Bounding Volume | partial | partial | accepts | seconds

| accepts | accepts | |

------------------------------------------------------------------

AABB MIN,MAX | 0 | 152349412 | 39229 | 4.8294

AABB X,Y,Z | 34310232 | 1154457 | 39229 | 4.1507

7-Sided AABB | 0 | 172382 | 39229 | 3.0046

AABO | 0 | 67752 | 33793 | 2.1660

Tetrahedron | 0 | 0 | 67752 | 0.3200

In computer graphics and computational geometry, a bounding volume for a set of objects is a closed volume that completely contains the union of the objects in the set. Bounding volumes are used to improve the efficiency of geometrical operations by using simple volumes to contain more complex objects. Normally, simpler volumes have simpler ways to test for overlap.

The axis-aligned bounding box and bounding sphere are considered to be the simplest bounding volumes, and therefore are ubiquitous in realtime and large-scale applications.

There is a simpler bounding volume unknown to industry and literature. By virtue of this simplicity it has nice properties, such as high performance in space and time. It is the Axis-Aligned Bounding Simplex.

In 3D, a closed half-space is a plane plus all of the space on one side of the plane. A bounding box is the intersection of six half-spaces, and a bounding tetrahedron is the intersection of four.

In two dimensions a simplex is a triangle, and in three it is a tetrahedron. Generally speaking, a simplex is the fewest half-spaces necessary to enclose space: one more than the number of dimensions, or N+1. By contrast, a bounding box is 2N half-spaces.

In three dimensions a simplex has four (3+1) half-spaces and a bounding box has six (3*2). That’s 50% more work in order to determine intersection.

We will work in two dimensions first, since it is simpler and extends trivially to three dimensions and beyond.

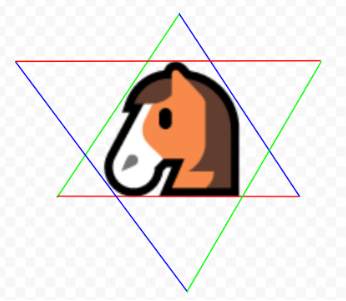

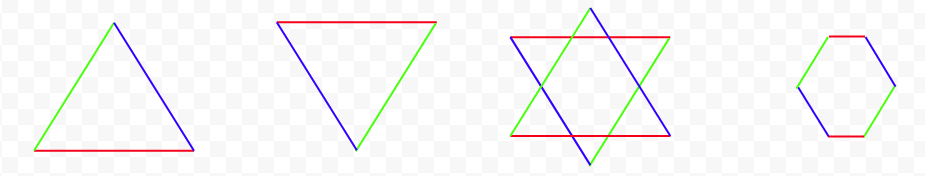

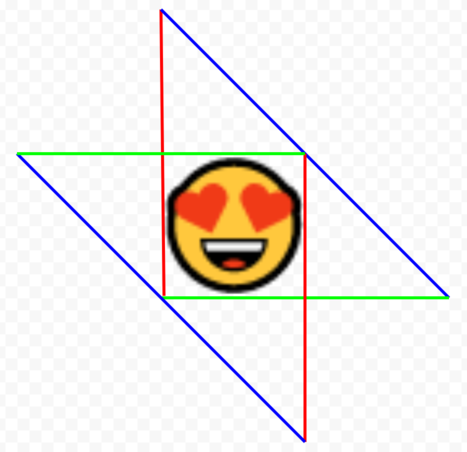

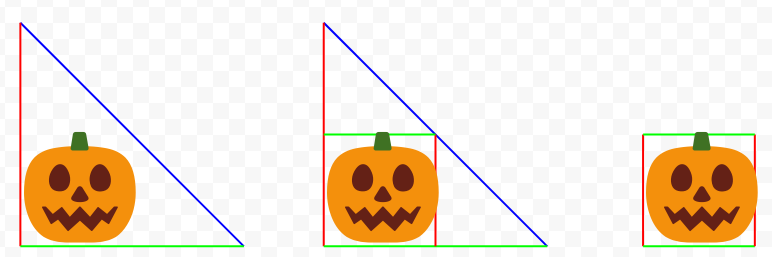

AABB is well-understood. Here is an example of an object and its 2D AABB, where X bounds are red and Y are green:

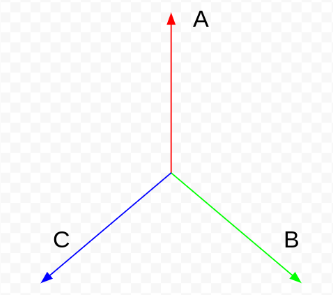

The axis-aligned bounding triangle is not as well known. It does not use the X and Y axes - it uses the three axes ABC, which could have the values {X, Y, -(X+Y)}, but for simplicity’s sake let’s say they are at 120 degree angles to each other:

The points from the horse image above can each be projected onto the ABC axes, and the minimum and maximum values for A, B, and C can be found, just as with AABB and X, Y:

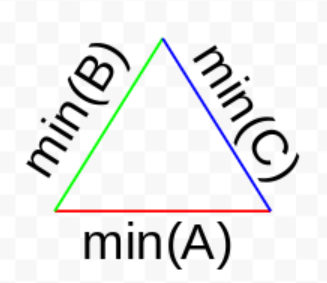

Interestingly, however, {maxA, maxB, maxC} are not required to do an intersection test. {minA, minB, minC} define an upward-pointing triangle, so we can use that in isolation as a bounding volume:

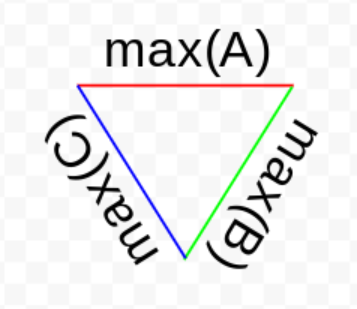

To perform efficient intersection tests against a group of objects bounded by {minA, minB, minC}, your query object would need to be in the form of {maxA, maxB, maxC}, which defines a downward-pointing triangle:

struct UpTriangle

{

float minA, minB, minC;

};

struct DownTriangle

{

float maxA, maxB, maxC;

};

When testing for intersection, if the down triangle's maxA < the up triangle's minA (or B or C), the triangles do not intersect. The above triangles don't intersect, because maxA < minA.

bool Intersects(UpTriangle u, DownTriangle d)

{

return (u.minA <= d.maxA)

&& (u.minB <= d.maxB)

&& (u.minC <= d.maxC);

}

If we stop here, we have a novel bounding volume with roughly the same characteristics as AABB, but needing 3 instead of 4 values in 2D, and 4 instead of 6 values in 3D, 5 instead of 8 in 4D, etc. If your only concern is determining proximity and you don't care if the bounding volume is tight, this is probably the best you can do.

struct Triangles

{

UpTriangle *up; // triangles that point up

};

bool Intersects(Triangles world, int index, DownTriangle query)

{

return Intersects(world.up[index], query);

}

If you don't have a DownTriangle handy, you can find the smallest DownTriangle that encloses an Uptriangle, like so:

DownTriangle UpTriangle::GetCircumscribed()

{

const float ABC = minA + minB + minC;

return DownTriangle{minA - ABC, minB - ABC, minC - ABC};

}

And should you need the largest DownTriangle enclosed by an UpTriangle...

DownTriangle UpTriangle::GetInscribed()

{

const float ABC = (minA + minB + minC) * 0.5;

return DownTriangle{minA - ABC, minB - ABC, minC - ABC};

}

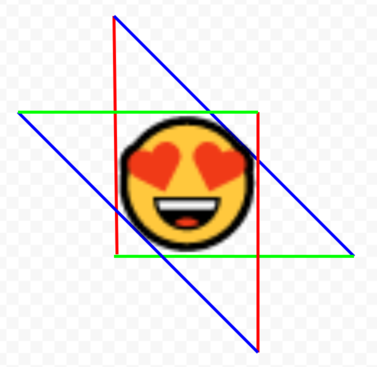

We can layer on another set of triangles to get even tighter bounds than AABB, while remaining faster than AABB. And, since the first layer remains, we can continue to do fast intersections with it alone when speed is most important. In addition to the up-pointing bounding triangle, we can have a down-pointing bounding triangle, and the intersection defines an axis-aligned bounding hexagon:

The axis-aligned bounding hexagon has six half-spaces, which makes it 50% bigger than a 2D AABB with four half-spaces:

struct Box

{

float minX, minY, maxX, maxY;

};

struct UpTriangle

{

float minA, minB, minC;

};

struct DownTriangle

{

float maxA, maxB, maxC;

};

struct Hexagons

{

UpTriangle *up; // triangles that point up, one per hexagon

DownTriangle *down; // triangles that point down, one per hexagon

};

However, the hexagon has the nice property that it is made of an up and down triangle, each of which can be used in isolation for a faster intersection check. And, when checking one hexagon against another for intersection, unless they are almost overlapping, one triangle test is sufficient to determine that the hexagons don't intersect.

Therefore, except in cases where hexagons almost overlap, a hexagon-hexagon check has the same cost as a triangle-triangle check.

bool Intersects(Hexagons world, int index, Hexagon query)

{

return Intersects(world.up[index], query.down)

&& Intersects(query.up, world.down[index]); // this rarely executes

}

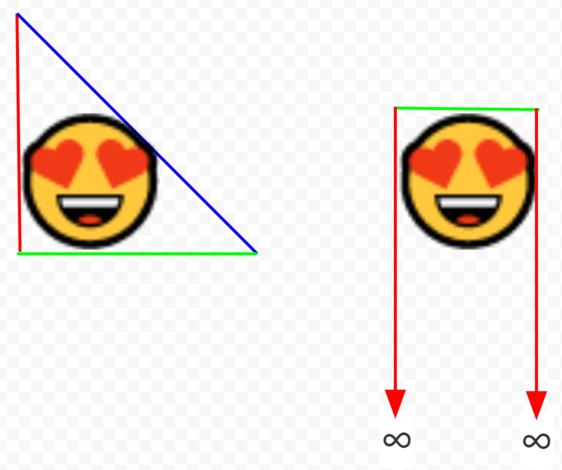

No three of a 2D AABB's four half-spaces define a closed shape. If you were to try to check for intersection with less than four of an AABB's half-spaces, the shape defined by the half-spaces would have infinite area. This is larger than the finite area of an hexagon's first triangle. That is the essential advantage of the hexagon.

For example, {minX, minY, maxX} is not a closed shape - it is unbounded in the direction of +Y. The same is true of any three of a 2D AABB's four half-spaces. The {minA, minB, minC} of a hexagon, however, is always an equilateral triangle, and so is {maxA, maxB, maxC}.

In 2D, a hexagon uses 6/4 the memory of AABB, but takes 3/4 as much energy to do an intersection check.

And... a hexagon can do two flavors of fast hexagon-triangle intersection check, in addition to hexagon-hexagon checks. None produce false negatives. An AABB offers nothing like that.

bool Intersects(Hexagons world, int index, UpTriangle query)

{

return Intersects(query, world.down[index]);

}

bool Intersects(Hexagons world, int index, DownTriangle query)

{

return Intersects(world.up[index], query);

}

Everything above extends trivially to three and higher dimensions. In three dimensions, an axis-aligned bounding box, axis-aligned bounding tetrahedron, and axis-aligned bounding octahedron have the following structure:

struct Box

{

float minX, minY, minZ, maxX, maxY, maxZ;

};

struct UpTetrahedron

{

float minA, minB, minC, minD;

};

struct DownTetrahedron

{

float maxA, maxB, maxC, maxD;

};

struct Octahedra

{

UpTetrahedron *up; // tetrahedra that point up, one per octahedron

DownTetrahedron *down; // tetrahedra that point down, one per octahedron

};

AABO uses 8/6 the memory of an AABB, but since only one of the two tetrahedra need be read usually, an AABO check uses 4/6 the energy of an AABB check. And an AABO has 8/6 the planes, for making a tighter bounding volume.

If your data is in an AoS (Array of Structures) (e.g. struct AABB{ vec3 min, max };) and your code is anywhere near data-bound, as it should be if performance is your concern, AABB will use 50% more energy to intersect than AABO, as explored above.

But what about the case of SoA (Structure of Arrays)? It's possible with AABB to organize data like so:

struct AABBs

{

vector *minX, *minY, *minZ;

vector *maxX, *maxY, *maxZ;

}:

int Intersects(AABBs world, int index, AABB query)

{

int mask = all_lessequal(world.minX[index], query.maxX)

& all_lessequal(query.minX, world.maxX[index])

if(mask == 0)

return 0; // can avoid reading all but first 2 data

mask &= all_lessequal(world.minY[index], query.maxY)

mask &= all_lessequal(query.minY, world.maxY[index])

if(mask == 0)

return 0; // can avoid reading all but first 4 data

mask &= all_lessequal(world.minZ[index], query.maxZ)

mask &= all_lessequal(query.minZ, world.maxZ[index]);

return mask;

}

The above code checks first if the object intersects the query in the interval {minX,maxX}, and only if an intersection is found, it proceeds to check Y and Z. This is often a pretty good idea, as most queries and objects are fairly small compared to the world they inhabit, so the probability of one intersecting the other in any one-dimensional interval is pretty small.

Whenever this initial interval check strategy is a good idea, we can do it with AABO as well:

struct Octahedra

{

vector *minA, *minB, *minC, *maxD;

vector *maxA, *maxB, *maxC, *maxD;

}:

int Intersects(Octahedra world, int index, Octahedron query)

{

int mask = all_lessequal(world.minA[index], query.maxA)

& all_lessequal(query.minA, world.maxA[index]);

if(mask == 0)

return 0; // can avoid reading all but first 2 data

mask &= all_lessequal(world.minB[index], query.maxB)

mask &= all_lessequal(query.minB, world.maxB[index])

if(mask == 0)

return 0; // can avoid reading all but first 4 data

mask &= all_lessequal(world.minC[index], query.maxC)

mask &= all_lessequal(query.minC, world.maxC[index]);

if(mask == 0)

return 0; // can avoid reading all but first 6 data

mask &= all_lessequal(world.minD[index], query.maxD)

mask &= all_lessequal(query.minD, world.maxD[index]);

return mask;

}

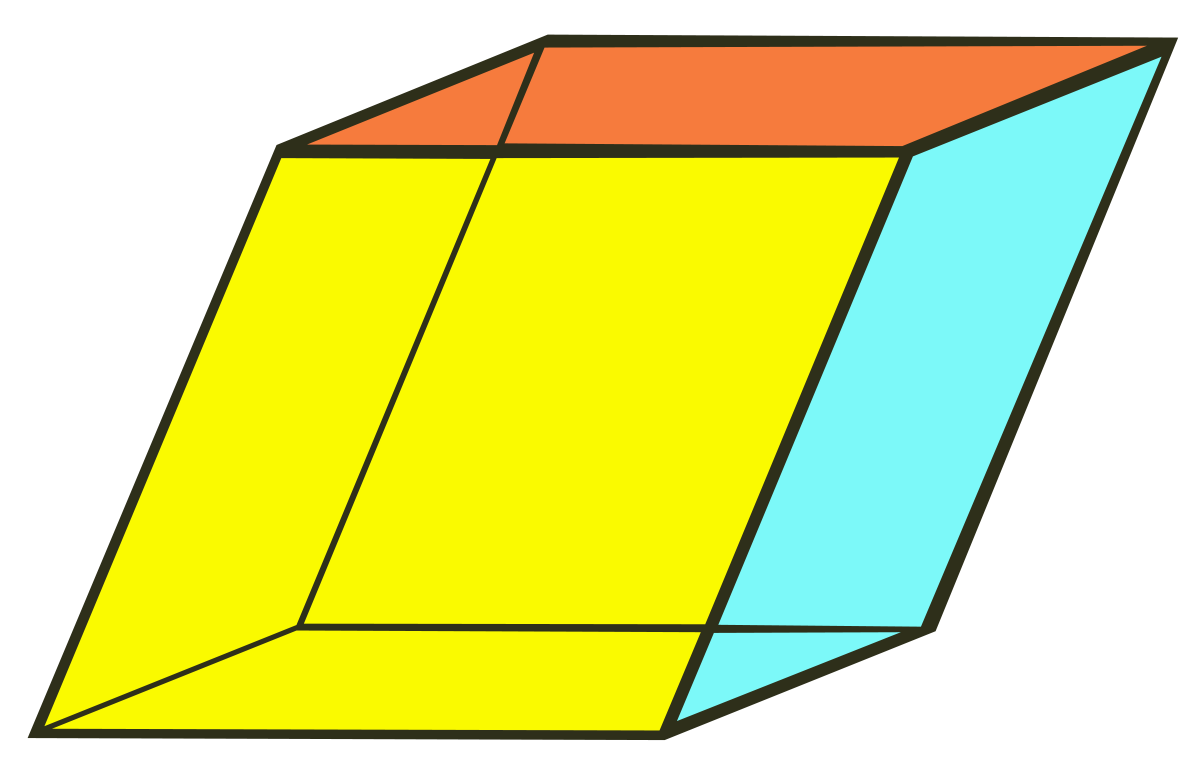

The first six planes generate identical code in AABB and AABO. In either case the shape enclosed by the six planes is a rhombohedron. It is quite unlikely that the AABO test will actually perform the D plane test.

Unfortunately for AABB, this initial interval check strategy is not always a good idea.

An initial interval check is not effective when the probability of an object intersecting the slab is high. When it is 80% likely for an object to intersect the slab, then the test has only a 20% chance of avoiding the next four plane tests, which means for AABB on average 0.8 tests are avoided, for an average of 5.2 plane tests per object. This is more expensive than an AABO's initial tetrahedron test with 4 planes total.

An initial interval check is not effective when the degree of SIMD in the target platform is high. This is because, if just one lane intersects the slab, we can't take the branch to avoid reading in more data.

On platforms such as GCN there are 64 SIMD lanes. For all of them to report no intersection with a slab 4% likely to intersect, the probability is 0.9664 or 0.073. That means for AABB an average of 5.7 plane tests, more than the AABO's initial tetrahedron test with 4 planes total.

In cases where probability of slab intersection is a few percent, and degree of SIMD is 8 or more, their effects combine to make the initial interval check ineffective. In these cases, AABO can fall back on its initial tetrahedron check:

bool Intersects(AABBs world, AABB query)

{

if(IntervalCheckIsSmart())

return IntervalIntersect(world, query);

else

return IntervalIntersect(world, query); // oh no

}

bool Intersects(Octahedra world, Octahedron query)

{

if(IntervalCheckIsSmart())

return IntervalIntersect(world, query);

else

return TetrahedronIntersect(world, query); // nice

}

AABB can not choose an alternate strategy for when the initial interval check isn't worth doing. And, AABO is never slower than AABB at doing an initial interval check. So, we can say that in SoA, AABO is never worse than AABB, and sometimes better.

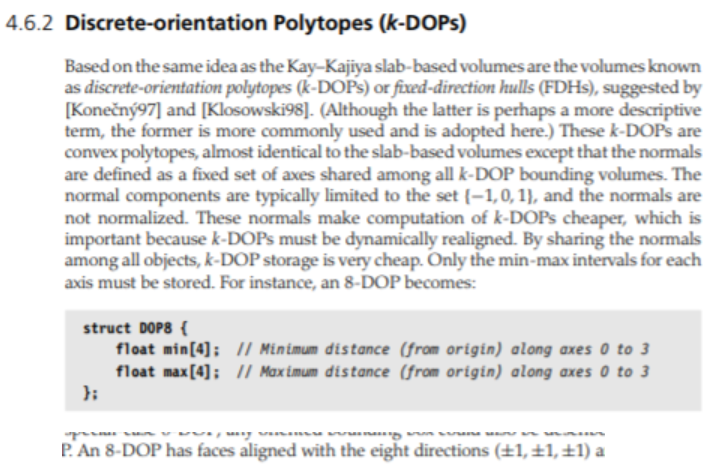

Christer Ericson’s book “Real-Time Collision Detection” has the following to say about k-DOP, whose 8-DOP is similar to Axis Aligned Bounding Octahedron:

k-DOP is similar to the ideas in this paper, in the following ways:

- Every AABO is also expressible as an 8-DOP, which has the same octahedral shape.

k-DOP is different from the ideas in this paper, in the following ways:

- A tetrahedron doesn't have opposing half-spaces, so it is not a k-DOP; there is no such thing as a 4-DOP in 3D.

- 8-DOP is four sets of opposing half-spaces, and AABO is two opposing tetrahedra. An 8-DOP can have opposing tetrahedra, but nowhere in literature can we find anyone mentioning this or making use of it, despite its large performance advantage.

- An 8-DOP can not have opposing tetrahedra if all of its axes point into the same hemisphere. Nowhere can we find discussion of how axis direction affects an 8-DOP’s ability to have opposing tetrahedra, which is required to avoid reading 50% of its data.

- A good example of this is the hexagonal prism, which is an 8-DOP but can not be an AABO.

- AABO is necessarily SOA (structure-of-arrays) to avoid reading 50% of data into memory unless it's needed, and 8-DOP is AOS (array-of-structures) in all known implementations.

struct Octahedra

{

UpTetrahedron *up; // in different cacheline than

DownTetrahedron *down; // this

};

struct DOP8

{

float min[4]; // maybe not a tetrahedron, in same cacheline as

float max[4]; // this, which maybe isn't a tetrahedron.

};

A bounding sphere has four scalar values - the same as a tetrahedron:

struct Tetrahedron

{

float A, B, C, D;

};

struct Sphere

{

float X, Y, Z, radius;

};

In terms of storage a sphere can be just as efficient as a tetrahedron, but a sphere-sphere check is inherently more expensive, as it requires multiplication and its expression has a deeper dependency graph than a convex polyhedron check.

If the data are stored in very low precision such as uint8_t, the sphere-sphere check will overflow the data precision while performing its calculation, which necessitates expansion to a wider precision before performing the check.

Convex polyhedra have no such problem. Their runtime check requires only comparisons, which can be performed by individual machine instructions in a variety of data precisions.

A bounding sphere can have exactly one shape, but each AABO can be wide and flat, or tall and skinny, or roughly spherical, etc. So, in comparison to an AABO, a bounding sphere may not have very tight bounds.

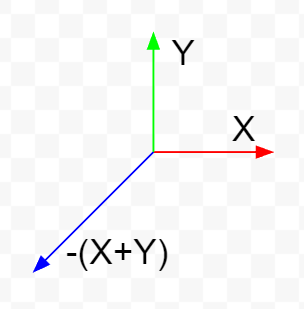

Though axes ABC that point at the vertices of an equilateral triangle are elegant and unbiased:

Transforming between ABC and XY coordinates is costly, and can be avoided by choosing these more pragmatic axes:

A=X

B=Y

C=-(X+Y)

The pragmatic axes look worse, and are worse, but still make triangles that enclose objects pretty well. With these axes, it is possible to construct a hexagon from a pre-existing AABB, that has exactly the same shape as the AABB, and where the final half-space check is unnecessary:

{minX, minY, -(maxX + maxY)}

{maxX, maxY, -(minX + minY)}

This hexagon won't trivially reject any more objects than the original AABB, but the hexagon will take less time to reject objects, because there are (usually) 3 checks instead of 4.

At first, the three half-spaces of a triangle are checked, and only if that check passes, two more half-spaces are checked. The intersection of the five half-spaces is identical to the four half-spaces of a bounding box, but in most cases, only the first three half-spaces will be checked.

In 3D the above needs 7 half-spaces, and is equivalent to a 3D AABB. In all tests I made, this 7-Sided AABB outperforms the 6-Sided AABB. The 7th half-space - the diagonal one - serves no purpose, other than to prevent maxX, maxY, and maxZ from being read into memory. Once they are read into memory, it becomes superfluous, as above.

If you construct the hexagon from the object's vertices instead, you can trivially reject more objects than an AABB can:

{minX, minY, -max(X+Y)}

{maxX, maxY, -min(X+Y)}

If it's unclear how a hexagon is superior to AABB when doing a 3 check initial trivial rejection test, the image below may help to explain. Even if you were to do 3 checks first with an AABB, no matter which 3 of the 4 checks you pick, the resulting shape is not closed. It fails to exclude an infinite area from the rejection test.

If you liked this paper, but suspect that a tetrahedron is a poor bounding volume for the skyscraper in your videogame, you are correct! For you, there is this paper, instead: Hexagonal Prism