Model-based Reinforcement Learning Experiments

Introduction

This repository contains three different experiments considering the problem of an agent aiming to learn the dynamics of its environment from observed state transitions; i.e., to predict the next state of the environment given the current state and the action taken by the agent. From the local perspective of an agent, both partial observability and the presence of other agents acting concurrently complicates learning, since the environment appears non-stationary to the agent. The motivation for learning these dynamics models is to use them for model-based, deep reinforcement learning. The motivation for learning these dynamics models is to use them for model-based, deep reinforcement learning.

Why model-based RL

Model-free deep reinforcement learning algorithms have been shown to be capable of solving a wide range of robotic tasks. However, these algorithms typically require a very large number of samples to attain good performance, and can often only learn to solve a single task at a time. Model-based algorithms have been shown to provide more sample efficient and generalizable learning. In model-based deep reinforcement learning, a neural network learns a dynamics model, which predicts the feature values in the next state of the environment, and possibly the associated reward, given the current state and action. This dynamics model can then be used to simulate experiences, reducing the need to interact with the real environment whenever a new task has to be learned. These simulated experiences can be used, e.g., to train a Q-function (as done in the Dyna-Q framework), or a model-based controller that solves a variety of tasks using model predictive control (MPC).

In 4 the authors train a dynamics model using a dataset of fully observable state transitions, gathered by the agent by taking random actions in its environment. This dynamics model is then used to train model-based controllers that solve a number of locomotion tasks using orders of magnitude less experience than model-free algorithms. Moreover, the authors show how this model-based approach can be used to initialize a model-free learner.

Experiments

Learning a dynamics model under partial observability

In a Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDP), the true state

Learning the dynamics of the internal state of an agent

The dynamics of a video game, at the pixel level, are given by a sequence of video frames produced by a sequence of actions. The straight-forward approach for the model is to predict the next frame from a sequence of previous frames. While this approach has been shown to work 5, the idea in this experiment is a different one: instead of predicting the low-level pixel values the agent is trained to predict the dynamics of its own convolutional network, i.e. the dynamics of the learned filter responses. This approach draws its inspiration from image classification, where it is common practice to reuse the lower part of a pre-trained model for a new task in order to reduce training time and data compared to learning from scratch. Adapting this idea the filter-responses of the convolutional part of a standard RL agent are treated as observations with the hypothesis of being able to generalize over different types of video games.

Independent learning in multi-agent domains

In this setting, each agent can independently learn a model of the dynamics of the environment; the agent aims to predict its next observation given only its local observation and chosen action. The observations are the relative distances of objects or other agents in the environment. The task is to predict positions given a sequence of relative distances as the agent moves around in the environment.

Results

POMDP

Unlike 2, where a flickering video game is simulated by dropping complete frames randomly, in a sense a more general type of data corruption is considered. Each feature can be missing with a certain probability independently. The former notion of corruption would occur in the case of all features being dropped at the same time. But in our scenario, it can, for example, happen that velocity in one coordinate is missing but the other coordinates are not. Also, the agent knows which data is missing, but a preprocessing is applied before the data is fed to the neural network. Missing data is replaced by a MICE imputation process 3, where multiple samples from a fitted model are generated. So for each frame, multiple possible imputations are created and all fed to the network. Performance is measured as the coefficient of determination (R^2), which is 0 for random guessing and 1 for perfect predictions.

| Environment | Partial obs. | R^2 FFN | R^2 RNN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swimmer | 0.25 | 0.559 | 0.886 |

| 0.5 | 0.396 | 0.654 | |

| Hopper | 0.25 | 0.841 | 0.781 |

| 0.5 | 0.695 | 0.580 | |

| Bipedal Walker | 0.25 | 0.195 | 0.597 |

| 0.5 | 0.298 | 0.504 |

For the tested environments (Swimmer, Hopper, Bipedal Walker) the recurrent neural network (RNN) clearly outperformed the feed-forward network (FFN) and was even under pretty severe imputation able to predict the next step in the movement trajectory.

Filter response prediction learning

An instance of Kera-RL's Deep Q Network (DQN) agent was trained in OpenAI's Gym environments. The training for Pong succeeded, but the network failed to predict filter responses for Breakout and Seaquest at all. The numbers are therefore only listed for Pong.

| DQN Agent samples | R^2 FFN | R^2 RNN |

|---|---|---|

| 250k | 0.074 | 0.186 |

| 2.75M | 1.000 | 1.000 |

What seems to be confirmed is the expected performance gain for a recurrent architecture. Also, interesting to note is the difference in learnability for the number of samples the base DQN agent was trained on. After a mere 250,000 samples, the learned filters presumably don't produce a well-defined signal from the input images. Thus there is not enough structure in the responses that it is possible to learn. Unfortunately, for the visually more complex games Breakout and Seaquest, even the RNN wasn't able to capture the structure of the game.

UPDATE (August '18): Recently I came across a similar approach 8, where the predictability of filter responses is used as an indicator for previously unseen states. The agent is then incentivized to explore the environment by achieving rewards for reaching states, which are not well predicted. Although the filters themselves are trained on the filter response prediction task - jointly with inferring the action underlying the observed state transition, which avoids the trivial solution - the MSE is comparable to the one achieved here (4x10^-4 vs. 2x10^-3). The resulting mean absolute percentage error is therefore also quite high (4x10^4).

Multi-agent domains

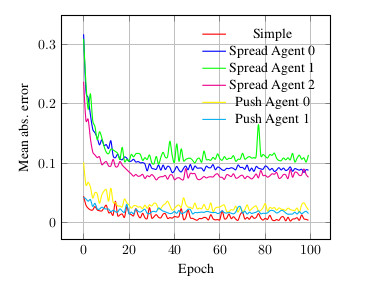

The multi-agent environments 1 feature a continuous observation and a discrete action space. The environments are as follows:

- Simple: Single agent sees landmark position, rewarded based on how close it gets to a landmark.

- Push: 1 agent, 1 adversary, 1 landmark. Agent is rewarded based on distance to landmark. Adversary is rewarded if it is close to the landmark and if the agent is far from the landmark. So the adversary learns to push agent away from the landmark.

- Spread: N agents, N landmarks. Agents are rewarded based on how far any agent is from each landmark. Agents are penalized if they collide with other agents. So, agents have to learn to cover all the landmarks while avoiding collisions.

Conclusion and future work

Handling partial observability seems to extend well to scenario of partial frame drops, which is also a realistic setting in robotic tasks with faulty sensors. Dynamics learning for convolutinal filter prediction might benefit from the stacking of LSTM cells, which is a direction to explore in the future. But still transferable skills in RL, even if only considering different types of video games, is a challenging task and subject to current research 6. In the multi-agent environment one of the main aspects hasn't been touched upon. While in the current approach the agents only observe the positional information coming from the environment, the ability to communicate is left aside. As language has been shown to drive transfer in RL 7 this is another promising directions.

Running the code

Either run MDP_learning.ipynb or run

MDP_learning/single_agent/dynamics_learning.pyfor POMDP learningMDP_learning/from_pixels/dqn_kerasrl_modellearn.pyfor CNN filter response predictionMDP_learning/multi_agent/multi.pyfor the multi agent setting

And grab a cup of tea... It might take a while.

References

[2]: Matthew Hausknecht and Peter Stone, "Deep recurrent Q-learning for partially observable MDPs"

[3] Roderick JA Little and Donald B Rubin, "Statistical analysis with missing data"

[4] Anusha Nagabandi, Gregory Kahn, Ronald S Fearing, and Sergey Levine, "Neural network dynamics for model-based deep reinforcement learning with model-free fine-tuning"

[5] Junhyuk Oh, Xiaoxiao Guo, Honglak Lee, Richard Lewis, and Satinder Singh, "Action-Conditional Video Prediction using Deep Networks in Atari Games"

[6] http://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2017/07/18/learning-to-learn/

[7] Karthik Narasimhan, Regina Barzilay, and Tommi Jaakkola, "Deep Transfer in Reinforcement Learning by Language Grounding"

[8] Deepak Pathak, Pulkit Agrawal, Alexei A. Efros, Trevor Darrell, " Curiosity-driven Exploration by Self-supervised Prediction"