If we want to look at SoundCheck with a relatively broad perspective what we can see is - It is software that samples sequences of symbols from a given Context Free Grammar (CFG). Now any CFG can be defined as a collection of terminals and non-terminal symbols. The sequences that are going to be sampled are going to be of these terminals which in our class of CFGs are going to be musical notes.

This project is an effort to sample Taan (sequence of musical notes distributed over a given beat-scheme) from a given Raag (a CFG). Now, the meanings of the words Taan and Raag in the context of this project are more nuanced that this and have been explained on. Here I will just try to describe the content and aim of this project in a nutshell. The content is two-folds.

- A scripting language is defined, using which the user can provide a Raag. I will talk about what this exactly means later on.

- Some algorithms have been decided upon to be used for generating Taan for this Raag. Though, these algorithms will have to be improved to improve the performance and basically has to move toward solving the problem, "What capacities enable human beings to generate Taan for a given Raag ?".

You will have to have java (jdk 1.8) installed in your machine. If you have this, download the release - SoundCheck.jar. Then go into the folder where you have saved the SoundCheck.jar file and open a .raag file, enter the raag (alternatively you can also copy from some of the examples you will find in the 'src/test/raag_files'), the go into the command prompt and run the following command.

java -jar SoundCheck.jar "<fileName>"

It is hard to explain what a raag is. Exponents of the Indian classical music tradition have been unanimously of this opinion. Now I here will try to define the subject as interpreted in this project. Here the Raag is interpreted as a recursive syntactic structure with musical notes as terminals. A Raag in my view is an infinite set of distinct sequences of notes. And the only way to capture and represent an infinite set of sequences is to have a generative structure. So a Raag here is essentially a generative structure.

A Taan is basically a sequence of notes sampled from a Raag and distributed over a given bit scheme or Taal.

Every Raag as an arohan and an avarohan. These are basically the subset of 12 notes that the Raag uses while ascending, Arohan or descending, Avarohan. These sometimes may also have patterns, which is beyond the current scope of this project.

Now, given the Arohan and Avarohan of a particular Raag, we can declare numerical patterns, Palta. Now depending on the Arohan and Avarohan these patterns can be applied to specific notes to get respective sequences of notes. We will see how exactly this works.

Now let's take a more intricate look into the first objective of the project. Now hierarchically speaking a .raag file should have three components. Declarations, An optional Scheme Block, a mandatory Rule Space.

The declarations are a set of parameters that are mentioned to describe some features associated with processing the Raag(syntax) and the subsequent operations related to generation of Taan(sequence or notes). This component constitute the header of a .raag file. Some declarations are obligatory and others are optional.

- beatsPerCycle (number): This parameter mentions the beat scheme or Taal, i.e., the number of beats in one cycle.

- numCycles (number): This parameter mentions the number of cycles the notes have to be played for.

- Range (string): This is the parameter used to mention the range for the scaling feature.

- outFile (string): This feature is for the name of the .syntax file. Default value is "final".

- Start (string): This feature is for mentioning the root component or rule for the syntax. The default value is "Start".

- baseFrequency (decimal): This feature is to mention the base frequency while playing. This basically relates to the frequency of the note "Sa". The default value is 360.0.

- msec (number): This feature is to mention the number of milli-seconds each note will be played for. The default value is 140.

- volume (decimal - 0.0 to 1.0): This feature is to mention the volume at which the notes will be played. The default value is 0.2.

- playFile (string): This feature is for the name of the .player file. It records the ongoings inside a player. There is no default value. If not provided the file won't be generated.

The following is a demonstration of how the declarations happen.

beatsPerCycle: 16;

numCycles: 10;

Range: ma_-ma*;

outFile: final;

Start: start;

baseFrequency: 440.00;

msec: 150;

volume: 0.5;

playFile: player_log

This is the part where the Paltas are declared. At the beginning we declare the Arohan and Avarohan in a block called sargam (octave). And then the series of paltas are declared. The declaration of Avarohan in the sargam block is optional. If it is not declared, it is internally assumed as the reverse of Arohan. The following is an example of how a typical scheme block looks like.

palta {

sargam {

arohan : Sa, ga, ma, dha, ni;

}

paltaUp -> 1232, 1.0 | 1123, 1.0 | 21243432, 1.0 | (123, 4), 1.0;

paltaDown -> (321, 4), 1.0;

}

Above is the scheme block for a Raag named Malkauns. Now Malkauns happens to be a Raag with Arohan and Avarohan having the same set of notes. So they were not separately mentioned. But for a Raag like Desh one would have to mention the Avarohan separately, like the following.

sargam {

arohan : Sa, Re, ma, Pa, Ni;

avarohan : Sa*, ni, Dha, Pa, ma, Ga, Re;

}

The next aspect to look at is the way the Paltas have been declared. Each Palta has a number of options, each with associated probability. Each time a Palta is called one of these options will be chosen. Now the options are also of two kinds:

- The first is a simple scheme

- The second is what is called a combinator scheme.

The combinator scheme is basically a set of numbers and a sample space, n, for which a simple scheme is built randomly every time that option is chosen.

Now let's look at a practical scenario to explain the working of Paltas. Lets take the Palta, paltaUp from the example of malkauns, and let's say, at a particular instant the third option is chosen, which is: [21243432, 1.0]. Now if this Palta is called on the note ga by the expression, paltaUp(ga), the sequence produced will be, [ga, Sa, ga, dha, ma, dha, ma, ga].

Now, as hinted earlier, here a Raag is assumed to be a Context Free Grammar (though this assumption may change later on) with a particular kind of predicate associated with each rule. These predicates are basically probabilities, which work as hints for the machine during derivation of the rules. The Raag on the other hand is basically an infinite set of sequences of notes (or viable notes) that is identified through the CFG. The rule space always starts with a "Start" symbol or rule. A typical example of a rule space is the following.

Start -> SaFirst, 1.0

| gaFirst, 1.0

| SaFirst*, 1.0;

SaFirst -> paltaUp(Sa)-gaFirst, 1.0

| paltaDown(Sa)-niFirst_, 1.0

| paltaUp(Sa)-maFirst, 0.5

| paltaDown(Sa)-dhaFirst_, 0.5;

gaFirst -> paltaUp(ga)-maFirst, 1.0

| paltaDown(ga)-SaFirst, 1.0

| paltaUp(ga)-dhaFirst, 0.5

| paltaDown(ga)-niFirst_, 0.5;

maFirst -> paltaDown(ma)-gaFirst, 1.0

| paltaUp(ma)-dhaFirst, 1.0

| paltaDown(ma)-niFirst, 0.5

| paltaUp(ma)-SaFirst, 0.5;

dhaFirst -> paltaUp(dha)-niFirst, 1.0

| paltaDown(dha)-maFirst, 1.0

| paltaUp(dha)-SaFirst*, 0.5

| paltaDown(dha)-gaFirst, 0.5;

niFirst -> paltaUp(ni)-SaFirst*, 1.0

| paltaDown(ni)-dhaFirst, 1.0

| paltaUp(ni)-gaFirst*, 0.5

| paltaDown(ni)-maFirst, 0.5;

Now an important feature to look at over here is, scaling (as I call it). Now, in practical situations, while playing a taan it is quite seldom that the artist restricts the notes within just an octave. So in that manner if we want to declare the syntax of a particular Raag we will have to hard code all the rules for the range we decide upon. That will make necessary a lot of repetitive coding as we may have to declare in some cases the same rule for three octaves seperately.

But that is not required as we have the feature of scaling. Here to mention the next octave or previous octave counterpart of a pre-defined or post-defined rule, we just need to append a "*" or an "_", respectively, to it. After using this feature we can mention the notes of the lowest and highest pitch in declarations' "range" parameter and the syntax will be scaled accordingly, as in the signature defined initially will be replicated without any loss across the mentioned range.

Although I think it is important to mention that this feature does not work the other way round. So if we declare a rule only in the higher octave, with a "*" appended, we can't expect that to be replicated in the lower octaves according to the mentioned range.

After the scaling happens in the directory of the ".raag" file, a file with ".syntax" extension is produced which contains the scaled version of the whole syntax or Raag. An example of the above syntax being scaled for the range: ma-ma*, is the following.

Start -> SaFirst, 1.0 | gaFirst, 1.0 | SaFirst*, 1.0;

SaFirst -> paltaUp(Sa)-gaFirst, 1.0 | paltaUp(Sa)-maFirst, 0.5 | paltaDown(Sa)-dhaFirst_, 0.5 | paltaDown(Sa)-niFirst_, 1.0;

gaFirst -> paltaDown(ga)-niFirst_, 0.5 | paltaUp(ga)-maFirst, 1.0 | paltaUp(ga)-dhaFirst, 0.5 | paltaDown(ga)-SaFirst, 1.0;

SaFirst* -> paltaUp(Sa*)-gaFirst*, 1.0 | paltaUp(Sa*)-maFirst*, 0.5 | paltaDown(Sa*)-niFirst, 1.0 | paltaDown(Sa*)-dhaFirst, 0.5;

maFirst -> paltaUp(ma)-SaFirst, 0.5 | paltaDown(ma)-gaFirst, 1.0 | paltaUp(ma)-dhaFirst, 1.0 | paltaDown(ma)-niFirst, 0.5;

dhaFirst_ -> paltaDown(dha_)-maFirst_, 1.0 | paltaUp(dha_)-SaFirst, 0.5 | paltaUp(dha_)-niFirst_, 1.0;

niFirst_ -> paltaUp(ni_)-gaFirst, 0.5 | paltaDown(ni_)-maFirst_, 0.5 | paltaDown(ni_)-dhaFirst_, 1.0 | paltaUp(ni_)-SaFirst, 1.0;

dhaFirst -> paltaUp(dha)-SaFirst*, 0.5 | paltaDown(dha)-maFirst, 1.0 | paltaUp(dha)-niFirst, 1.0 | paltaDown(dha)-gaFirst, 0.5;

gaFirst* -> paltaUp(ga*)-maFirst*, 1.0 | paltaDown(ga*)-niFirst, 0.5 | paltaDown(ga*)-SaFirst*, 1.0;

maFirst* -> paltaDown(ma*)-gaFirst*, 1.0 | paltaUp(ma*)-SaFirst*, 0.5;

niFirst -> paltaUp(ni)-SaFirst*, 1.0 | paltaDown(ni)-dhaFirst, 1.0 | paltaDown(ni)-maFirst, 0.5 | paltaUp(ni)-gaFirst*, 0.5;

maFirst_ -> paltaUp(ma_)-dhaFirst_, 1.0 | paltaDown(ma_)-niFirst_, 0.5;

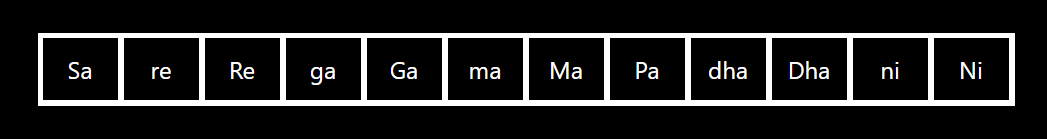

The final aspect of the scripting language is how we denote the musical notes. Now there are twelve notes in an octave. The following is a notation of each one of them in the ascending order of their frequency.

Now we are allowed to access only three octaves. So there is one whole octave before note "Sa" and one whole after note - "Ni".

The lower and higher octave counterparts of each note can be accessed in the same way scaling is achieved, by appending an "_" or a "*" to the individual notes.

The frequency of the note - "Sa" is the baseFrequency.

The frequencies of rest of the notes come form a geometric progression starting from the frequency of "Sa" with a mean ratio of .

And as the octave contains twelve notes, for any given note, the swar with * appended to that note is double its frequency while the _ appended one is half.

This is how the frequencies of all the notes for all the three octaves are resolved. These notes form the terminals or identifiers of a Raag.

The value of these terminals are determined by the value of the baseFrequency.