SquidTasks 0.2.0

[TOC]

Overview of Squid::Tasks

Squid::Tasks is a header-only library consisting of several top-level headers within the include directory.

Task.h- Task-handles and standard awaiters [REQUIRED]TaskManager.h - Manager that runs and resumes a collection of tasksTokenList.h- Data structure for tracking decentralized state across multiple tasksFunctionGuard.h- Scope guard that calls a function as it leaves scopeTaskFSM.h- Finite state machine that implements states using task factories

Sample projects can be found under the @c /samples directory.

Integrating Squid::Tasks

Including the Headers

To integrate the Squid::Tasks library into your project, we recommend first copying the entire include directory into your project. You must then add the path of the include directory to the list of include directories in your project.

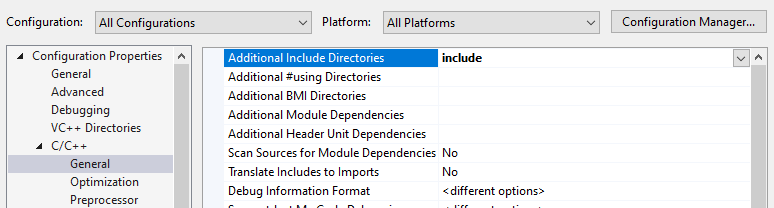

In Visual Studio, this is done by right-clicking your project and selecting Properties. Then navigate to Configuration Properties -> C/C++ -> General, and add the the path to the include directory to “Additional Include Directories”.

Enabling Coroutines for C++14/17 (skip this step if using C++20)

C++ coroutines were only formally added to the standard with C++20. In order to use them with earlier standards (C++14 or C++17), you must enable coroutines using a special compiler-specific compile flag.

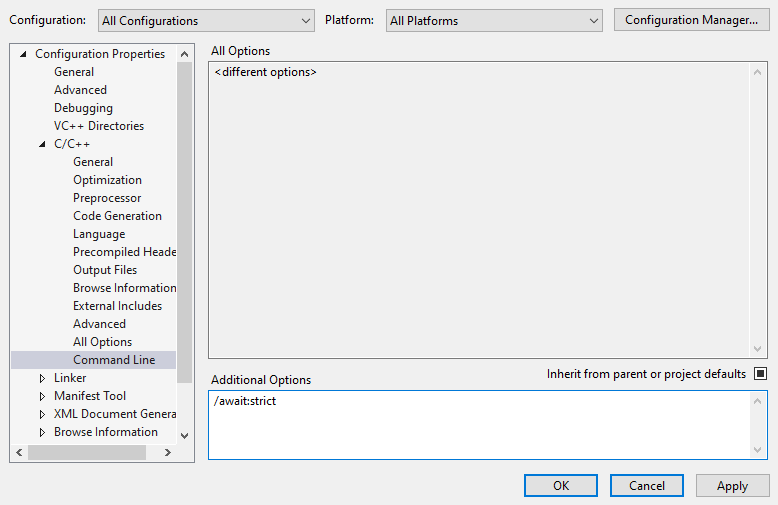

In Visual Studio, this is done by right-clicking your project and selecting Properties. Then navigate to Configuration Properties -> C/C++ -> Command Line, and add /await to “Additional Options”.

(IMPORTANT NOTE: If you are using C++17, you should instead add /await:strict to "Additional Options", as shown below.)

If you are using Clang, you will need to add -fcoroutines-ts to your compiler command-line compilation parameters.

If you are using the Clang Platform Toolset from within Visual Studio, you will need to add -Xclang -fcoroutines-ts to your compiler command-line compilation parameters.

Configure Squid::Tasks with TasksConfig.h

The Squid::Tasks library can be configured in a variety of important ways. This is done by enabling and disabling preprocessor values within the include/TasksConfig.h file:

- SQUID_ENABLE_TASK_DEBUG: Enables Task debug callstack tracking and debug names via Task::GetDebugStack() and Task::GetDebugName()

- SQUID_ENABLE_DOUBLE_PRECISION_TIME: Switches time representation from 32-bit single-precision floats to 64-bit double-precision floats

- SQUID_ENABLE_NAMESPACE: Enables a Squid:: namespace around all classes in the Squid::Tasks library

- SQUID_USE_EXCEPTIONS: Enables experimental (largely-untested) exception-handling, and replaces all asserts with runtime_error exceptions

- SQUID_ENABLE_GLOBAL_TIME: Enables global time support (alleviating the need to specify a time stream for time-sensitive awaiters) [see Appendix A for more details]

An Example First Task

To get started using Squid::Tasks, the first step is to write and execute your first task from within your project. Many modern C++ game engines feature some sort of "actor" class - a game entity that exists within the scene and is updated each frame. Our example code assume this class exists, but the same principles will apply for projects that are written under a different paradigm.

The first step is to identify an actor class that would benefit from coroutine support, such as an enemy actor. Here is an example Enemy class from a hypothetical 2D game:

class Enemy : public Actor

{

public:

void SetRotation(float in_degrees); // Set the rotation of the enemy

float GetRotation() const; // Get the rotation of the enemy

void SetPosition(Vec2f in_pos); // Set the position of the enemy

Vec2f GetPosition() const; // Get the position of th enemy

void MoveToward(Vec2f in_pos, float in_speed, float in_dt) const; // Move toward a target position at a given speed

void FireProjectileAt(Vec2f in_pos); // Fire a simple projectile to a target position

std::shared_ptr<Player> GetPlayer() const; // Get the location of the player actor

float GameTime() const; // Get the current game time (in seconds)

float DeltaTime() const; // Get the current frame's delta-time (in seconds)

virtual void OnInitialize() override // Automatically called when this enemy enters the scene

{

Actor::OnInitialize(); // Call the base Actor function

}

virtual void Tick(float in_dt) override // Automatically called every frame

{

Actor::Tick(in_dt); // Call the base Actor function

}

virtual void OnDestroy() override // Automatically called when this enemy leaves the scene

{

Actor::OnDestroy(); // Call the base Actor function

}

};We want to try writing a simple enemy AI using Squid::Tasks. Conventionally, the Tick() function would be responsible for performing all AI logic calculations, so we will use that as the entry-point into our first task coroutine. First, we will create a TaskManager as a private member m_taskMgr. Then, we call m_taskMgr.Update() from within Tick(). Lastly, we need to make sure all of tasks stop running as soon as the enemy leaves the scene, so we call m_taskMgr.KillAllTasks() from within OnDestroy().

class Enemy : public Actor

{

public:

// ...

virtual void Tick(float in_dt) override // Automatically called every frame

{

Actor::Tick(in_dt); // Call the base Actor function

m_taskMgr.Update(); // Resume all active tasks once per tick

}

virtual void OnDestroy() override // Automatically called when this enemy leaves the scene

{

m_taskMgr.KillAllTasks(); // Kill all active tasks when we leave the scene

Actor::OnDestroy(); // Call the base Actor function

}

protected:

TaskManage m_taskMgr;

};Now that we have the task manager hooked up, we can write and run our first task. Let's make our first task very simple, and just have it print out a string and then terminate. To create a task, we simply write a member function with returns type Task<>, and make sure to use at least one co_await or co_return keyword within the function body. This tells the compiler to compile the function as a coroutine with Task<> as the handle type for the coroutine.

class Enemy : public Actor

{

public:

// ...

virtual void OnInitialize() override // Automatically called when this enemy enters the scene

{

Actor::OnInitialize(); // Call the base Actor function

m_taskMgr.RunManaged(ManageEnemyAI()); // Run our task as a fire-and-forget "managed task"

}

// ...

Task<> ManageEnemyAI()

{

TASK_NAME(__FUNCTION__); // Gives the task a name for debugging purposes

printf("Hello, enemy AI!\n");

co_return; // Return from this task

}

};With these changes, any enemy instance that enters the scene will print "Hello, enemy AI!". Note that we actually run the task from within OnInitialize(). This line is what actually instantiates the task and tells the task manager to update it every frame. Now that we have the complete scaffolding in, we can try to write an actual enemy behavior. Let's try writing a simple chase AI that chases the player if they get too close to the enemy.

class Enemy : public Actor

{

public:

// ...

Task<> ManageEnemyAI()

{

TASK_NAME(__FUNCTION__); // Gives the task a name for debugging purposes

while(true) // This "infinite loop" means this task should run for the enemy's lifetime

{

// Wait until player gets within a 100-pixel radius

co_await WaitUntil([&] {

return Distance(GetPlayer()->GetPosition(), GetPosition()) < 100.0f;

});

// Move toward the player as long as they are within a 100-pixel radius

while(Distance(GetPlayer()->GetPosition(), GetPosition()) < 100.0f)

{

MoveToward(GetPlayer()->GetPosition(), 100.0f, DeltaTime());

co_await Suspend();

}

// Cool-down for 2 seconds before following again

co_await WaitSeconds(2.0f, GameTime());

}

}

};Our chase enemy AI is complete! One advantage of coroutines is that they tend to be fairly straightforward to read, so hopefully you can guess at what some of the above logic means. Regardless, let's break down how this works. The first thing we do is create a while(true) loop around our logic. This is a common coroutine pattern, but it can be confusing the first time you see it. In a normal function, an infinite loop would result in the thread soft-locking. However, in coroutines this pattern essentially means "this coroutine will run for the lifetime of the object running it", which is the desired behavior for our enemy AI task.

The next thing we see is the new co_await keyword. The co_await <awaiter> expression, when evaluated, will suspend the current task until the awaiter is ready to be resumed again. In this example we use 3 of the most versatile and powerful awaiters in Squid::Tasks:

- Suspend() -> Waits until the next time the task is resumed (usually a single frame)

- WaitSeconds() -> Waits until N seconds have passed in a given time-stream

- WaitUntil() -> Waits until a given function returns true

With these 3 awaiters, it is possible to implement enormously complex state machines with relatively straightforward code. (To learn about the other awaiters that come with Squid::Tasks, refer to the \ref Awaiters documentation.)

Next Steps

Hopefully, this brief tutorial has given you an outline of the steps required to integrate coroutines into your own projects. From here, we recommend exploring the "GeneriQuest" sample project under samples/Sample_TextGame. It demonstrates both simple and complex applications of coroutines in a simple text-based game example.

This is the end of the tutorial documentation (for now)! If you made it this far, feel free to write to [tim at giantsquidstudios.com] to let us know any ways in which our documentation could have been more useful for you in learning to use Squid::Tasks!

Appendices

APPENDIX A: Enabling Global Time Support

Every game project has its own method of updating and measuring game time. Most games feature multiple different "time-streams", such as "game time", "real time", "editor time", "paused time", "audio time", etc... Because of this, the Squid::Tasks library requires each time-sensitive awaiter (e.g. WaitSeconds(), Timeout(), etc) to be presented with a time-stream function that returns the current time in the desired time-stream. By convention, these time-streams are passed as functions into the final argument of time-sensitive awaiters.

A final (optional) step of integrating Squid::Tasks is to enable global time support and implement a global Squid::GetTime() function.

For less-complex projects it can be desirable to default to a "global time-stream" that removes the requirement to explicitly pass a time-stream function into time-sensitive awaiters. To enable this functionality, the user must set SQUID_ENABLE_GLOBAL_TIME in TasksConfig.h and implement a special function called Squid::GetTime(). Failure to define this function will result in a linker error.

The Squid::GetTime() function should return a floating-point value representing the number of seconds since the program started running. Here is an example Squid::GetTime() function implementation from within the main.cpp file of a sample project:

NAMESPACE_SQUID_BEGIN

tTaskTime GetTime()

{

return (tTaskTime)TimeSystem::GetTime();

}

NAMESPACE_SQUID_ENDIt is recommended to save off the current time value at the start of each game frame, returning that saved value from within Squid::GetTime(). The reason for this is that, within a single frame, you likely want all of the tasks to behave as if they are updating at the same time. By providing the same exact time value to all Tasks that are resumed within a given update, the software is more likely to behave in a stable and predictable manner.