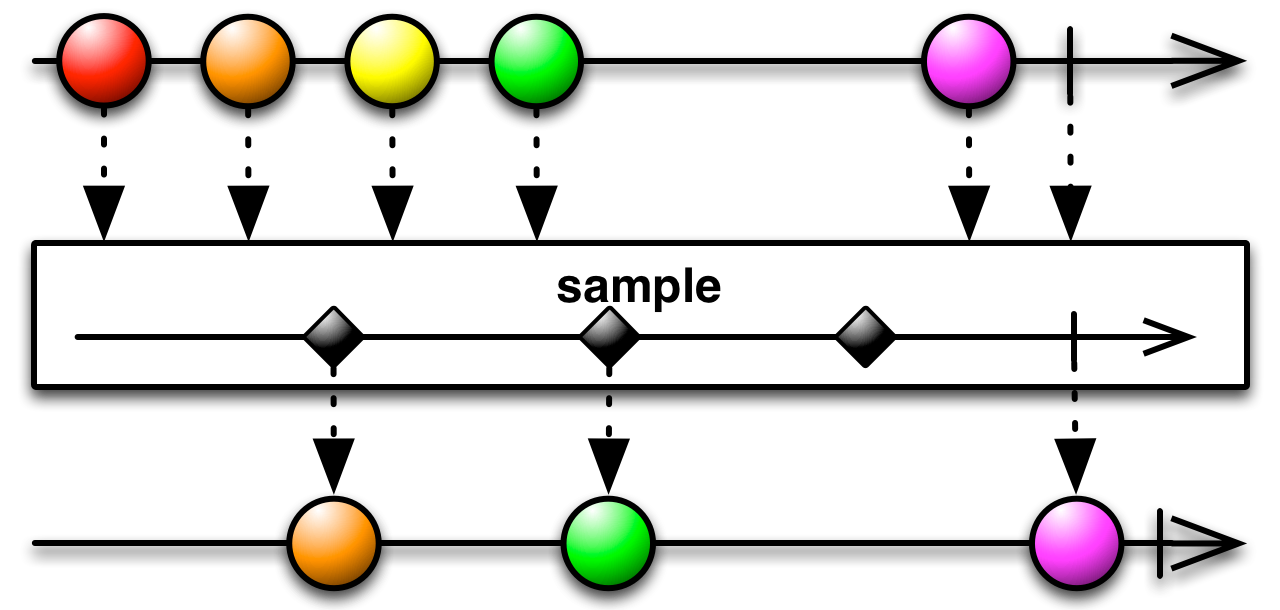

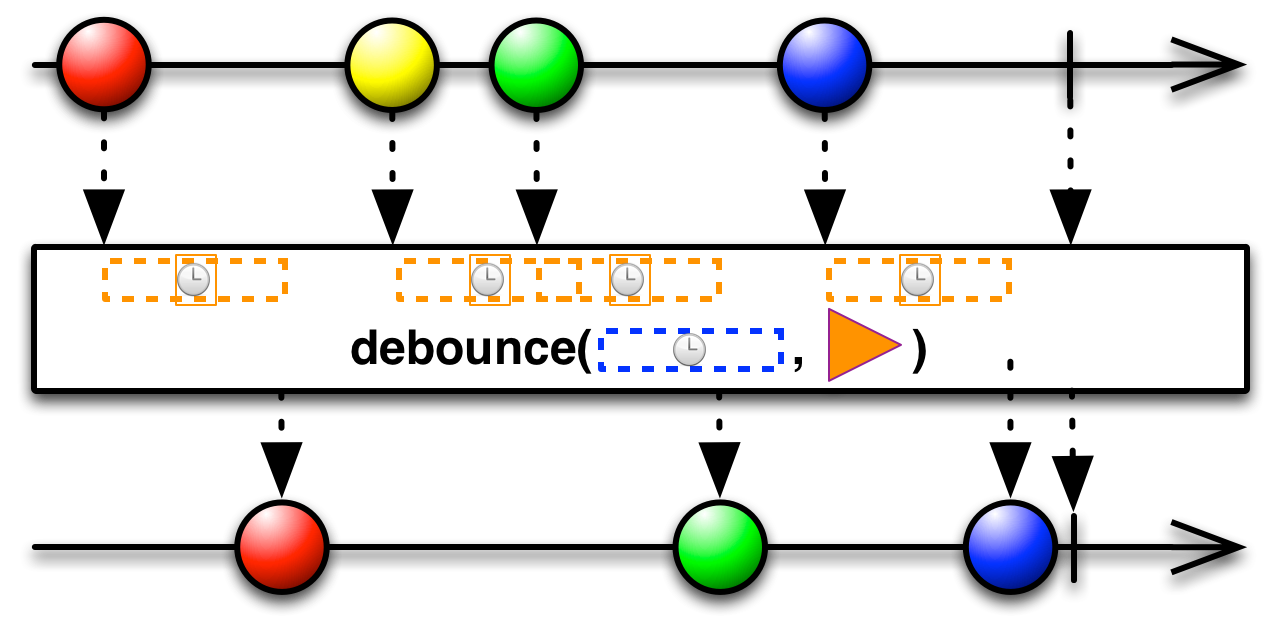

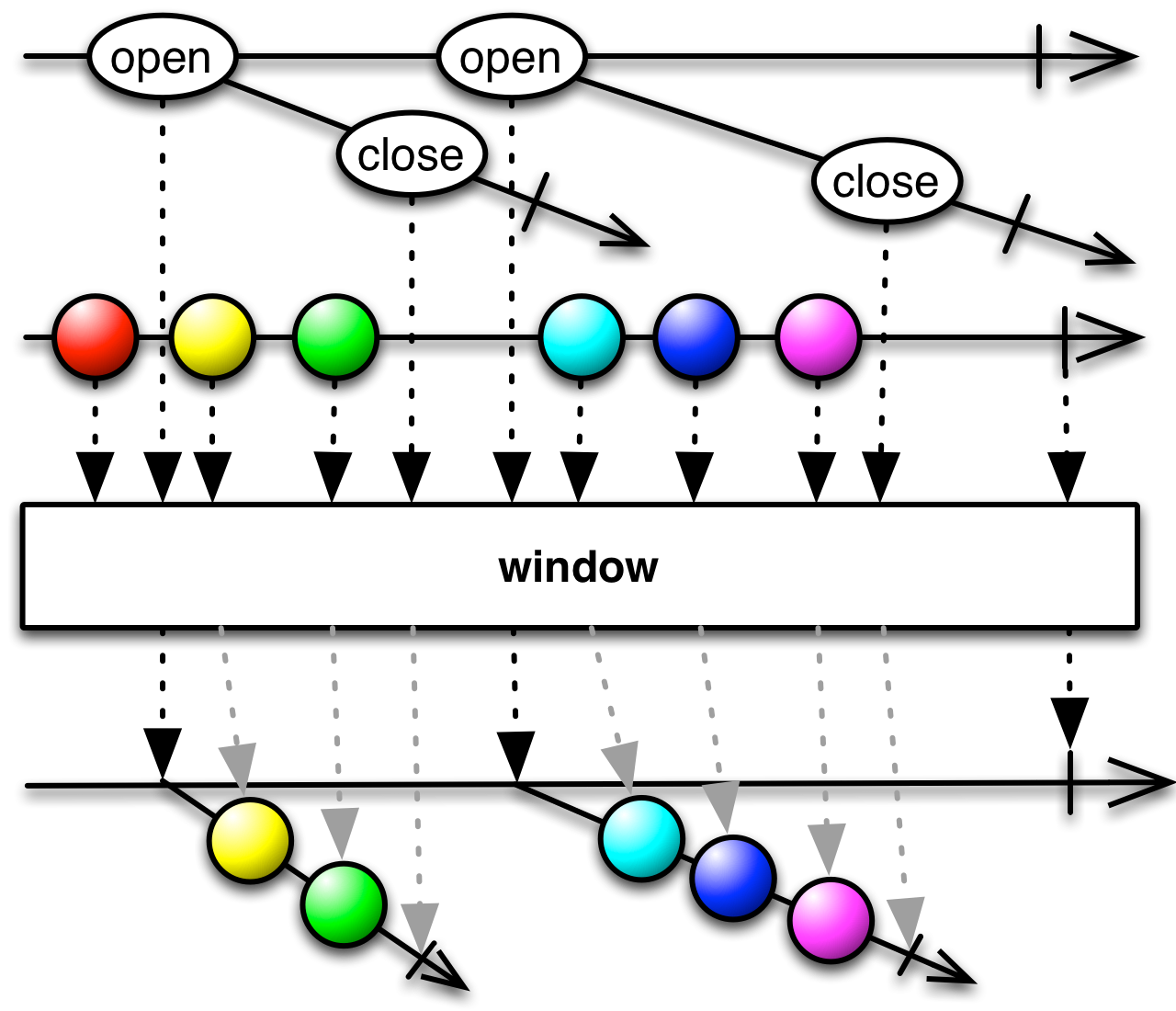

This is an appropriate time to introduce to concept of marble diagrams. It is a popular way of explaining the operators in Rx, because of their intuitive and graphical nature. They are present a lot in the documentation of RxJava and it only makes sense that we take advantage of their explanatory nature. The format is mostly self-explanatory: time flows left to right, shapes represent values, a slash is a onCompletion, an X is an error. The operator is applied to the top sequence and the result is the sequence below.

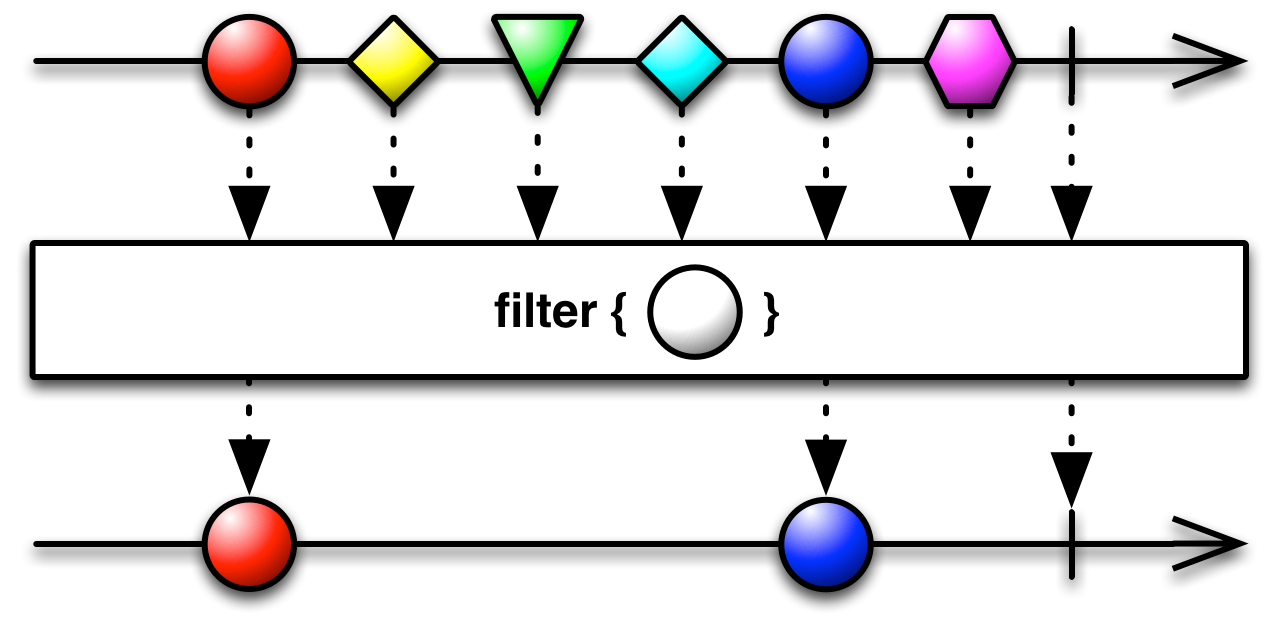

filter takes a predicate function that makes a boolean decision for each value emitted. If the decision is false, the item is omitted from the filtered sequence.

public final Observable<T> filter(Func1<? super T,java.lang.Boolean> predicate)We will use filter to create a sequence of numbers and filter out all the even ones, keeping only odd values.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0,10);

Subscription oddNumbers = values

.filter(v -> v % 2 == 0)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

2

4

6

8

Completed

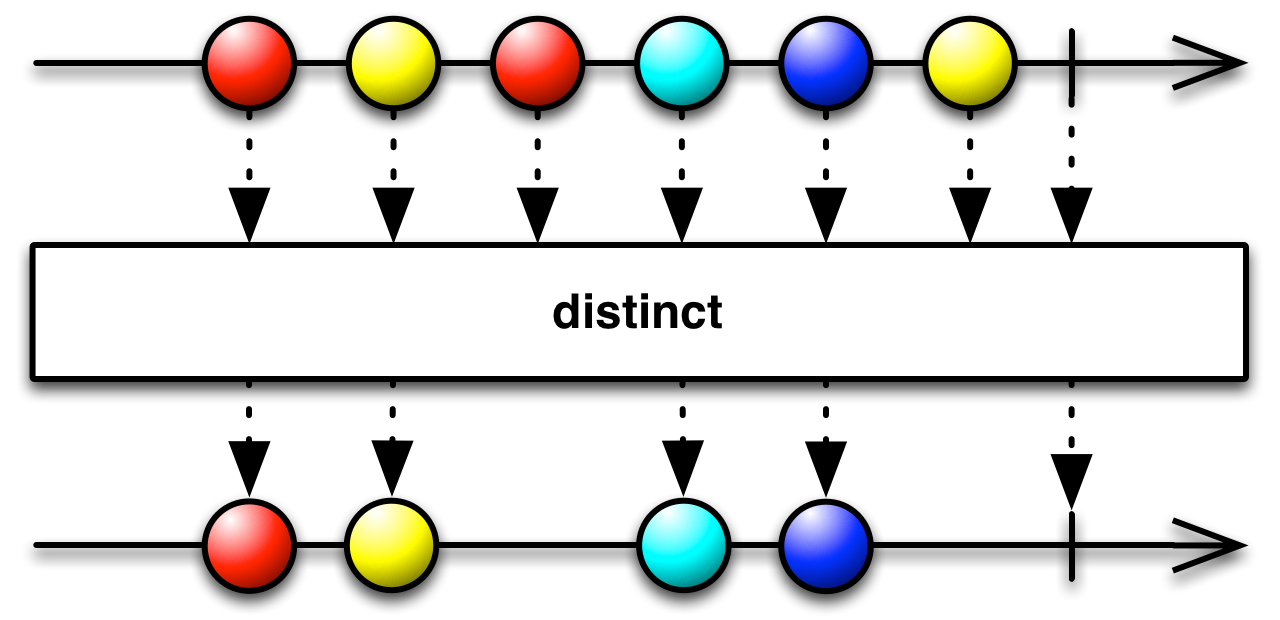

distinct filters out any element that has already appeared in the sequence.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(1);

o.onNext(1);

o.onNext(2);

o.onNext(3);

o.onNext(2);

o.onCompleted();

});

Subscription subscription = values

.distinct()

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);1

2

3

Completed

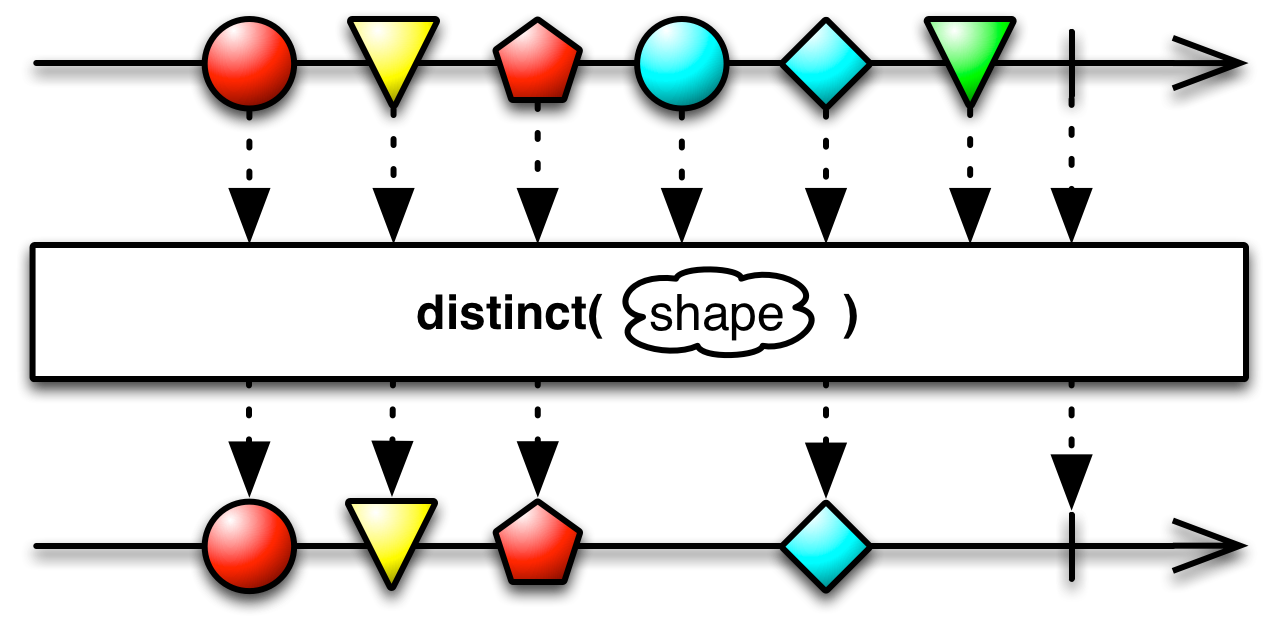

An overload of distinct takes a key selector. For each item, the function generates a key and the key is then used to determine distinctiveness.

public final <U> Observable<T> distinct(Func1<? super T,? extends U> keySelector)In this example, we use the first character as a key.

Observable<String> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext("First");

o.onNext("Second");

o.onNext("Third");

o.onNext("Fourth");

o.onNext("Fifth");

o.onCompleted();

});

Subscription subscription = values

.distinct(v -> v.charAt(0))

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);First

Second

Third

Completed

"Fourth" and "Fifth" were filtered out because their first character is 'F' and that has already appeared in "First".

An experienced programmer already knows that this operator maintains a set internally with every unique value that passes through the observable and checks every new value against it. While Rx operators neatly hide these things, you should still be aware that an Rx operator can have a significant cost and consider what you are using it on.

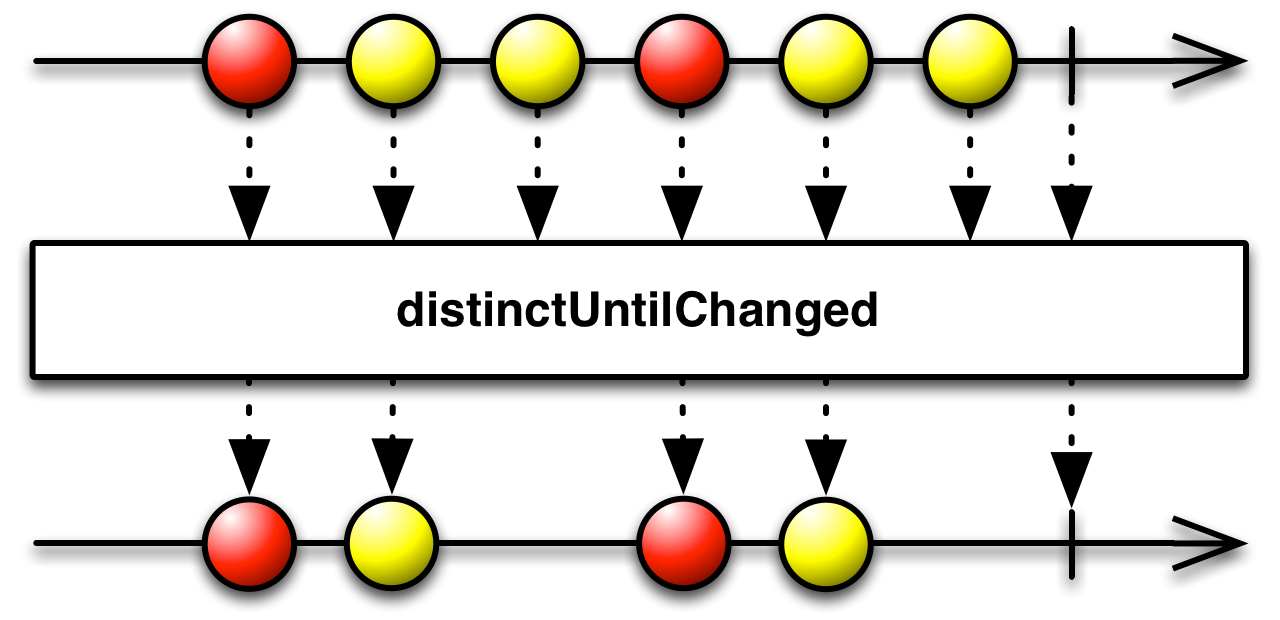

A variant of distinct is distinctUntilChanged. The difference is that only consecutive non-distinct values are filtered out.

public final Observable<T> distinctUntilChanged()

public final <U> Observable<T> distinctUntilChanged(Func1<? super T,? extends U> keySelector)Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(1);

o.onNext(1);

o.onNext(2);

o.onNext(3);

o.onNext(2);

o.onCompleted();

});

Subscription subscription = values

.distinctUntilChanged()

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);1

2

3

2

Completed

You can you use a key selector with distinctUntilChanged, as well.

Observable<String> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext("First");

o.onNext("Second");

o.onNext("Third");

o.onNext("Fourth");

o.onNext("Fifth");

o.onCompleted();

});

Subscription subscription = values

.distinctUntilChanged(v -> v.charAt(0))

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);First

Second

Third

Fourth

Completed

ignoreElements will ignore every value, but lets pass through onCompleted and onError.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0, 10);

Subscription subscription = values

.ignoreElements()

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Completed

ignoreElements() produces the same result as filter(v -> false)

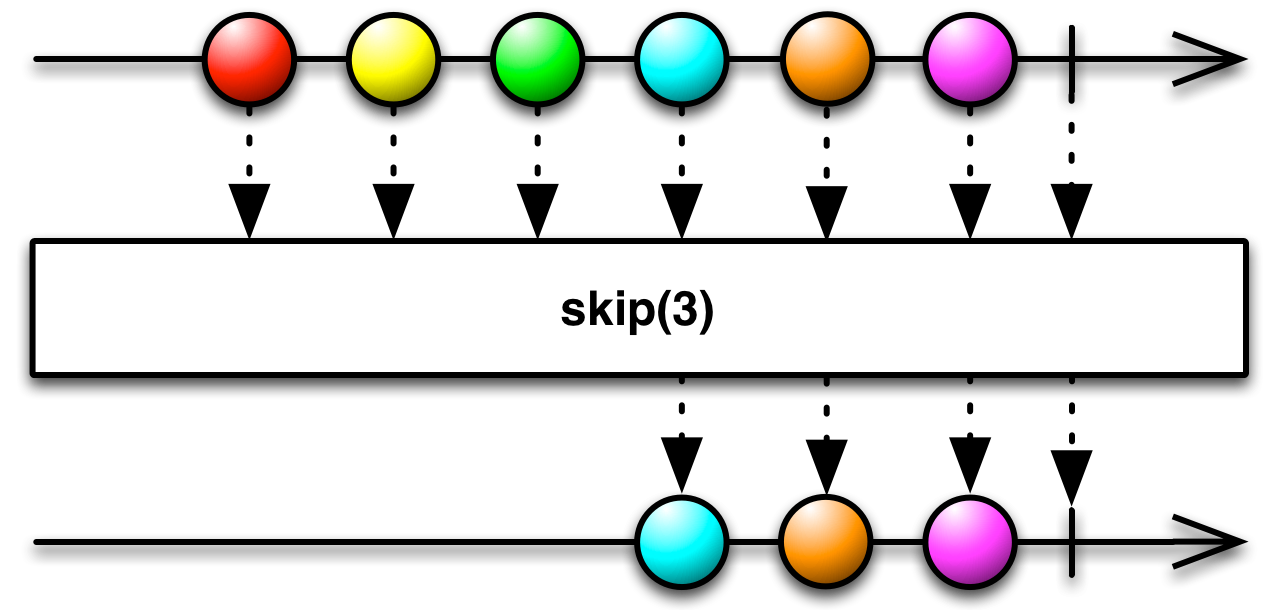

The next group of methods serve to cut the sequence at a specific point based on the item's index, and either take the first part or the second part. take takes the first n elements, while skip skips them. Note that neither function considers it an error if there are fewer items in the sequence than the specified index.

Observable<T> take(int num)Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0, 5);

Subscription first2 = values

.take(2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

1

Completed

Users of Java 8 streams should know the take operator as limit. The limit operator exists in Rx too, for symmetry purposes. It is an alias of take, but it lacks the richer overloads that we will soon see.

take completes as soon as the n-th item is available. If an error occurs, the error will be forwarded, but not if it occurs after the cutting point. take doesn't care what happens in the observable after the n-th item.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(1);

o.onError(new Exception("Oops"));

});

Subscription subscription = values

.take(1)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);1

Completed

skip returns the other half of a take.

Observable<T> skip(int num)Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0, 5);

Subscription subscription = values

.skip(2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);2

3

4

Completed

There are overloads where the cutoff is a moment in time rather than place in the sequence.

Observable<T> take(long time, java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit unit)

Observable<T> skip(long time, java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit unit)Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.take(250, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

1

Completed

take and skip work with predefined indices. If you want to "discover" the cutoff point as the values come, takeWhile and skipWhile will use a predicate instead. takeWhile takes items while a predicate function returns true

Observable<T> takeWhile(Func1<? super T,java.lang.Boolean> predicate)Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.takeWhile(v -> v < 2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

1

Completed

As you would expect, skipWhile returns the other half of the sequence

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.skipWhile(v -> v < 2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);2

3

4

...

skipLast and takeLast work just like take and skip, with the difference that the point of reference is from the end.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0,5);

Subscription subscription = values

.skipLast(2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

1

2

Completed

By now you should be able to guess how takeLast is related to skipLast. There are overloads for both indices and time.

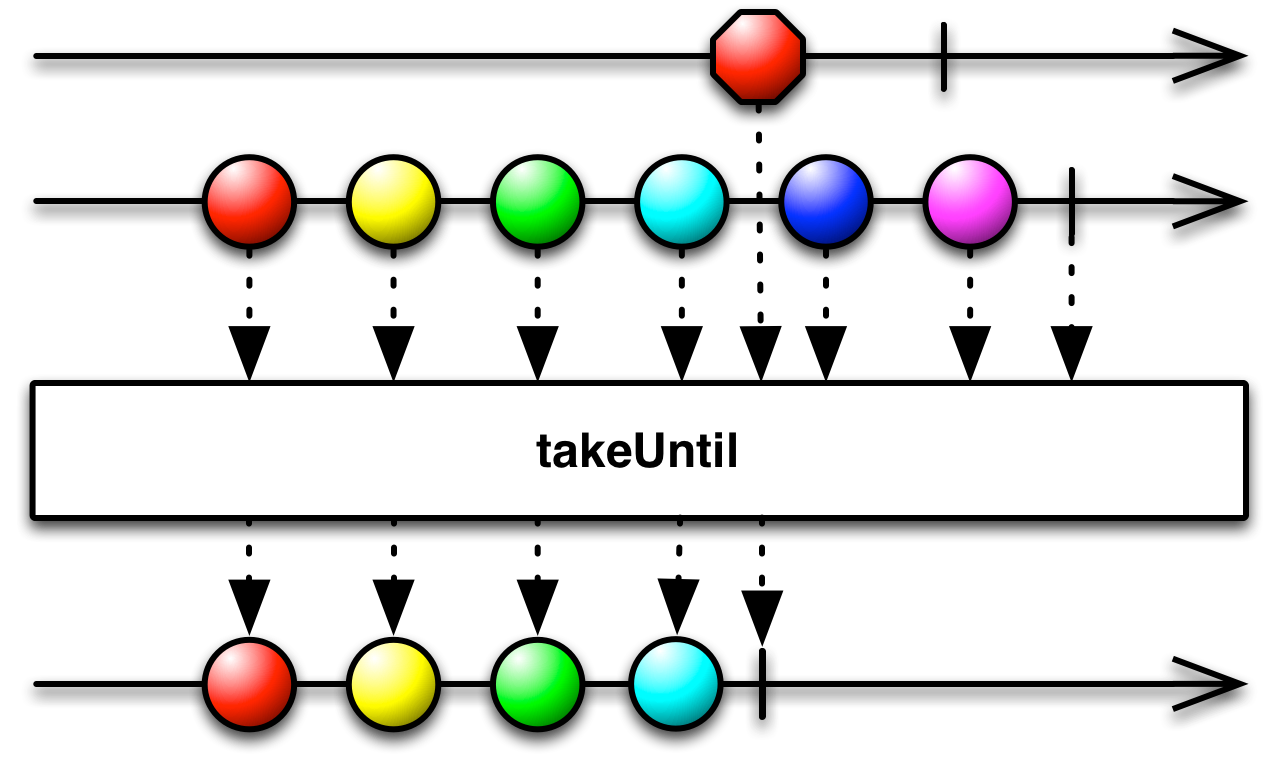

There are also two methods named takeUntil and skipUntil. takeUntil works exactly like takeWhile except that it takes items while the predictate is false. The same is true of skipUntil.

Along with that, takeUntil and skipUntil each have a very interesting overload. The cutoff point is defined as the moment when another observable emits an item.

public final <E> Observable<T> takeUntil(Observable<? extends E> other)Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100,TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Observable<Long> cutoff = Observable.timer(250, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.takeUntil(cutoff)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

1

Completed

As you may remember, timer here will wait 250ms and emit one event. This signals takeUntil to stop the sequence. Note that the signal can be of any type, since the actual value is not used.

Once again skipUntil works by the same rules and returns the other half of the observable. Values are ignored until the signal comes to start letting values pass through.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100,TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Observable<Long> cutoff = Observable.timer(250, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.skipUntil(cutoff)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);2

3

4

...

In the previous chapter we just saw ways to filter out data that we don't care about. Sometimes what we want is information about the sequence rather than the values themselves. We will now introduce some methods that allow us to reason about a sequence.

The all method establishes that every value emitted by an observable meets a criterion. Here's the signature and an example:

public final Observable<java.lang.Boolean> all(Func1<? super T,java.lang.Boolean> predicate)Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(0);

o.onNext(10);

o.onNext(10);

o.onNext(2);

o.onCompleted();

});

Subscription evenNumbers = values

.all(i -> i % 2 == 0)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);true

Completed

An interesting fact about this method is that it returns an observable with a single value, rather than the boolean value directly. This is because it is unknown how long it will take to establish whether the result should be true or false. Even though it completes as soon as it can know, that may take as long the source sequence itself. As soon as an item fails the predicate, false will be emitted. A value of true on the other hand cannot be emitted until the source sequence has completed and all of the items are checked. Returning the decision inside an observable is a convenient way of making the operation non-blocking. We can see all failing as soon as possible in the next example:

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(150, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS).take(5);

Subscription subscription = values

.all(i -> i<3) // Will fail eventually

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println("All: " + v),

e -> System.out.println("All: Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("All: Completed")

);

Subscription subscription2 = values

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

1

2

All: false

All: Completed

3

4

Completed

If the source observable emits an error, then all becomes irrelevant and the error passes through, terminating the sequence.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(0);

o.onNext(2);

o.onError(new Exception());

});

Subscription subscription = values

.all(i -> i % 2 == 0)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Error: java.lang.Exception

If, however, the predicate fails, then false is emitted and the sequence terminates. Even if the source observable fails after that, the event is ignored, as required by the Rx contract (no events after a termination event).

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(1);

o.onNext(2);

o.onError(new Exception());

});

Subscription subscription = values

.all(i -> i % 2 == 0)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);false

Completed

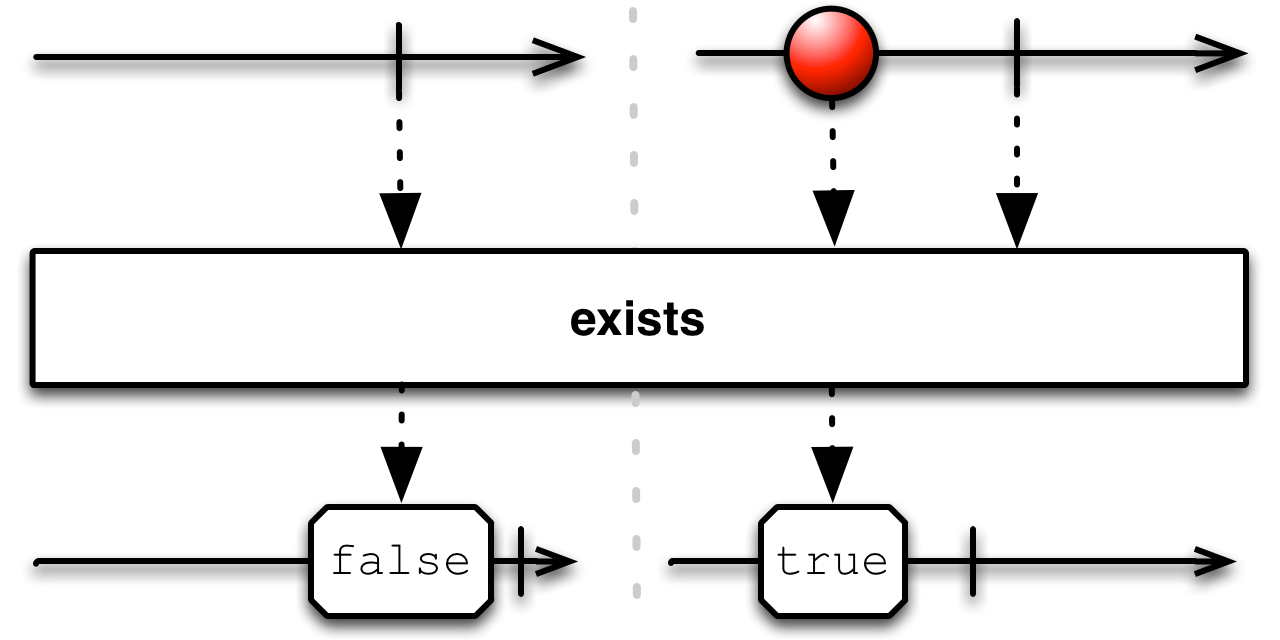

The exists method returns an observable that will emit true if any of the values emitted by the observable make the predicate true.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0, 2);

Subscription subscription = values

.exists(i -> i > 2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);false

Completed

Here our range didn't go high enough for the i > 2 condition to succeed. If we extend our range in the same example with

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0, 4);We will get a successful result

true

Completed

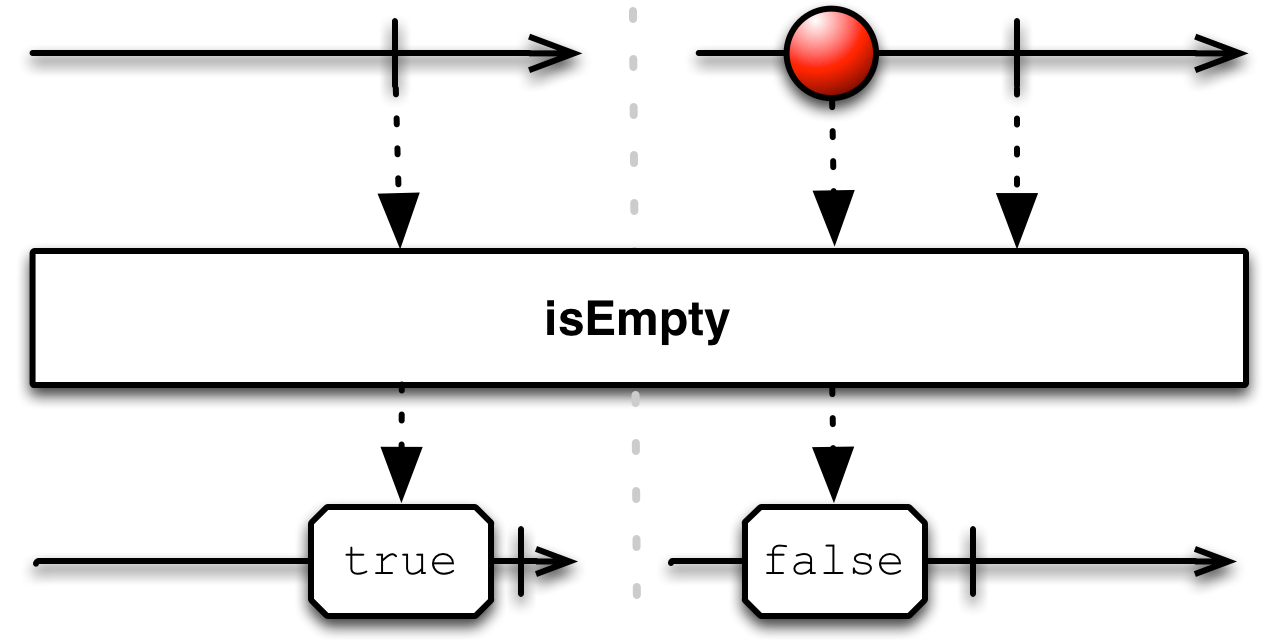

This operator's result is a boolean value, indicating if an observable emitted values before completing or not.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.timer(1000, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.isEmpty()

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);false

Completed

Falsehood is established as soon as the first value is emitted. true will be returned once the source observable has terminated.

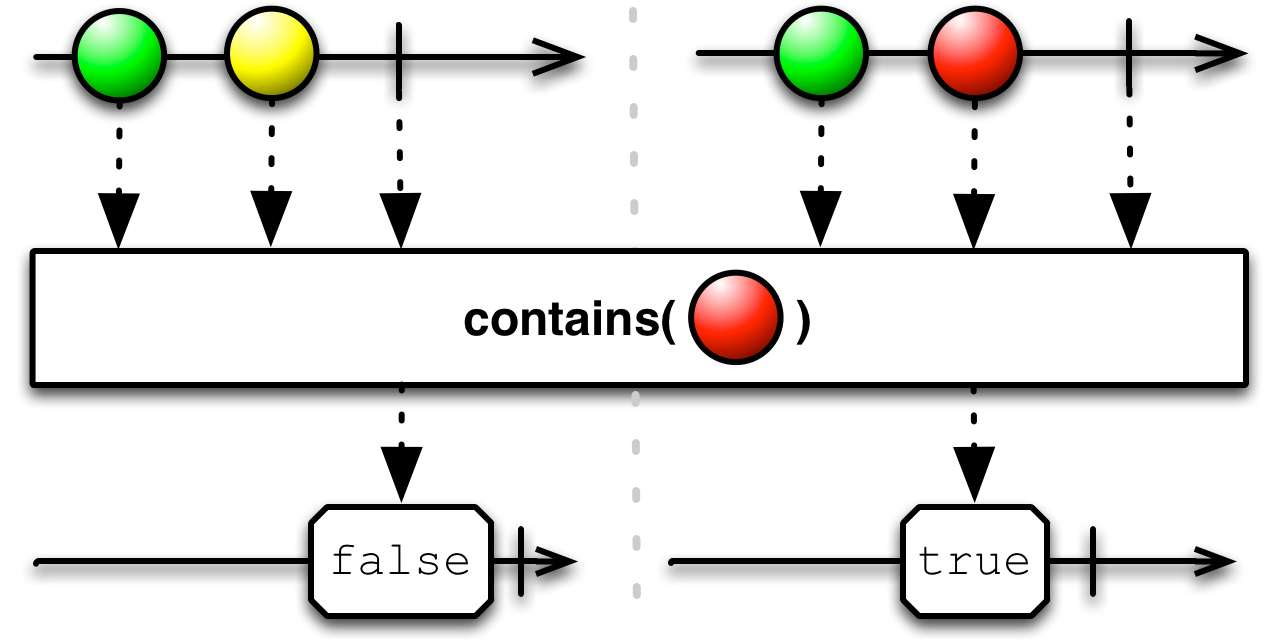

The method contains establishes if a particular element is emitted by an observable. contains will use the Object.equals method to establish the equality. Just like previous operators, it emits its decision as soon as it can be established and immediately completes.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

Subscription subscription = values

.contains(4L)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);true

Completed

If we had used contains(4) where we used contains(4L), nothing would be printed. That's because 4 and 4L are not equal in Java. Our code would wait for the observable to complete before returning false, but the observable we used is infinite.

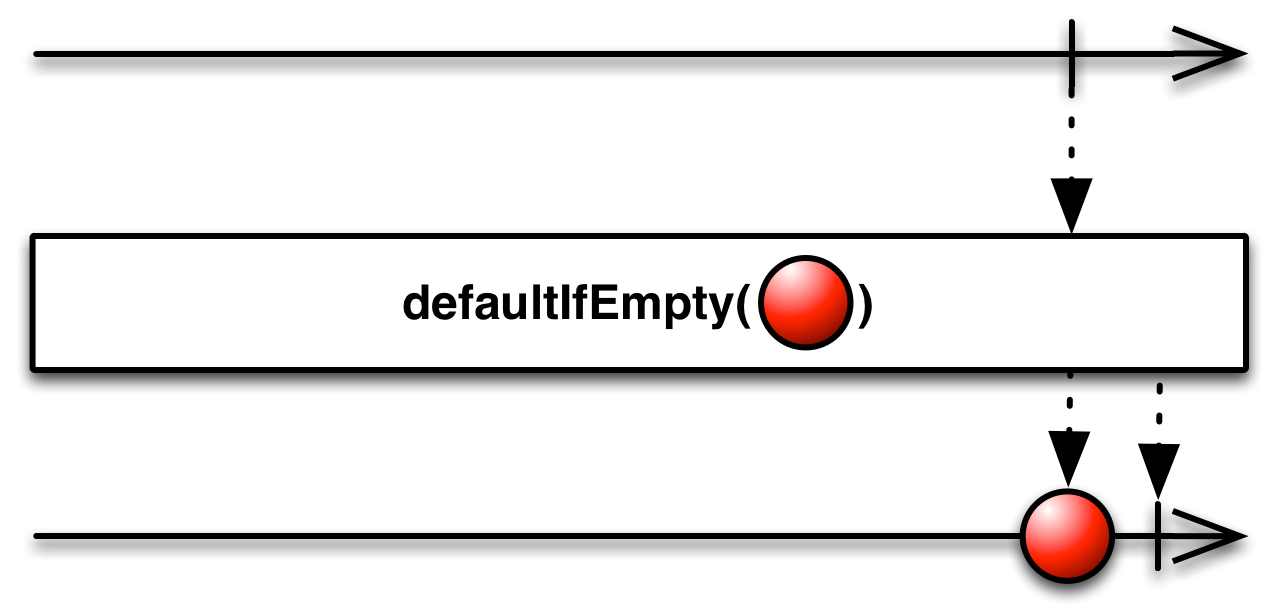

If an empty sequence would cause you problems, rather than checking with isEmpty and handling the case, you can force an observable to emit a value on completion if it didn't emit anything before completing.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.empty();

Subscription subscription = values

.defaultIfEmpty(2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);2

Completed

The default value is emitted only if no other values appeared and only on successful completion. If the source is not empty, the result is just the source observable. In the case of the error, the default value will not be emitted before the error.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.error(new Exception());

Subscription subscription = values

.defaultIfEmpty(2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Output

Error: java.lang.Exception

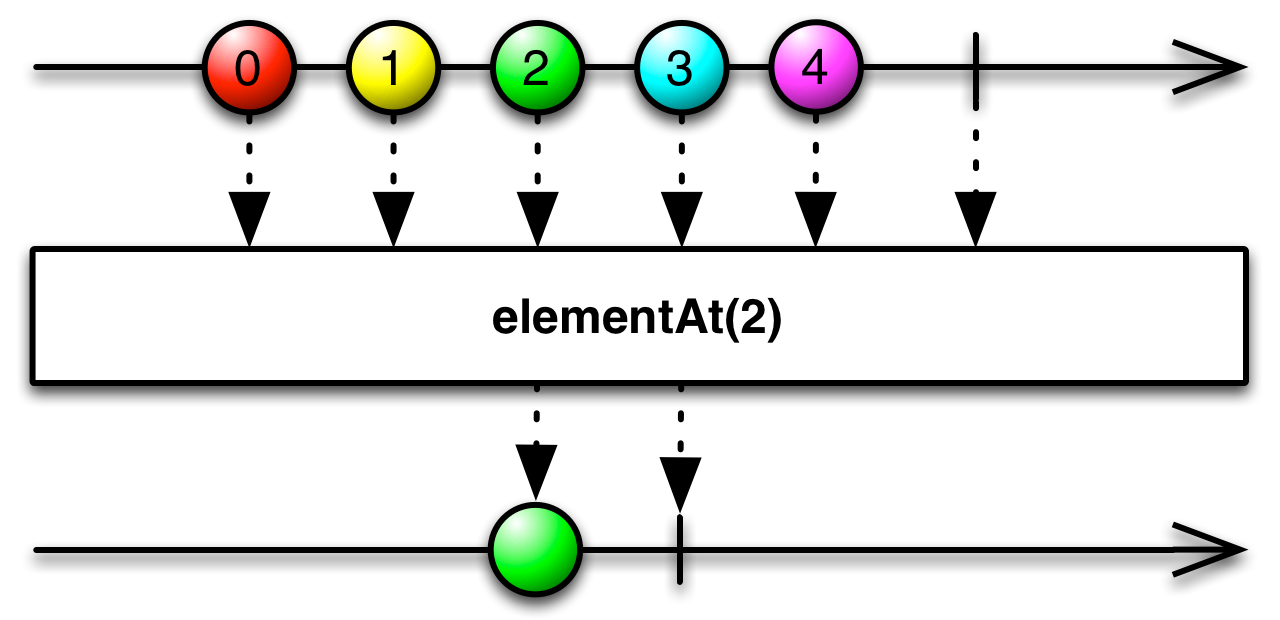

You can select exactly one element out of an observable using the elementAt method

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(100, 10);

Subscription subscription = values

.elementAt(2)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);102

Completed

If the sequence doesn't have enough items, an java.lang.IndexOutOfBoundsException will be emitted. To avoid that specific case, we can provide a default value that will be emitted instead of an IndexOutOfBoundsException.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(100, 10);

Subscription subscription = values

.elementAtOrDefault(22, 0)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);0

Completed

The last operator for this chapter establishes that two sequences are equal by comparing the values at the same index. Both the size of the sequences and the values must be equal. The function will either use Object.equals or the function that you supply to compare values.

Observable<String> strings = Observable.just("1", "2", "3");

Observable<Integer> ints = Observable.just(1, 2, 3);

Observable.sequenceEqual(strings, ints, (s,i) -> s.equals(i.toString()))

//Observable.sequenceEqual(strings, ints)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);true

Completed

If we swap the operator for the one that is commented out, i.e, the one using the standard Object.equals, the result would be false.

Failing is not part of the comparison. As soon as either sequence fails, the resulting observable forwards the error.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.create(o -> {

o.onNext(1);

o.onNext(2);

o.onError(new Exception());

});

Observable.sequenceEqual(values, values)

.subscribe(

v -> System.out.println(v),

e -> System.out.println("Error: " + e),

() -> System.out.println("Completed")

);Error: java.lang.Exception

We've seen how to cut away parts of a sequence that we don't want, how to get single values and how to inspect the contents of sequence. Those things can be seen as reasoning about the containing sequence. Now we will see how we can use the data in the sequence to derive new meaningful values.

The methods we will see here resemble what is called catamorphism. In our case, it would mean that the methods consume the values in the sequence and compose them into one. However, they do not strictly meet the definition, as they don't return a single value. Rather, they return an observable that promises to emit a single value.

If you've been reading through all of the examples, you should have noticed some repetition. To do away with that and to focus on what matters, we will now introduce a custom Subscriber, which we will use in our examples.

class PrintSubscriber extends Subscriber{

private final String name;

public PrintSubscriber(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void onCompleted() {

System.out.println(name + ": Completed");

}

@Override

public void onError(Throwable e) {

System.out.println(name + ": Error: " + e);

}

@Override

public void onNext(Object v) {

System.out.println(name + ": " + v);

}

}This is a very basic implementation that prints every event to the console, along with a helpful tag.

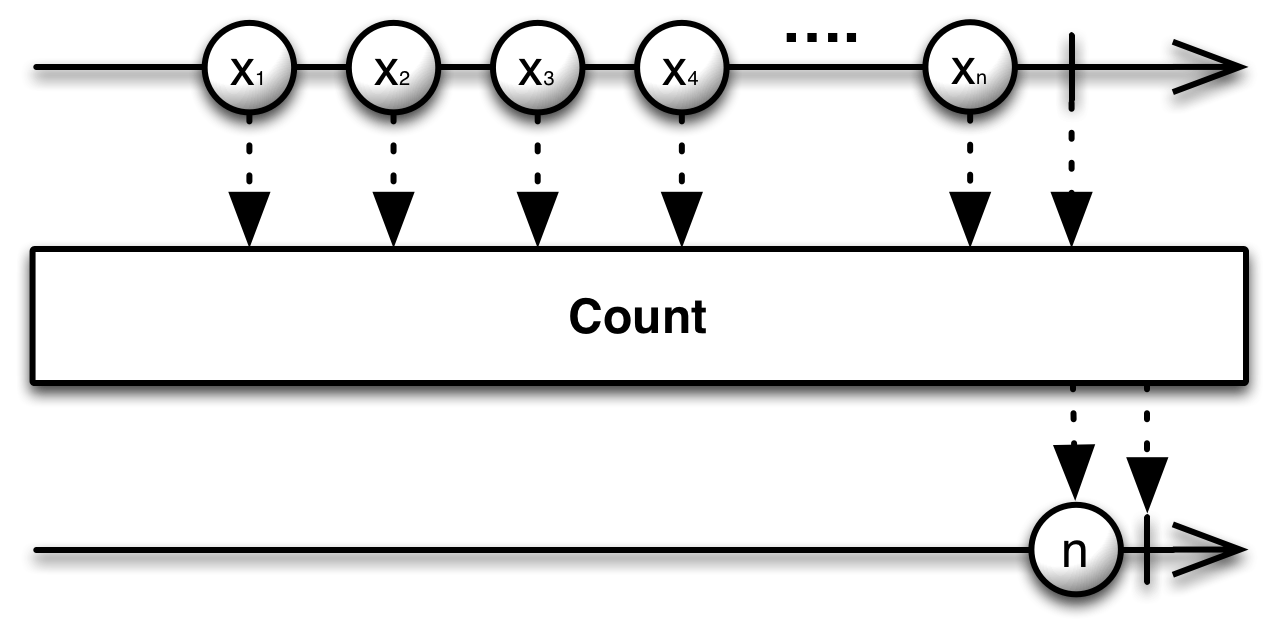

Our first method is count. It serves the same purpose as length and size, found in most Java containers. This method will return an observable that waits until the sequence completes and emits the number of values encountered.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0, 3);

values

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Values"));

values

.count()

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Count"));Values: 0

Values: 1

Values: 2

Values: Completed

Count: 3

Count: Completed

There is also countLong for sequences that may exceed the capacity of a standard integer.

first will return an observable that emits only the first value in a sequence. It is similar to take(1), except that it will emit java.util.NoSuchElementException if none is found. If you use the overload that takes a predicate, the first value that matches the predicate is returned.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

values

.first(v -> v>5)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("First"));First: 6

Instead of getting a java.util.NoSuchElementException, you can use firstOrDefault to get a default value when the sequence is empty.

last and lastOrDefault work in the same way as first, except that the item returned is the last item before the sequence completed. When using the overload with a predicate, the item returned is the last item that matched the predicate. We'll skip presenting examples, because they are trivial, but you can find them in the example code.

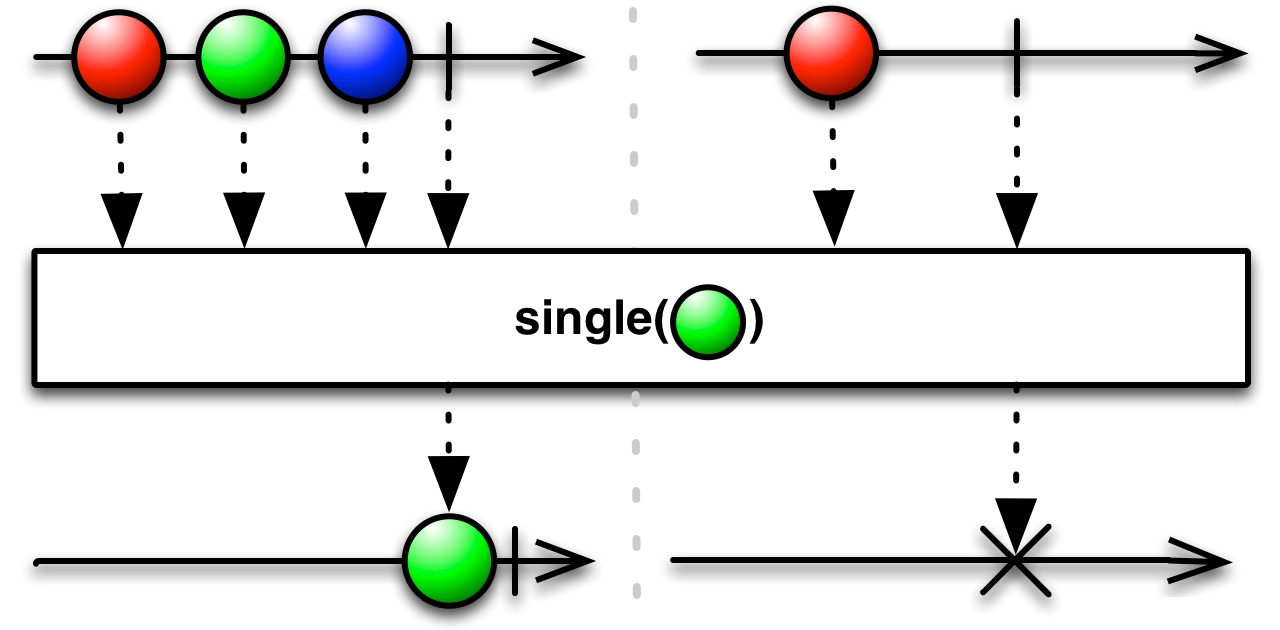

single emits the only value in the sequence, or the only value that met predicate when one is given. It differs from first and last in that it does not ignore multiple matches. If multiple matches are found, it will emit an error. It can be used to assert that a sequence must only contain one such value.

Remember that single must check the entire sequence to ensure your assertion.

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

values.take(10)

.single(v -> v == 5L) // Emits a result

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Single1"));

values

.single(v -> v == 5L) // Never emits

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Single2"));Single1: 5

Single1: Completed

Like in the previous methods, you can have a default value with singleOrDefault

The methods we saw on this chapter so far don't seem that different from the ones in previous chapters. We will now see two very powerful methods that will greatly expand what we can do with an observable. Many of the methods we've seen so far can be implemented using those.

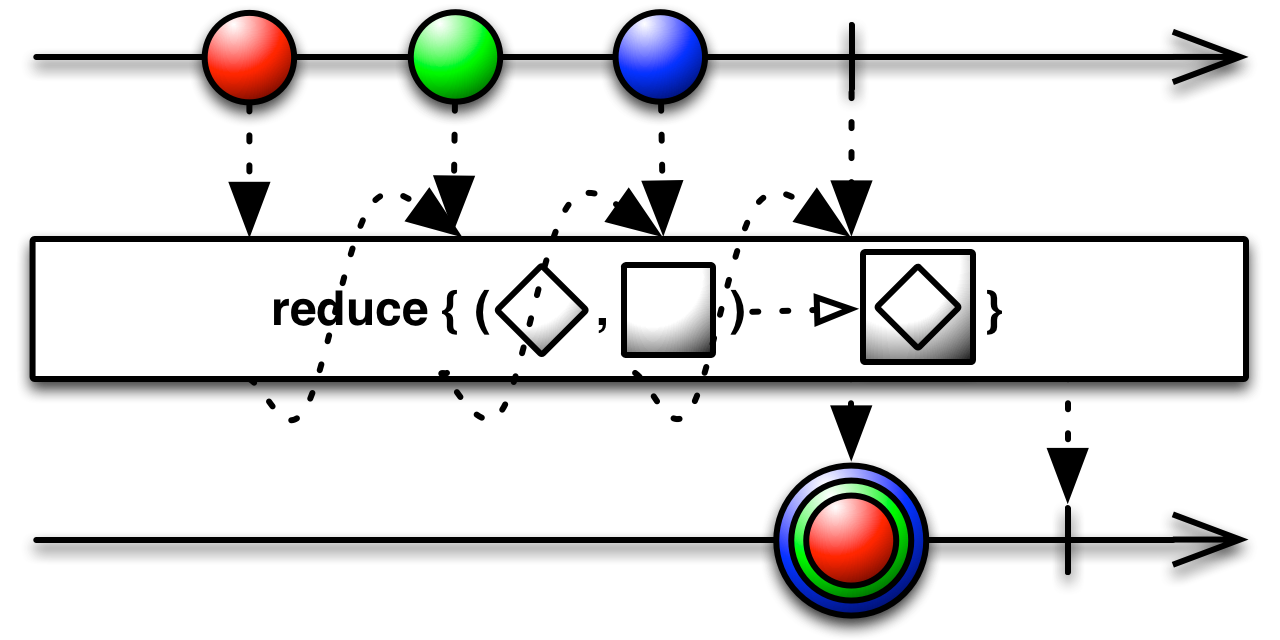

You may have heard of reduce from [MapReduce] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MapReduce). Alternatively, you might have met it under the names "aggregate", "accumulate" or "fold". The general idea is that you produce a single value out of many by combining them two at a time. In its most basic overload, all you need is a function that combines two values into one.

public final Observable<T> reduce(Func2<T,T,T> accumulator)This is best explained with an example. Here we will calculate the sum of a sequence of integers: 0+1+2+3+4+.... We will also calculate the minimum value for a different example;

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0,5);

values

.reduce((i1,i2) -> i1+i2)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Sum"));

values

.reduce((i1,i2) -> (i1>i2) ? i2 : i1)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Min"));Sum: 10

Sum: Completed

Min: 0

Min: Completed

reduce in Rx is not identical to "reduce" in parallel systems. In the context of parallel systems, it implies that the pairs of values can be choosen arbitrarily so that multiple machines can work independently. In Rx, the accumulator function is applied in sequence from left to right (as seen on the marble diagram). Each time, the accumulator function combines the result of the previous step with the next value. This is more obvious in another overload:

public final <R> Observable<R> reduce(R initialValue, Func2<R,? super T,R> accumulator)The accumulator returns a different type than the one in the observable. The first parameter for the accumulator is the previous partial result of the accumulation process and the second is the next value. To begin the process, an initial value is supplied. We will demonstrate the usefulness of this by reimplementing count

Observable<String> values = Observable.just("Rx", "is", "easy");

values

.reduce(0, (acc,next) -> acc + 1)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Count"));Count: 3

Count: Completed

We start with an accumulator of 0, as we have counted 0 items. Every time a new item arrives, we return a new accumulator that is increased by one. The last value corresponds to the number of elements in the source sequence.

reduce can be used to implement the functionality of most of the operators that emit a single value. It can not implement behaviour where a value is emitted before the source completes. So, you can implement last using reduce, but an implementation of all would not behave exactly like the original.

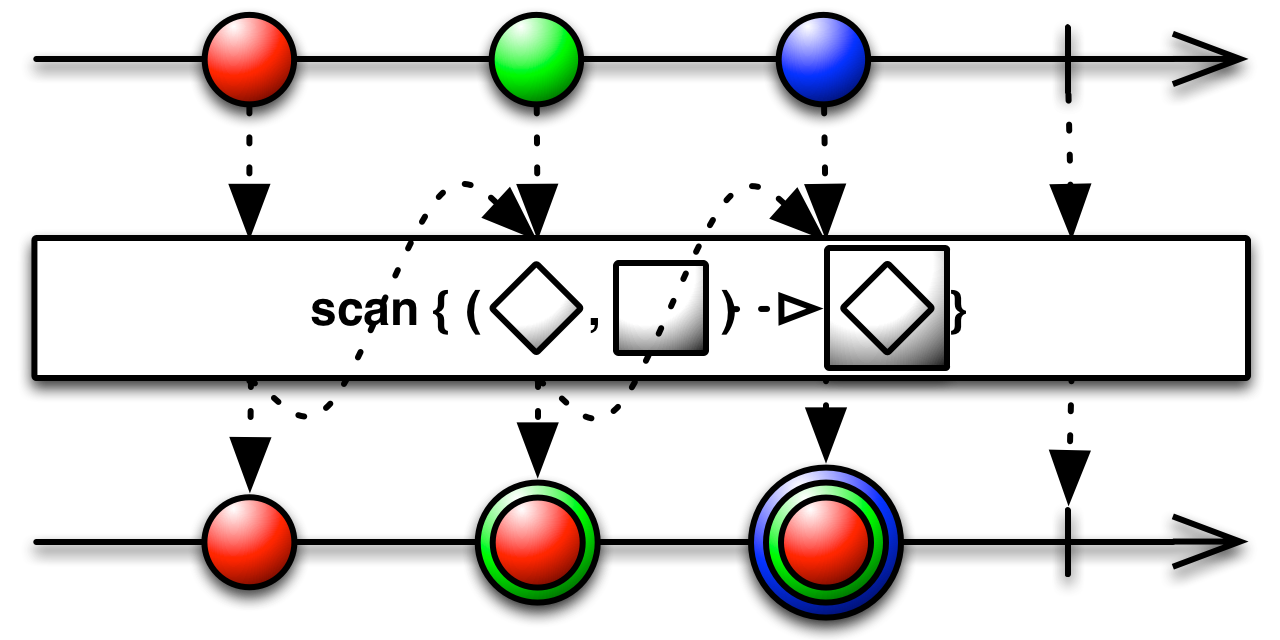

scan is very similar to reduce, with the key difference being that scan will emit all the intermediate results.

public final Observable<T> scan(Func2<T,T,T> accumulator)In the case of our example for a sum, using scan will produce a running sum.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0,5);

values

.scan((i1,i2) -> i1+i2)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Sum"));Sum: 0

Sum: 1

Sum: 3

Sum: 6

Sum: 10

Sum: Completed

scan is more general than reduce, since reduce can be implemented with scan: reduce(acc) = scan(acc).takeLast()

scan emits when the source emits and does not need the source to complete. We demonstrate that by implementing an observable that returns a running minimum:

Subject<Integer, Integer> values = ReplaySubject.create();

values

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Values"));

values

.scan((i1,i2) -> (i1<i2) ? i1 : i2)

.distinctUntilChanged()

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Min"));

values.onNext(2);

values.onNext(3);

values.onNext(1);

values.onNext(4);

values.onCompleted();Values: 2

Min: 2

Values: 3

Values: 1

Min: 1

Values: 4

Values: Completed

Min: Completed

In reduce nothing is stopping your accumulator from being a collection. You can use reduce to collect every value in Observable<T> into a List<T>.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(10,5);

values

.reduce(

new ArrayList<Integer>(),

(acc, value) -> {

acc.add(value);

return acc;

})

.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

The code above has a problem with formality: reduce is meant to be a functional fold and such folds are not supposed to work on mutable accumulators. If we were to do this the "right" way, we would have to create a new instance of ArrayList<Integer> for every new item, like this:

// Formally correct but very inefficient

.reduce(

new ArrayList<Integer>(),

(acc, value) -> {

ArrayList<Integer> newAcc = (ArrayList<Integer>) acc.clone();

newAcc.add(value);

return newAcc;

})The performance of creating a new collection for every new item is unacceptable. For that reason, Rx offers the collect operator, which does the same thing as reduce, only using a mutable accumulator this time. By using collect you document that you are not following the convention of immutability and you also simplify your code a little:

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(10,5);

values

.collect(

() -> new ArrayList<Integer>(),

(acc, value) -> acc.add(value))

.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));[10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Usually, you won't have to collect values manually. RxJava offers a variety of operators for collecting your sequence into a container. Those aggregators return an observable that will emit the corresponding collection when it is ready, just like what we did here. We will see such aggregators next.

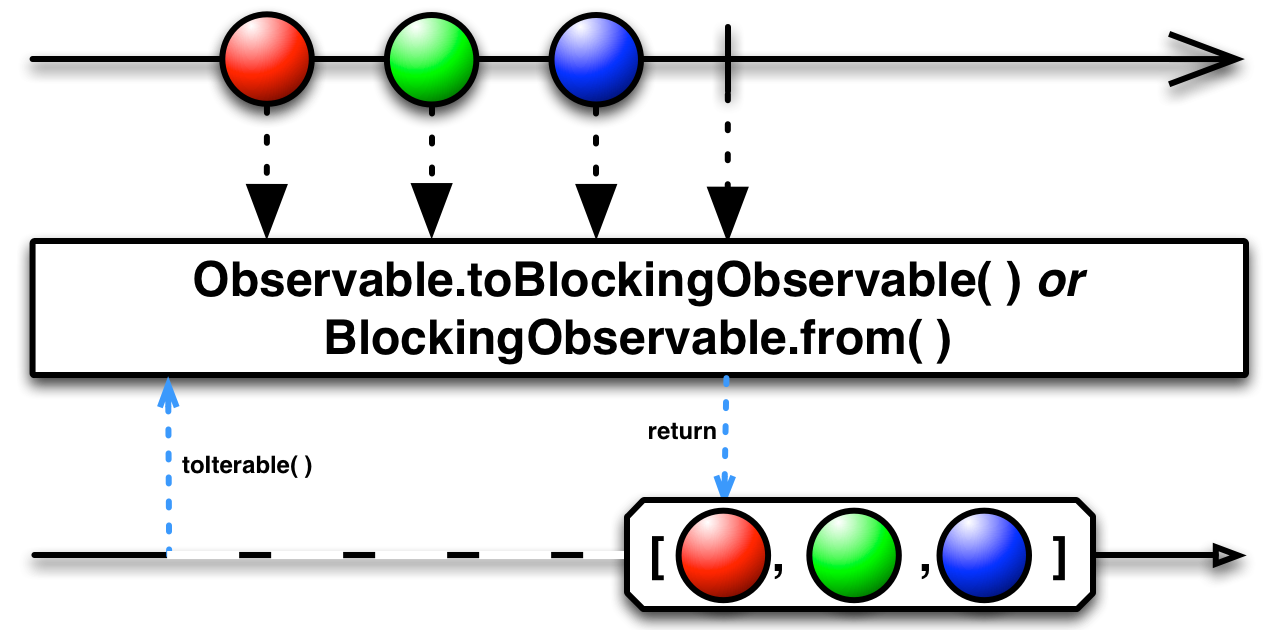

The example above could be implemented as

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(10,5);

values

.toList()

.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));The toSortedList aggregator works like toList, except that the resulting list is sorted. Here are the signatures:

public final Observable<java.util.List<T>> toSortedList()

public final Observable<java.util.List<T>> toSortedList(

Func2<? super T,? super T,java.lang.Integer> sortFunction)As we can see, we can either use the default comparison for the objects, or supply our own sorting function. The sorting function follows the semantics of Comparator's compare method.

In this example, we sort integers in reverse order with a custom sort function

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(10,5);

values

.toSortedList((i1,i2) -> i2 - i1)

.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));[14, 13, 12, 11, 10]

toMap turns our sequence of T into a Map<TKey,T>. There are 3 overloads

public final <K> Observable<java.util.Map<K,T>> toMap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector)

public final <K,V> Observable<java.util.Map<K,V>> toMap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector,

Func1<? super T,? extends V> valueSelector)

public final <K,V> Observable<java.util.Map<K,V>> toMap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector,

Func1<? super T,? extends V> valueSelector,

Func0<? extends java.util.Map<K,V>> mapFactory)keySelector is a function that produces a key from a value. valueSelector produces from the emitted value the actual value that will be stored in the map. mapFactory creates the collection that will hold the items.

Lets start with an example of the simplest overload. We want to map people to their age. First, we need a data structure to work on:

class Person {

public final String name;

public final Integer age;

public Person(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

}Observable<Person> values = Observable.just(

new Person("Will", 25),

new Person("Nick", 40),

new Person("Saul", 35)

);

values

.toMap(person -> person.name)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("toMap"));toMap: {Saul=Person@7cd84586, Nick=Person@30dae81, Will=Person@1b2c6ec2}

toMap: Completed

Now we will only use the age as a value

Observable<Person> values = Observable.just(

new Person("Will", 25),

new Person("Nick", 40),

new Person("Saul", 35)

);

values

.toMap(

person -> person.name,

person -> person.age)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("toMap"));toMap: {Saul=35, Nick=40, Will=25}

toMap: Completed

If we want to be explicit about the container that will be used or initialise it, we can supply our own container:

values

.toMap(

person -> person.name,

person -> person.age,

() -> new HashMap())

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("toMap"));The container is provided as a factory function because a new container needs to be created for every new subscription.

When mapping, it is very common that many values share the same key. The datastructure that maps one key to multiple values is called a multimap and it is a map from keys to collections. This process can also be called "grouping".

public final <K> Observable<java.util.Map<K,java.util.Collection<T>>> toMultimap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector)

public final <K,V> Observable<java.util.Map<K,java.util.Collection<V>>> toMultimap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector,

Func1<? super T,? extends V> valueSelector)

public final <K,V> Observable<java.util.Map<K,java.util.Collection<V>>> toMultimap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector,

Func1<? super T,? extends V> valueSelector,

Func0<? extends java.util.Map<K,java.util.Collection<V>>> mapFactory)

public final <K,V> Observable<java.util.Map<K,java.util.Collection<V>>> toMultimap(

Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector,

Func1<? super T,? extends V> valueSelector,

Func0<? extends java.util.Map<K,java.util.Collection<V>>> mapFactory,

Func1<? super K,? extends java.util.Collection<V>> collectionFactory)And here is an example where we group by age.

Observable<Person> values = Observable.just(

new Person("Will", 35),

new Person("Nick", 40),

new Person("Saul", 35)

);

values

.toMultimap(

person -> person.age,

person -> person.name)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("toMap"));toMap: {35=[Will, Saul], 40=[Nick]}

toMap: Completed

The first three overloads are familiar from toMap. The fourth allows us to provide not only the Map but also the Collection that the values will be stored in. The key is provided as a parameter, in case we want to customise the corresponding collection based on the key. In this example we'll just ignore it.

Observable<Person> values = Observable.just(

new Person("Will", 35),

new Person("Nick", 40),

new Person("Saul", 35)

);

values

.toMultimap(

person -> person.age,

person -> person.name,

() -> new HashMap(),

(key) -> new ArrayList())

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("toMap"));The operators just presented have actually limited use. It is tempting for a beginner to collect the data in a collection and process them in the traditional way. That should be avoided not just for didactic purposes, but because this practice defeats the advantages of using Rx in the first place.

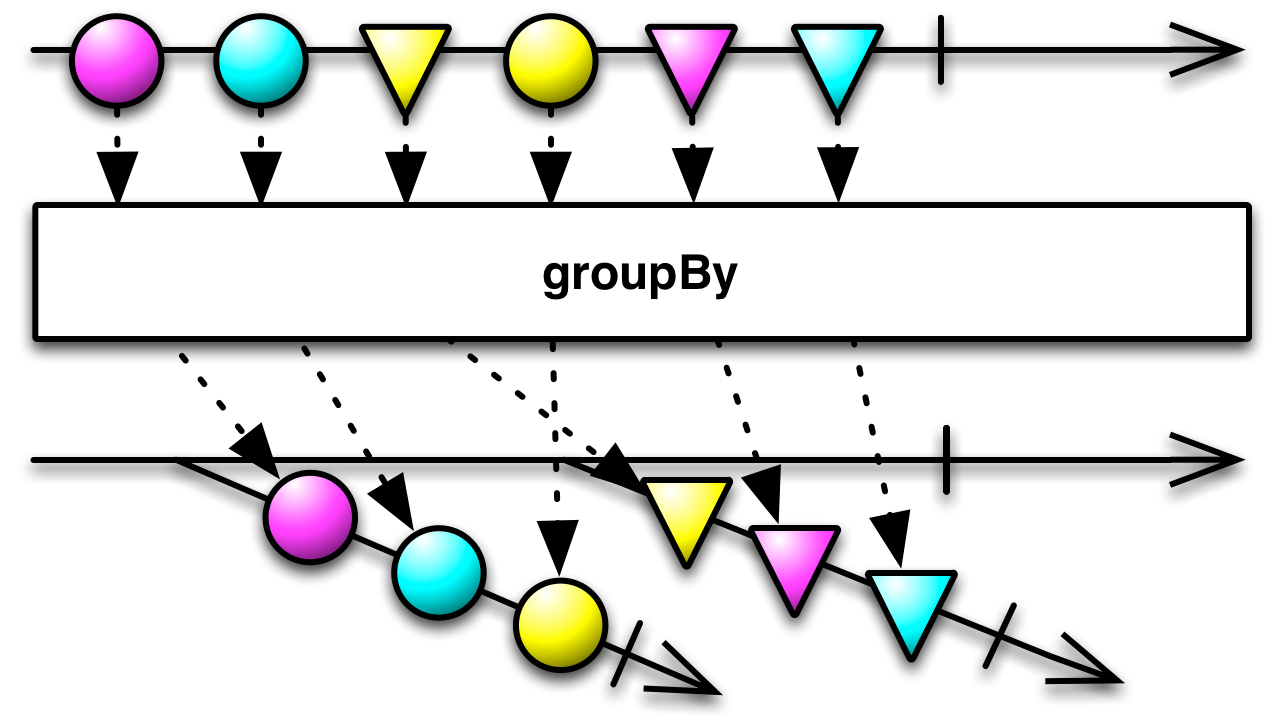

The last general function that we will see for now is groupBy. It is the Rx way of doing toMultimap. For each value, it calculates a key and groups the values into separate observables based on that key.

public final <K> Observable<GroupedObservable<K,T>> groupBy(Func1<? super T,? extends K> keySelector)The return value is an observable of GroupedObservable. Every time a new key is met, a new inner GroupedObservable will be emitted. That type is nothing more than a standard observable with a getKey() accessor, for getting the group's key. As values come from the source observable, they will be emitted by the observable with the corresponding key.

The nested observables may complicate the signature, but they offer the advantage of allowing the groups to start emitting their items before the source observable has completed.

In the next example, we will take a set of words and, for each starting letter, we will print the last word that occured.

Observable<String> values = Observable.just(

"first",

"second",

"third",

"forth",

"fifth",

"sixth"

);

values.groupBy(word -> word.charAt(0))

.subscribe(

group -> group.last()

.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(group.getKey() + ": " + v))

);The above example works, but it is a bad idea to have nested subscribes. You can do the same with

Observable<String> values = Observable.just(

"first",

"second",

"third",

"forth",

"fifth",

"sixth"

);

values.groupBy(word -> word.charAt(0))

.flatMap(group ->

group.last().map(v -> group.getKey() + ": " + v)

)

.subscribe(v -> System.out.println(v));s: sixth

t: third

f: fifth

map and flatMap are unknown for now. We will introduce them properly in the next chapter.

Nested observables may be confusing at first, but they are a powerful construct that has many uses. We borrow some nice examples, as outlined in www.introtorx.com

- Partitions of Data

- You may partition data from a single source so that it can easily be filtered and shared to many sources. Partitioning data may also be useful for aggregates as we have seen. This is commonly done with the

groupByoperator.

- You may partition data from a single source so that it can easily be filtered and shared to many sources. Partitioning data may also be useful for aggregates as we have seen. This is commonly done with the

- Online Game servers

- Consider a sequence of servers. New values represent a server coming online. The value itself is a sequence of latency values allowing the consumer to see real time information of quantity and quality of servers available. If a server went down then the inner sequence can signal that by completing.

- Financial data streams

- New markets or instruments may open and close during the day. These would then stream price information and could complete when the market closes.

- Chat Room

- Users can join a chat (outer sequence), leave messages (inner sequence) and leave a chat (completing the inner sequence).

- File watcher

- As files are added to a directory they could be watched for modifications (outer sequence). The inner sequence could represent changes to the file, and completing an inner sequence could represent deleting the file.

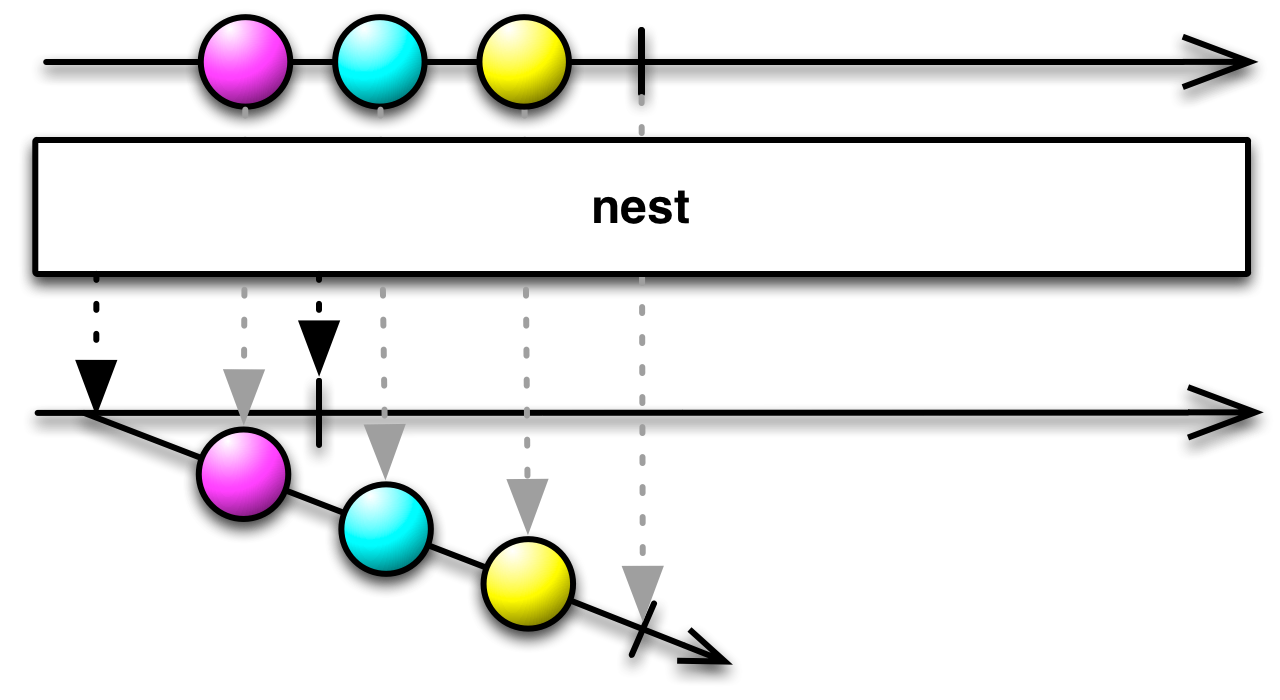

When dealing with nested observables, the nest operator becomes useful. It allows you to turn a non-nested observable into a nested one. nest takes a source observable and returns an observable that will emit the source observable and then terminate.

Observable.range(0, 3)

.nest()

.subscribe(ob -> ob.subscribe(System.out::println));0

1

2

Nesting observables to consume them doesn't make much sense. Towards the end of the pipeline, you'd rather flatten and simplify your observables, rather than nest them. Nesting is useful when you need to make a non-nested observable be of the same type as a nested observable that you have from elsewhere. Once they are of the same type, you can combine them, as we will see in the chapter about [combining sequences](/Part 3 - Taming the sequence/4. Combining sequences.md).

In this chapter we will see ways of changing the format of the data. In the real world, an observable may be of any type. It is uncommon that the data is already in format that we want them in. More likely, the values need to be expanded, trimmed, evaluated or simply replaced with something else.

This will complete the three basic categories of operations. map and flatMap are the fundamental methods in the third category. In literature, you will often find them refered to as "bind", for reasons that are beyond the scope of this guide.

- Ana(morphism)

T-->IObservable<T> - Cata(morphism)

IObservable<T>-->T - Bind

IObservable<T1>-->IObservable<T2>

In the last chapter we introduced an implementation of Subscriber for convenience. We will continue to use it in the examples of this chapter.

class PrintSubscriber extends Subscriber{

private final String name;

public PrintSubscriber(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

@Override

public void onCompleted() {

System.out.println(name + ": Completed");

}

@Override

public void onError(Throwable e) {

System.out.println(name + ": Error: " + e);

}

@Override

public void onNext(Object v) {

System.out.println(name + ": " + v);

}

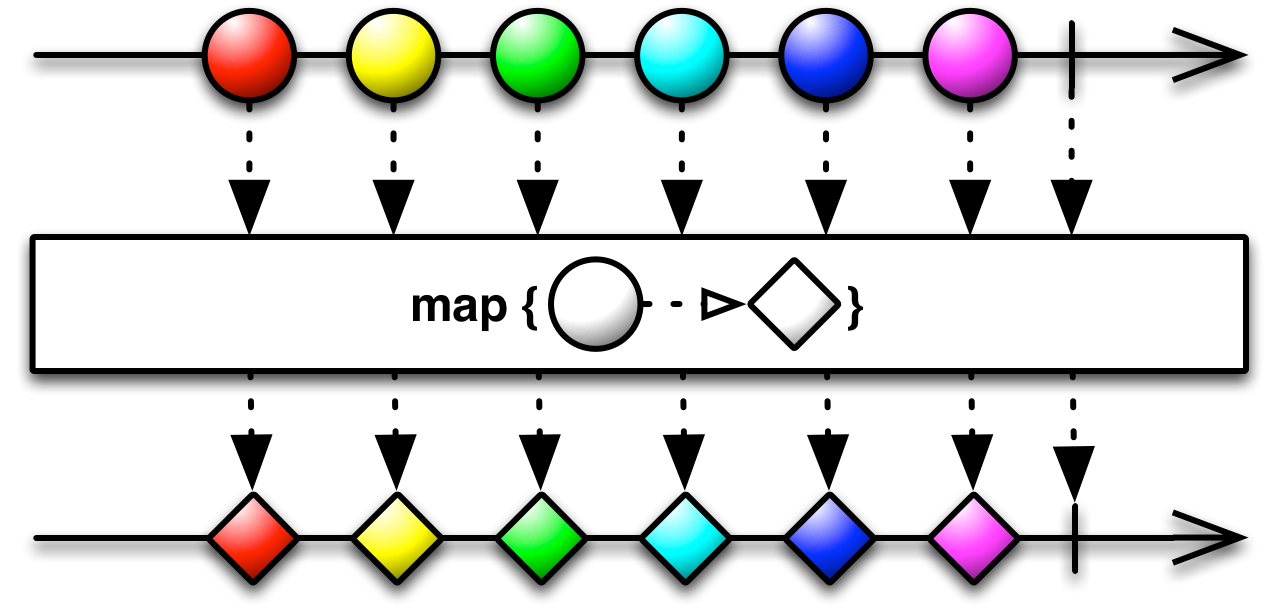

}The basic method for transformation is map (also known as "select" in SQL-inspired systems like LINQ). It takes a transformation function which takes an item and returns a new item of any type. The returned observable is composed of the values returned by the transformation function.

public final <R> Observable<R> map(Func1<? super T,? extends R> func)In the first example, we will take a sequence of integers and increase them by 3

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(0,4);

values

.map(i -> i + 3)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Map"));Map: 3

Map: 4

Map: 5

Map: 6

Map: Completed

This was something we could do without map, for example by using Observable.range(3,4). In the following, we will do something more practical. The producer will emit numeric values as a string, like many UIs often do, and then use map to convert them to a more processable integer format.

Observable<Integer> values =

Observable.just("0", "1", "2", "3")

.map(Integer::parseInt);

values.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Map"));Map: 0

Map: 1

Map: 2

Map: 3

Map: Completed

This transformation is simple enough that we could also do it on the subscriber's side, but that would be a bad division of responsibilities. When developing the side of the producer, you want to present things in the neatest and most convenient way possible. You wouldn't dump the raw data and let the consumer figure it out. In our example, since we said that the API produces integers, it should do just that. Tranfomation operators allow us to convert the initial sequences into the API that we want to expose.

cast is a shorthand for the transformation of casting the items to a different type. If you had an Observable<Object> that you knew would only only emit values of type T, then it is just simpler to cast the observable, rather than do the casting in your lambda functions.

Observable<Object> values = Observable.just(0, 1, 2, 3);

values

.cast(Integer.class)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Map"));Map: 0

Map: 1

Map: 2

Map: 3

Map: Completed

The cast method will fail if not all of the items can be cast to the specified type.

Observable<Object> values = Observable.just(0, 1, 2, "3");

values

.cast(Integer.class)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Map"));Map: 0

Map: 1

Map: 2

Map: Error: java.lang.ClassCastException: Cannot cast java.lang.String to java.lang.Integer

If you would rather have such cases ignored, you can use the ofType method. This will filter our items that cannot be cast and then cast the sequence to the desired type.

Observable<Object> values = Observable.just(0, 1, "2", 3);

values

.ofType(Integer.class)

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Map"));Map: 0

Map: 1

Map: 3

Map: Completed

The timestamp and timeInterval methods enable us to enrich our values with information about the asynchronous nature of sequences. timestamp transforms values into the Timestamped<T> type, which contains the original value, along with a timestamp for when the event was emitted.

public final Observable<Timestamped<T>> timestamp()Here's an example:

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

values.take(3)

.timestamp()

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Timestamp"));Timestamp: Timestamped(timestampMillis = 1428611094943, value = 0)

Timestamp: Timestamped(timestampMillis = 1428611095037, value = 1)

Timestamp: Timestamped(timestampMillis = 1428611095136, value = 2)

Timestamp: Completed

The timestamp allows us to see that the items were emitted roughly 100ms apart (Java offers few guarantees on that).

If we are more interested in how much time has passed since the last item, rather than the absolute moment in time when the items were emitted, we can use the timeInterval method.

public final Observable<TimeInterval<T>> timeInterval()Using timeInterval in the same sequence as before:

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

values.take(3)

.timeInterval()

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("TimeInterval"));TimeInterval: TimeInterval [intervalInMilliseconds=131, value=0]

TimeInterval: TimeInterval [intervalInMilliseconds=75, value=1]

TimeInterval: TimeInterval [intervalInMilliseconds=100, value=2]

TimeInterval: Completed

The information captured by timestamp and timeInterval is very useful for logging and debugging. It is Rx's way of acquiring information about the asynchronicity of sequences.

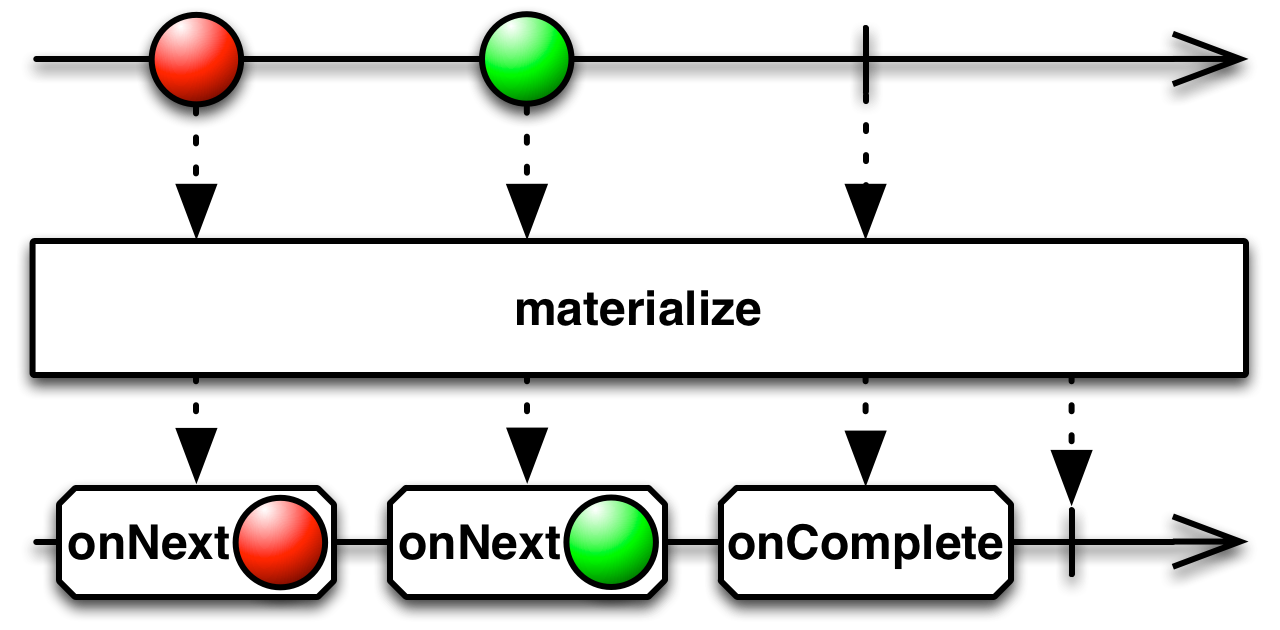

Also useful for logging is materialize. materialize transforms a sequence into its metadata representation.

public final Observable<Notification<T>> materialize()The notification type can represent any event, i.e. the emission of a value, an error or completion. Notice in the marble diagram above that the emission of "onCompleted" did not mean the end of the sequence, as the sequence actually ends afterwards. Here's an example

Observable<Long> values = Observable.interval(100, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

values.take(3)

.materialize()

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("Materialize"));Materialize: [rx.Notification@a4c802e9 OnNext 0]

Materialize: [rx.Notification@a4c802ea OnNext 1]

Materialize: [rx.Notification@a4c802eb OnNext 2]

Materialize: [rx.Notification@18d48ace OnCompleted]

Materialize: Completed

The Notification type contains methods for determining the type of the event as well the carried value or Throwable, if any.

dematerialize will reverse the effect of materialize, returning a materialized observable to its normal form.

map took one value and returned another, replacing items in the sequence one-for-one. flatMap will replace an item with any number of items, including zero or infinite items. flatMap's transformation method takes values from the source observable and, for each of them, returns a new observable that emits the new values.

public final <R> Observable<R> flatMap(Func1<? super T,? extends Observable<? extends R>> func)The observable returned by flatMap will emit all the values emitted by all the observables produced by the transformation function. Values from the same observable will be in order, but they may be interleaved with values from other observables.

Let's start with a simple example, where flatMap is applied on an observable with a single value. values will emit a single value, 2. flatMap will turn it into an observable that is the range between 0 and 2. The values in this observable are emitted in the final observable.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.just(2);

values

.flatMap(i -> Observable.range(0,i))

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("flatMap"));flatMap: 0

flatMap: 1

flatMap: Completed

When flatMap is applied on an observable with multiple values, each value will produce a new observable. values will emit 1, 2 and 3. The resulting observables will emit the values [0], [0,1] and [0,1,2], respectively. The values will be flattened together into one observable: the one that is returned by flatMap.

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.range(1,3);

values

.flatMap(i -> Observable.range(0,i))

.subscribe(new PrintSubscriber("flatMap"));flatMap: 0

flatMap: 0

flatMap: 1

flatMap: 0

flatMap: 1

flatMap: 2

flatMap: Completed

Much like map, flatMap's input and output type are free to differ. In the next example, we will transform integers into Character

Observable<Integer> values = Observable.just(1);

values

.flatMap(i ->

Observable.just(

Character.valueOf((char)(i+64))

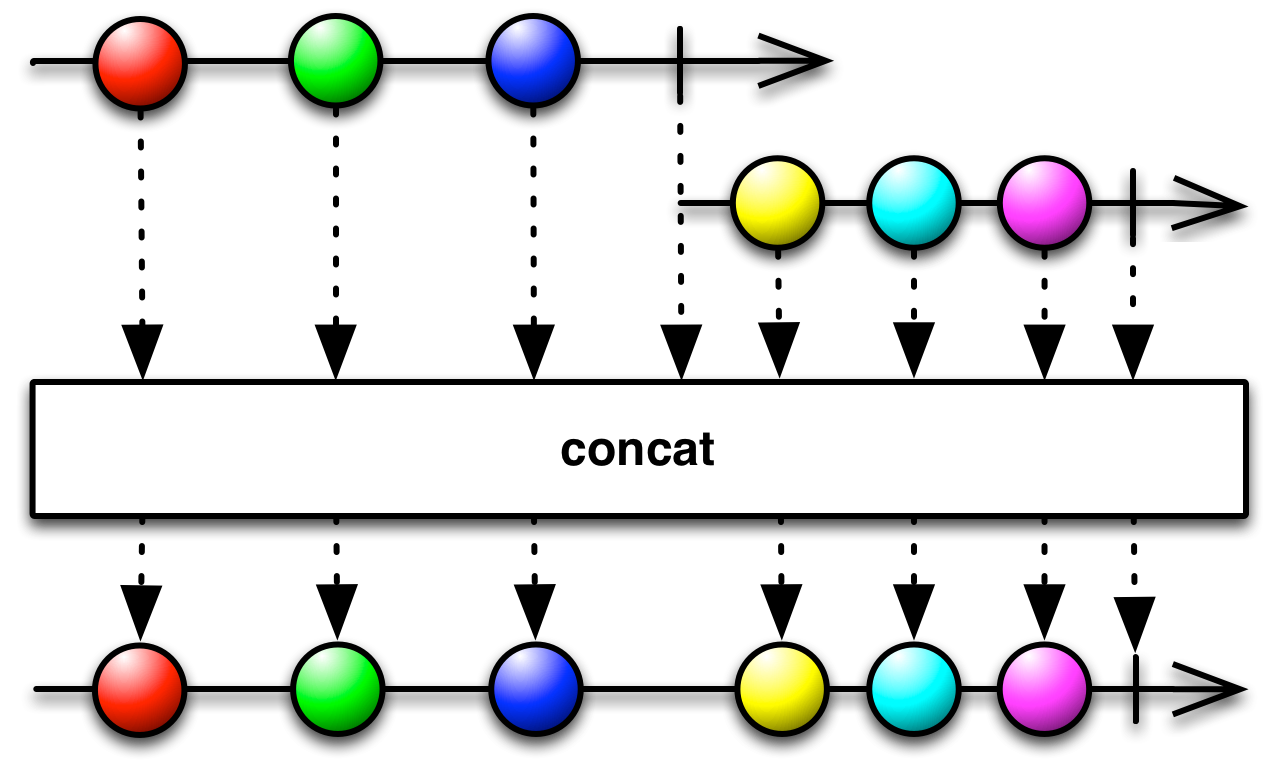

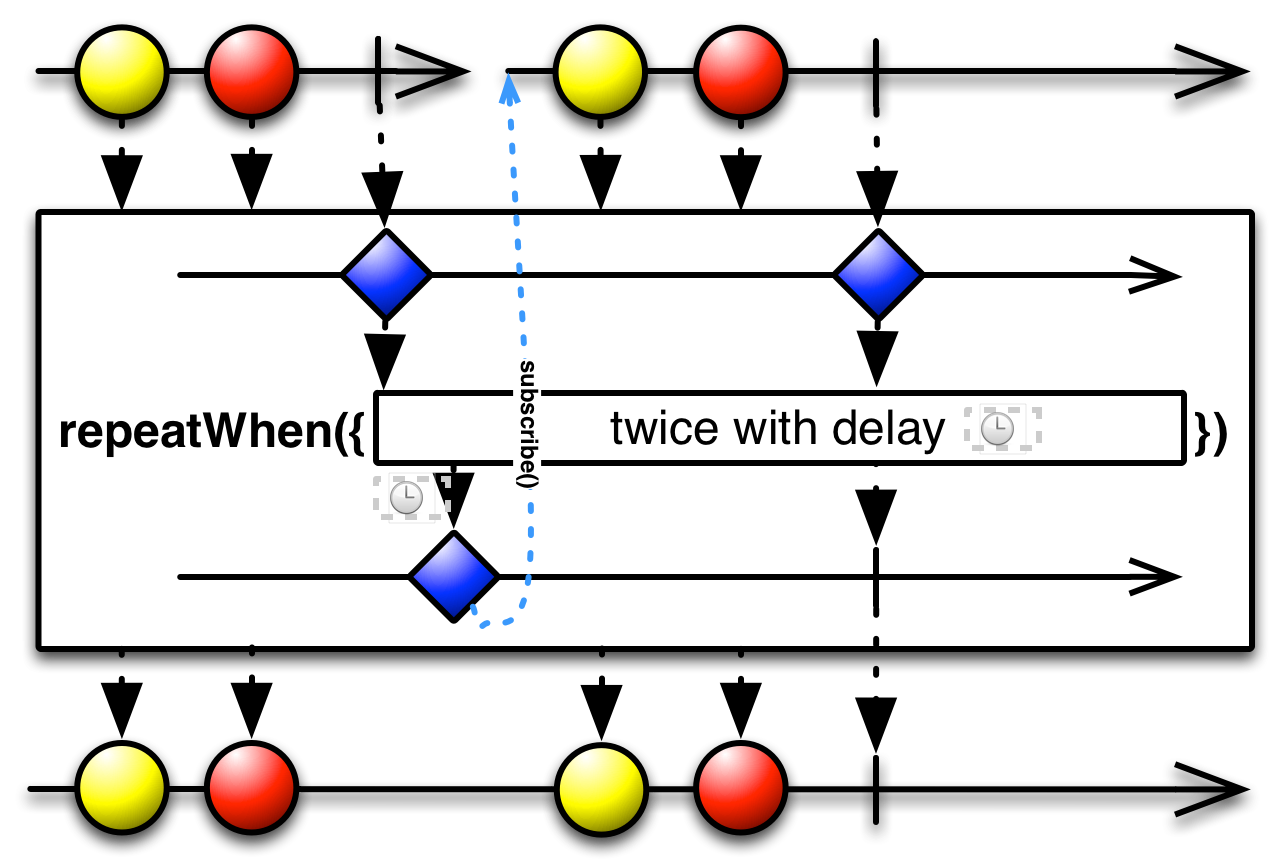

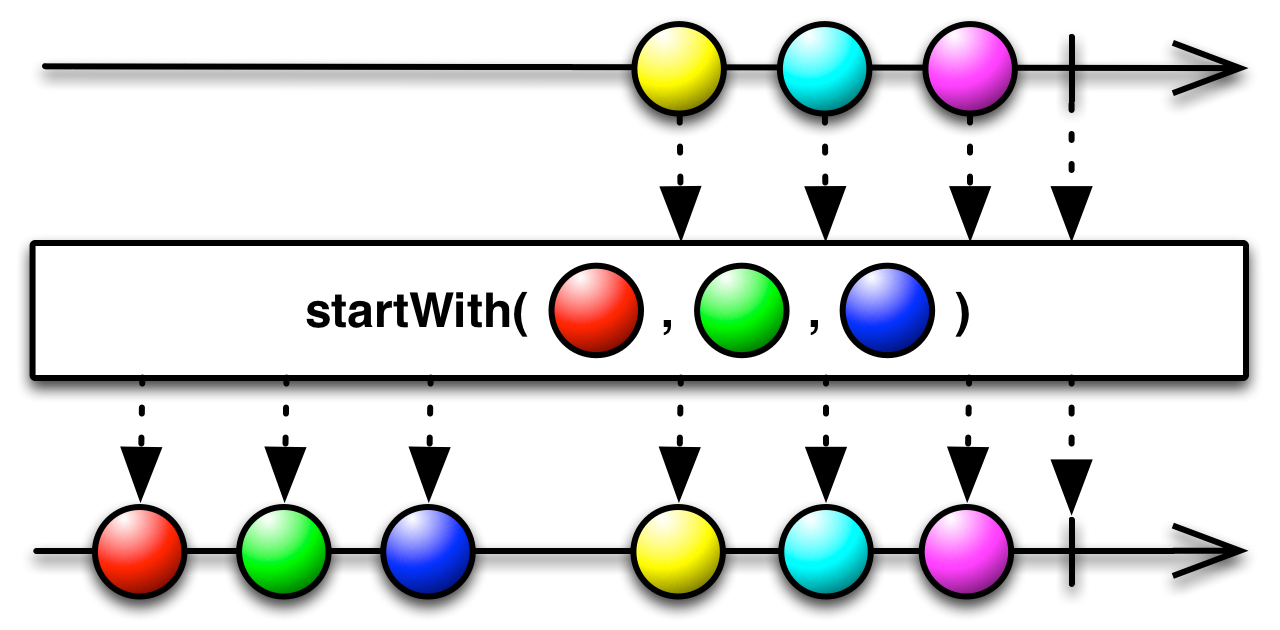

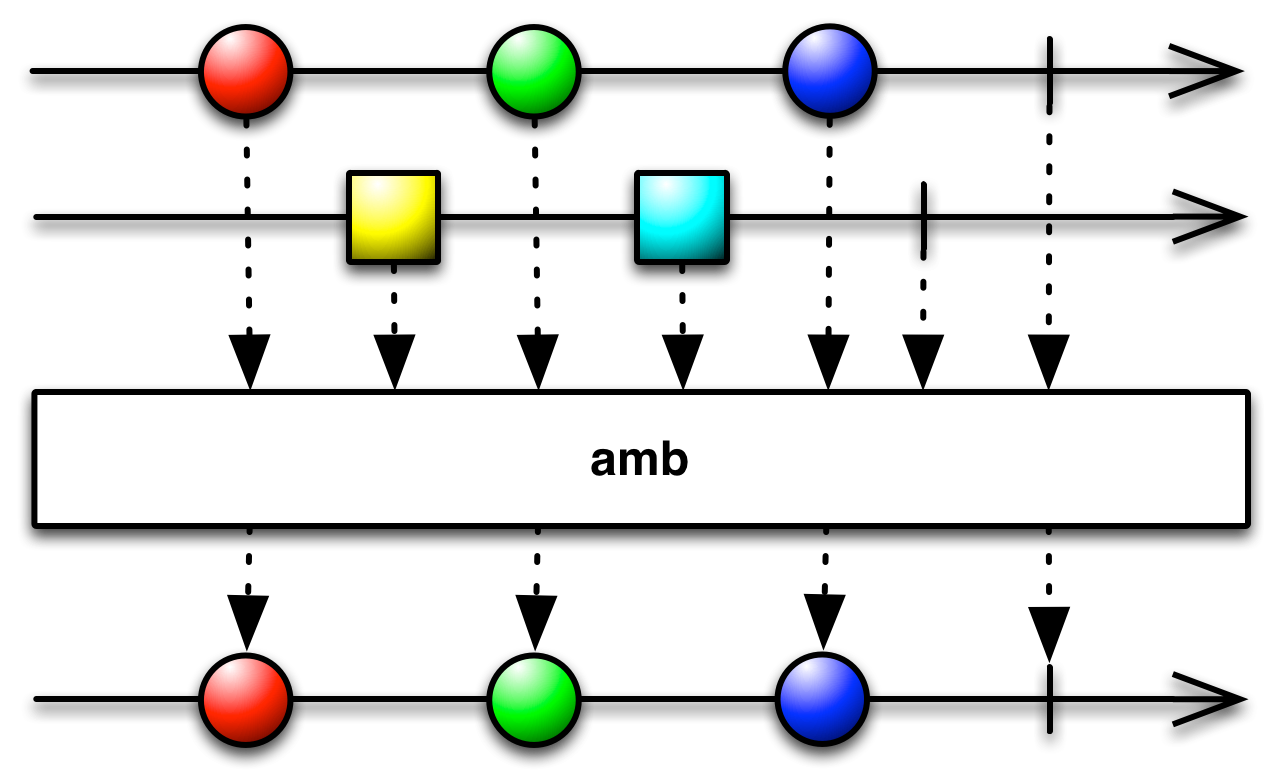

))