Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are physical contacts between two or more proteins and are typically essential for carrying out normal protein functions in the cell. Variation in genetic coding sequences can result in missense mutations in protein amino acid sequence, potentially disrupting PPIs and hindering or destroying normal protein function. As such, reliably predicting how a missense mutation will affect an interaction between two proteins could is an interesting deep learning task to understand protein behavior better and to differentiate benign and pathogenic mutations. There have been multiple high-accuracy deep learning models released for PPI prediction. However, I found that these models perform poorly when predicting mutant PPI effects. This performance decrease may be due to limited PPI dataset sizes or indicate that alternative protein sequence input representations are needed for model training. For this project, I attempted to create a large high-quality dataset for use in further PPI modeling attempts to improve mutant PPI prediction and to evaluate two pretrained NLP protein embedding models from the Tasks Assessing Protein Embedding (TAPE) benchmark (Rao et al., 2019) for use in binary PPI predictions.

Variation in coding sequence (CDS) regions can significantly impact protein function and potentially disrupt PPIs. Recent work by (Fragoza et al., 2019) using the ExAC dataset of CDS variants from over 60K human exomes has estimated that 10.5% of an individual's missense mutations disrupt PPIs and indicated that most PPI disrupting variants do not affect overall protein stability but instead affect specific PPI interfaces by local structural disruptions. Additionally, it has been shown that two-thirds of known pathogenic variants disrupt PPIs, with most of these disrupting only subsets of normal protein interaction profiles (Navío et al., 2019). Learning to reliably predict how small protein sequence changes can disrupt specific PPIs becomes an important step in identifying putative pathogenic variants and understanding how wild type protein interaction profiles can be disrupted through protein design efforts.

Several groups have developed predictive models that integrate protein structure information with information about measured protein-protein interactions (PPIs) to assess the likely impact of a variant (Engin, Kreisberg and Carter, 2016; Zhou et al., 2020), and multiple sequence only PPI binary predictors exist (M. Chen et al., 2019). However, these models still have limited predictive power on protein families not seen during training, mainly due to limited training data and difficulties learning the complex sequence-structure relationships necessary for interaction predictions. Larger datasets for training may help with this issue and help identify suitable representations for PPI deep learning tasks.

The prediction of PPI occurrence is a widely attempted deep learning task, with recent high accuracy and precision models adapting natural language processing (NLP) methods for protein sequence representations (M. Chen et al., 2019; Nambiar et al., 2020). Networks have also been trained to predict interaction type, binding affinity, and interaction sites from hand-picked features, sequence, and crystal structures (Geng et al., 2019; M. Chen et al., 2019; Gainza et al., 2020).

The best performing binary PPI prediction model to date is PIPR from (Chen et al., 2020), a deep residual recurrent siamese CNN. This network embeds protein sequences using amino-acid co-occurrence similarity and a one-hot encoded amino acid sequence. The embedded sequences are fed into the siamese residual RCNN portion with shared parameters to create a sequence embedding vector for each potentially interacting sequence. These vectors are combined with element-wise multiplication before being fed through a linear network portion for interaction prediction. Another state-of-the-art PPI property predictor model is MuPIPR, which predicts binding affinity change between a wild type protein pair and a mutant protein pair and uses a pre-trained bidirectional language model (BiLM) to embed all four protein input sequences to be fed into the siamese network and a residual CNN (Zhou et al., 2020). Therefore, the use of NLP models for PPI prediction is well-established.

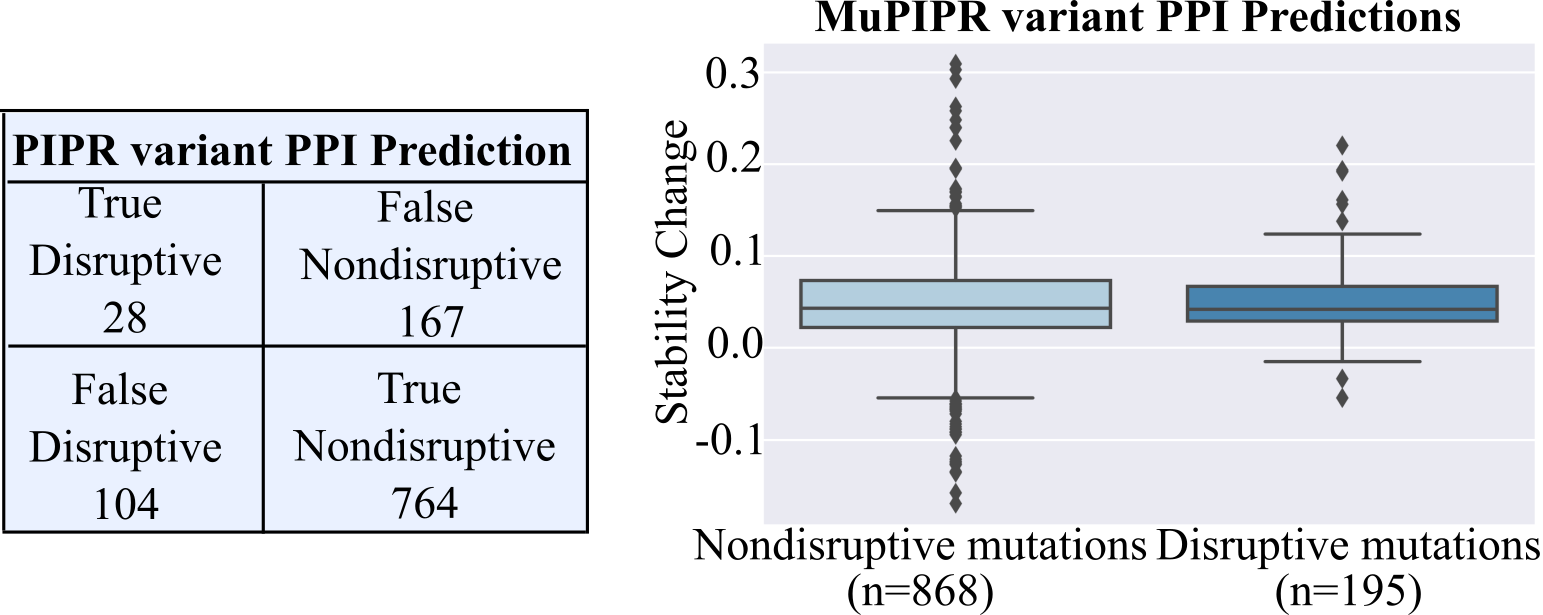

A dataset that can be used to judge the effectiveness of these state-of-the-art models for predicting how protein sequence changes can disrupt specific PPIs was recently collected by (Fragoza et al., 2019). Interaction profiles for 4797 SNV-interaction pairs were measured using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays, a common PPI measurement method that uses modified yeast to detect if two proteins interact. A subset of this dataset can be used to evaluate PIPR and MuPIPR's ability to predict mutant PPIs, as shown in Figure 1. As can be seen, these models fail to separate PPI disruptive mutants from non-disruptive mutants in the Fragoza dataset. Therefore, while these models are highly accurate on their training sets, they fail to generalize well to fine-grained sequence predictions, and a better representation or network structure is needed for binary PPI predictions.

Figure 1. PIPR and MuPIPR performance on a set of PPI disruptive and nondisrutpive mutants. True disruptive are mutants which did disrupt a PPI, and were correctly predicted as non-interacting proteins by PIPR (Chen et al., 2020), True Nondisruptive are mutants which did not disrupt a PPI and the sequences were predicted to still interact by PIPR, etc. Note that the majority of disruptive mutants are misclassified as False Nondisruptive. For MuPIPR, the Nondisruptive mutants and disrputive mutants would be expected to have differnet effects on complex stability, with disruptive mutations resulting in a much higher stability change value than nondisruptive (Zhou et al., 2020). Therefore, MuPIPR does not seem to predict these interaction pairs correctly.

Recently, an attempt was made to standardize and evaluate the effectiveness of unsupervised and semi-supervised learning techniques on several protein biology deep learning tasks, Tasks Assessing Protein Embeddings (TAPE) (Rao et al., 2019). TAPE found that semi-supervised NLP pretraining methods helped improve performance on most of the tasks tested and assessed a transformer, LSTM, ResNet, and a multiplicative LSTM (mLSTM) for protein structure, evolutionary, and engineering prediction tasks. However, there was no best performing pretrained NLP method across all assessed tasks. Two of the semi-supervised protein sequence models were made publicly available from TAPE, bert_base, a transformer, and UniRep, an mLSTM. As these are different from the NLP methods employed in PIPR and MuPIPR, they could potentially improve PPI prediction abilities (Chen et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020).

PIPR was cloned from seq_ppi, and all Fragoza dataset interactions where both partners had a maximum length of <= 600 amino acids were evaluated. Code to reproduce the PIPR portion of Figure 1 is located in currentModelFragozaComparisons/PIPR/. MuPIPR was cloned from MuPIPR, and again all Fragoza dataset interactions where both partners had a maximum length of <= 600 amino acids were evaluated. Code to reproduce the MuPIPR portion of Figure 1 is located in currentModelFragozaComparisons/MuPIPR/. (Interactions where both partners had a maximum length of <= 600 amino acids were used in this evaluation as it was the maximum input length possible between the two models).

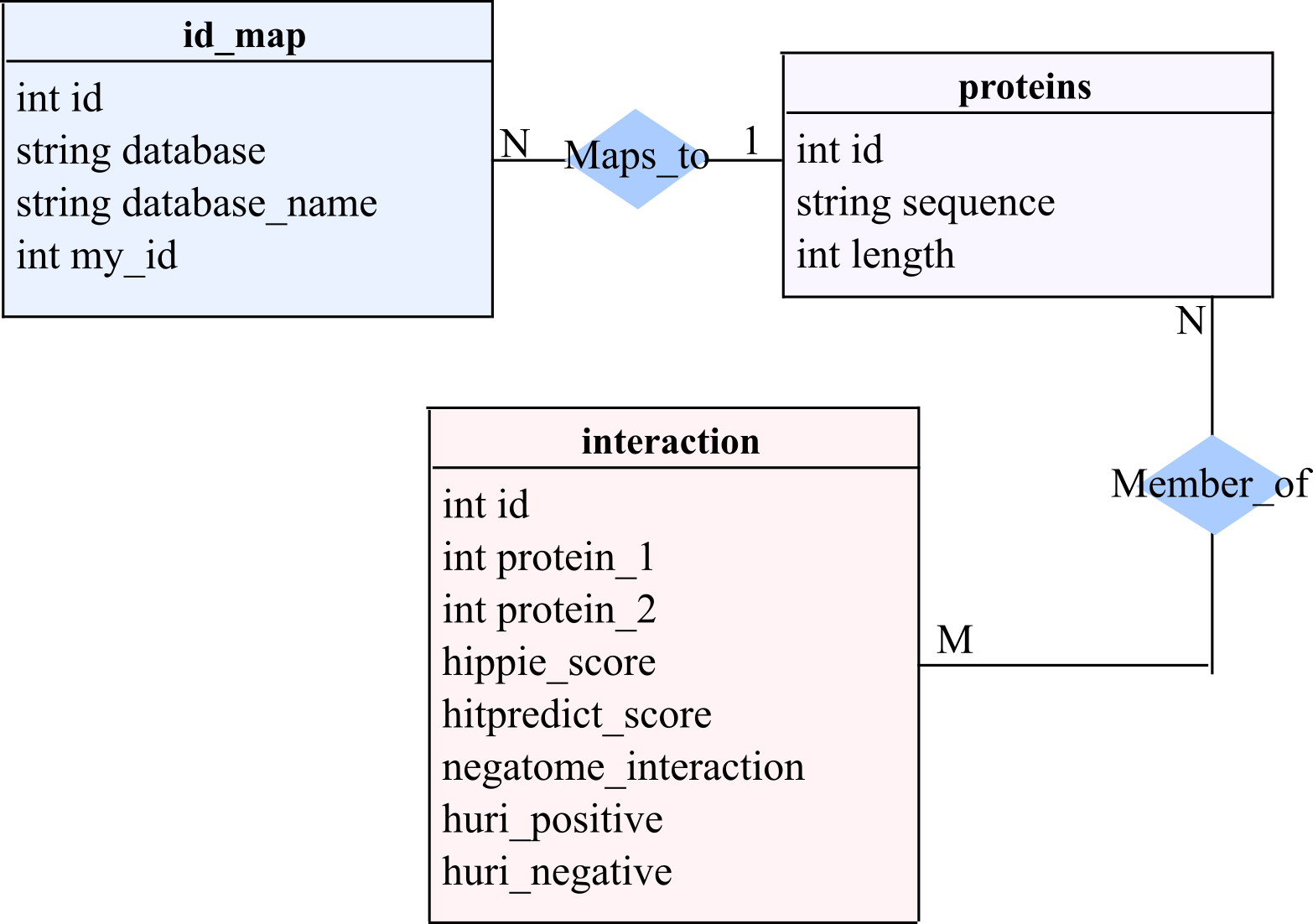

A SQL database of non-redundant PPIs, ppiDB, was constructed by combining several human PPI databases and high-throughput datasets. A simplified entity-relationship diagram of the database is shown in Figure 2. Datasets were downloaded from their respective websites, and gene IDs, transcript IDs, or Uniprot IDs were used to retrieve available sequences with the Uniprot Retrieve/ID mapping tool. Subsets of ENSEMBL sequences were manually downloaded as needed if a specific transcript ID was provided in the gathered datasets. Deleted and deprecated sequences from Uniprot were not retrieved to be incorporated into ppiDB. The databases and datasets incorporated were:

- The Human Reference Interactome (HuRI): (Luck et al., 2020) A high-throughput human PPI dataset, part of an ongoing attempt to generate a complete draft of the human interactome. It was used as a source of positive interactions (those in the dataset) and negative interactions (interactions that were screened in the all-by-all Y2H experiments, but an interaction was not detected).

- Human Integrated Protein-Protein Interaction Reference (HIPPIE) v2.2: (Alanis-Lobato et al., 2017) A confidence scored and functionally annotated human PPIs database. Used as a source of positive interactions.

- HitPredict v4: (Lopez et al., 2015) A annotated and scored database of PPIs with sources from several data repositories. Used as a source of positive interactions.

- Negatome 2.0: (Blohm et al., 2014) A database of protein pairs deemed unlikely to interact, either curated from the literature or determined from protein structures. Used as a source of negative interactions.

Figure 2. Entity Relationship diagram for the SQL database ppiDB.

Figure 2. Entity Relationship diagram for the SQL database ppiDB.

The pretrained TAPE embeddings were originally trained on sequences with a maximum length of 2000 amino acids. Therefore, to test using ppiDB for the TAPE embeddings, all sequences with length <= 2000 amino acids were extracted from ppiDB and placed in a fasta file. They were clustered at a 70% sequence identity cutoff with CD-HIT (Limin et al., 2012), a common technique in biology deep learning models to prevent leaks between training and evaluation datasets due to the high level of similarity between protein sequences, resulting in 16,614 representative cluster sequences. Positive interactions from HuRI, HIPPIE, and HitPredict were gathered from ppiDB between cluster representatives and Negatome negatives resulting in 279,775 positive interactions and 918 negative interactions between the cluster sequences. An equal number of negative interactions were then added to ppiDB from non-interacting pairs in HuRI to create a balanced dataset for network training, resulting in a total dataset of 279,775 positive interactions and 279,775 negative interactions.

Following cluster sequence selection, pre-trained unsupervised models UniRep and bert-base from TAPE were used to process cluster sequences. To replicate the CD-HIT cluster dataset embeddings exactly, install tape and use:

tape-embed unirep ppiDB.fasta ppiDB.npz babbler-1900 --tokenizer unirep --batch_size = 10. Bert-base was processed in runBert.ipynb above.

As the most interesting case in PPI prediction is how well the model performs on predicting pairs that are highly dissimilar from the training set, two different versions of a train/validation/test split were conducted. In one, a fraction of dataset proteins were chosen to be part of a held-out set from training from the cluster proteins, resulting in interactions split into three groups of interactions: a group where both proteins in the interaction were seen during training, a group where only a single protein in the pairs was seen during training, and a group of pairs where both proteins were unseen during training. In the other, training, validation, and test set pairs were uniform randomly selected from the dataset.

As this project's primary goal was to create the ppiDB for future embedding attempts and to investigate the initial effectiveness of the pre-trained TAPE embedding methods, minimal network or hyperparameter exploration was completed. Simple feedforward networks were trained for a small number of iterations to determine if any loss decreases would occur in the initial epochs. Both representation methods tested used the same simple network structure of the TAPE representations of interaction proteins fed into a 300 neuron fully connected layer followed by a 100 neuron fully connected layer with a Relu activation, followed by a single neuron with binary cross-entropy loss. All bert_base models were trained for five epochs with a batch size of 32, using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. The UniRep models were trained for three epochs with a batch size of 32, using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001.

Three methods of combining the interaction protein partners were used: the concatenation of the two input sequence representations, element-wise multiplication of the input representations, and difference of the input representations.

The created database, ppiDB, is nearly an order of magnitude larger than the datasets used in training models such as PIPR and MuPIPR (Chen et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020) and can be a resource moving forward with testing new protein sequence representation methods to improve PPI prediction. It contains 22,561 protein sequences participating in 477,278 experimentally supported human PPIs. This is a stark increase compared to the benchmark datasets typically used in the literature for binary PPI prediction. The largest PPI training dataset used in PIPR contains 11,529 proteins participating in 32,959 positive interactions and 32,959 negative interactions.

All six model structures performed very poorly and had close to random performance in accuracy, as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Bert-base Model Performance

| Join method | Loss Bert-Base 3-way | Accuracy Bert-Base 3-way | Loss Bert-Base Random Split | Accuracy Bert-Base Random Split |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concatenation | 0.706 | 47.9% | 0.517 | 47.4% |

| Element-wise multiplication | 0.609 | 39.5% | 0.5100 | 46.1% |

| Subtraction | 0.663 | 37.4% | 0.433 | 47.2% |

Table 2. UniRep Model Performance

| Join method | Loss UniRep 3-way | Accuracy UniRep 3-way | Loss UniRep Random Split | Accuracy UniRep Random Split |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concatenation | 0.714 | 39.6% | 0.464 | 47.7% |

| Element-wise multiplication | 3.21 | 15.6% | 8.09 | 25.6% |

| Subtraction | 0.732 | 34.6% | 0.440 | 46.4% |

This project's main goal was to create a database that could be used in further PPI model and representation investigations, which was successfully completed. Preliminary uses of ppiDB showed that the pretrained UniRep and Bert embeddings are likely to be unsuitable for improving binary PPI prediction and unlikely to result in improved mutant PPI prediction abilities and demonstrate how to filter the database using sequence identity thresholding to create model training sets. It is surprising as these two semi-supervised methods proved unsuitable for the task, as they performed admirably in TAPE on learning tasks that required representation of protein structural information (Rao et al., 2019). However, the simple models and short training epochs used may have proved unsuitable for the task. At the very least, the database is assembled and can easily be added on to as new PPI datasets become available. While not tested here due to the failure of the bert-base and UniRep models tested, the Fragoza set was also prepared for use as a test-set for future network structures and representation method experiments.

Alanis-Lobato, G., Andrade-Navarro, M. A. and Schaefer, M. H. (2017) ‘HIPPIE v2.0: enhancing meaningfulness and reliability of protein–protein interaction networks’, Nucleic Acids Research, 45(Database issue), pp. D408–D414. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw985.

Blohm, P. et al. (2014) ‘Negatome 2.0: a database of non-interacting proteins derived by literature mining, manual annotation and protein structure analysis’, Nucleic Acids Research, 42(Database issue), pp. D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1079.

Chen, M. et al. (2019) ‘Multifaceted protein–protein interaction prediction based on Siamese residual RCNN’, Bioinformatics. Oxford Academic, 35(14), pp. i305–i314. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz328.

Engin, H. B., Kreisberg, J. F. and Carter, H. (2016) ‘Structure-Based Analysis Reveals Cancer Missense Mutations Target Protein Interaction Interfaces’, PLOS ONE. Public Library of Science, 11(4), p. e0152929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152929.

Fragoza, R. et al. (2019) ‘Extensive disruption of protein interactions by genetic variants across the allele frequency spectrum in human populations’, Nature Communications. Nature Publishing Group, 10(1), p. 4141. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11959-3.

Gainza, P. et al. (2020) ‘Deciphering interaction fingerprints from protein molecular surfaces using geometric deep learning’, Nature Methods. Nature Publishing Group, 17(2), pp. 184–192. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0666-6.

Geng, C. et al. (2019) ‘iSEE: Interface structure, evolution, and energy-based machine learning predictor of binding affinity changes upon mutations’, Proteins, 87(2), pp. 110–119. doi: 10.1002/prot.25630.

Nambiar, A. et al. (2020) ‘Transforming the Language of Life: Transformer Neural Networks for Protein Prediction Tasks’, bioRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, p. 2020.06.15.153643. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1818. 10.1101/2020.06.15.153643.

Rao, R. et al. (2019) 'Evaluating Protein Transfer Learning with TAPE', bioarxiv, doi.org/10.1101/676825

Zhou, G. et al. (2020) ‘Mutation effect estimation on protein–protein interactions using deep contextualize d representation learning’, NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics. Oxford Academic, 2(2). doi: 10.1093/nargab/lqaa015.

DB: To replicated the PPIDB, HuRI psi files for H-I-05, H-II-14, and HuRI must be downloaded and placed in the HuRI folder in ppiDB. Similarly, the HIPPIE dataset must be downloaded and placed in the HIPPIE folder. These files were not uploaded due to size restraints.

CD-HIT: Install CD-HIT from cdhit and use the default settings with `-c 0.7'when running the clustering program using a fasta file containing all sequences between 50 adn 2000 AA long.