How powerful can an ensemble of linear models be?

How an ensemble of linear models got in the top 6% of Mercari price prediction challenge leaderboard on Kaggle.

With the rapid growth of deep learning algorithms in recent years, today they have become a state of the art in AI. And this makes me wonder if the traditional and old school machine learning techniques like Linear Regression, Support Vector Machines, etc are still decent enough that they can go head to head with deep learning techniques? To look over the capabilities of these often overlooked machine learning techniques I will be solving a Kaggle competition problem using only traditional machine learning techniques (no neural networks).

Note: I’ll be using python 3.7 for this project.

Bird’s eye view of the blog-

The project is divided into 6 major steps-

-

Business problem and evaluation metrics

-

About the data

-

Exploratory Data Analysis

-

Data preprocessing

-

Modeling

-

Obtaining scores from Kaggle leaderboard.

Business problem and Evaluation metrics

It can be hard to know how much something’s really worth. Small details can mean big differences in pricing. For example, one of these sweaters cost $335 and the other cost $9.99. Can you guess which one’s which?

Product pricing gets even harder at scale, considering just how many products are sold online. Clothing has strong seasonal pricing trends and is heavily influenced by brand names, while electronics have fluctuating prices based on product specifications. Mercari, Japan’s biggest community-powered shopping app, knows this problem deeply. They’d like to offer pricing suggestions to sellers, but this is tough because their sellers are enabled to put just about anything, or any bundle of things, on Mercari’s marketplace. In this competition, we need to build an algorithm that automatically suggests the right product prices. We’ll be provided with text descriptions of products, and features including details like product category name, brand name, and item condition.

The evaluation metric for this competition is Root Mean Squared Logarithmic Error. The RMSLE is calculated as:

Where: ϵ is the RMSLE value (score) n is the total number of observations in the (public/private) data set, pi is the prediction of price, ai is the actual sale price for i. log(x) is the natural logarithm of x

Note that, because of the public nature of this data, this competition is a “Kernels Only” competition. So, we need to build a code that executes within an hour on a machine with 16 GB RAM and 4 CPUs.

About the data

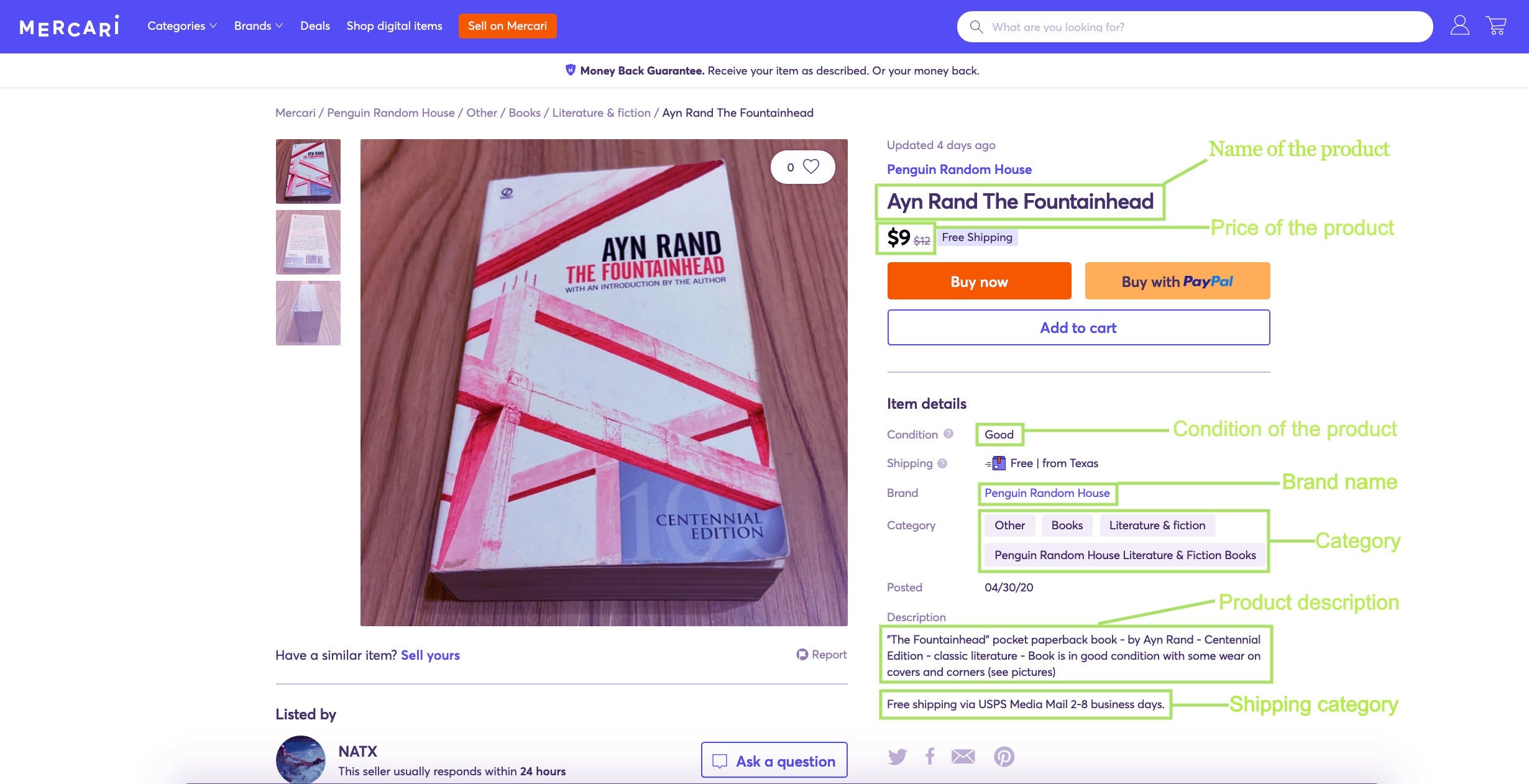

The data we’ll be using is provided by Mercari and can be found on Kaggle using this link. The data lists details about products from the Mercari website. Let’s check out one of the products from the website and how it is described in the dataset.

The dataset has 8 features:

-

Train_id/Test_id: Every item in the dataset has a unique item id. This will be used while submitting the predicted prices.

-

**Name: **Represents the name of the product, it is in string format. For the above product, the name is ‘Ayn Rand The Fountainhead’

-

**Item condition: **A number provided by the seller that denotes the condition of the item. It can take a value between 1 and 5. In our case, the condition of the product is ‘*good’ *so it’ll be denoted by 4 in the dataset.

-

Category name: Represents the category of the item. For the above item, the category mentioned in the dataset is *‘other/books/Literature & Fiction’ *and this feature is also of datatype string.

-

Brand name: Represents the name of the brand the item belongs to. For the above product, the brand-name is ‘Penguin Random House’.

-

Price: Represents the price of the item, in our case, this will be the target value that we need to predict. The unit is USD. For the above product, the price provided is ‘$9’.

-

Shipping: A number that represents the type of shipping available on the product. Shipping will be 1 if the shipping fee is paid by the seller and 0 if the fee is paid by the buyer. For the above product, the shipping is free so in the dataset, this feature will be 1.

-

Item description: The full description of the item. For the above product, the description says, *“The Fountainhead” pocket paperback book — by Ayn Rand — Centennial Edition — classic literature — Book is in good condition with some wear on covers and corners (see pictures)”. *This feature comes already in a preprocessed form in the provided dataset.

Let’s import the data using pandas and check the first 5 entries.

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv('train.tsv', sep='\t')

df_test = pd.read_csv('test.tsv', sep='\t')

data.head()

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

In this section, we’ll be exploring and analyzing the data in depth. We’ll be covering the data feature by feature.

Price

This is the target feature that we need to predict using the information about the product in the form of other features. Let’s check out the statistical summary of this feature using describe()

data['price'].describe()

- There are about 1.48 million products in the dataset. The costliest product is priced at $ 2009, the cheapest product is priced at $ 3 whereas the mean price is $ 26.75

Now we’ll take a look at the histogram of the prices. Here, I’ve used the number of bins as 200.

plt.hist(data['price'], bins=200)

plt.xlabel('price')

plt.ylabel('frequency')

plt.title('histogram of price')

plt.show()

- We can observe that the distribution follows a power-law distribution, to fix that, and to make it kind of Gaussian distribution, let’s convert the values to the log form i.e. we’ll be replacing the price values with log(price+1).

We are converting the prices to Normal distribution as it is one of the most well-known distributions in statistics because it fits many natural phenomena and this makes it one of the most easily interpretable distributions that we can do analysis on. Another reason for transforming the data into a normal distribution is that the variance in price is reduced and most of the points are centered around the mean which makes the price prediction much easier for the model.

I’ve already converted the data into a log form. Here is the histogram of the log(price+1).

plt.hist(data['price_log'], bins=20)

plt.xlabel('log(price + 1)')

plt.ylabel('frequency')

plt.title('histogram of log of price')

plt.show()

-

We can observe that the distribution is much more interpretable now and tries to follow a Normal distribution.

-

Also, notice how most of the points are centered around the mean (the mean is somewhere near 3).

item_condition_id

This is a categorical feature that denotes the condition of the item. Let’s check out more about it using value_counts()

data['item_condition_id'].value_counts()

- The output tells us that this feature can take up 5 values between 1 and 5, and the number of items with that particular condition is mentioned next to it.

Let’s look at the bar-graph of this feature

sns.barplot(x=data['item_condition_id'].value_counts().keys(),

y=data['item_condition_id'].value_counts())

plt.xlabel('item condition type')

plt.ylabel('number of products')

plt.title('bar graph of "item condition type"')

plt.show()

- We can see that a majority of items have a condition id of 1, and only very few items have a condition id of 5.

Now let’s compare the price distribution of products with different item_condition_id

- We can see that the price distributions of items having different item_condition_id are very similar.

Let’s check out the boxplot and violin plot of the price distribution of products with different item_condition_id.

# plotting box-plot

sns.boxplot(x='item_condition_id', y='price_log', data=data)

plt.show()

# plotting violin plot

sns.violinplot(x='item_condition_id', y='price_log', data=data)

plt.show()

The boxplot and violin plots also tell us that the price distributions of items with different item_condition_id are not so different, also the distributions are a bit right-skewed. Products with item_condition_id = 5 have the highest median price whereas products with item_condition_id = 4 have the lowest median price. Most of the products have a price in the range of 1.5 and 5.2

Category name

This is a text type data that tells us about the category of the product. Let’s check out the statistical summary of the feature category name-

data['category_name'].describe()

These are string type features that are actually 3 sub-categories joined into 1. Let’s consider the most frequently occurring category name feature ‘Women/Athletic Apparel/Pants, Tights, Leggings’ as mentioned in the above description. It can be broken down into 3 sub-categories:

-

sub-category_1: ‘Women’

-

sub-category_2: ‘Athletic Apparel’

-

sub-category_3: ‘Pants, Tights, Leggings’ To make the visualization for this feature easy, I’ll consider this feature sub-category wise. Let’s divided the data sub-category wise.

this is to divide the category_name feature into 3 sub categories

from tqdm import tqdm_notebook sub_category_1 = [] sub_category_2 = [] sub_category_3 = []

for feature in tqdm_notebook(data['category_name'].values): fs = feature.split('/') a,b,c = fs[0], fs[1], ' '.join(fs[2:]) sub_category_1.append(a) sub_category_2.append(b) sub_category_3.append(c)

data['sub_category_1'] = sub_category_1 data['sub_category_2'] = sub_category_2 data['sub_category_3'] = sub_category_3

Sub-category_1

Let’s check the statistical description:

data['sub_category_1'].describe()

- There are around 1.4M of these in our data, that can take 11 distinct values. The most frequent of these are Women.

Let’s plot the bar graph of sub-category 1

sns.barplot(x=data['sub_category_1'].value_counts().keys(), y=data['sub_category_1'].value_counts())

plt.ylabel('number of products')

locs, labels = plt.xticks()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=90)

plt.title('bar-plot of sub_category_1')

plt.show()

-

We can see that most of the items have sub_category_1 as ‘women’ and the least items have ‘Sports & Outdoors’.

-

Note that items with no sub_category_1 defined are denoted with ‘no label’.

Let’s check the distribution of sub_category_1 and log of price

sns.FacetGrid(data, hue="sub_category_1", height=5).map(sns.distplot, 'price_log').add_legend();

plt.title('comparing the log of price distribution of products with

sub_category_1\n')

plt.ylabel('PDF of log of price')

plt.show()

-

We can see that most of the distributions are right-skewed with a little difference.

-

The sub-category ‘handmade’ is slightly distinguishable as we can see some products in this category with log(price) of less than 2

Now let’s take a look at the violin plots of sub_category_1

- Looking at the violin plot, we can say that the distribution of items with ‘men’ as sub_category_1 tends to be on the pricier end whereas items with ‘handmade’ as sub_category_1 tend to be on the economical end.

Sub_category_2

Let’s check the statistical description of sub_category_2:

data['sub_category_2'].describe()

- sub_category_2 has 114 distinct values, let’s analyze the top 20 categories of sub_category_2.

Bar graph of the top 20 categories in sub_category_2

plt.figure(figsize=(12,8))

sns.barplot(x=data['sub_category_2'].value_counts().keys()[:20],

y=data['sub_category_2'].value_counts()[:20])

plt.ylabel('number of products')

locs, labels = plt.xticks()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=90)

plt.title('bar-plot of top 20 sub_category_2')

plt.show()

- We can see that most of the items have sub_category_2 as ‘authentic apparel’ followed by ‘Makeup’ and then ‘Tops & Blouses’.

Sub_category_3

Let’s check the statistical description of sub_category_3:

- sub_category_3 has 865 distinct values, let’s analyze the histogram of the top 20 categories of sub_category_3.

- We can see that most of the items have sub_category_3 as ‘Pants, Tights, Leggings’ followed by ‘Other’ and ‘Face’.

Brand name

This is another text type feature that denotes the brand the product belongs to. Let’s check out the statistical summary of the feature brand_name.

- Here, we can see that there are a total of 4089 distinct brand names.

Let’s check the histogram of the top 20 brands

plt.figure(figsize=(12,8))

sns.barplot(x=data['brand_name'].value_counts().keys()[:20],

y=data['brand_name'].value_counts()[:20])

plt.ylabel('number of products')

locs, labels = plt.xticks()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=50)

plt.title('bar-plot of top 20 brands (including products with

unknown brand)')

plt.show()

-

Note that here, ‘unknown’ represents the item with no brand specified.

-

PINK, Nike, and Victoria’s Secret are the top 3 brands with most items on the website.

Let’s see the bar-plot of the top 20 brands with their mean product price.

plt.figure(figsize=(12,8))

sns.barplot(x=df['brand_name'].values[:20],

y=df['price'].values[:20])

plt.ylabel('average price of products')

locs, labels = plt.xticks()

plt.setp(labels, rotation=50)

plt.title('bar-plot of top 20 brands with their mean product price')

plt.show()

Let’s see the bar-plot of the top 20 brands with maximum product price

Shipping

This is a numerical categorical data type that can take 2 values, 0s or 1s Let’s check out its statistical description.

data['shipping'].value_counts()

- There are about 22% more items with shipping as 0 than 1.

Let’s compare the log of price distribution of products with different shipping.

-

We can see that the log of price distribution of items with different shipping has a slight variance.

-

The products with shipping as 1 tend to have a lower price.

item_description (text)

This is a text type feature that describes the product. Let’s take a look at some of these.

data['item_description']

- We can see that there are a total of 1482535 of these.

We’ll be using this feature as is after performing some NLP techniques which will be discussed later in this blog. Another thing that we can do with this feature is, calculate it’s word-length i.e. the number of words this feature contains for each product and do some analysis on that. Let’s check the statistical summary of the word_length of the item description.

data['item_description_word_length'].describe()

- We can see that the longest description has 245 words and the shortest has no words. On average the words are around 25

Let’s plot the histogram of item_description_word_length,

plt.hist(data['item_description_word_length'], bins=200)

plt.xlabel('item_description_word_length')

plt.ylabel('frequency')

plt.title('histogram of item_description_word_length')

plt.show()

-

We can see that the histogram of word length follows a power-law distribution.

-

I’ve used 200 bins for this histogram.

Let’s try to convert this into a Normal distribution by taking the log of the word length. Here is what the distribution looks like.

plt.hist(data['log_item_description_word_length'])

plt.xlabel('log(item_description_word_length + 1)')

plt.ylabel('frequency')

plt.title('histogram of log of item_description_word_length')

plt.show()

-

We can see that this feature tries to follow a Normal distribution.

-

Most of the items have a word length between 5 and 20. (values obtained from antilog).

-

We can use this as a feature for modeling.

Now let’s see how the log(item_word_length) affects the price of the item

-

We can see that the log of price increases as the item_word_length goes from 0 to 50 but then the prices tend to come down except the spike that we can observe near word length of around 190.

-

Also, the prices are much more volatile for word length more than 100.

Name of the product

Finally, let’s check out the last feature that is the name of the product. This is also a text type feature and we’ll be performing NLP on it later but first, let’s do some analysis on it by plotting the histogram of the number of words in the ‘name’ feature.

plt.hist(data['name_length'])

plt.xlabel('name_length')

plt.ylabel('frequency')

plt.title('histogram of name_length')

plt.show()

- The distribution is visibly left-skewed and maximum items have a name length of about 25.

Let’s see how the prices vary with the number of words in the product’s name.

df = data.groupby('name_length')['price_log'].mean().reset_index()

plt.figure(figsize=(12,8))

sns.relplot(x="name_length", y="price_log", kind="line", data=df)

plt.show()

-

Note that I’m using the log of prices instead of the actual prices.

-

We can see that the distribution is much linear for name_length values between 10 and 38 and then there’s a sharp drop and rise.

Data preprocessing

In this step, we’ll be cleaning the data and make it ready for modeling. Remember that we have 6 features out of which, we have:

- 4 text features: Name, description, brand name, and category

- 2 categorical features: shipping and the item_condition_id

Let’s start by cleaning the text features and for that, we’ll define some functions-

import re

def decontracted(phrase):

# specific

phrase = re.sub(r"won't", "will not", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"can\'t", "can not", phrase)

# general

phrase = re.sub(r"n\'t", "not", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'re", " are", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'s", " is", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'d", " would", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'ll", " will", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'t", " not", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'ve", " have", phrase)

phrase = re.sub(r"\'m", " am", phrase)

return phrase

The function works by decontracting words like “we’ll” to “we will”, “can’t” to “cannot”, “we’re” to “we are” etc. This step is necessary because we do not want our model to treat phrases like “we’re” and “we are” differently.

stopwords= ['i', 'me', 'my', 'myself', 'we', 'our', 'ours', 'ourselves', 'you', "you're", "you've","you'll", "you'd", 'your', 'yours', 'yourself', 'yourselves', 'he', 'him', 'his', 'himself', 'she', "she's", 'her', 'hers', 'herself', 'it', "it's", 'its', 'itself', 'they', 'them', 'their','theirs', 'themselves', 'what', 'which', 'who', 'whom', 'this', 'that', "that'll", 'these', 'those', 'am', 'is', 'are', 'was', 'were', 'be', 'been', 'being', 'have', 'has', 'had', 'having', 'do', 'does', 'did', 'doing', 'a', 'an', 'the', 'and', 'but', 'if', 'or', 'because', 'as', 'until', 'while', 'of', 'at', 'by', 'for', 'with', 'about', 'against', 'between', 'into', 'through', 'during', 'before', 'after','above', 'below', 'to', 'from', 'up', 'down', 'in','out','on','off', 'over', 'under', 'again', 'further','then', 'once', 'here', 'there', 'when', 'where', 'why','how','all', 'any', 'both', 'each', 'few', 'more','most', 'other', 'some', 'such', 'only', 'own', 'same', 'so','than', 'too', 'very', 's', 't', 'can', 'will', 'just','don',"don't",'should',"should've", 'now', 'd', 'll', 'm', 'o','re','ve','y','ain','aren',"aren't",'couldn',"couldn't",'didn',"didn't", 'doesn', "doesn't", 'hadn',"hadn't", 'hasn', "hasn't", 'haven', "haven't", 'isn', "isn't",'ma', 'mightn', "mightn't", 'mustn',"mustn't", 'needn', "needn't",'shan',"shan't",'shouldn',"shouldn't", 'wasn', "wasn't", 'weren', "weren't", 'won', "won't", 'wouldn', "wouldn't", '•', '❤', '✨', '$', '❌','♡', '☆', '✔', '⭐','✅', '⚡', '‼', '—', '▪', '❗', '■', '●', '➡','⛔', '♦', '〰', '×', '⚠', '°', '♥', '★', '®', '·','☺','–','➖','✴', '❣', '⚫', '✳', '➕', '™', 'ᴇ', '》', '✖', '▫', '¤','⬆', '⃣', 'ᴀ', '❇', 'ᴏ', '《', '☞', '❄', '»', 'ô', '❎', 'ɴ', '⭕', 'ᴛ','◇', 'ɪ', '½', 'ʀ', '❥', '⚜', '⋆', '⏺', '❕', 'ꕥ', ':', '◆', '✽','…', '☑', '︎', '═', '▶', '⬇', 'ʟ', '!', '✈', '�', '☀', 'ғ']

In the above code block, I’ve defined a list containing the stop words. Stop words are words that do not add much semantic or literal meaning to sentences. Most of these are contracted representations of words or not so important words like ‘a’, ‘at’, ‘for’ etc, and symbols.

Now we’ll define a function that takes the sentences, and uses the deconcatenated function and stopwords list to clean and return processed text.

from tqdm import tqdm_notebook

def preprocess_text(text_data):

preprocessed_text = []

# tqdm is for printing the status bar

for sentence in tqdm_notebook(text_data):

sent = decontracted(sentence)

sent = sent.replace('\\r', ' ')

sent = sent.replace('\\n', ' ')

sent = sent.replace('\\"', ' ')

sent = re.sub('[^A-Za-z0-9]+', ' ', sent)

sent = ' '.join(e for e in sent.split() if e.lower() not in

stopwords)

preprocessed_text.append(sent.lower().strip())

return preprocessed_text

Time to clean our text data using preprocess_text() function.

df['name'] = df['name'].fillna('') + ' ' +

df['brand_name'].fillna('')

df['name'] = preprocess_text(df.name.values)

df['text'] = (df['item_description'].fillna('')+

' ' + df['category_name'].fillna(''))

df['text'] = preprocess_text(df.text.values)

df_test['name'] = df_test['name'].fillna('') + ' '

+ df_test['brand_name'].fillna('')

df_test['text'] = (df_test['item_description'].fillna('') + ' '

+ df_test['category_name'].fillna(''))

Note that the df[‘name’] column contains both ‘name’ and ‘brand_name’ features concatenated and preprocessed, similarly df[‘text’] feature contains ‘item_description’ and ‘category_name’ features concatenated and preprocessed.

Let’s proceed to the further processes but before that, we need to split the data into train and cross-validation sets. Also, we’ll be converting the target values i.e. the prices into log form so that they are normally distributed and the RMSLE(root mean squared log error) is easy to compute.

df = df[['name', 'text', 'shipping', 'item_condition_id']]

X_test = df_test[['name', 'text', 'shipping', 'item_condition_id']]

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

y_scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train, X_cv, y_train, y_cv = train_test_split(df, y,

test_size=0.05, random_state=42)

y_train_std =

y_scaler.fit_transform(np.log1p(y_train.values.reshape(-1, 1)))

Now it’s time to convert these preprocessed text features into a numerical representation. I’ll be using TF-IDF vectorizer for this process. We’ll start with the feature ‘name’

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer as Tfidf

tfidf = Tfidf(max_features=350000, token_pattern='\w+', ngram_range=(1,2)) # using only top 350000 tf-idf features (with bi-grams).

X_tr_name = tfidf.fit_transform(X_train['name'])

X_cv_name = tfidf.transform(X_cv['name'])

X_test_name = tfidf.transform(X_test['name'])

Next comes the feature ‘text’

tfidf = Tfidf(max_features=350000, token_pattern='\w+', ngram_range=(1,3)) # using only top 350000 tf-idf features (with tri-grams).

X_tr_text = tfidf.fit_transform(X_train['text'])

X_cv_text = tfidf.transform(X_cv['text'])

X_test_text = tfidf.transform(X_test['text'])

Let’s also process the remaining categorical features starting with ‘shipping’ since this feature takes only 2 values 0 and 1, we do not need to perform some special kind of encoding for these, let’s keep them as they are.

from scipy import sparse

X_tr_ship =

sparse.csr_matrix(X_train['shipping'].values.reshape(-1,1))

X_cv_ship = sparse.csr_matrix(X_cv['shipping'].values.reshape(-1,1))

X_test_ship =

sparse.csr_matrix(X_test['shipping'].values.reshape(-1,1))

The second categorical feature that also happens to be an ordinal feature is ‘item_condition_id’. Remember these can take 5 integer values (1–5) so we’ll also keep these as they are.

X_tr_condition =

sparse.csr_matrix(X_train['item_condition_id'].values.reshape(-1,1)

- 1.)

X_cv_condition =

sparse.csr_matrix(X_cv['item_condition_id'].values.reshape(-1,1)

- 1.)

X_test_condition =

sparse.csr_matrix(X_test['item_condition_id'].values.reshape(-1,1)

- 1.)

Notice that I’ve used -1 because this feature contains 5 types of values between (1–5) so -1 converts them to a range of (0–4). This will give us an advantage while converting to sparse data.

Now as the final step, we’ll be stacking these features column-wise.

I will now convert this preprocessed data into a binary form in which the values will only be either 1s or 0s.

X_tr_binary = (X_tr>0).astype(np.float32)

X_cv_binary = (X_cv>0).astype(np.float32)

X_test_binary = (X_test>0).astype(np.float32)

The advantage of this step is that now we’ll be having 2 datasets with a good variance to work on.

Modeling

It’s time for testing some models on our data. The models that we’ll be trying are-

- Ridge regressor

- Linear SVR

- SGD Regressor

- Random Forest Regressor

- Decision Tree Regressor

- XGBoost Regressor

Ridge Regressor on normal data

We use linear regression to find the optimal hyperplane (the red line in the above gif) such that the loss or square of the sum of distances of each point from the plane/line is minimum. We can notice that the loss will be minimum if we consider the line obtained at iterations=28. Ridge regression is also known as Linear Regression with L2 Regularization which means it uses the sum of the square of weights as a penalty. The penalty term is added to restrict the model from overfitting (capturing noise). The Ridge regression has just 1 hyperparameter **λ **that is multiplied with the penalty/regularization term and it decides the degree of underfitting the model undergoes. The greater the value of λ, the more we under-fit. alpha is simply the regularization strength and it must be a positive float. So as alpha increases, the underfitting also increases.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot(alpha_list, train_loss, label='train loss')

plt.plot(alpha_list, test_loss, label='test loss')

plt.title('alpha VS RMSLE-loss plot')

plt.xlabel('Hyperparameter: alpha')

plt.ylabel('RMSLE loss')

plt.xscale('log')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

-

We can observe that as alpha decreases, the model starts overfitting.

-

The test loss is minimum at alpha=1.

Okay, so our Ridge returned a loss of 0.4232 on cv data.

Ridge Regressor on binary data

Now we’ll be using the Ridge regressor on the binary data

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot(alpha_list, train_loss, label='train loss')

plt.plot(alpha_list, test_loss, label='test loss')

plt.title('alpha VS RMSLE-loss plot (on binary features)')

plt.xlabel('Hyperparameter: alpha')

plt.ylabel('RMSLE loss')

plt.xscale('log')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

- We can observe that the loss is minimum at alpha=100.

Our Ridge regressor returned a loss of 0.4335 on cv data.

Let’s Try SGD-Regressor (as SVR) on Binary data

Let’s quickly refresh what SGD is and how it works. Remember the loss that I mentioned in Ridge regression? Well, there are different types of losses, let’s understand this geometrically. If a regression problem is all about finding the optimal hyperplane that best fits our data, a loss simply means how much our data differs from the hyperplane. So, a low loss means that the points don’t differ much from our hyperplane and the model performs well and vice-versa. In the case of linear regression, the loss is a squared loss and it is obtained by taking the sum of squared distances of data points from the hyperplane divided by the number of terms.

Loss functions are important because they define what the hyperplane will be like. There are other algorithms called the Gradient Descent that make use of these loss-functions and update the parameters of the hyperplane such that it perfectly fits the data. The goal here is to minimize the loss. SGD is one optimized algorithm that updates the parameters of the hyperplane by reducing the loss step by step. It is done by calculating the gradient of the loss function with respect to the features and then using those gradients to descent towards the minima. In the above diagram (left part), we can see how the algorithm is reaching the minima of loss function by taking the right step downhill, and with each step in the correct direction, the parameters are getting updated which leads to a better fitting hyperplane (right part). To know more about the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) algorithm you can check this wonderful blog.

Here are some other common losses but we’ll be using ‘Huber’, ‘epsilon_insensitive’, and ‘squared_epsilon_insensitive’ for the hyperparameter tuning of this model.

The random search cross-validation tells us that ‘squared_epsilon_insensitive’ loss with L2 regularization works best for this data. By the way, ‘squared_epsilon_insensitive’ loss is one of the losses used by another well-known machine learning algorithm Support Vector Machine which uses margin maximization technique by making the use of support vectors to generate a better fitting hyperplane.

- In this diagram, the dotted lines are called decision boundaries, and the points lying on the dotted lines are called support vectors and the objective of SVR is to maximize the distance between these decision boundaries.

But why is margin maximization so important that it makes SVM one of the top ML algorithms? Let’s quickly understand this using a simple classification problem where we need to find an optimal hyperplane that separates the blue and red points.

- Look at the two planes in the figure denoted by the names Hyperplane and Optimal Hyperplane. Well anyone can tell that the Optimal Hyperplane is much better at separating the blue and red points than the other plane and using SVM, this optimal hyperplane is almost guaranteed.

One fun fact is that the flat bottom part in the ‘squared_epsilon_insensitive’ loss is because of this margin maximization trick. You can refer to this and this blog to learn more about SVR.

SGD Regressor (as SVR) returned a loss of 0.4325… on cv data.

Let’s try SGD regressor (as linear regressor) on binary data

Here we’ll be performing all the previous step procedures but on binary data.

The random search cross-validation tells us that ‘squared_loss’ loss with L2 regularization works best for this data. By the way, this setup of squared_loss with L2 regularization sounds familiar right? This is exactly what we used in the Ridge regression model. Here we are approaching this from an optimization problem’s perspective because SGDRegressor gives us much more hyperparameters to play around with and fine-tune our model.

SGD Regressor (as linear regressor) returned a loss of 0.4362 on cv data.

Linear SVR on normal data

Let’s try Support Vector Regressor on normal data. The hyperparameter here is C that is also the reciprocal of alpha which we discussed in Ridge regression.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot(C, train_loss, label='train loss')

plt.plot(C, test_loss, label='test loss')

plt.title('alpha VS RMSLE-loss plot (on binary features)')

plt.xlabel('Hyperparameter: C (1/alpha)')

plt.ylabel('RMSLE loss')

plt.xscale('log')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

- We can see that 0.1 is the best hyperparameter value of hyperparameter C that gives us the minimum test loss.

Linear SVR returned a loss of 0.4326 on the CV of normal data.

Linear SVR on binary data

Now we’ll try Support Vector Regressor on binary data. The hyperparameter here is again C that is also the reciprocal of alpha which we discussed in Ridge regression.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot(C, train_loss, label='train loss')

plt.plot(C, test_loss, label='test loss')

plt.title('alpha VS RMSLE-loss plot (on binary features)')

plt.xlabel('Hyperparameter: C (1/alpha)')

plt.ylabel('RMSLE loss')

plt.xscale('log')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

- We can see that 0.01 is the best hyperparameter value of hyperparameter C that gives us the minimum test loss.

Linear SVR returned a loss of 0.4325 on the cv of binary data.

Tree-based models

The tree-based models below were taking too much time to fit (more than 60 mins) so I reduced the features using Ridge regressor on binary data.

Note: Another dimensionality technique that I tried was truncated-SVD but it required a lot of RAM (more than 16 GB) for computation and since this is a kernel challenge, using the complete data didn’t make much sense.

Selecting top features for tree-based models:

from sklearn.feature_selection import SelectFromModel

from sklearn.linear_model import SGDRegressor

regressor = Ridge(alpha=100)

selection = SelectFromModel(regressor)

selection.fit(X_tr_binary, y_train_std.ravel())

X_train_top = selection.transform(X_tr_binary)

X_cv_top = selection.transform(X_cv_binary)

X_test_top = selection.transform(X_test_binary)

Decision Tree

Our first tree-based model is a Decision Tree, before using this on our dataset, let’s first quickly understand how it works.

Decision Trees are made up of simple if-else statements and using these conditions they decide how to predict the price of a product given its name, conditioning, etc. Geometrically speaking, they fit on the data using several hyperplanes that are parallel to the axes. While training a tree, the tree learns these if-else statements by using and verifying the train data. And when it is trained, it uses these learned if-else conditions to predict the value of test data. But how does it decide how to split the data or what feature to consider while splitting the data and construct a complete tree? Well, it uses something called entropy which is a measure of certainty to construct the tree. Decision trees have several hyperparameters but we’ll be considering only the 2 important ones-

- max_depth: It denotes the maximum depth of a decision tree. So if the max_depth is supposed 4, while training, the tree constructed will not have a depth more than 4.

- min_samples_split: It denotes the minimum number of data points that must be present to perform a split or consider an if-else condition on it. So if the min_samples_split is supposed 32, while training, the tree constructed will not apply an if-else condition if it sees less than 32 data points.

Both the above hyperparameters restrict a decision tree from either underfitting or overfishing. A high max_depth and a low min_samples_split value makes decision trees more prone to overfitting and vice-versa.

-

In this figure, we can see how a trained decision tree algorithm tries to fit on the data, notice how the fitting lines are made up of axes parallel lines.

-

We can also notice how a decision tree with a greater value of max_depth is prone to capture noisy points also.

I will not go into the internal working of decision trees in this blog since it will make it too long, to learn more about the internal working of a decision tree, you can check out this awesome blog.

Let’s perform some hyperparameter tuning on our decision tree using RandomSearchCV and check what are the best hyperparameters for our tree.

The best hyperparameter values returned are max_depth=64 and min_samples_split = 64. Now let’s check the loss obtained after training a decision tree on these hyperparameters.

The loss values are not that great given that it took 14 mins to train. Our Linear models have outperformed the decision tree model by far.

Random forest — (max_depth=3, n_estimators=100)

Now let’s use another awesome tree-based model or I should say models to model our data. Random forests are ensembles that are made up of multiple models. The idea is to use random parts of the data to train multiple models and then use the average predictions from these multiple models as the final value. This makes sense because of training several models using random parts of complete data creates models that are to some extent biased in different ways. Now by taking the average prediction from all these models, in the end, results in a better-predicted value.

The name Random Forest comes from Bootstrap sampling which we use in sampling data randomly from the training dataset and since we use multiple decision trees as our base models, it has the word forest.

The above diagram denotes how Random Forest trains different base learners denoted as Tree 1, Tree 2, … using randomly sampled data and then collects and averages the predictions from these trees.

Random Forest has multiple hyperparameters but for our data, we’ll be using just 2: - n_estimator: this denotes the number of base models that we want our random forest model to have. - max_depth: This denotes the maximum depth of each base model i.e. the decision tree.

Let’s train a random forest model and perform some hyperparameter tuning on it.

The training time for this model was about 23 mins.

We can see that this model does not perform well on the given dataset and the results are not at all good.

Random forest — (max_depth=4, n_estimators=200)

Here I’ve used the same model but with some changes in the architecture. I’ve increased the max_depth to 4 and the number of base learners to 200. Let’s see how the model performs.

The training time for this model was about 65 mins.

The results are slightly better than the previous Random forest model but still not even close to our Linear models.

XGBoost — (max_depth=4, n_estimators=200)

This is the final tree-based model that we’ll be trying and it is called XGBoost. XGBoost is a slightly enhanced version of GBDT which again is an ensemble modeling technique. In Gradient boosting, the purpose is to reduce the variance or reduce the underfitting behavior on a dataset. Let’s see how it works.

In GBDT, we start by training our first base model which is typically a high bias decision tree using the train data, then we take the predicted values from this model and calculate the error which is defined by how much the predictions differ from the actual values. Now we train our second base learner but this time instead of using only the train data, we use also use the error obtained from our first base learner and again we take the predicted values from this model and calculate the error. This goes on till all the base learners are covered and as we train the base learners one by one, we notice that the error value slowly diminishes. You can read more about GBDT here. XGBoost is a slightly modified version of GBDT and it uses techniques like row sampling and column sampling which are techniques from Random Forest to construct the base-learners.

Let’s quickly check out the code for XGBoost, I’ll be using 2 hyperparameters:

- n_estimators: which denotes the number of base-learners which are decision tree models.

- max_depth: which denotes the maximum depth of the base learner decision tree.

The model took about 27 mins to train.

The results are not as bad as random forest but not as good as linear models also.

XGBoost — (max_depth=6, n_estimators=500)

Let’s try XGBoost with max_depth=6 and n_estimators=500.

We can see a decent amount of improvement from the previous model but it took the model 78 mins to train.

Let’s compare the different models and their performance:

In the above table, we can see that the tree-based models are taking too much time to compute, in fact, the data I’m using for tree-based is much smaller, I’m using only the top selected binary features from Ridge regressor. So the new data has only around 236k features instead of the original 700k that other linear models are trained on. We can also observe that the minimum loss on cross-validation data that we were able to obtain is 0.4232… let’s try to reduce this further using ensemble modeling.

The Linear models have outperformed other tree-based models so I’ll be using these to create an Ensemble.

Let’s concatenate the results obtained from the top 6 linear models.

Now let’s quickly test a simple ensemble that takes these features as input and computes the output as a mean of these values.

We can observe that the loss has increased slightly, which means that this method alone is not decent enough to produce good scores.

Now let’s check the correlation between these new features because all of them are from linear models and produce a similar loss. If they are heavily correlated, they will not improve the overall loss much.

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

columns = ['y_pred_ridge_binary_tr', 'y_pred_ridge_normal_tr',

'y_pred_svr_normal_tr','y_pred_svr_binary_tr',

'y_pred_sgd_lr_binary_tr', 'y_pred_sgd_svr_binary_tr']

df = pd.DataFrame(y_pred_tr_ensemble, columns=columns)

Var_Corr = df.corr()

sns.heatmap(Var_Corr, xticklabels=Var_Corr.columns,

yticklabels=Var_Corr.columns, annot=True)

plt.title('Correlation between different features.')

plt.show()

- We can see that the results from the underlying models are heavily correlated so there isn’t much scope of getting a marginally well score from building an ensemble on them.

To tackle this, I increased the dimensionality of this data by adding the top features that were gathered from the Linear model on binary data that we used to train the tree-based models.

It’s time to try different models on these newly generated features to see if we can improve the loss.

Let’s try SGD Regressor using different hyperparameters

The above code block represents the best hyperparameters returned by RandomSearchCV.

The CV loss is not up to the mark since we already have a loss of 0.4232… and we are looking for a loss lower than that.

Let’s try Linear SVR and Ridge regressor on the new features

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ridge_loss = np.array(ridge_loss)

linearsvr_loss = np.array(linearsvr_loss)

plt.plot(alpha, ridge_loss.T[0], label='Ridge train')

plt.plot(alpha, ridge_loss.T[1], label='Ridge test')

plt.plot(alpha, linearsvr_loss.T[0], label='linearsvr train')

plt.plot(alpha, linearsvr_loss.T[1], label='linearsvr test')

plt.xlabel('Hyperparameter: alpha or (1/C)')

plt.ylabel('loss')

plt.xscale('log')

plt.title('Linear SVR and Ridge losses')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

- We can see that at alpha=100000, the cv loss returned by Ridge regressor and Linear SVR are minimum. Let’s fit the models on that.

Training a Ridge regressor with alpha = 100000

Training a Linear SVR with C = 0.00001

Okay, by looking at the above table we can tell that the Ridge and LinearSVR models yield the best results, so we’ll be using these to generate one more and the final layer of our ensemble.

Let’s quickly fit the data using these models and concatenate the output that we’ll feed as input to our final ensemble layer.

We’ll now create the final layer of our ensemble using the generated output from the previous layer models. We’ll be using some linear models but before that, let’s test the simple mean results.

The results are better than the LinearSVR model alone but the Ridge still outperforms every model till now.

Let’s try some linear models now for the final layer:

SGD Regressor

Let’s try Ridge and Linear-SVR as the final layer model

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ridge_loss = np.array(ridge_loss)

linearsvr_loss = np.array(linearsvr_loss)

plt.plot(alpha, ridge_loss.T[0], label='Ridge train')

plt.plot(alpha, ridge_loss.T[1], label='Ridge test')

plt.plot(alpha, linearsvr_loss.T[0], label='linearsvr train')

plt.plot(alpha, linearsvr_loss.T[1], label='linearsvr test')

plt.xlabel('Hyperparameter: alpha or (1/C)')

plt.ylabel('loss')

plt.xscale('log')

plt.title('Linear SVR and Ridge losses')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

- The results are close but the Ridge regressor outperforms LinearSVR.

Here are all the models that have been used for the ensemble, compared in a tabular form.

Finally, let’s predict the prices of the test dataset and check how our ensemble performs on the Kaggle leaderboard.