#es6 #assembler-school #master-in-software-engineering

In this workshop you will learn the main features of ES6 and beyond.

- Getting Started

- Workshop Material

- var vs let vs const

- Block Scopes

- Default Function Parameters

- Arrow Functions

- Destructuring

- New Array Methods

- ES Modules

- Promises

- fetch

async/await- Template Literals

- Classes

First, you will need to clone the repo:

$ git clone https://github.com/assembler-school/es6-workshop.gitThen, you will have to install all the dependencies with npm:

$ npm installFirst, let's start with the differences between var, let and const.

One of the major changes introduced in ES6 is how we can declare variables.

In ES5 and before, we could only declare variables with the var keyword.

In ES6 we have two new ways to declare variables using let and const which were introduced to solve some of the issues we had when working with variables declared with the var keyword.

In JavaScript, variables declared with the var keyword hoist. This means that we can use them before we declared them without the runtime throwing an exception.

If we access the variable before it is initialized, we can read its value, which will be undefined even if we have assigned a value to it.

// => "Alex"

console.log(myName);

var myName = "Alex";In JavaScript, if we don’t explicitly declare a variable we use in the program, the variable will be automatically created as a global variable

This can be solved by turning on the strict mode of executing JavaScript or by simply declaring all the variable we use ✅.

// This automatically creates a global variable

// with the name `myAge` and the value of 30

//

// This is considered to be a very bad practice

// You should avoid writing this type of code

myAge = 30;

console.log(myAge); // 30By turning on strict mode we can run catch these kind of issues because the language will throw an error.

"use strict";

// ReferenceError: myAge is not defined

myAge = 30;

console.log(myAge); // 30Variables that are declared using the let or const keywords do not hoist, which means that we cannot use them before we define them.

// console.log(jobTitle);

// ^

// ReferenceError: Cannot access 'jobTitle' before initialization

console.log(jobTitle);

let jobTitle = "Developer";Variables that are declared using the let or const keywords cannot be accessed before the line of code where we initialize them.

Before this line, let and const variables are in a TDZ (Temporal Dead Zone) in which we cannot read or change the contents of the variables.

// Start of our program

//

// Start of the TDZ

// console.log(jobTitle);

// ^

// ReferenceError: Cannot access 'jobTitle' before initialization

console.log(jobTitle);

let jobTitle = "Developer"; // End of the TDZVariables that are declared using the var keyword are initialized with a default value of undefined if we access them before the variable is initialized.

On the other hand, variables declared with let or const are not initialized with any value and trying to read or change their values will cause an error.

console.log(myName); // undefined

var myName = "Alex";

// Start of the TDZ

// Uncaught ReferenceError:

// Cannot access 'jobTitle' before initialization

console.log(jobTitle); // uninitialized

let jobTitle = "Developer"; // End of the TDZVariables declared with let are not initialized with a value because the language also introduced the const keyword.

If a variable declared with const were initialized with a value of undefined, it would have two different values which would go against the theoretical meaning of a constant variable. It would first have a value of undefined and then it would have the value we assigned to it.

Since both let and const were introduced at the same time, the creators of the JavaScript language specified that both let and const should be in a TDZ until the variables are initialized. Therefore, let and const variables are not initialized.

Variables that are declared using the var keyword can be redeclared as many times as we want and still be the same variable. On the other hand, variables created with let cannot be redeclared.

var myName = "Ana";

console.log(myName); // Ana

// `myName` is a label to the same variable

var myName = "Hello I am Ana";

console.log(myName); // => Hello I am Ana

let myAge = 30;

console.log(myAge); // => 30

let myAge = 40;

// Output:

// let myAge = 40;

// ^

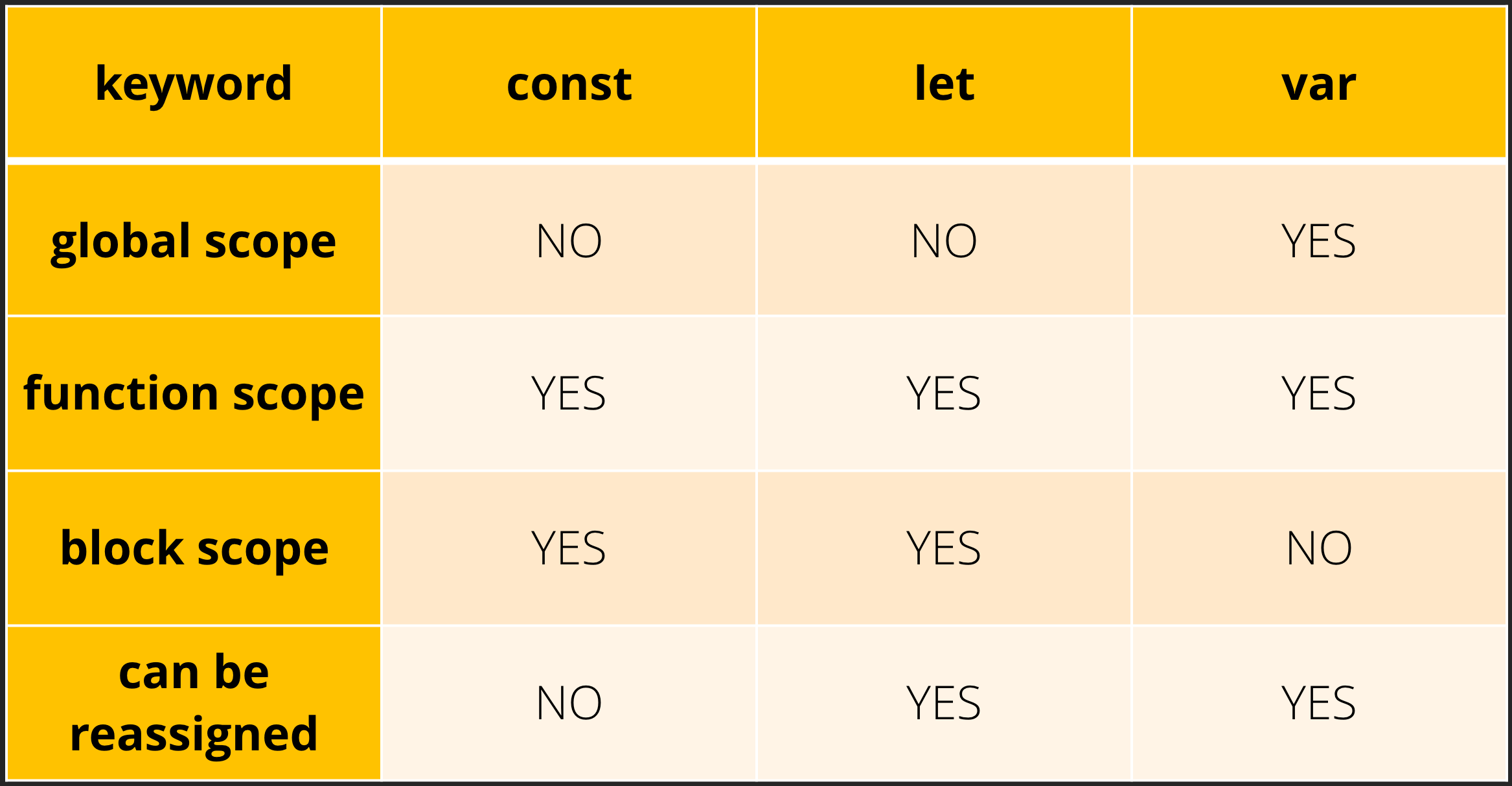

// SyntaxError: Identifier 'myAge' has already been declaredVariables that are declared using the var keyword have a global or a function scope. Variables declared with let or const create a block scope besides the function scope that var also create.

function sayVarName() {

if (true) {

// var is only function scoped

var myName = "Alex";

}

// The name variable is available in the entire scope of the function

console.log(myName); // Alex

}

function sayLetName() {

if (true) {

// let is block scoped

let myName = "Alex";

}

// ReferenceError: myName is not defined

console.log(myName);

}A block scope is created when we use a let or const variable inside a function, a if/else, if/else if/else statement, a switch statement, try/catch, etc.

// global scope and block

let count = 1;

console.log(count); // => 1

// declares a block inside the function

function myName() {

let count = 2;

console.log(count); // => 2

// declares a block inside the if statement

if (true) {

let count = 3;

console.log(count); // => 3

}

}Other ways of creating a block scope:

{

let firstName = "Dani";

console.log(`My name is: ${firstName}`); // => My name is: Dani

}

console.log(`I am: ${firstName}`); // => ReferenceError: firstName is not definedPre ES6, setting a default value to one of the parameters of a function was pretty verbose and long to write.

function compute(num, times) {

if (num === undefined) {

num = 1;

}

if (times === undefined) {

times = 1;

}

return num * times;

}

let num1 = compute();

console.log(num1); // => 1

let num2 = compute(2);

console.log(num2); // => 2

let num3 = compute(2, 2);

console.log(num3); // => 4In ES6, now it is much easier to set a default value to the parameters of a function if we don’t provide an argument for each parameter.

// Now it is much easier to set a default value

function compute(num = 1, times = 1) {

return num * times;

}

let num1 = compute();

console.log(num1); // => 1

let num2 = compute(2);

console.log(num2); // => 2

let num3 = compute(2, 2);

console.log(num3); // => 4Passing undefined as an argument will trigger the parameter to take the default value.

function compute(num = 1, times = 1) {

return num * times;

}

let num1 = compute(undefined, 20);

console.log(num1); // => 20

let num2 = compute(undefined, undefined);

console.log(num2); // => 1Pre ES6, we could define functions using the function keyword.

Functions could be named or anonymous and they could be stored as the value of a variable.

// function declaration

function sum(a, b, c) {

return a + b + c;

}

// named function expression

var sum = function sum(a, b, c) {

return a + b + c;

};

// anonymous function expression

var sum = function (a, b, c) {

return a + b + c;

};In ES6, we can use a new syntax of creating function with arrow functions.

// ES5

var sum = function sum(a, b, c) {

return a + b + c;

};

// ES6

// Can be written with an anonymous function as:

// Explicit function body and return statement

const sum = (a, b, c) => {

return a + b + c;

};

// ES5

var sum = function (a, b, c) {

return a + b + c;

};

// ES6

// Can be written with an anonymous function as:

// Implicit return statement

const sum = (a, b, c) => a + b + c;Arrow functions are always anonymous

const arr = ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday"];

// The callback function is anonymous, if an error occurs inside it,

// it will be more difficult to debug because it will not have

// a name in the stack trace of the error

arr.map((day) => {

console.log(day);

if (day === "Wednesday") {

throw new Error("BAD DAY");

// Error: BAD DAY

// at /es6-workshop/src/main.js:10:11

}

});If we assign a name to the callback function we will be able to see the function name that caused the error:

const arr = ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday"];

arr.map(function logName(day) {

console.log(day);

if (day === "Wednesday") {

throw new Error("BAD DAY");

// Error: BAD DAY

// at logName (/es6-workshop/src/main.js:10:11)

}

});Anonymous functions can be written in different ways depending on the number of parameters of the function.

const fn1 = () => {}; // no parameter

const fn2 = (x) => {}; // one parameter, an identifier

const fn3 = (x, y) => {}; // several parametersAnonymous functions can have an implicit return statement if the function body is a single line of code. If not, we need to specify the function body in {} and include an explicit return statement if we want to return a value from the function.

// block

const fn1 = (x) => {

return x * x;

};

// expression, equivalent to previous line

const fn2 = (x) => x * x;Destructuring is a convenient way of extracting multiple values from data stored in (possibly nested) objects and arrays.

It can be used in locations that receive data and the way to extract the values is specified via destructuring patterns.

Before ES6 we had to capture the values individually using dot notation and store them in variables.

With ES6 we can capture the values in an easier way using a destructuring pattern to save the values in variables.

const person = {

firstName: "Jane",

lastName: "Doe",

};

// ES5 Way

const firstName = person.firstName;

const lastName = person.lastName;

console.log(firstName); // Jane

console.log(lastName); // Doe

// ES6 Way

const { firstName, lastName } = person;

console.log(firstName); // Jane

console.log(lastName); // DoeIf the property don’t exist on the object we can provide a default value which will be used when the property is undefined.

const person = { firstName: "Jane" };

// ES5 Way

const lastName = person.lastName || "Doe";

console.log(lastName); // Doe

// ES6 Way

const { firstName, lastName = "Doe" } = person;

console.log(lastName); // DoeWe can also destructure nested objects and their properties, but we need to provide a fallback default object for when the nested object doesn’t exist.

const person = { firstName: "Jane" };

const {

// We can also destructure both the object and its properties.

// Destructure the entire nested object:

address = {},

// Or the properties it has:

address: {

street,

// We need provide a fallback `{}`

// if the object doesn’t exist in the source:

} = {},

} = person;

console.log(address); // => {}

console.log(street); // => undefinedOtherwise we get a TypeError for trying to access a property on the undefined value.

const person = { firstName: "Jane" };

const {

// If we don’t provide a fallback {} we will get an error.

address: { street },

} = person;

console.log(street); // => TypeError: Cannot read property 'street' of undefinedDestructuring can also be used to capture data from arrays and, in the same way as with objects, we can provide default values.

// we can skip elements with an empty comma

// the `last` item has a default value

let [zero, , , third, , , last = "Empty"] = [

"Monday",

"Tuesday",

"Wednesday",

"Thursday",

"Friday",

];

console.log(zero); // Monday

console.log(third); // Thursday

console.log(last); // EmptyWe can use the ...rest operator to capture individual values in variables and all the other variables in an array.

It can also be used in functions to capture the parameters.

const [x, ...y] = ["a", "b", "c"];

console.log(x); // x = 'a';

console.log(y); // y = ['b', 'c']

// also works with function parameters

function args(a, b, ...rest) {

console.log(a); // 1

console.log(b); // 2

console.log(rest); // [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

}

args(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7);// Destructure function parameters

function removeBreakpoint({ url, line, column }) {

console.log(url); // => "the-url"

console.log(line); // => 33

console.log(column); // => 60

}

let options = {

url: "the-url",

line: 33,

column: 60,

};

removeBreakpoint(options);

function returnMultipleValues() {

return {

foo: 1,

bar: 2,

};

}

// Destructure the returned value of a function

const { foo, bar } = returnMultipleValues();

console.log(foo); // => 1

console.log(bar); // => 2function weekDays() {

return ["Monday", "Tuesday", "Wednesday"];

}

// Destructure the returned value of a function

const [monday, ...otherDays] = weekDays();

console.log(monday); // => Monday

console.log(otherDays); // => ["Tuesday", "Wednesday"]The Array.from() static method creates a new, shallow-copied Array instance from an array-like or iterable object.

// Array from a String

const arr = Array.from("foo"); // => [ "f", "o", "o" ]

// Array from a Set

const set = new Set(["foo", "bar", "baz", "foo"]);

Array.from(set); // => [ "foo", "bar", "baz" ]

// Array from an Array-like object (arguments)

function createArray() {

return Array.from(arguments);

}

createArray(1, 2, 3); // => [ 1, 2, 3 ]The Array.flat() method creates a new array with all sub-array elements concatenated into it recursively up to the specified depth.

const arr1 = [1, 2, [3, 4]];

arr1.flat(); // => [1, 2, 3, 4]

const arr2 = [1, 2, [3, 4, [5, 6]]];

arr2.flat(); // => [1, 2, 3, 4, [5, 6]]

const arr3 = [1, 2, [3, 4, [5, 6]]];

// Use a flattening depth of 2 for nested arrays

arr3.flat(2); // => [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

const arr4 = [1, 2, [3, 4, [5, 6, [7, 8, [9, 10]]]]];

// Use a flattening depth of Infinity for nested arrays

arr4.flat(Infinity); // => [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]The Array.includes() method determines whether an array includes a certain value among its entries, returning true or false as appropriate.

const array1 = [1, 2, 3];

console.log(array1.includes(2)); // => true

const pets = ["cat", "dog", "bat"];

console.log(pets.includes("cat")); // => trueThe Array.find() method returns the value of the first element in the provided array that satisfies the provided testing function.

Otherwise, it returns undefined, indicating that no element passed the test.

const array1 = [5, 12, 8, 130, 44];

// const found = arrar1.find(elem => eleme > 10);

const found = array1.find(function (element) {

return element > 10;

});

console.log(found); // => 12The Array.findIndex() method returns the index of the first element in the array that satisfies the provided testing function.

Otherwise, it returns -1, indicating that no element passed the test.

const array1 = [5, 12, 8, 130, 44];

const found = array1.findIndex(function (element) {

return element > 10;

});

console.log(found); // => 1Modules allow us to split our code in different files so that we can better reuse, organize, modularize, and maintain our code.

We can either declare several functions or variables that we export as named exports, or we can declare a default export that will be the default exported function or variable exported from the entire module.

// Open the utils.js file to practice

// src/es-modules/utils.js

// Named exports

export function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

export function minus(a, b) {

return a - b;

}

const BASE_VALUE = 20;

// Default export

export default BASE_VALUE;Once we have declared a set of modules, we can import both the named exports as the default exports.

// Open the imports.js file to practice

// es-modules/imports.js

// import a named export

import { add } from "./utils";

// import a default export

import BASE_VALUE from "./utils";

const result1 = add(1, BASE_VALUE);

// Result is: 21

console.log(`Result is: ${result1}`);There are multiple ways that we can use to default export a module.

// es-modules/default-exports.js

// method 1

const names = ["Ana", "Alex", "Mark", "John"];

export default names;

// or with the second method

export default ["Ana", "Alex", "Mark", "John"];

// modules-main.js

// They would all be imported this way:

// We can specify any name that we would like to use for the module

import names from "./default-exports";

console.log(names); // => ["Ana", "Alex", "Mark", "John"]We can also create a namespace for all the modules we have created so that we can import all of them under a base name that we can use to call them.

// es-modules/namespace.js

export function trimPassword(password) {

return password.trim();

}

export function encryptPassword(encrypt, password) {

return encrypt(password);

}

/**

* Run the `npm run start` script and open in the browser

* the following url: http://localhost:1234/

*

* Then, you should open the ES Modules link and the

* browser console to you should see the output

*/

// modules-main.js

import * as utils from "./es-modules/namespace.js";

function encrypt(string = "") {

return string.toUpperCase();

}

const encryptedPassword = utils.encryptPassword(encrypt, "my-password-1234");

console.log(encryptedPassword); // => MY-PASSWORD-1234We can also create a namespace for all the modules we have created so that we can import all of them under a base name that we can use to call them.

// namespace.js

export function trimPassword(password) {

return password.trim();

}

// modules-main.js

import { trimPassword as shortenPassword } from "./es-modules/namespace";

const password = shortenPassword(" 12345 ");

console.log(password); // 12345Due to the nature of modern JavaScript applications that mostly rely on building their interfaces dynamically, we need a way to communicate with remote servers asynchronously without blocking the rendering of the browser so that the user can still use the application or browser while the information is returned from the server.

Before we had promises in JavaScript the only way that we could execute asynchronous code was by using callbacks, setTimeout or setInterval. However, error handling and control flow of the execution of the code wasn’t very easy to handle and understand.

setTimeout(function performLongOperation() {

// performing a long operation

// that would block the UI...

}, 3000);

setInterval(function executeEverySecond() {

// a function that runs every second

// that shouldn’t block the UI...

}, 1000);Another problem of traditional JavaScript is that by using callbacks we could end up with what is commonly known as the callback hell…

This happens when we need to perform a network request that is based on the previous response.

// Each nested function depends on the result of the enclosing function.

// This creates a nested structure of function calls that depend on each other.

loginUser(function (user) {

getUserDetails(user, function (userDetails) {

getUserCart(userDetails, function (cart) {

getCartItems(cart, function (cartItems) {

getCartItemComments(cartItems[0], function (comments) {

console.log(comments);

});

});

});

});

});The previous code could be refactored to use promises which allows us to avoid having a callback hell, to have more readable code and to be able better handle errors.

loginUser()

.then((user) => {

return getUserDetails(user);

})

.then((userDetails) => {

return getUserCart(userDetails);

})

.then((cart) => {

return getCartItems(cart);

})

.then((cartItems) => {

return getCartItemComments(cartItems[0]);

})

.then((comments) => {

console.log(comments);

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error);

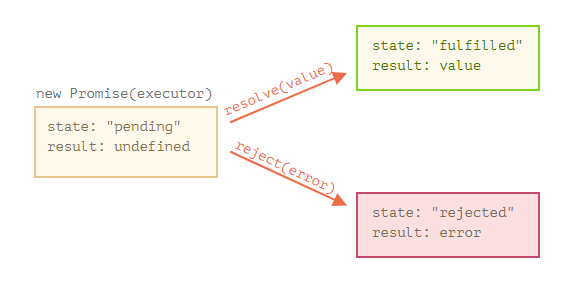

});To create a Promise, we simply call the Promise constructor and pass it two callback functions that we can execute to indicate that the Promise has been resolved or rejected with a value.

function task() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve("Hello world");

}, 500);

});

}

const myPromise = task();

console.log(myPromise); // => Promise {<pending>}

myPromise.then((result) => {

console.log(result); // => Hello world

console.log(myPromise); // => Promise {<fulfilled>: "Hello world"}

});To reject a Promise, we just need to execute the reject callback function with a value. It is recommended that you reject the promise with an Error object so that it contains useful information about the error like the error message and stack trace of where the error has happened.

function task() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

reject(new Error("Something went wrong"));

}, 500);

});

}

const myPromise = task();

console.log(myPromise); // => Promise {<pending>}

myPromise.catch((error) => {

// Something went wrong

console.log(error.message);

console.log(myPromise); // => Promise {<rejected>: Error: Something went wrong

});Promises can have 3 states.

pending: this is the base state of the promise before it is resolved or rejected.fulfilled: this is the state that the promise has after it has been resolved with a valuerejected: this is the state that the promise has after it has been rejected with an error

The fetch() method is a browser API that can be used in all the browsers that support ES6 to perform network requests using promises.

It was designed to achieve the same functionality as using XMLHttpRequest but in a more powerful way.

// Open the src/node-fetch.js file to test it with node or with the browser

fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users")

.then(function (response) {

return response.json();

})

.then(function (users) {

console.log(users);

});fetch() will only reject on network failure or if anything prevented the request from completing. These errors can be caught in the .catch() method.

fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users/")

.then(function (response) {

// fetch will only reject on network failure

// or if anything prevented the request from completing

// For any other error it will set the response.ok

// property to false

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error(`Request failed with: ${response.status}`);

}

return response.json();

})

.then(function (users) {

console.log(users);

})

.catch(function (error) {

// we can handle network errors in the .catch() method

console.log(error);

});We can also specify the different options we might use to define the request such as the request method, among others.

If you'd like to learn more about fetch, you can use this link: Fetch API

fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users/", {

// GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc.

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

},

// body data type must match "Content-Type" header

body: JSON.stringify({ firstName: "Dani" }),

}).then((response) => console.log(response.ok));async functions are a new feature of the language that allows us to work with promises in an easier way. The value returned by the async function will be wrapped in a resolved Promise.

// basic syntax of an `async` function

async function getUsers() {

return [];

}

// same as

function getUsers() {

return Promise.resolve([]);

}The await keyword can only be used inside async functions and it allows us to pause the execution of the function until the value we are awaiting is resolved or rejected.

async function getUsers() {

const response = await fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users/");

const users = await response.json();

console.log(users); // [{...}, {...}, {...}]

}The await keyword will wait until the promise is either rejected or resolved and it will either return the resolved value or it will throw the rejected error.

async function myFunction() {

let promise = new Promise((resolve, _reject) => {

setTimeout(() => resolve("done!"), 2000);

});

console.log("Before await"); // => Before await

// wait until the promise resolves (*)

let result = await promise;

console.log("After await"); // => After await

console.log(result); // => done!

}It is important to remember that we can only use the await keyword inside async functions, otherwise the language will throw an error.

// not an async function!!

function getUsers() {

// ERROR: Can not use keyword 'await' outside an async function

const response = await fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users/");

const users = await response.json();

console.log(users); // [{...}, {...}, {...}]

}The best way to handle errors with async/await functions is to wrap the code in a try/catch block.

function task() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

reject(new Error("Ups"));

}, 1000);

});

}

async function waitForTask() {

let result = "";

try {

result = await task();

} catch (error) {

result = error.message;

}

console.log(result); // Ups

}Template literals allow us to perform string concatenation in a much easier way than before.

const age = 20;

const name = "Ana";

// pre-ES6

var es5Ana = "My name is: " + name + " and I am " + age + " years old";

// ES6

const es6Ana = `My name is: ${name} and I am ${age} years old`;Template literals also make it easier to create multi-line string.

console.log("string text line 1\n" + "string text line 2");

// "string text line 1

// string text line 2"

console.log(`string text line 1

string text line 2`);

// "string text line 1

// string text line 2"Tagged template literals allow us to perform an operation on each of the strings and variables of the template literal received.

function tag(strings, expression1, expression2, expression3) {

console.log(strings); // => ["My name is ", ", I’m a "]

console.log(strings[0]); // => "My name is "

console.log(strings[1]); // => ", I’m a "

console.log(expression1); // => Ana

console.log(expression2); // => 30

console.log(expression3); // => developer

}

const name = "Ana";

const age = 30;

const profession = "developer";

tag`My name is ${name}, I’m a ${age} ${profession}`;In ES6 JavaScript gained support for the class keyword, making it easier to program in a Object Oriented way.

class Animal {

constructor(name, species, age) {

this.name = name;

this.species = species;

this.age = age;

}

}

const dog = new Animal("Spark", "dog", 5);

// Animal

// {

// name: "Spark",

// species: "dog",

// age: 5

// }

console.log(dog);As in all other languages, classes can also have methods that we can call.

class Animal {

constructor(name, species, age) {

this.name = name;

this.species = species;

this.age = age;

}

saySpecies() {

console.log(this.species);

}

sayName() {

console.log(this.name);

}

}

const dog = new Animal("Spark", "dog", 5);

dog.saySpecies(); // => dog

dog.sayName(); // => SparkThe static keyword defines a static method for a class. Static methods are called without instantiating their class and cannot be called through a class instance. Static methods are often used to create utility functions for an application.

class Point {

constructor(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

static distance(a, b) {

const dx = a.x - b.x;

const dy = a.y - b.y;

return Math.hypot(dx, dy);

}

}

const p1 = new Point({ x: 5, y: 5 }, { x: 10, y: 15 });

console.log(p1.distance); // => undefined

console.log(Point.distance({ x: 5, y: 5 }, { x: 10, y: 15 })); // => 11.180339887498949The extends keyword is used in class declarations or class expressions to create a class as a child of another class.

class Animal {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

speak() {

console.log(`${this.name} makes a noise.`);

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

constructor(name) {

// call the super class constructor and pass in the name parameter

super(name);

}

speak() {

console.log(`${this.name} barks.`);

}

}

let d = new Dog("Mitzie");

d.speak(); // => Mitzie barks.The super keyword is used to call corresponding methods of the super class. This is one advantage over prototype-based inheritance.

class Cat {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

speak() {

console.log(`${this.name} makes a noise.`);

}

}

class Lion extends Cat {

speak() {

super.speak();

console.log(`${this.name} roars.`);

}

}

let l = new Lion("Fuzzy");

l.speak();

// Fuzzy makes a noise.

// Fuzzy roars.