The GNU make program was created in 1976 to help build executable programs from source code files.

While it was originally developed to assist with programming in the c language, it is not limited to that language or even to the task of compiling code.

According to the manual, one "can use it to describe any task where some files must be updated automatically from others whenever the others change."

The make program has gone far beyond it’s role as a build tool to become a workflow system.

When you run the make command, it looks for a file called Makefile (or makefile) in the current working directory.

This file contains recipes that describe discrete actions that combine to create some output.

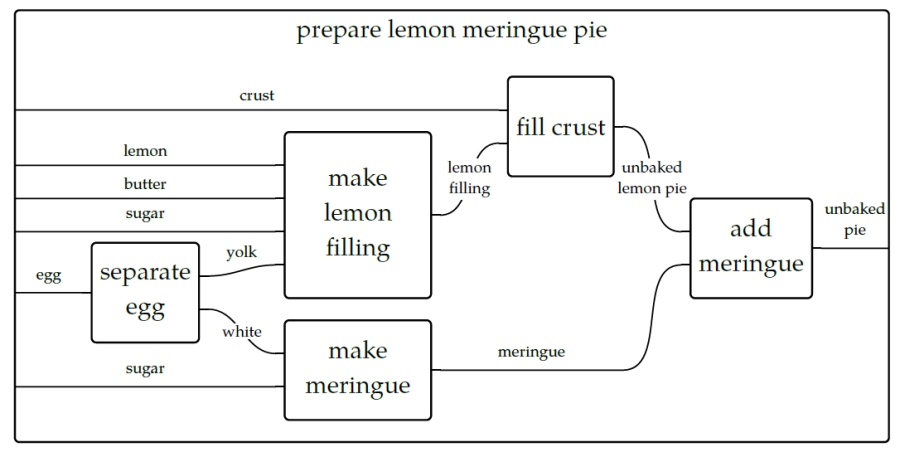

Think of how a recipe for a lemon pie has steps that need to be completed in a particular order and combination.

For instance, we need to separately create the crust, filling, and meringue and then put them together and bake them before we can enjoy our tasty treat.

We can visualize this with something called a "string diagram" like below.

It’s not really important if you make the pie crust the day before and keep it chilled, and the same might hold true for the filling, but it’s certainly true that the crust needs to go into the dish followed by the filling and finally the meringue. An actual recipe might refer to a generic recipes for the crust and meringue in parts of the book and list the steps just for the lemon filling and baking instructions.

We can write a Makefile to mock up these ideas.

We’ll use shell scripts to pretend we’re assembling the various ingredients into some output like crust.txt and filling.txt.

For instance, I’ve written a combine.sh script that expects a file name and a list of "ingredients" to put into the file:

$ ./combine.sh usage: combine.sh FILE ingredients

I can pretend to make the "crust" like this:

$ ./combine.sh crust.txt flour butter water

There is now a crust.txt file with the following contents:

$ cat crust.txt Will combine flour butter water

It’s common for a recipe in a Makefile to create an output file such as this, but it’s not necessary.

Note in this example from the pie directory that the clean target actually removes files rather than making them:

all: crust.txt filling.txt meringue.txt (1) ./combine.sh pie.txt crust.txt filling.txt meringue.txt (2) ./cook.sh pie.txt 375 45 filling.txt: (3) ./combine.sh filling.txt lemon butter sugar meringue.txt: (4) ./combine.sh meringue.txt eggwhites sugar crust.txt: (5) ./combine.sh crust.txt flour butter water clean: (6) rm -f crust.txt meringue.txt filling.txt

-

This defines a target called

all. The first target will be the one run when no target is specified. Convention holds that thealltarget will run all the targets necessary to accomplish some default goal like building a piece of software. Here we want to create thepie.txtfile from the component files and "cook" it. The nameallis not as important as it being defined first. The target name is followed by a colon and then any dependencies that must be satisfied before running this target. -

The

alltarget has two commands to run. Each command is indented with aTabcharacter. -

This is the

filling.txttarget. The goal of this target is to create the file called "filling.txt". It’s common but not necessary to use the output file name as the target name. This target has just one command which is to combine the ingredients for the filling. -

This is the

meringue.txttarget, and it combines the egg whites and sugar. -

This is the

crust.txttarget that combines flour, butter, and water. -

It’s common to have a

cleantarget to remove any files that were created in the normal course of building.

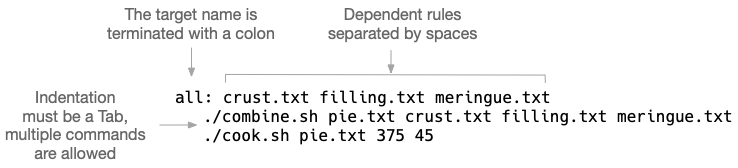

As you can see above, the target (also sometimes called a "rule") has a name followed by a colon.

Any dependent actions can be listed after the colon in the order you wish them to be run.

The actions for a target must be indented with a Tab character, and you are allowed to define as many commands as you like.

Each recipe in a Makefile is called a "target," "rule," or "recipe."

The order of the targets is not important beyond the first target being the default.

Targets can reference other targets defined earlier or later in the file.

To run a specific target, we can run make <target> to have make run the commands for a given recipe:

$ make filling.txt ./combine.sh filling.txt lemon butter sugar

And now there is a file called filling.txt:

$ cat filling.txt Will combine lemon butter sugar

If we try to run this target again, we’ll be told there’s nothing to do because the file already exists:

$ make filling.txt make: `filling.txt' is up to date.

One of the reasons for the existence of make is precisely not to do extra work to create files unless some underlying source has changed.

In the course of building software or running a pipeline, it may not be necessary to generate some output unless the inputs have changed (such as the source code being modified).

To force make to run the filling.txt target, we can either remove that file or run make clean to remove any of the files that have been created:

$ make clean rm -f crust.txt meringue.txt filling.txt pie.txt

If you run the make command with no arguments, and it will automatically run the first target.

This is the main reason to place the all target (or something like it) first.

Be careful not to put something destructive like a clean target first as you might end up accidentally running it and removing valuable data!

Let’s run make with the above Makefile and see the output:

$ make (1) ./combine.sh crust.txt flour butter water (2) ./combine.sh filling.txt lemon butter sugar (3) ./combine.sh meringue.txt eggwhites sugar (4) ./combine.sh pie.txt crust.txt filling.txt meringue.txt (5) ./cook.sh pie.txt 375 45 (6) Will cook "pie.txt" at 375 degrees for 45 minutes.

-

We run

makewith no arguments. It looks for the first target in a file calledMakefilein the current working directory. -

The

crust.txtrecipe is being run first. Because we didn’t specify a target,makeruns thealltarget which is defined first, and this target lists thecrust.txtas it’s first dependency. -

Next the

filling.txttarget is run. -

Followed by the

meringue.txt. -

Next we assemble

pie.txt. -

And then we "cook" the pie at 375 degrees for 45 minutes.

If you run make again, you’ll see the intermediate steps to produce the crust.txt, filling.txt, and meringue.txt files are skipped because those files already exist:

$ make ./combine.sh pie.txt crust.txt filling.txt meringue.txt ./cook.sh pie.txt 375 45 Will cook "pie.txt" at 375 degrees for 45 minutes.

If you want to force them to be recreated, you can run make clean && make:

$ make clean && make rm -f crust.txt meringue.txt filling.txt pie.txt ./combine.sh crust.txt flour butter water ./combine.sh filling.txt lemon butter sugar ./combine.sh meringue.txt eggwhites sugar ./combine.sh pie.txt crust.txt filling.txt meringue.txt ./cook.sh pie.txt 375 45 Will cook "pie.txt" at 375 degrees for 45 minutes.

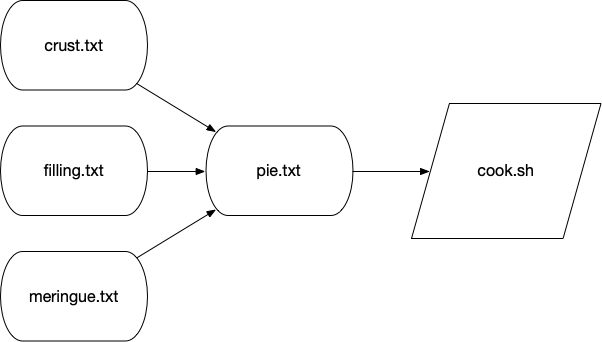

Each target can specify other targets as prerequisites or dependencies that must be accomplished first. These actions create a graph structure where there is some starting point and paths through targets to finally create some output file(s). The path described for any target should be a directed (from a start to a stop) acyclic (having no cycles or infinite loops) graph or a DAG:

Many analysis pipelines are just that — a graph of some input like a FASTA sequence file and some transformations (trimming, filtering, comparisons) into some output (e.g., BLAST hits, gene predictions, functional annotations).

You would be surprised at just how far make can be abused to document your work and even create fully functional analysis pipelines!

I believe it helps to use make for its intended purpose at least once in your life in order to really understand why it exists.

Let’s take a moment to write and compile a "Hello, World" example in the c language.

In the c-hello directory, you will find a simple c program that will print "Hello, World!".

Here is the hello.c source code:

#include <stdio.h> (1)

int main() { (2)

printf("Hello, World!\n"); (3)

return 0; (4)

} (5)

Let’s take a moment to learn just enough c to be dangerous going line-by-line:

-

Like

bash, the#character introduces comments in theclanguage, but this is a special comment that allows external modules of code to be used. Here, we want to use theprintf(print-format that we saw in the previous chapter), so we need toincludethe standard I/O (input/output) module calledstdio. We actually only need to include the "header" file,stdio.h, to get at the function definitions in that module. This is a standard module, and theccompiler will look in various locations for any included files to find it. There may come times when you are unable to compilec(orc++programs) from source code because some header file cannot be found. For example, thegziplibrary is often used to de/compress data, but it is not always installed in a libary form that other programs mayincludein this way. Therefore you will have to download and install thelibgzprogram, being sure to install the headers into the properincludedirectories. Note that package managers likeapt-getandyumoften have-devor-develpackages that you have to install to get these headers, e.g., you would install bothlibgzandlibgz-devor whatnot. -

This is the start of a function declaration in

c. Theint(an "integer") is the return value of the function calledmain(). The parentheses()list the parameters to the function. There are none, so the the parens are empty. The opening curly brace{shows the start of the code that belongs to the function. Note thatcwill automatically execute themain()function, and everycprogram must have amain()function where the program starts. -

The

printf()function will print the given string to the command line. This function is defined in thestdiolibrary, which is why we need to#includethe header file above. -

returnwill exit the function and return the value0. Since this is the return value for themain()function, this will be the exit value for the entire program. The value0indicates that the program ran normally — think "zero errors." Any non-zero value would indicate a failure. -

This curly brace

}is the closing mate for the one on line 2 and marks the end of themain()function.

To turn that into an executable program you will need to have a c compiler on your machine.

We can use the gcc (GNU c compiler) with this command:

$ gcc hello.o

That will create a file called a.out which is an executable file.

On my Mac, this is what file will report:

$ file a.out a.out: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

And I can execute that:

$ ./a.out Hello, World!

I don’t like the name a.out, though, so I can use the -o option to name the output file called hello:

$ gcc -o hello hello.c

Run the resulting hello executable.

You should see the same output.

Rather than typing gcc -o hello hello.c every time I modify the hello.c, I can put that as a "target" into a Makefile:

hello: gcc -o hello hello.c

And now I can type make hello or just make if this is the first target:

$ make gcc -o hello hello.c

If I run make again, nothing happens because the hello.c file hasn’t changed:

$ make make: `hello' is up to date.

Alter your hello.c file to print "Hola" instead of "Hello," and then try running make again:

$ make make: `hello' is up to date.

We can force make to run the targets using the -B option:

$ make -B gcc -o hello hello.c

And now our new program has been compiled:

$ ./hello Hola, World!

This is clearly a trivial example, and you may be wondering how this is actually a time saver.

A real-world project in c or any language would likely have multiple .c files with headers (.h files) describing their functions so that they could be used by other .c files.

The c compiler would need to turn each .c file into .o ("out") files and then link them together into a single executable.

Imagine you have dozens of .c files, and you change one line of code in one file.

Do you want to type dozens of commands to recompile and link all your code?

Of course not!

You would build a tool to automate those actions for you.

We can add targets to the Makefile that don’t generate new files.

It’s common to have a clean target that will clean up files and directories that we no longer need.

Here I can create clean target to remove the hello executable.

clean: rm -f hello

If I want to be sure that the exeuctable is removed before every running the hello target, I can add it as a dependency:

hello: clean gcc -o hello hello.c

It’s good form to document for make that this is a "phony" target because the result of the target is not a new file to "make."

We use the .PHONY: target and list all the phonies.

Here is our complete Makefile now:

$ cat Makefile .PHONY: clean hello: clean gcc -o hello hello.c clean: rm -f hello

If you make in the c-hello directory with this Makefile, you should see this:

$ make rm -f hello gcc -o hello hello.c

And there should now be a hello executable in your directory that you can run:

$ ./hello Hello, World!

Notice that the clean target can be listed as a dependency to the hello target even before the target itself is mentioned.

make will read the entire file and then use the dependencies to resolve the graph.

If you were to put "foo" as an additional dependency to hello and then try to running make again, you would see this:

$ make make: *** No rule to make target `foo', needed by `hello'. Stop.

When we write bash programs, the program is executed from the top to the bottom, each statement one after the other.

The Makefile allows us to write independent groups of actions that are ordered by their dependencies.

They are essentially like functions in a higher-level language.

We have essentially written a program who’s output is … a program.

I’d encourage you to cat hello to see what the hello program "looks" like.

It’s mostly binary information that will look like jibberish, but you will probably be able to make out some plain English, too.

You can also use strings hello to extract just the "strings" of text.

Let’s look at how we can abuse Makefiles to create shortcuts for commands.

Here we will say "Hello, World!" on the command line using the echo command:

.PHONY: hello (1) hello: (2) echo "Hello, World!" (3)

-

Since the

hellotarget doesn’t actually produce a file, we list it as a "phony" target. -

This is the

hellotarget. The name of the target should be composed only of letters and numbers, should have no spaces before it, and is followed by a colon (:). -

The command(s) to run for the

hellotarget are listed on lines that are indented with a tab character.

I often use a Makefile only to remember how to invoke a command with various arguments.

That is, I might write an analysis pipeline and then document how to run the program on various data sets with all their parameters.

In this way I’m documenting my work in a way that I can immediately reproduce it simply by running the target!

Here is an example of a Makefile I wrote to document how I ran the Centrifuge app for making taxonomic assignments to short reads:

INDEX_DIR = /data/centrifuge-indexes (1)

clean_paired:

rm -rf $(HOME)/work/data/centrifuge/paired-out

paired: clean_paired (2)

./run_centrifuge.py \ (3)

-q $(HOME)/work/data/centrifuge/paired \ (4)

-I $(INDEX_DIR) \ (5)

-i 'p_compressed+h+v' \

-x "9606, 32630" \

-o $(HOME)/work/data/centrifuge/paired-out \

-T "C/Fe Cycling"

-

Here I define the variable

INDEX_DIRand assign a value. Note that there must be spaces on either side of the=. I prefer ALL_CAPS for my variable names, but this just personal preference. -

Run the

clean_pairedtarget prior to running this target. This ensures that there is no leftover output from a previous run. -

This action is long, so I used backslashes

\as on the command line to indicate the command continues to the next line. -

To have

makeuse the value of the variable, you deference like$(VAR). Here we can use the environmental variable$HOMEas the$(HOME). -

The

$(INDEX_DIR)refers to the variable defined at the top.

Following is an example of how to write a workflow as make targets.

The goal is to download the yeast genome and characterize various gene types as "Dubious," "Uncharacterized," "Verified," and such.

This is accomplished with a collection of command-line tools such as wget, grep, and awk combined with a custom shell script called download.sh all pieced together and run in order by make:

.PHONY: all fasta features test clean

FEATURES = http://downloads.yeastgenome.org/curation/chromosomal_feature/SGD_features.tab

all: fasta genome chr-count chr-size features gene-count verified-genes uncharacterized-genes gene-types terminated-genes test

clean:

find . \( -name \*gene\* -o -name chr-\* \) -exec rm {} \;

rm -rf fasta SGD_features.tab

fasta:

./download.sh

genome: fasta

(cd fasta && cat *.fsa > genome.fa)

chr-count: genome

grep -e '^>' "fasta/genome.fa" | grep 'chromosome' | wc -l > chr-count

chr-size: genome

grep -ve '^>' "fasta/genome.fa" | wc -c > chr-size

features:

wget -nc $(FEATURES)

gene-count: features

cut -f 2 SGD_features.tab | grep ORF | wc -l > gene-count

verified-genes: features

awk -F"\t" '$$3 == "Verified" {print}' SGD_features.tab | \

wc -l > verified-genes

uncharacterized-genes: features

awk -F"\t" '$$2 == "ORF" && $$3 == "Uncharacterized" {print $$2}' \

SGD_features.tab | wc -l > uncharacterized-genes

gene-types: features

awk -F"\t" '{print $$3}' SGD_features.tab | sort | uniq -c > gene-types

terminated-genes:

grep -o '/G=[^ ]*' palinsreg.txt | cut -d = -f 2 | \

sort -u > terminated-genes

test:

pytest -xv ./test.py

I won’t bother commenting on all the commands.

Mostly I want to demonstrate how far we can abuse a Makefile to create a workflow.

Not only have we documented all the steps, but they are runnable with nothing more than the command make!

Absent using make, we’d have to write a shell script to accomplish this or, more likely, move to a more powerful language like Python.

The resulting program written in either language would probably be longer, buggier, and more difficult to understand.

Sometimes, all you really need is a Makefile and some shell commands.

As you bump up against the limitations of make, you may choose to move to a workflow manager.

There are literally hundreds to choose from including:

-

Snakemake which extends the basic concept

makewith Python. -

The Common Workflow Language (CWL) defines workflows and parameters in a configuration file (in YAML), and you use tools like

cwltoolorcwl-runner(both implemented in Python) to execute the workflow with another configuration file that describes the arguments. -

The Workflow Description Language (WDL) takes a similar approach to describing workflows and arguments and can be run with the Cromwell engine.

-

Pegasus allows you to use Python code to describe a workflow that then is written to an XML file that is the input for the engine that will run your code.

-

Nextflow is similar in that you use a full programming language called "Groovy" (a subset of Java) to write a workflow that can be run by their engine.

All of these systems have the same basic ideas as make, so understanding how make works and how to write the pieces of your workflow and how they interact is the basis for any larger analysis workflow you may create.

Here are some other resources you can use to learn about Make:

-

Online manual: https://www.gnu.org/software/make/manual/make.html

-

GNU Make Book by John Graham-Cumming, No Starch Press, 2015: https://nostarch.com/gnumake

-

Managing Projects with GNU Make by Robert Mecklenburg, O’Reilly, 2009: http://shop.oreilly.com/product/9780596006105.do