The tool is deployed here: nikkelm.github.io/RepositoryGuide-Python, along with its documentation.

The aim of this proof-of-concept is to showcase how

software development teams can be enabled to

analyze their own development data using

interactive browser-based notebooks without any additional software.

The Enterprise System and Integration Concepts (EPIC) chair at the Hasso-Plattner-Institute (HPI) owns and develops the RepositoryGuide tool, which "aims at helping development teams gain insights into their teamwork based on the produced GitHub project data." The tool accesses data that is publicly available through the Github API to provide a variety of data analytics and visualizations to inform development teams about their work processes. Users can customize the tool by providing "Sprints" (time intervals) and "Teams" (Github users) which are used during the analysis.

The major downside of the current implementation of the tool (written in Javascript) is its static nature. Aside from the input provided through the configuration files, users cannot quickly make changes to the way the data is analyzed or visualized. However, given that the way in which teams work differs greatly not only between organizations and teams, but even between projects, it is important to enable users to customize the tool to fit their needs.

Such customization should not stop at the ability to change color schemes or time intervals that are analyzed, but should also allow users to add or remove visualizations, change input parameters, or even add completely new types of data analytics. Such major changes are not possible from within the tool with the current implementation, but would require users to download the tool's source code and host it on their own server. All the same, it is not feasible to try and add such functionality to the current implementation, as its tech stack does not work well with the required level of interactivity and creative freedom.

Instead, it was decided to try and prototype a new approach to the RepositoryGuide using Jupyter notebooks, which are known for their interactive nature. Moving from Javascript to Python would also relax the barrier to entry for non-technical users, as Python and Jupyter notebooks in particular are already widely used in the data science community, which is certainly a group of users that would benefit from the RepositoryGuide.

In this initial prototype, we wanted to test the feasibility of using Jupyter notebooks as a replacement for the current implementation of the RepositoryGuide. To do so, we wanted to meet the following requirements:

- The tool must be implemented using Jupyter notebooks, to test their feasability as a more interactive replacement for the current implementation.

- The tool must not require users to install or download any software. Most notably, users must not be required to have a Python installation on their machine. This is due to the fact that the tool is intended to be used by non-technical users, who are not to be expected to have any programming experience.

- The tool must be able to run in a browser.

- The tool must offer functionality to allow users to change the tool's functionality through code from within the tool itself, without the need to download any files.

- The tool must be able to access data required for the analysis using the Github API, and not require users to provide more than the name of the repository in question to get started. As a minimum requirement, the commit history for a given repository should be accessed.

- The tool must provide at least one data visualization. (Note: This was chosen to be a heatmap of weekly commit activity)

- The tool must offer at least one interactive feature to influence the way the data is visualized using the previously mentioned visualization. (Note: Among others, this was chosen to be the ability to switch between an hourly and time-of-day based visualization).

- The abovementioned interactive feature should not require the user to refresh the page or re-run a code cell, but instead update the visualization in real-time.

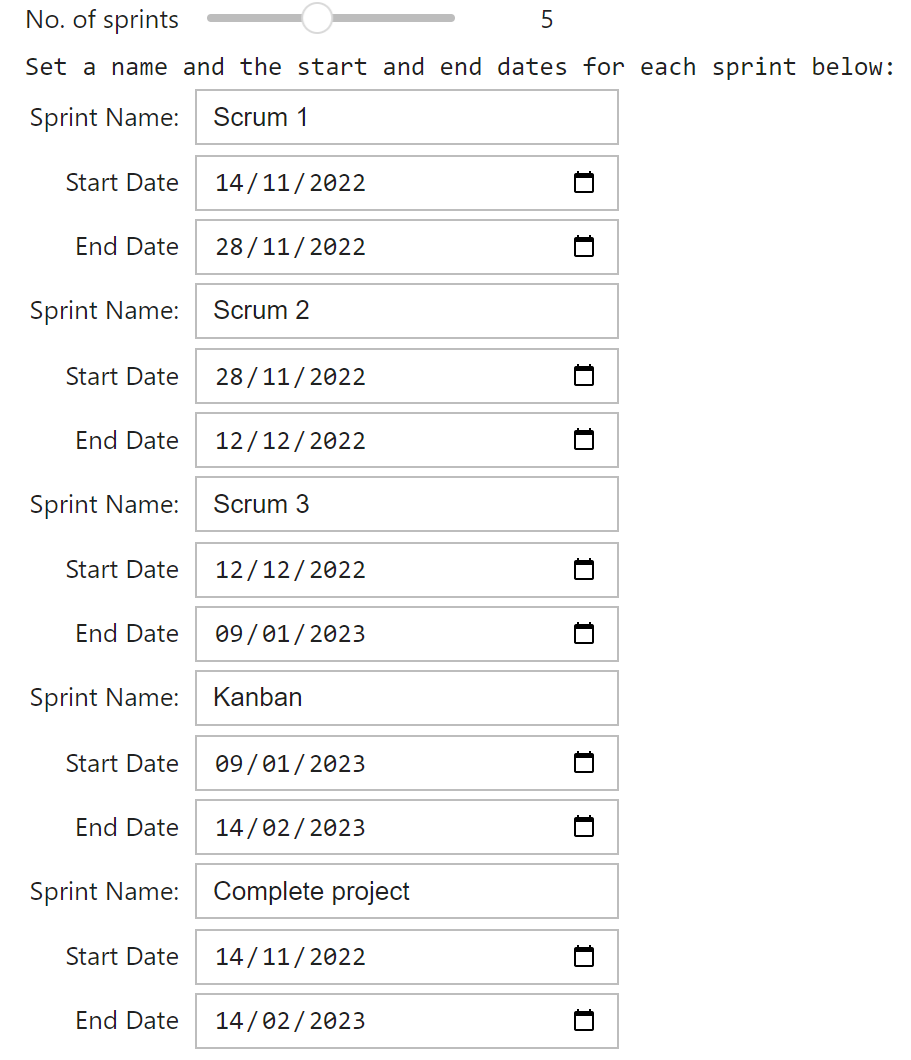

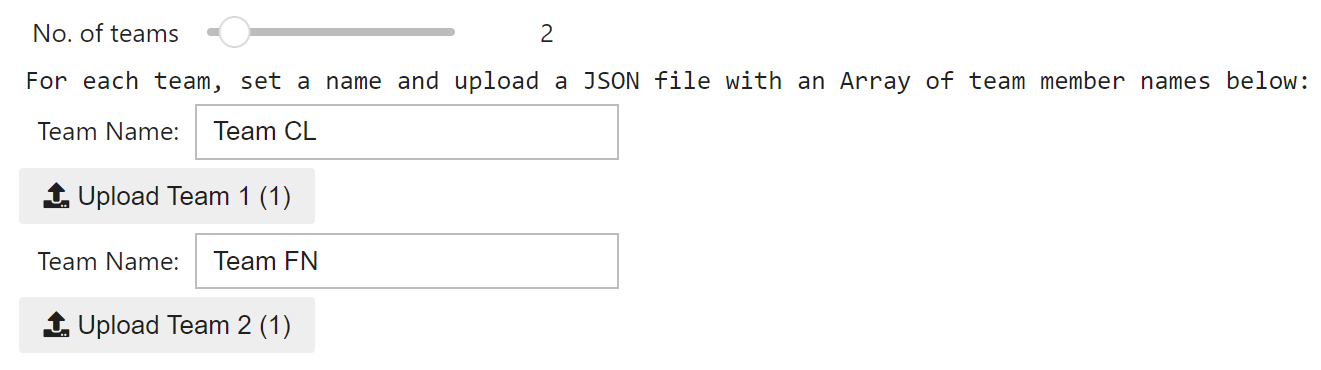

- The tool should offer the possibility to set a number of sprints and teams to be used to subdivide data during the analysis.

- These sprints and teams should be configurable interactively, without the need to provide extensive configuration files.

- The tool should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and use for non-technical users. Most importantly, the tool should only expose code cells when actively requested by the user, and otherwise only expose the interactive elements and visualizations.

Two external tools prompted the idea for this prototype, and their combination alone would allow us to meet a majority of the requirements:

JupyterLite is a JupyterLab distribution that runs entirely in the browser, using a Pyodide backed Python kernel running in a Web Worker. Through the use of JupyterLite, we would be able to meet the requirements 1 through 4, as we can host the tool's Jupyter notebooks using JupyterLite, which allows users to access, run and modify them from within their browser, without the need to install any software.

Mercury is a tool that enables users to turn Jupyter notebooks into interactive web applications. Using Mercury, we would be able to take the notebooks created or modified in JupyterLite, and turn them into an interactive app that would hide all code cells, and only expose the interactive elements and visualizations, as required by requirement 11. You can think of Mercury as a way to "compile" Jupyter notebooks into a static web app, as JupyterLite is in itself still more of an IDE than a frontend which would be used by an end user.

The ideal workflow would be to first create the initial notebooks with the tool's basic functionality locally on a developer's machine, which would then be hosted on a server using Mercury. This would be the frontend the user initially sees, and would allow them to use all of the tool's functionalities. If needed or desired, the user would then be able to access and edit the underlying notebooks and thereby add, change or remove functionality using JupyterLite, which would allow them to modify the tool's code to their liking without the need to download any files or external tools, before again converting it to an interactive app using Mercury.

So, we went ahead and set out to deploy a JupyterLite instance (to Github pages), which, thanks to a great template repository was no problem at all. The basic JupyterLite deployment already offers a great host of features. However, in order to be able to display interactive widgets (for which we would be using ipywidgets) or create visualizations (using plotly), we would need to install additional packages.

As we are working with Python, we can easily do so using a requirements.txt file. Such a file is already included in the template repository and initially contains packages that are required to run the JupyterLite instance itself.

The deployment workflow for JupyterLite installs all of those packages to the backend of the JupyterLite instance, which is the Python kernel running in the Web Worker.

However, in order to enable users to use those packages in their notebooks, they need to also be installed in the frontend of the JupyterLite instance, which is the user's local browser, as this is separated from the backend.

Luckily for us, it is quite easy to install additional pip packages form within a notebook using some pip magic:

%pip install ipywidgets plotly pandasRunning this command in the first code cell of the notebook installs the required packages to the frontend of the JupyterLite instance, and allows us to use them in the notebook.

Now, as you may remember we had planned on using Mercury to turn the notebooks we create in JupyterLite into an interactive web app. To do so, we would need to install the Mercury package and build our widgets and visualizations using it. As we know by know, we can easily do so using pip magic:

%pip install mercuryThis is however where we run into the first limitations of JupyterLite (and Pyodide), which is after all still in the early stages of development and still unofficial, even though it is being developed by core Jupyter developers:

As Pyodide runs completely in the browser, there are a number of limitations to what kind of packages can be installed to the frontend (meaning, which kind of packages can be run in the browser-based notebooks), most prominently, only packages that provide a pure Python wheel (.whl) on PyPI can be installed.

Unfortunately, Mercury does not provide a pure Python wheel, which means that we would need to package and host the wheel ourselves, which would create a lot of overhead, especially as we would need to do so for every new version of Mercury.

For the moment however, as we saw Mercury at the core of our tool, we decided to go for it, and package and host the wheel ourselves.

After a number of hacks and workarounds (including hosting our own fork of Mercury on PyPi), Pyodide was finally willing to install Mercury in our JupyterLite instance. However, this was not the end of our troubles, as we soon ran into another issues: Mercury, as complex as it is, of course has a number of dependencies. As you may have guessed, not all of those dependencies provide a pure Python wheel, which would mean that we would need to package and host those as well. Rather fortunately for us, we were able to find the final nail in the coffin of our hopes to use Mercury before we could even think about doing so: Some of Mercury's dependencies not only do not provide a pure Python wheel, but are not pure Python packages at all, containing a number of C extensions, which are unsupported by Pyodide.

Actually, this is not entirely true, as you are able to create a Pyodide package for such packages. But by doing so - to stay true to our coffin analogy - we would only dig ourselves a deeper grave, as we would then need to package and host not only Mercury, but also a number of its dependencies (which, to be honest, will probably also have some dependencies that are incompatible with Pyodide), for some of which we would also need to create Pyodide packages, and so on and so forth. All of this was simply not feasible for us as the prototype was supposed to be up and running in only a few weeks and juggling this amount of a dependency mess would certainly not be maintainable in the long run.

So we decided to put Mercury aside for the moment, and instead focus our attention on getting the prototype up and running using only JupyterLite (fortunately, this was not a major setback in the project, as Mercury was meant to be the nice "frontend" stuck on top of the JupyterLite instance, and not the core of the tool).

The next step would now be to implement the functionality that would allow us to fetch data from the Github API, which would then be used to create the interactive visualizations. There are a number of Python implementations of the Github API, but we decided to go with PyGithub, as it is the most popular one, and also the one that is most actively maintained. Again, we tried to install the PyGithub package using pip magic, and again, we ran into the problem that the package requires C extensions, in this case regarding cryptography and networking, which PyGithub uses for API requests such as signing commits among others.

However, as mentioned above, there are a lot if Python implementations of the Github API, and so we tried our luck with the next of the bunch, ghapi. This did not work out as well, as ghapi makes use of the _multiprocessing module, which is not supported by Pyodide on grounds of browser limitations.

As all good things come in threes, we tried a third implementation, github3.py (no, choosing the implementation with a three in its name third was not intentional). This may all sound very time consuming, but remember that all we had to do to find out whether or not a package would work was to try and install it to our JupyterLite frontend. At first we thought that this package would be "the one", as it was the only one so far that was able to be installed at all, but unfortunately, our hopes were once again crushed, as we ran into a shiny new error to add to our collection; this time, while trying to make a request to the Github API.

Obviously, any self-respecting implementation of the Github API will make its requests using HTTPS, and so does github3.py. Unfortunately, and for reasons I will not go into deeper here (though it once again has to do with C extensions and, obviously, networking), Pyodide does not support HTTPS requests. With this in mind, we had to abandon the idea of using any of the implementations of the Github API available to us within JupyterLite, as we would either not be able to even install many of them, or at the very least, we would not be able to use their functionality from within the browser.

However, not all hope was lost as it was with Mercury, as the interaction with the Github API is not something that must be done in the browser to prove the feasibility of our tool. At first, the idea was to simply fetch the data using PyGithub in a local environment, pickle it, and then load it again in the JupyterLite instance. This idea was quickly put to rest however, as we realized that in order to unpickle the data, we would need to still have PyGithub installed in our JupyterLite frontend, which as we know is not possible due to its C extensions.

Instead, we initially decided to go the simplest route possible, and simply dump the data retrieved using PyGithub to a JSON file, which we would then load in the JupyterLite instance.

This was not too far-fetched, as the Github API natively returns the data in JSON format.

PyGithub then parses this data to Python objects, but still keeps the original JSON data, which we can access using the raw_data attribute of the respective objects.

Unfortunately, even with this workaround, this would leave us with two of our requirements unfulfilled:

- 5: Accessing the Github API from within the JupyterLite instance - instead, the data must be pre-fetched and provided using a JSON file, which is then loaded in the notebook we are running in the JupyterLite instance.

- 11: Even though one might argue that Jupyter notebooks in general are easy to use even for non-technical users, it is clear that without Mercury, the tool is not as easy to use or visually appealing as it could have been. And with JupyterLite being aimed at developers, its interface may be conceived as confusing or cluttered by non-technical users. Even though hiding code cells is possible, this is not the default.

The work described in this section was done shortly before project end, and after writing the rest of the documentation. Therefore, knowledge and progress described here are not considered in later sections.

Once the bulk of the rest of the project was done (see below), we took another look at how we might be able to use the Github API from within the JupyterLite instance.

We found that it is possible to use Javascripts fetch function from within Python using some of the functionality we get from using Pyodide (see here or here), which would allow us to send the required requests to the Github API.

This greatly simplifies matters, as we can simply circumvent all Python implementations of the API and just directly send HTTPS requests using the Javascript workaround.

The only problem we are now (at the end of the prototyping phase) still facing is the fact that it seems we are as of yet unable to add headers to our fetch requests, which we would need to do in order to authenticate ourselves against the Github API (For those interested, the error we get when uncommenting the relevant lines and running the cell is the very uninformative JsException: TypeError: Failed to fetch, for which there do not seem to be any solutions online).

We can still make the necessary requests, but without authentication the amount of requests we can make is limited, meaning that users will need to make sure they do not run the cell too often.

So, what did we manage to achieve by now, and where do we go from here? Whilst we had to drop both the usage of Mercury to "beautify" the JupyterLite instance as well as using the Github API to fetch the required data, we did manage to get a running instance of JupyterLite, together with (most importantly) all of the packages we would henceforth be using to build our prototype:

ipywidgets- as the name suggests, we will be using this package to create interactive widgets that give the user control over the visualizations.plotly- this package will be used to create the visualizations themselves; in the case of our prototype, we opted for a heatmap of commit activity for each day of the week plotted against either the hour or time of day.pandas- in order to make use of theplotly.expressmodule (used to create the heatmap),pandasneeds to be installed as well, even though we will not be using it directly.

From here on out everything was pretty straightforward: We created a notebook that loads the data we previously provided in a JSON file, displays some widgets that allow for setting sprints and teams, and then creates the heatmap using plotly.express.

We encountered no more major roadblocks, but only smaller annoyances, such as the fact that ipywidgets's file upload widget is not yet supported in VSCode, which made testing some things very tedious, as we had to mock the data we would have uploaded.

Another thing that we had to work out how best to work with was how to handle widgets that not only set a variable in the notebook, but also trigger a change in the cell's output. This can get problematic as we would need to have a way to dynamically update certain parts of a cell's output, without touching other outputs (such as other widgets).

The most prominent example of this in the prototype is the final cell of the notebook, where the user is presented with three dropdown widgets to select for which sprint, team, and "time mode" the heatmap should be computed, which is then displayed below, within the same cell's output. If the user changes any of the values in the dropdowns, the heatmap must be updated, but the dropdown widgets themselves must not necessarily be touched. Unfortunately, it is not enough to update the heatmap figure, as the output will not get updated that way (if you will, the output is not "passed by reference" but rather "passed by value").

The most idiomatic way to solve this would be to use IPython's clear_output function (from the IPython.display module), which is supposed to clear all output of a given cell and replace it with newly provided output.

However, as we have already established, we would like to only update certain parts of our output, and not the entire cell.

Additionally, we have found that the method, especially when using the optional wait parameter, does not correctly clear a cell's output in JupyterLite, instead doing nothing at all, which makes it useless to us.

THe solution we came up with instead was to use (and abuse?) the ipywidgets.Output() widget, which is a widget that acts as a container for other outputs.

You are able to add different outputs to the output widget using the append_display_data method, and then display all output at once by simply displaying the output widget itself.

Internally, the output widget uses a list to keep track of its children, so whenever we want to change one output without affecting the others, we simply replace the output (such as the heatmap) at the appropriate index in the list.

Opposite to how updating the figure itself would not update the displayed output, replacing an output within the output widget's "output" list will update the output, in a way that does not affect other outputs.

With the completed prototype, we are now able to visualize commit activity for a given repository. By providing sprint timings and lists of teams, we add additional ways to filter the data that is being used to generate the heatmap. This allows us to compare productivity between sprints and teams (as far as the number of commits can be taken as a measure of productivity), as well as to see how commit activity may change between different days.

For our example, we are running the tool on the commit data of the Bookkeeper Portal Red repository, which is a project that was created by students of the HPI in the context of the "Scalable Software Engineering" course. Work on the project was started in November 2022 and concluded in early February 2023. The teams worked in a total of four sprints, the first three of which were worked on using the Scrum framework, while the last one was dedicated to Kanban.

For our use case, all four sprints and their corresponding date ranges were provided, alongside two exemplary student teams that worked on the project:

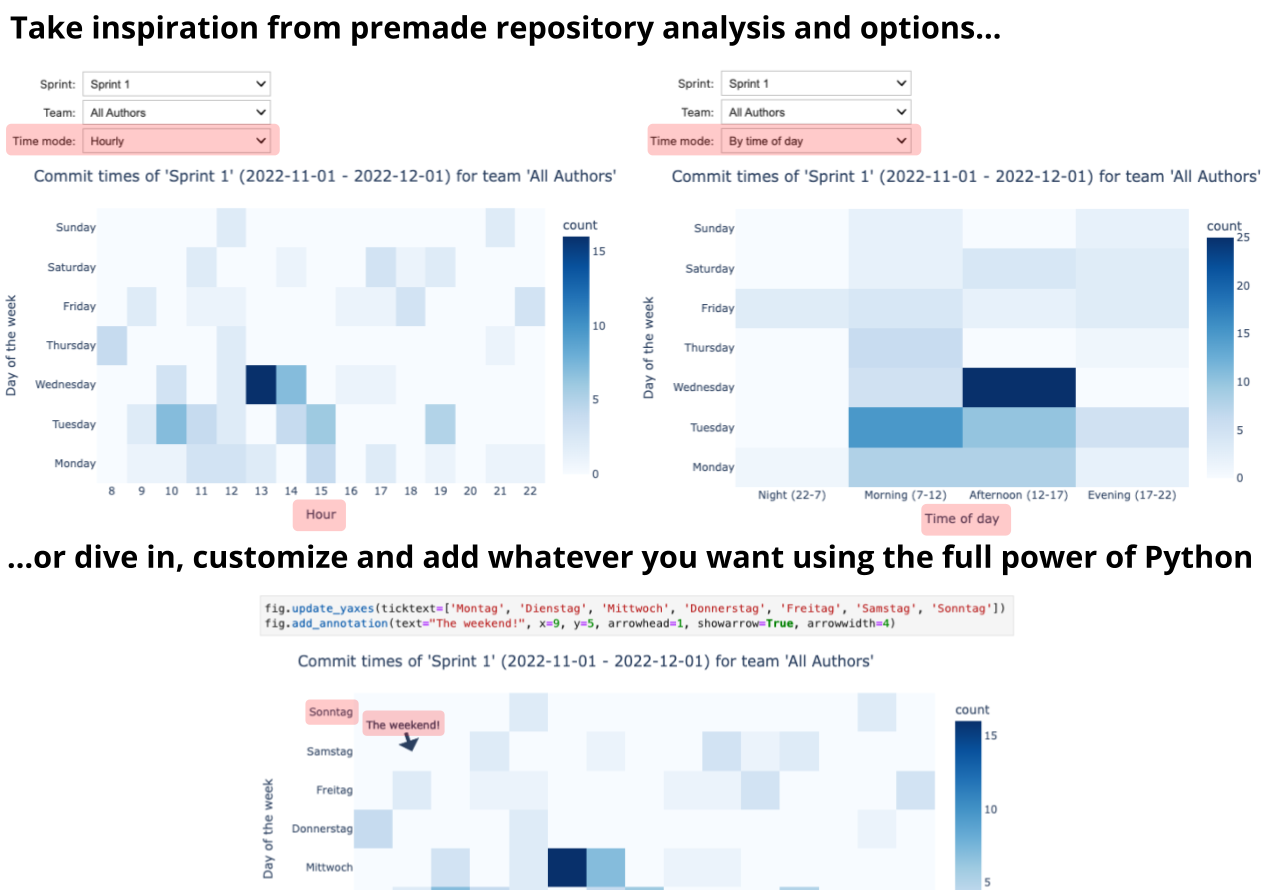

This results in the following interactive heatmap, generated by running the final cell of the notebook. Using the three dropdown menus at the top of the output, users can change between sprints, teams, and the "time mode" (either hourly or time of day) at will, which will automatically update the displayed heatmap with the new data, without the need to re-run the cell.

So, what can we take away from this?

First of all, it is very noticeable that a disproportionally high number of commits were made between 3 and 5 PM on Wednesdays when looking at all authors that worked on the project during its lifetime. This can be explained by the fact that students were encouraged to work on the project during those times, as the course had reserved those times in the student's schedules.

We can also see that teams tended to make more commits during the final Kanban phase of the project. This is likely due to the fact that this final project phase was dedicated to smaller bugfixes, which should automatically result in more commits made than during a feature-heavy sprint. So, with only a few data points, we can already see some interesting patterns emerging in the data that we can use to draw conclusions about the project's development process.

Users can use the tool to interactively explore all kinds of data, find patterns and improve the productivity of their teams. With the project being based on Jupyter notebooks, it is also very easy for any user to fit the tool to their organization's individual needs, without the need to wait for lengthy deployments or to install any additional software. As the tool is completely browser-based, any user can quickly and easily access it from anywhere, without having to have a technical background.

Overall, I am very happy with what I was able to achieve with this prototype. Especially in comparison with the current, static version of the tool, the interactivity this prototype provides is a huge improvement, even though this comes at a cost:

As was mentioned before, JupyterLite is a very powerful tool, but it also restricts us in the kind of packages we can use. Early on, I noticed this when I was unable to integrate Mercury, which would have allowed me to improve the user experience of the prototype - now, users are presented with a raw Jupyter notebook, which may be intimidating to some. Later on, I was unable to directly integrate the Github API into the prototype, which directly impacts the usability of the tool, by requiring users to acquire the required repository data themselves through other means. Shipping this tool without a tool like Mercury to "beautify" the technical interface is not advisable, and shipping it without a built-in way to interface with the Github API is downright counterintuitive, as it is deeply intertwined with the tool's purpose.

Still, I would think that this prototype is a great proof of concept and hope that in the future, one way or another, it will be possible to overcome these obstacles.