This repository contains code written for global irrigation map project. This README documents key elements of the software architecture.

- See research paper for additional details

- If paywalled, see final preprint

- Results dataset available on Zenodo

- Concepts and how we built it: this blog post

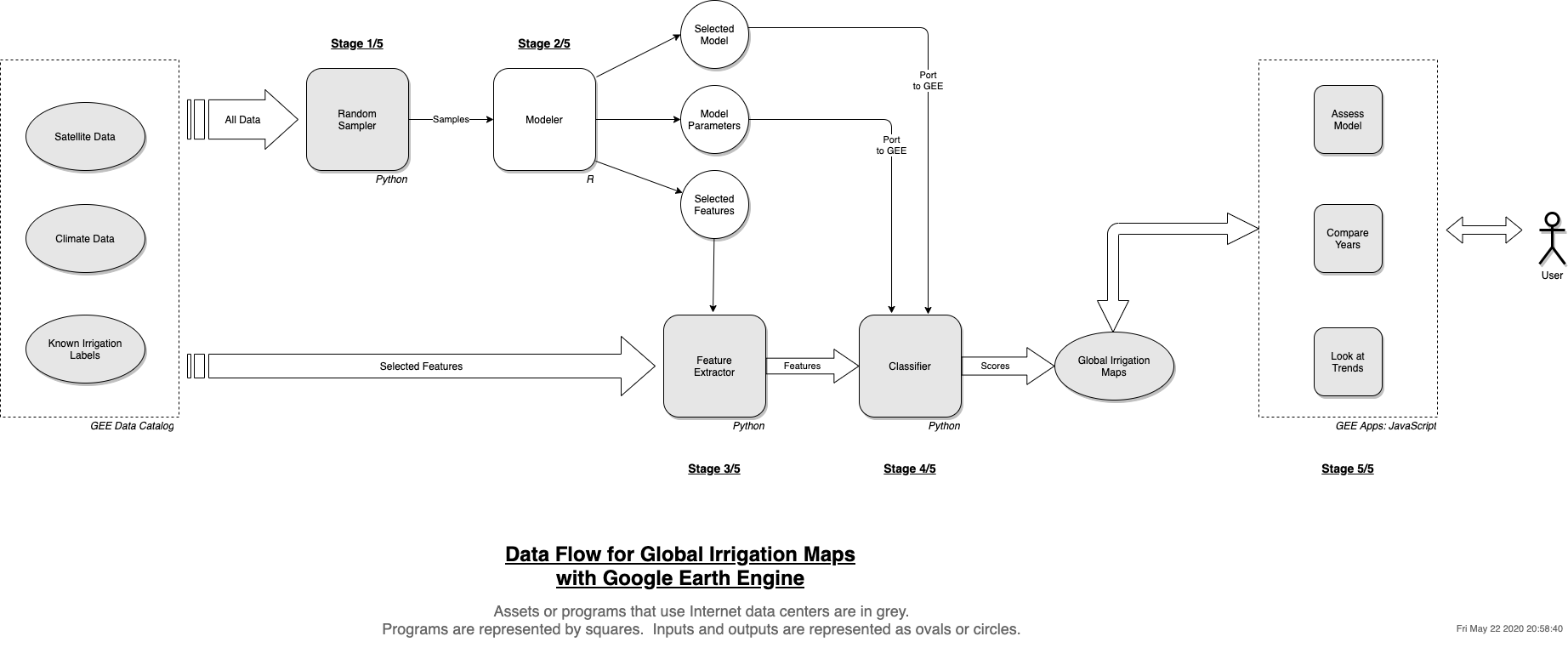

The following diagram captures the big picture of the software for the project. It uses Google Earth Engine in all but one of the stages.

Data flows from left to right. There are four stages in producing the maps, and a final stage of consuming the maps via interactive apps.

In the first stage, we take a random sample of the features we wish to explore and possibly use for our model. We took 10000 points for our model. The input is the features we want to use from within GEE; the output is a GeoJSON file that can be read as a spatial dataframe within R.

In the second stage, we analyze the sample to select features, select a classification algorithm, and also tune its hyper-parameters. We do this within R on our laptop.

In the third stage, we create features for our model. These are the features we selected in the previous stage. They will be stored as multi-band raster images within GEE, one per year of prediction, to be used directly as inputs in the next stage.

It might seem that this step is unnecessary. But doing feature processing as well as running the model becomes very expensive and leads to errors on GEE. It is better to have the features ready before running the model.

In the fourth stage, we run our ported model on the features we produced. We store the results within GEE as raster images.

Finally, we provide user access to the maps by developing interactive apps within GEE. These apps, written in JavaScript, allow us to compare irrigation across years, zoom into a region, or overlay satellite imagery to check if the map makes sense.

For the complete development workflow, we will need 2 environments. The first is in Python and is needed to run our programs that invoke Google Earth Engine APIs. The second is in R in order to do our data analysis and model development.

For Python, follow the official GEE documentation to set up a local conda environment. This repository uses Python 3 and will not work on Python 2.x. Be sure to run earthengine authenticate so that your credentials are saved on the computer.

For R, the two key packages you need are: sf, caret. Install them and their dependencies.

For GEE apps, it is best to develop within GEE code editor. You can clone the repository locally, but GEE code environment is richer: it allows you to see the maps and also inspect individual points.

After setting up all this, you can then fork and/or clone this repository. Be sure to work on a branch rather than master.

When you first clone this repository, set the base asset directory to your GEE directory path. In my case, I had "users/deepakna/w210_irrigated_croplands".

For this example, we will not do any model development. We will simply try to use what is already there. We will do a run for only one year.

Before you start a run, bump up the version in common.py. This is a best practice to ensure immutability. Commit after each version bump.

By default, it creates 10000 points. If you want, you can change it in sampler.py.

python3 training_sample_exporter.pyThis step takes about 20-30 minutes.

Keep only 2000 in the years list within features_exporter.py, then run it:

python3 features_exporter.pyThis step takes about 3 to 4 hours with the default set of features.

Again, be sure to keep only 2000 in the years list within classifier.py, then run it:

python3 classifier.pyThis step takes about 2 hours with the default model parameters.

There is a utility run.py that will run both steps 2 and 3 for you, if you prefer.

2000 is the year with training labels, so predicting on that year will allow you to assess model performance. Predicting on any other year will only give you the map for that year.

If you think you made a mistake, press Ctrl-c to stop the script. However, the job may be running on GEE servers. To stop it, go to the GEE code environment and use the "Tasks" pane.

More often, you will want to add or change features to your model and see how it performs. For example, you might want to try features from a new soil dataset within GEE. Here are the steps:

- Bump up the version

- If you want to try an additional feature in a known dataset, add your feature to the

dataset_listwithin common.py, underallBands. If it is a new dataset, copy an example dataset entry and update it to point to your new dataset location and features. Again, any features initially go toallBands. - Re-run training_sample_exporter.py to get a training sample.

- Copy the R notebook, point it to your new training sample, and run it. It takes about 15 minutes to run. Be sure to look at its final features, assessment results and tuned model parameters.

- If your feature was not significant, stop here.

- If your new feature was found to be significant, add it to

selectedBandsin the feature configuration. - Re-run features_exporter.py to create the new feature store.

- Update model parameters, if required, in classifier.py. Re-run classifier.py.

The model is currently at 8km spatial resolution. This is the same as the one for the labels that come from MIRCA2000 dataset.

If you want to improve the resolution to say 4km or 1km, there are two challenges.

First, there is the "data science" challenge of how to apply the 8km labels to a smaller parcel of land. You have to apply intelligence, such as use the label on a part of the original square that looks like cropland, based on some of its features, say the vegetation index.

Second, there is the engineering challenge, because data grows on a quadratic scale - i.e., you have an O(N2) problem at hand. You will likely run into GEE errors. When that happens, you should start by reduce the regions processed in parallel by feature extractor component in get_selected_features_image() function. For 8km scale, it splits the world into 2 collections of smaller regions. The same function is also used by the classifier, so your changes will automatically carry over to that component.

This component is set up to take a random sample worldwide. The code is careful enough to calculate areas for global land regions and assign the number of points to each region based on that. Oceania causes an explosion of geometries, therefore it limits that region to only New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. It uses the LSIB dataset on GEE to get the boundary polygons for each geographical region.

A key question here is how many samples to take. The answer is: "as many samples to capture all the data variability". In other words, if you have a high degree of class imbalance, you will need a larger sample to account for minority class variability. In practice, I looked at the map to see if there were enough points within the "irrigated" class, and 10000 seemed to be enough. There might be more statistical ways to do this too.

The sampler captures all the features in allBands key. This is to allow the next component to select features that are significant. It automatically includes latitude, longitude, and irrigation labels from MIRCA2000 dataset.

Code: sampler.py, training_sample_exporter.py

This component is in R, and uses the caret package to quickly and efficiently try out different models and tune them. The input is the sample taken earlier, read into an R dataframe. The choice of models to try is limited to what is available within GEE for us to run our final model: naive Bayes, SVM, random forest; random forest practically was the most effective. For speed of execution, the current code does not try any other models, but it is easy to try them within the caret framework.

The code uses 5-way cross validation to assess the model, and kappa as its assessment metric. It sets a tuning length of 10 in the final model, and uses the model itself to assess feature importance and select the most important features. A rough guide is to take the best tuned model, and keep adding features until you see the assessment metric to be within one standard error of the best model. Practically, a normalized feature importance score of 0.30 or above was enough in our case.

It is worth noting that the irrigation labels are highly skewed: the number of data points fall off exponentially as we look for higher extent of irrigation. We therefore do a log transformation (log1p) on the labels. Even so, our threshold is 1 log1p-Hectare, because the samples decrease drastically as we increase our threshold.

This is the only component that runs on the developer's machine. All others run on GEE infrastructure, although the scripts are invoked on the developer's machine. We went with this approach because we found GEE to be lacking in this area.

Code: gim_v2a.Rmd

After selecting features, we run a script to create them for the whole world, for a given year. If the dataset has multiple samples on a given year, we take a summary metric, such as the mean or maximum. This step is very resource intensive, because it touches all the data for all the samples in a given year. Processing is higher for data with finer spatial resolution (e.g., 500m as against 5km) and temporal resolution (e.g. once a month as against once a day). The component automatically includes latitude, longitude, and irrigation labels from MIRCA2000 dataset.

The result of this step is a multi-band image, where each band represents the summarized value for that feature for that year, for each land pixel. In our model, the resolution is 8km, and this means each pixel represents a square of 8km by 8km.

Code: features_exporter.py

We are finally ready to run our model. We now code the model that we have selected earlier with GEE API. We set its hyper-parameters based on our analysis, and set its input to the features we have selected as well. We then let it run.

The classifier produces a single band output image, where each pixel represents the probability that the model assigned for irrigation.

Code: classifier.py

The maps are now ready to be consumed. We write a few simple JavaScript applications and make them available on GEE as "apps".

These apps are available in a separate repository so that we can commit them directly to GEE. To reduce extra complexity, we don't use the git "submodule" feature.

These apps allow interaction, zooming, and overlay with satellite imagery for validation. GEE also allows us to customize the map style, introduce UI elements such as buttons and menus, and generally makes for a rich user experience.

If you wonder why we did not use JavaScript for the earlier stages, it is because there is no way to invoke JavaScript API from the developer's computer. You can have a copy of the code itself, but running anything requires pressing a button on the GEE code editor. Python API allow us to invoke GEE from the script directly.

It is also worth mentioning that any JavaScript code you write for GEE needs to be fast: it has a 5-minute timeout, but practically it has to run within milliseconds or the user will notice a lag. This timeout does not apply to code running under Python API.

We use irrigation labels from the MIRCA2000 dataset. The labels represent maximum area equipped for irrigation, on a global 8km by 8km grid. We created a GeoTIFF file from it. In addition to the original data, we also created a band that represents low, medium or high irrigation. We do not use this band, opting for the original data instead.

Our labels GeoTIFF image is available in this repository.

We now list down all those little things that may come useful to the developer.

- GEE evaluates lazily: that is, it does not start a job until you try to output it somewhere. At that point, it works backwards to see what needs to be done. As long as you specify your scale and projection at output, you do not have to worry about it anywhere else, because GEE will propage this backward.

- A second ramification of the way GEE executes your code is that you should not do

forloops. Instead, you should use functional equivalents such asmap(), so that GEE can continue to build its execution graph. - Be careful with changing the model resolution. This is an area, i.e. O(N2), problem, so it is best to change a little and adjust based on how GEE responds. The simplest strategy would be to reduce the processing geographical region, because we are now dealing with a larger volume of data.

- When taking the sample, GEE removes data that is masked (i.e., missing). Visualize your features within GEE code environment to get a sense before you add it to the model feature soup. For example, a dataset might be available only for the US or Europe. Add an appropriate

missingValuesparameter in the feature configuration to deal with such instances. - Similarly, visualize your results within GEE environment immediately and look for weirdness. Use the satellite layer to make some quick sanity passes over the results. In case of irrigation, it should not be showing large swathes of the Sahara as irrigated.

- Make good use of immutability and versioning. Bump up the version every time you do a new run, and archive or delete results that were meaningless. Use good commit logs so that you know what changed in each version. Use a code branch each time, instead of always working on the master. Each run takes many hours, so it is best not to let that go to waste.

- Do some software housekeeping periodically. It is easy to get carried away in model development, but badly written software will accrue "tech debt" that will come back to bite you. A rule of thumb is to see what parts you're changing, and somehow split it into mutable and immutable parts. For example, the current code base has a feature configuration dictionary that changes frequently, but its associated code does not change much.

Following are some ideas for further development on this project:

- Make a Docker image with both Python and R environments set up and ready to use.

- Add some code and plots for EDA of individual features.

- Feature engineering: there is ample scope to add more features, such as monthly values instead of an annual mean, or also adding variance in addition to mean.

- Create a time series movie of irrigation changing over time from 2000 to 2018.

- Improve the resolution for the maps from the current 8km.