This Internet of Chuffs client is designed to stream audio from an I2S microphone (e.g. the ICS43432 MEMS microphone) connected to a Raspberry Pi over a cellular interface to an ioc-server. The instructions below cover the entire installation of the Raspberry Pi side of the system, including testing that the whole system works.

First, load Raspbian into your Raspberry Pi. I used the minimal image, no desktop, and once I'd created the SD card I also created an empty file on the boot partition called SSH (all in caps, no extension); this switches on SSH so, provided you can determine what IP address the Pi has been allocated, you can do everything else from an SSH terminal (default user name pi and default password raspberry).

If you are using a Pi Zero W with no Ethernet connector and so need to get at it over Wifi, create a file called wpa_supplicant.conf in the boot partition of the SD card and in that file put:

country=GB

ctrl_interface=DIR=/var/run/wpa_supplicant GROUP=netdev

update_config=1

network={

ssid="SSID"

psk="password"

key_mgmt=WPA-PSK

}

...where SSID is replaced by the SSID of your Wifi network and password is replaced by the password for your Wifi network.

If, at some later point, you want to disable BT and Wifi (so that the system uses cellular as you will intend), add the following to /boot/config.txt:

# Disable BT and Wifi

dtoverlay=pi3-disable-bt

dtoverlay=pi3-disable-wifi

...and also enter:

sudo systemctl disable hciuart

Next, set up an admin user as follows:

sudo adduser username

...where username is replaced by the user you wish to add. Add this to all the groups that are around with:

sudo usermod username -a -G adm,dialout,cdrom,sudo,audio,video,plugdev,games,users,input,netdev,spi,i2c,gpio

...where username is replaced by the user you added above.

Add this user to the sudo group by creating a file /etc/sudoers.d/sudoers and putting in it the single line username ALL=(ALL) ALL (where username is replaced by the user you added above).

Set the permissions on that file to 0440 with:

sudo chmod 0440 /etc/sudoers.d/sudoers

Logout, log in again as the new user and verify that you can become root with:

su -i

Assuming you can, remove the pi user with:

sudo deluser pi

Configuration of the I2S interface on the Raspberry Pi is based on the instructions that can be found here:

http://www.raspberrypi.org/forums/viewtopic.php?f=44&t=91237

Edit /boot/config.txt to make sure that the following two lines are not commented-out:

# Add audio and I2S audio at that

dtparam=audio=on

dtparam=i2s=on

Next we need to build and load the ICS43432 microphone driver. This is already available as part of the Linux source tree but is not built or loaded by default.

These steps are based on this blog post:

https://www.raspberrypi.org/forums/viewtopic.php?t=173640

Install a few required utilities:

sudo apt-get install bc

sudo apt-get install libncurses5-dev

Download the correct source version for your kernel/ARM architecture and clean it up using the rpi-source utility as follows:

sudo wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/notro/rpi-source/master/rpi-source -O /usr/bin/rpi-source

sudo chmod +x /usr/bin/rpi-source

/usr/bin/rpi-source -q --tag-update

rpi-source

If you receive an error like this:

gcc version check: mismatch between gcc (6) and /proc/version (4.9.3)

...where the GCC version is higher than the /proc/version version, then that's OK, just run rpi-source again with the parameter --skip-gcc. rpi-source may ask you to install other things along the way; do what it says. When it has completed you should have the following file (with many others):

~/linux-xxxx.../sound/soc/codecs/ics43432.c

...where xxxx... is a long hex string specific to your kernel version.

CD to the ~/linux-xxxx... directory. Make a backup of your current .config file with:

cp .config back.config

Now run:

make menuconfig

Use the arrow keys to navigate down the menu tree as follows:

Device drivers ---> Sound card support ---> Advance Linux Sound Architecture ---> ALSA for SoC audio support ---> CODEC drivers ---> InvenSense ICS43432 I2S microphone codec

...and press the space bar to put an m against that entry. Exit by pressing ESC lots of times, saving the file as .config when prompted.

Now include this change and build the codecs module with:

sudo make prepare

sudo make M=sound/soc/codecs

Look in the sound/soc/codecs directory again and you should now see the file snd-soc-ics43432.ko.

Try adding the module manually with:

sudo insmod sound/soc/codecs/snd-soc-ics43432.ko

If this fails with the error Could not insert module, invalid module format then you've got the wrong version of Linux kernel source for the Linux binary you are using and you need to repeat this section. The version of the Linux kernel that you downloaded can be found by looking at the top of the Makefile in the top level directory of your unpacked download tree, where you will find something like:

VERSION = 4

PATCHLEVEL = 9

SUBLEVEL = 59

EXTRAVERSION =

NAME = Roaring Lionus

Note that this does NOT include the ARM architecture version, which is set up by the rpi-source utility itself. The Linux version you are running can be found with uname -r.

To find the Linux kernel version your module thinks it was compiled with, use:

sudo modinfo sound/soc/codecs/snd-soc-ics43432.ko

It is worth noting that different Raspberry Pi boards can have processors with different ARM architectures and hence hand-built modules are not necessarily fully compatible (e.g. this was true of my Raspberry Pi B+ (v7 ARM architecture) and my Pi Zero W (v6 ARM architecture)); the module version will be that of the ARM architecture of the processor it was built on. To check your CPU version use:

cat /proc/cpuinfo

NOTE: when you do sudo apt-get upgrade this might happen again if the Linux version changes as a result. You can check the Linux version using uname -r; if the version has changed you need to re-download the Linux source with rpi-source and repeat the actions of this section to build a compatible snd-soc-ics43432.ko file.

Install the module with:

sudo cp sound/soc/codecs/snd-soc-ics43432.ko /lib/modules/`uname -r`/

Run sudo depmod so as to let Linux work out the dependencies.

Finally, to load the module at boot, edit the file /etc/modules to add the line:

snd-soc-ics43432

Reboot and use lsmod to check that the driver has been automatically loaded. The output should look something like this:

Module Size Used by

cfg80211 544545 0

rfkill 20851 2 cfg80211

snd_bcm2835 24427 0

snd_soc_bcm2835_i2s 7480 0

bcm2835_gpiomem 3940 0

uio_pdrv_genirq 3923 0

uio 10204 1 uio_pdrv_genirq

fixed 3285 0

snd_soc_ics43432 2287 0

snd_soc_core 180471 2 snd_soc_ics43432,snd_soc_bcm2835_i2s

snd_compress 10384 1 snd_soc_core

snd_pcm_dmaengine 5894 1 snd_soc_core

snd_pcm 98501 4 snd_pcm_dmaengine,snd_soc_bcm2835_i2s,snd_bcm2835,snd_soc_core

snd_timer 23968 1 snd_pcm

snd 70032 5 snd_compress,snd_timer,snd_bcm2835,snd_soc_core,snd_pcm

ip_tables 13161 0

x_tables 20578 1 ip_tables

ipv6 408900 24

If snd_soc_ics43432 does not appear in the list, check what went wrong during boot using journalctl -b and/or dmesg.

Now we need to create a device tree entry to make use of this driver. Create a file i2s-soundcard-overlay.dts with this content:

/dts-v1/;

/plugin/;

/ {

compatible = "brcm,bcm2708";

fragment@0 {

target = <&i2s>;

__overlay__ {

status = "okay";

};

};

fragment@1 {

target-path = "/";

__overlay__ {

card_codec: card-codec {

#sound-dai-cells = <0>;

compatible = "invensense,ics43432";

status = "okay";

};

};

};

fragment@2 {

target = <&sound>;

master_overlay: __dormant__ {

compatible = "simple-audio-card";

simple-audio-card,format = "i2s";

simple-audio-card,name = "soundcard";

simple-audio-card,bitclock-master = <&dailink0_master>;

simple-audio-card,frame-master = <&dailink0_master>;

status = "okay";

simple-audio-card,cpu {

sound-dai = <&i2s>;

};

dailink0_master: simple-audio-card,codec {

sound-dai = <&card_codec>;

};

};

};

fragment@3 {

target = <&sound>;

slave_overlay: __overlay__ {

compatible = "simple-audio-card";

simple-audio-card,format = "i2s";

simple-audio-card,name = "soundcard";

status = "okay";

simple-audio-card,cpu {

sound-dai = <&i2s>;

};

dailink0_slave: simple-audio-card,codec {

sound-dai = <&card_codec>;

};

};

};

__overrides__ {

alsaname = <&master_overlay>,"simple-audio-card,name",

<&slave_overlay>,"simple-audio-card,name";

compatible = <&card_codec>,"compatible";

master = <0>,"=2!3";

};

};

Compile and install this as follows:

dtc -@ -I dts -O dtb -o i2s-soundcard.dtbo i2s-soundcard-overlay.dts

sudo cp i2s-soundcard.dtbo /boot/overlays

[Note: ignore the warnings that the dtc compilation process throws up].

Finally, edit the file /boot/config.txt to append the lines:

# Add the MEMS microphone

dtoverlay=i2s-soundcard,alsaname=mems-mic

Now reboot and then check for sound cards with:

arecord -l

...and you should see:

**** List of CAPTURE Hardware Devices ****

card 1: memsmic [mems-mic], device 0: bcm2835-i2s-ics43432-hifi ics43432-hifi-0 []

Subdevices: 1/1

Subdevice #0: subdevice #0

The output from lsmod should now look something like this:

Module Size Used by

cfg80211 544545 0

rfkill 20851 2 cfg80211

snd_soc_simple_card 6297 0

snd_soc_simple_card_utils 5196 1 snd_soc_simple_card

snd_bcm2835 24427 0

bcm2835_gpiomem 3940 0

snd_soc_bcm2835_i2s 7480 2

uio_pdrv_genirq 3923 0

fixed 3285 0

uio 10204 1 uio_pdrv_genirq

snd_soc_ics43432 2287 1

snd_soc_core 180471 4 snd_soc_ics43432,snd_soc_simple_card_utils,snd_soc_bcm2835_i2s,snd_soc_simple_card

snd_compress 10384 1 snd_soc_core

snd_pcm_dmaengine 5894 1 snd_soc_core

snd_pcm 98501 4 snd_pcm_dmaengine,snd_soc_bcm2835_i2s,snd_bcm2835,snd_soc_core

snd_timer 23968 1 snd_pcm

snd 70032 5 snd_compress,snd_timer,snd_bcm2835,snd_soc_core,snd_pcm

ip_tables 13161 0

x_tables 20578 1 ip_tables

ipv6 408900 24

The pins you need on the Raspberry Pi header are as follows:

- Pin 12: I2S clock

- Pin 35: I2S frame

- Pin 38: I2S data in

- Pin 39: ground

- Pin 1: 3.3V

- [Pin 40: I2S data out]

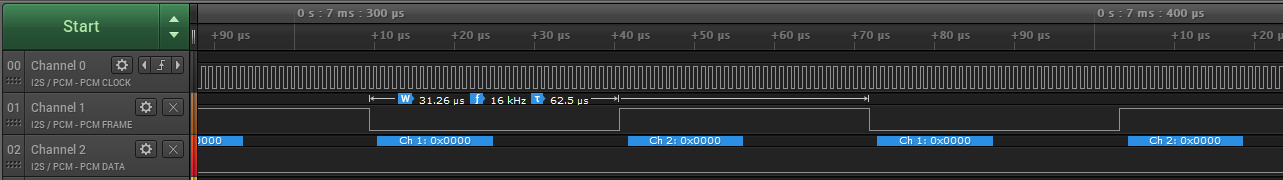

If you want to confirm that all is good, attach an oscilloscope or logic analyser to the pins and activate the pins by requesting a 10 second long recording with:

arecord -Dhw:1 -c2 -r16000 -fS32_LE -twav -d10 -Vstereo test.wav

You should see something like this:

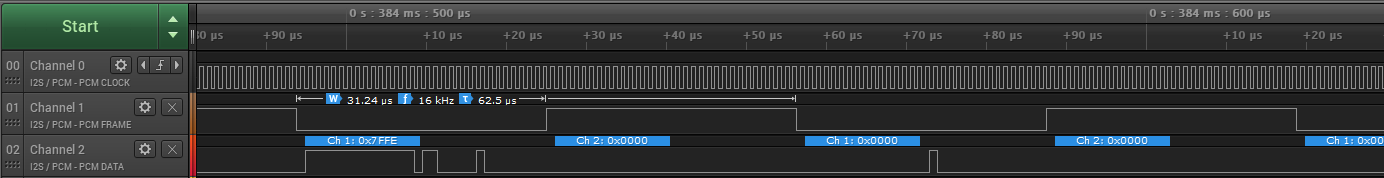

Connect up your ICS43432 MEMS microphone, with the LR select pin grounded, and you should see data flowing something like this:

If you touch the microphone while the recording is running you should see the VU meter displayed in the SSH window change.

To make a proper capture you will need to configure for a mono microphone and a sensible recording level. Create a file called /etc/asound.conf with the following contents:

pcm.mic_hw {

type hw

card memsmic

channels 2

format S32_LE

}

pcm.mic_sv {

type softvol

slave.pcm mic_hw

control {

name "Boost Capture Volume"

card memsmic

}

min_dB -3.0

max_dB 50.0

}

pcm.mic_mono {

type multi

slaves.a.pcm mic_sv

slaves.a.channels 2

bindings.0.slave a

bindings.0.channel 0

}

Check that your configuration is correct by making a recording with this newly defined device:

arecord -Dmic_sv -c2 -r16000 -fS32_LE -twav -d10 -Vstereo test.wav

Now run alsamixer, call up the sound card menu by pressing F6, select mems-mic and then press the TAB key and set the Boost capture volume level (you can try using F4 instead but that is often grabbed by the terminal program and hence may do other things). Use the arrow keys to set a Boost of around 30 dB and press ESC to exit.

Now run another recording and, hopefully, you will get a better sound level in your test.wav file.

For the sections that follow, the device you want to stream audio from is mic_hw; the others we have used above are simply to allow verification of correct configuration with arecord.

This code is linked against the ALSA libraries so you'll need the ALSA development package. Get this with:

sudo apt-get install libasound2-dev

Install git with:

sudo apt-get install git

Install the systemd development world (required to implement a systemd watchdog) with:

sudo apt-get install libsystemd-dev

Install wiringPi with:

git clone git://git.drogon.net/wiringPi

cd wiringPi

./build

Clone this repo with:

git clone https://github.com/RobMeades/ioc-client

Change to the ioc-client directory and run:

sudo make

You should end up with the binary ~/ioc-client/Debug/ioc-client.

If you have the server-side of the IoC set up somewhere and, preferably, also have the log server application running on the same remote machine, you should now be able to connect ioc-client to them with:

~/ioc-client/Debug/ioc-client mic_hw ioc_server:port -g 8 -p 0 -ls log_server:port -ld log_directory_path

...where mic_hw is the device representing the I2S microphone, ioc_server:port is the URL where the ioc-server application is running, 8 represents a good maximum gain (can get a bit noisy when it is quiet otherwise), 0 represents GPIO0, log_server:port is the URL where the ioc logging server is running and log_directory_path is a path where log files can be stored temporarily. Here the connection to the server applications will be direct rather than over a secure connection. When a connection is active GPIO0 will toggle on every transmit; it's probably useful to connect an LED (via a 1k resistor) between that pin and ground.

This section describes how to set up SSH connectivity which will be used below when Making Incoming TCP Connections Over Cellular and Running Everything Automatically.

Generate a key pair:

ssh-keygen -f ~/ioc-client-key -t ecdsa -b 521

Don't add a passphrase as we will need the Raspberry Pi to be able to use the key without manual passphrase entry. Make sure the Raspberry Pi is on-line and copy the public key to the server with:

ssh-copy-id -i ~/ioc-client-key user@host

...replacing user with your username on the server and host with the IP address of the server.

Make sure that you can log in to the server from the Raspberry Pi using SSH and this key with:

ssh -i ~/ioc-client-key user@host -p xxxx

...again replacing user and host with the user name and IP address for the server, and adding -p xxxx with the remote port number if it is not port 22. If you have problems, try adding the -vvv switch to ssh to find out what it's up to while running journalctl -f on the server to determine what it is seeing.

If you find that an SSH tunnel won't connect or there are other end-to-end connectivity issues, try falling back to basic TCP testing with netcat. On the server side run:

netcat -v -l xxxx

...where xxxx is the port number to listen on. If the SSH server is active on port 22 then stop it first, or maybe just try a different port number to start with. On the client side run:

netcat -v host xxxx

...where host is replaced by the address of the server and xxxx is the port. If a connection is made, both ends will say so. Try all of this initially with the Ethernet connection of the Raspberry Pi plugged in but bare in mind that if your server is on the same network then you aren't really testing things. Maybe try running the client-side netcat line on another Linux server on the internet, just to be sure that the server is visible.

If this works from the command line, make sure it also works in the systemd unit files by replacing the line that invokes the SSH client with the netcat client-side line.

First, edit /boot/config.txt to append the lines:

# Allow more power to be drawn from the USB ports, needed for cellular modem

max_usb_current=1

You'll find you need this in poor coverage conditions as cellular can draw more power than the Pi usually provides. Then reboot.

Install minicom with:

sudo apt-get install minicom

Plug in your USB modem into one of the Raspberry Pi's USB ports. I used a Hologram USB stick with a u-blox USB modem, which is a pure modem and requires no usb-modeswitch messing about. I also created a persistent device name for the USB stick using udev. With the USB stick plugged in, enter:

lsusb

Find the entry for your device. Mine was:

Bus 001 Device 006: ID 1546:1102 U-Blox AG

Create a file 90-ioc.rules in /etc/udev/rules.d with the following contents:

#Add modem device

ACTION=="add", KERNEL=="tty*", ATTRS{idVendor}=="1546", ATTRS{idProduct}=="1102", SYMLINK+="modem"

...adjusting the numbers as necessary for your modem and making sure there is a newline at the end. Reboot and check that /dev now includes the device modem. If it doesn't, you can check if there are any errors reading the new rule with:

udevadm test /dev/bus/001/006

...replacing the values 001 and 006 as appropriate for your device.

Note: for reasons I don't understand, minicom and wvdial didn't play well with my /dev/modem device: they seemed to lock it (with a lock file in /var/lock/), then be unable to use it but leave it locked. So you will see below that I continued to use /dev/ttyACM0 with those applications. The rules file, though, is still required, see later on.

Run minicom with:

minicom -b115200 -D/dev/ttyACM0

...and check that typing AT gets the response OK, just to confirm that the Raspberry Pi can talk to the modem. Exit minicom with CTRL-A, X.

Now install PPP and a dialler with:

sudo apt-get install ppp wvdial

Edit the file /etc/wvdial.conf for your modem. For my u-blox modem (on a Hologram USB stick with a Hologram SIM and hence a hologram APN) I used:

[Dialer Defaults]

Init1 = ATZ

Init2 = ATE0 +CMEE=2

Init3 = AT&C1 &D2

Init4 = AT+CGDCONT=1, "IP", "hologram"

Init5 = AT+IPR=460800

Modem Type = USB Modem

Baud = 460800

New PPPD = yes

Modem = /dev/ttyACM0

ISDN = 0

Phone = *99***1#

Password = "blank"

Username = "blank"

Test this with:

sudo wvdial &

You should see the AT commands go past, all followed by nice OK's from the modem, then PPP should negotiate the connection, something like this:

--> Carrier detected. Waiting for prompt.

~[7f]}#@!}!}!} }4}"}&} } } } }%}&MJJI}'}"}(}"C[19]~

--> PPP negotiation detected.

--> Starting pppd at Thu Feb 8 21:05:49 2018

--> Pid of pppd: 848

--> Using interface ppp0

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

--> local IP address 10.170.210.39

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

--> remote IP address 10.170.210.39

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

--> primary DNS address 212.9.0.135

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

--> secondary DNS address 212.9.0.136

--> pppd: ▒[07]R

...and the screen should stop scrolling. Press the enter key to get back to the command prompt and type ifconfig. You should now have a ppp0 connection as well as the usual eth0 etc. To disconnect the PPP link and stop running-up your cellular bill, enter:

ps aux | grep wvdial

You'll get something like:

root 968 0.1 0.3 7228 3444 pts/0 S 21:10 0:00 sudo wvdial

root 972 0.2 0.4 10588 4240 pts/0 S 21:10 0:00 wvdial

root 973 0.0 0.2 3996 2068 pts/0 S 21:10 0:00 /usr/sbin/pppd 460800 modem crtscts defaultroute usehostname -detach user blank noipdefault call wvdial usepeerdns idle 0 logfd 6

Find the task number against the line sudo wvdial and kill that task; in my case:

sudo kill 968

You might have to:

sudo kill 973

...also.

You now have proven cellular connectivity.

I set up web server with the thought that I might want to control the Raspberry Pi that way. Install nginx with:

sudo apt-get install nginx

Enter the local IP address of your Raspberry Pi into a browser and you should see the default nginx page with "Welcome to nginx!" on the top in large friendly letters.

There is a remaining issue in that cellular networks won't generally accept incoming TCP connections (e.g. for HTTP or for an incoming SSH terminal connection). The trick to fix this is to use a reverse SSH tunnel, one where the tunnel listens for TCP connections on the remote machine and forwards them to the Raspberry Pi.

The command you want will be of the following form:

ssh -o StrictHostKeyChecking=no -o "ConnectTimeout 10" -o "ExitOnForwardFailure yes" -o "ServerAliveInterval 30" -N -R xxxx:localhost:yyyy -i /home/username/ioc-client-key -p zzzz user@url

...where xxxx is the listening port on the remote machine, yyyy is the local port on the Raspberry Pi, username is replaced by your user name on the Raspberry Pi, zzzz is the SSH port number (if not 22), user is the username on the remote machine and url is the URL of the remove machine. ExitOnForwardFailure yes is added as, if the ssh client tries to re-establish the connection before the server has realised it has gone and released the port, the tunnel can be set-up but not bound to a port at the server end, in a sort of zombie state. You ALSO need to make sure that, on the server side, you set ClientAliveInterval and ClientAliveCountMax so that, should the connection drop, the server will release the port and it can be re-established (see ioc-server).

If this is for the HTTP connection you probably want xxxx and yyyy to be something other than 80, in which case you must also edit the nginx configuration file /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/default and change the listening port as appropriate (and don't forget to sudo service nginx restart before testing it). Once you've got the tunnel working, for incoming HTTP connections create a file called something like /etc/systemd/system/http-tunnel.service along the lines of the above, test it and enable it to start at boot like the others. Then, on the remote machine, you should be able to open a browser and connect to localhost:xxxx to see the "Welcome to nginx!" page of the Raspberry Pi. If you only have a command-line interface on the remote machine, you can test this with:

curl -i -H "Accept: application/json" -H "Content-Type: application/json" http://localhost:xxxx.

You should do a similar thing to allow SSH/SFTP access for the Raspberry Pi for more direct control. Remember, when you ssh in from the remote machine, to specify the correct port number and your user name on the Raspberry Pi:

ssh -p xxxx -l username localhost

...where xxxx is the listening port you have specified and username is your user name on the Raspberry Pi. You can also retrieve files over the same tunnel with SFTP as follows:

sftp -P xxxx username@localhost:/path_to_file

...where xxxx is the listening port you have specified, username is your user name on the Raspberry Pi and path_to_file is the full path of the file you want to retrieve from the Raspberry Pi. Or you can enter an interactive SFTP session with:

sftp -P xxxx username@localhost

To start up the cellular connection and open an SSH tunnel to the server at boot, you need to create a couple of services. First create the file /lib/systemd/system/cellular.service with contents as follows:

[Unit]

Description=Cellular connection

BindsTo=dev-modem.device

After=dev-modem.device basic.target

[Service]

ExecStart=wvdial

Restart=on-failure

RestartSec=3

StandardOutput=null

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Alias=cellular.service

Note: if you have trouble with wvdial, try temporarily changing the ExecStart line to something like:

ExecStart=wvdial > /home/username/wvdial.log 2>&1

...where username is replaced by your user name, to get log output.

Edit the /etc/udev/rules.d/90-ioc.rules file you created above for the modem device so that it contains:

ACTION=="add", KERNEL=="tty*", ATTRS{idVendor}=="1546", ATTRS{idProduct}=="1102", SYMLINK+="modem", TAG+="systemd", ENV{SYSTEMD_WANTS}="cellular.service"

Test it with:

sudo systemctl start cellular

Your modem should connect to the cellular network and, if you run ifconfig, you should see the ppp0 connection appear. Shut it down again to reduce your cellular bill with:

sudo systemctl stop cellular

To secure your outgoing audio path with an SSH tunnel, create the file /lib/systemd/system/urtp-tunnel.service with contents as follows:

[Unit]

Description=SSH tunnel to server for URTP traffic

Wants=network-online.target

After=network-online.target

[Service]

ExecStart=/usr/bin/ssh -o StrictHostKeyChecking=no -o "ConnectTimeout 10" -o "ServerAliveInterval 30" -N -L xxxx:localhost:yyyy -i /home/username/ioc-client-key -p zzzz user@host

Restart=on-failure

RestartSec=3

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

...replacing xxxx with the local port for the SSH tunnel, yyyy with the remote port on the server for the SSH tunnel, username with your user name on the Raspberry Pi, adding -p zzzz if SSH is not on port 22, replacing user with your user name on the server and host with the IP address/URL of the server.

Before you start the service, cut and paste your finalised ExecStart line and execute it on the command line directly with sudo. This will prompt you to add the fingerprint of the server to the root account.

Now test that the tunnel comes up correctly with:

sudo systemctl start urtp-tunnel

Check on the server end (e.g. by running journalctl -f) that the connection is successful. If you have trouble, add the -vvv switch to the ssh command line above, do a sudo systemctl daemon-reload, start the service again and look at the output on the Raspberry Pi with journalctl -b.

Enable the tunnel to start at boot with:

sudo systemctl enable urtp-tunnel

Reboot and check that the tunnel is open (this will be over Ethernet). If that is successful, enable the cellular service to start at boot with:

sudo systemctl enable cellular

Reboot without Ethernet/wifi connectivity from the Raspberry Pi and check that the tunnel opens over the cellular connection. If you have any issues, use sudo systemctl status cellular and journalctl -b to find out what's up.

FROM NOW ON YOUR CELLULAR MODEM WILL CONNECT AT BOOT AND YOU MUST RUN sudo systemctl stop cellular TO STOP IT. If you want to be sure you don't waste money, disable this until you really need it with:

sudo systemctl disable cellular

...and of course run sudo systemctl stop cellular to stop the current instance. Or just leave the cellular modem disconnected from the Raspberry Pi, to be quite sure.

If you need to open other outgoing tunnelling ports (e.g. to upload log files from the ioc-client) then repeat the process of creating a systemd unit file for the additional tunnels.

Once you have everything running sweetly, create another systemctl unit file that starts the ioc-client at boot by creating a file called something like /lib/systemd/system/ioc-client.service with contents something like:

[Unit]

Description=IoC client

[Service]

ExecStart=/home/username/ioc-client/Debug/ioc-client mic_hw ioc_server:port -g 8 -p 0 -ls log_server:port -ld log_directory_path

WatchdogSec=10s

Restart=on-failure

RestartSec=3

# Simulate stop with CTRL-C for a tidy shutdown

KillSignal=SIGINT

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

...where username is replaced by your user name on the Raspberry Pi, mic_hw is the device representing the I2S microphone, ioc_server:port is the URL where the ioc-server application is running, 8 represents a good maximum gain to avoid noise when there is no input, 0 represents GPIO0, log_server:port is the URL where the IoC logging server is running and log_directory_path is a path where log files can be stored temporarily (probably in a sub-directory of /home/username).

Test that it works with:

sudo systemctl start ioc-client

...and then check its status with:

sudo systemctl status ioc-client

Finally, enable it to start at boot with:

sudo systemctl enable ioc-client

By now, following the instructions here and for the ioc-server and IoC logging server, you will have constructed a system that looks something like this:

+-----------------+ +----------------------+ +-----------------+

| Raspberry Pi | | Linux Server | | Users N |

| | | IoC <---------> HTTP | | HTTP |

| IoC | | | Log | | | | |

| SOu SOl SIs SIh | | SIu SIl SOs SOh SIh | | SOh |

| SSH | +---------+ +--------+ | SSH | | | |

| TCP/IP | | Modem | |Cellular|-------| TCP/IP | ----------------------------- | TCP/IP |

| PPP |--| PPP | \|/ \|/ | | | | +-----------------+

| | | RF |--+ +--| RF | | |

+-----------------+ +---------+ +--------+ +----------------------+

...where 'Sxx' represents a socket and:

- 'Sxu' is the socket for the SSH tunnel carrying URTP traffic (i.e. audio) from the ioc-client application ("IoC") on the Raspberry Pi to the ioc-server ("IoC) application on the Linux Server,

- 'Sxl' is the socket for the SSH tunnel for uploading logs from the ioc-client application ("IoC") on the Raspberry Pi to the ioc-log application ("Log") on the Linux Server,

- 'Sxs' is the socket for SSH control (i.e. port 22) from the Linux Server back to the Raspberry Pi and,

- 'Sxh' is a socket carrying HTTP traffic (two distinct cases of this: one into the Raspberry Pi for Nginx and the other from Users to the Linux Server for HLS traffic).

'x' is either 'O' for outgoing or 'I' for incoming.

The SSH tunnels are there to negotiate the vagaries of cellular networks and to provide authentication/encryption. PPP simply bridges the connection between the modem and the Raspberry Pi. The ioc-server application writes audio files to disk in a form that meets the HTTP Live Streaming standard and serves them to multiple users.

In terms of the dynamic behaviour, all of the stuff on the Raspberry Pi (the cellular connection seen as PPP, all of the SSH tunnels and the IoC client application) will start and restart constantly in order to achieve the steady state of a connection over which URTP audio is streamed. The SSH tunnels can be assumed to be stable once connected. The weak point is, of course, the cellular connection; this may suffer from short or long periods of inability to transport data. The PPP connection will stay up across short (10s of seconds) outages, only dropping when the modem considers that there really is no likelihood of traffic getting through any time soon. And through this malaise the users must get the best possible service. The strategy to do this is as follows:

- The IoC server application will retain a HTTP Live Stream buffer of only the last ~5 seconds of audio. This prevents stale, non-real-time audio from building up.

- The best outcome from cellular connectivity issues is achieved by allowing the cellular standard to do its stuff until PPP finally drops; the IoC client does this by continuing to send, irrespective of success, including re-starting the TCP connection if it drops.

- The SSH tunnels include a keep-alive that is sufficiently regular to keep open the cellular network firewalls etc. but, given (2), don't otherwise pro-actively perform checking of the link.

At least, that's the strategy.

The ioc-client has a parameter -p which will cause it to flash an LED connected to a GPIO line once it is connected and streaming. So that the user gets broader feedback, I created flashyflashy and called this with the same GPIO as I passed to ioc-client but with a slower flash rate to indicate that the Raspberry Pi is alive. To make this simpler I created an environment variable LED in /etc/environment so that everyone can pick up the same GPIO number (so above, where you see the command line option -p 0 to ioc-client, replace it with -p LED). Install flashyflashy and then create a service called something like /lib/systemd/system/led-on.service with the following contents:

[Unit]

Description=Flash LED when up

DefaultDependencies=no

After=local-fs-pre.target

Before=basic.target

[Service]

ExecStart=path_to_flashyflashy LED 1000

Restart=on-failure

KillSignal=SIGINT

[Install]

WantedBy=basic.target

...where path_to_flashyflashy is the path to the flashyflashy executable. Then enable this to run at boot with sudo systemctl enable led-on. Since it's quite nice to know when cellular is connected, I created another of these called /lib/systemd/system/led-on-network.service with the following contents and enabled that to start at boot also:

[Unit]

Description=Flash LED when on-line

Wants=network-online.target

After=network-online.target

[Service]

ExecStart=path_to_flashyflashy LED 100

Restart=on-failure

KillSignal=SIGINT

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

This is not essential, given the SSH tunnelling above, but I decided to set up the Raspberry Pi to use a DDNS account at www.noip.com so that I know its IP address. Do this by configuring a DDNS end point for the Raspberry Pi in your www.noip.com account. Then download and build the Linux update client on the Raspberry Pi as follows:

wget https://www.noip.com/client/linux/noip-duc-linux.tar.gz

tar xzf noip-duc-linux.tar.gz

cd noip-2.1.9-1/

make

sudo make install

You will need to supply your www.noip.com account details and chose the correct DDNS entry to link to the Raspberry Pi.

Set permissions correctly with:

sudo chmod 700 /usr/local/bin/noip2

sudo chown root:root /usr/local/bin/noip2

sudo chown root:root /usr/local/etc/no-ip2.conf

sudo chmod a+rX /usr/local/etc

sudo chmod 600 /usr/local/etc/no-ip2.conf

Create a file named noip.service in the /etc/systemd/system/ directory with the following contents:

[Unit]

Description=No-ip.com dynamic IP address updater

After=network-online.target

After=syslog.target

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

Alias=noip.service

[Service]

# Start main service

ExecStart=/usr/local/bin/noip2

Restart=always

Type=forking

Check that the noip daemon starts correctly with:

sudo systemctl start noip

Your www.noip.com account should show that the update client has been in contact. Reboot and check that the service has been started automatically with:

sudo systemctl status noip

...and by checking once more that your www.noip.com account shows that the update client has been in contact.

If power is removed from the Raspberry Pi before it has shut down there is a chance of SD card corruption. And shutting the Raspberry Pi down in an organised way is not always possible. One way to solve this conundrum is to put all the areas of the file system that must be written to into RAM and then make the SD card read-only. This section describes how to do that based on this advice:

http://blog.gegg.us/2014/03/a-raspbian-read-only-root-fs-howto/

https://www.raspberrypi.org/forums/viewtopic.php?f=28&t=154843

ALWAYS make a back-up copy of your SD card with something like HDD Raw Copy Tool before starting this process so that you can go back to that image in case of boot errors; any misspelling or whatever in /etc/fstab will prevent the Raspberry Pi booting. And of course, with this done, you will need to issue a command to make the disk writeable before you can make any changes (but that's pretty easy, see below).

Open /etc/fstab in your favourite editor. It will look something like this:

proc /proc proc defaults 0 0

PARTUUID=a2ac960e-01 /boot vfat defaults 0 2

PARTUUID=a2ac960e-02 / ext4 defaults,noatime 0 1

# a swapfile is not a swap partition, no line here

# use dphys-swapfile swap[on|off] for that

Edit it to change defaults to ro and change the last number to 0 (to stop file system checks):

proc /proc proc defaults 0 0

PARTUUID=a2ac960e-01 /boot vfat ro 0 0

PARTUUID=a2ac960e-02 / ext4 ro,noatime 0 0

# a swapfile is not a swap partition, no line here

# use dphys-swapfile swap[on|off] for that

...and then append the following:

tmpfs /tmp tmpfs defaults,noatime,mode=1777,size=200m 0 0

tmpfs /var/tmp tmpfs defaults,noatime,nosuid,size=200m 0 0

tmpfs /var/log tmpfs defaults,noatime,nosuid,mode=0755,size=50m 0 0

tmpfs /var/lib/sudo tmpfs defaults,noatime,nosuid,mode=0755,size=2m 0 0

tmpfs log_directory_path tmpfs defaults,noatime,nosuid,mode=0755,size=2m 0 0

...where log_directory_path is replaced by the path to the ioc-client logging directory as specified above. Alternatively, if you care about those logs you could create a separate partition for them or log them to an external USB drive, see below. To check the recursive size of a directory tree in order to verify the sizes in the table above, use sudo du -sh <root>, e.g. sudo du -sh /tmp.

Remove temporary fake-hwclock files by editing /etc/cron.hourly/fake-hwclock and putting the following as the first executable line after the initial comments:

# Switched off in order to set SD card to read only

exit 0

Move logrotate to somewhere writeable by editing /etc/cron.daily/logrotate to add --state /var/log/logrotate.state to its command-line e.g.:

#!/bin/sh

test -x /usr/sbin/logrotate || exit 0

/usr/sbin/logrotate --state /var/log/logrotate.state /etc/logrotate.conf

Disable man indexing by editing both /etc/cron.weekly/man-db and /etc/cron.daily/man-db and putting the following as the first executable line after the initial comments:

# Switched off in order to set SD card to read only

exit 0

Finally, stop the swap file from being used at next boot with:

sudo systemctl disable dphys-swapfile

If you installed noip as described in the DNS section above it will no longer work as it requires its configuration file to be writeable. If you really need it you should follow the instructions below to create an rw area and then move the configuration file with:

sudo cp /usr/local/etc/no-ip2.conf /rw/no-ip2.conf

...then edit the ExecStart entry in the file /etc/systemd/system/noip.service to become:

ExecStart=/usr/local/bin/noip2 -c /rw/no-ip2.conf

nginx suffers from the same problem so, if you installed it as described above then, once you have followed the instructions below to create an rw area, move its configuration file there with:

sudo cp /etc/nginx/nginx.conf /rw/nginx.conf

...then edit the ExecStartPre, ExecStart and ExecReload entries in the file /lib/systemd/system/nginx.service to add the parameter -c /rw/nginx.conf. nginx also seems to have trouble creating its own logging directory, /var/log/nginx, when the directory doesn't already exist in tmpfs, so I added another tmpfs line to /etc/fstab to make it happy:

tmpfs /var/log/nginx tmpfs defaults,noatime,nosuid,mode=0755,size=10m 0 0

Note that the DNS servers, stored in /etc/resolv.conf when DNS sorts itself out at boot, may well be different for your cellular connection and your Ethernet connection. You could make sure that the disk is writeable when you are connected via cellular only, then the correct DNS servers for the cellular network will be stored in the read-only file, otherwise DNS look-up could fail when you are on cellular only. That said, DNS look-up could then fail if you only have Ethernet connected (if the cellular network has its own DNS servers which are only accessible from inside the network), so the better solution is to create an rw area following the instructions below and then move the resolv.conf file to it as follows:

sudo mv /etc/resolv.conf /rw/resolv.conf

sudo ln -s /rw/resolv.conf /etc/resolv.conf

Now take a deep breath and reboot. If the system doesn't boot to a terminal log-in prompt, try attaching a screen and watching for what fails during boot, maybe taking a video of the text scrolling up the screen with your mobile phone (as the vital failed thing might scroll off the top). You might be able to get away with attaching a keyboard to recover but, if not, go back to your backup and try again, remembering that things may have changed in Raspbian over time and so further research may be required to get this right. Try performing the steps above individually, starting from the last one and working backwards, rebooting after each one to determine what's up. Try not setting the partitions to ro and looking at what is failing to mount at boot with journal -b. If you suspect that you've not captured all the things that need to be moved to tmpfs, install the iostat utility with sudo apt-get install sysstat and then run something like iostat -m to find out whether anything has been writing to the SD card (mmcblk0); you want the MB_wrtn entry to show 0. Unfortunately it is not possible to get a per-process view of what wrote to disk as the Raspbian kernel is not built with auditd support, so from here on trial/error and Google are your friends.

If you ever need to write to disk, update any packages, etc., you can easily remount root as writeable with:

sudo mount -o remount,rw /

...or remount boot as writeable with:

sudo mount -o remount,rw /boot

If you wish to have the robustness of the Linux world as specified above but you also want to save your ioc-client log files for later uploading, you should set up a separate partition in which to store them. To do this you will require another Linux machine that you can mount the SD card in as a second drive (or a version of Ubuntu on USB drive with which you can temporarily boot any Windows machine into Linux). The instructions below are based on those here:

https://www.howtoforge.com/linux_resizing_ext3_partitions

Before starting, make another backup of your SD card that you can return to in case of failure. Then take the SD card out of the Raspberry Pi and put it into your other Linux machine.

Run df -h and you should see two new devices in the list, something like:

/dev/sdb2 7583416 2505940 4736720 35% /media/rob/rootfs

/dev/sdb1 41853 21333 20520 51% /media/rob/boot

...and if you run sudo fdisk -l you should see additional information for those devices, something like:

Device Boot Start End Sectors Size Id Type

/dev/sdb1 8192 93236 85045 41.5M c W95 FAT32 (LBA)

/dev/sdb2 94208 15564799 15470592 7.4G 83 Linux

Depending on the number of disks attached to your machine it may come up as /dev/sdc1 and /dev/sdc2, etc. In the remainder of these instructions we will use /dev/sdX; replace the X with the correct drive letter for you.

First we need to shrink the Linux partition, so unmount it with:

umount /dev/sdX2

Remove the journal from that partition (making it an ext2 partition so that resize2fs can run on it) with:

sudo tune2fs -O ^has_journal /dev/sdX2

Then run sudo e2fsck -f /dev/sdX2 to make sure that all is OK. The output should look something like this:

e2fsck 1.42.13 (17-May-2015)

Pass 1: Checking inodes, blocks, and sizes

Pass 2: Checking directory structure

Pass 3: Checking directory connectivity

Pass 4: Checking reference counts

Pass 5: Checking group summary information

rootfs: 115851/474240 files (0.1% non-contiguous), 656263/1933824 blocks

We can now reduce this partition in size; I chose 6 gigabytes:

sudo resize2fs /dev/sdX2 6000M

This may take a few minutes to complete. Take a note of the output, which will be something like:

resize2fs 1.42.13 (17-May-2015)

Resizing the filesystem on /dev/sdb2 to 1536000 (4k) blocks.

The filesystem on /dev/sdb2 is now 1536000 (4k) blocks long.

Now you can delete and recreate the partition to match (with no loss of data). Run fdisk with:

sudo fdisk /dev/sdX

Note: this is run on the disk and not the partition, hence no number at the end.

Press p to print the partition list, getting an output for your partitions something like:

/dev/sdb1 8192 93236 85045 41.5M c W95 FAT32 (LBA)

/dev/sdb2 94208 15564799 15470592 7.4G 83 Linux

It will also give you the sector size in bytes, which you should note (for me it was 512 bytes).

Delete partition number 2 with d followed by 2. Then re-create partition 2 with the commands n, p, 2. Set the first sector to be the same as it was before; in my case 94208. For the end of the partition you need to work out the correct number. From the resize2fs output the size in my case was 1536000 x 4096 bytes, which is 6291456000 bytes. At 512 bytes per sector that comes to exactly 12288000 sectors. Add to this the start sector and I get 12382208. So the end sector is 12382208 - 1, which is 12382207.

Write the new partition information and exit fdisk with the command w. Run sudo partprobe /dev/sdX to re-read the new partition information and then switch journaling back on with sudo tune2fs -j /dev/sdX2.

Now we can create a new partition in the space we have freed up. Run fdisk once more:

sudo fdisk /dev/sdX

...and print the partition list with the command p:

/dev/sdb1 8192 93236 85045 41.5M c W95 FAT32 (LBA)

/dev/sdb2 94208 12382207 12288000 5.9G 83 Linux

Create the new partition with the commands n, p, 3. The start sector for the new partition, from the calculations above, was 12382208 in my case. Accept the default for the final sector (in my case 15564799). Write the new partition and exit fdisk with the command w. Run sudo partprobe /dev/sdX to re-read the new partition information. Now if you run sudo fdisk -l you should see something like:

/dev/sdb1 8192 93236 85045 41.5M c W95 FAT32 (LBA)

/dev/sdb2 94208 12382207 12288000 5.9G 83 Linux

/dev/sdb3 12382208 15564799 3182592 1.5G 83 Linux

Finally, format the new partition with:

sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/sdX3

Put the SD card back in the Raspberry Pi. If you have previously made the root file system read-only, temporarily make it writeable with:

sudo mount -o remount,rw /

Create a mount point for our new partition with:

sudo mkdir /rw

Check that you can mount the new partition with:

sudo mount /dev/mmcblk0p3 /rw

Run sudo blkid to get the PARTUUID of the new partition. In my case the output was:

/dev/mmcblk0p1: LABEL="boot" UUID="CDD4-B453" TYPE="vfat" PARTUUID="a2ac960e-01"

/dev/mmcblk0p2: LABEL="rootfs" UUID="72bfc10d-73ec-4d9e-a54a-1cc507ee7ed2" TYPE="ext4" PARTUUID="a2ac960e-02"

/dev/mmcblk0p3: UUID="90d9322b-9fd8-41ad-921e-8b124a79ed95" TYPE="ext4" PARTUUID="a2ac960e-03"

/dev/mmcblk0: PTUUID="a2ac960e" PTTYPE="dos"

...and hence the PARTUUID I needed was a2ac960e-03.

Now edit /etc/fstab and add the line for the new partition, in my case this was:

PARTUUID=a2ac960e-03 /rw ext4 defaults,noatime 0 0

...just below the other two PARTUUID lines.

Now reboot. Should the reboot fail, connect a monitor to the Raspberry Pi and determine what it is objecting to. You should then be able to put the SD card back into your other Linux machine in order to fix the problem.

Having done all that, create a directory under rw in which to store the ioc-client log files, make the root file system editable temporarily with sudo mount -o remount,rw / then edit /lib/systemd/system/ioc-client.service to match, edit /etc/fstab once more to remove the line which mounted the previous log_directory_path in tmpfs and, to be tidy, remove the old log_directory_path directory and its contents. Reboot again and ioc-client log files should persist in your new directory.

If, during testing, you want the Linux logs to be saved in this zone rather than to RAM disk as normal, edit /etc/fstab and change the line:

tmpfs /var/log tmpfs defaults,noatime,nosuid,mode=0755,size=50m 0 0

...to:

tmpfs /var/log rw defaults,noatime,nosuid,mode=0755,size=50m 0 0

It's probably not a good idea to leave it this way though as it will hammer your SD card.

I had some trouble with the Raspberry Pi not enumerating the modem device properly. Since this is pretty vital, I borrowed from this source to create the following bash script:

#!/bin/bash

# This script resets the named USB modem device on a Raspberry Pi

if [ "$1" = "" ]; then

echo Please give the name of the USB device to be reset, e.g. $0 \"u-blox Wireless Module\"

exit 1

fi

name=$1

directory="/sys/bus/usb/drivers/usb"

if [ $EUID != 0 ]; then

echo This must be run as root!

exit 1

fi

if ! cd $directory; then

echo Failed to change directory to $directory

exit 1

fi

echo Looking for device \"$name\" in $directory...

found=0

for x in ?-* ; do

# Warning: spaces are significant here, don't fiddle with them

y=$(cat $x/product)

if [ "$y" = "$name" ]; then

found=1

echo Peripheral \"$y\" is USB device $x, resetting it...

echo -n "$x" > unbind

sleep 3

echo -n "$x" > bind

echo Reset of \"$y\" completed.

fi

done

if [ $found = 0 ]; then

echo Unable to find \"$name\" on the USB bus.

exit 2

fi

I then made a further script to check for the existence of the/dev/modem device and call my usb_reset.sh script in its absence:

#!/bin/bash

# This script looks for a given device under /dev and, if it doesn't exist, it resets a given USB device

if [ "$1" = "" ] || [ "$2" = "" ]; then

echo Please give the name of the device to look for and the USB device to reset if it is not there, e.g. $0 \"modem\" \"u-blox Wireless Module\"

exit 1

fi

if [ ! -e "/dev/"$1 ]; then

echo Device \"$1\" does not exist, resetting \"$2\"...

/home/rob/usb_reset.sh "$2"

fi

I made both scripts executable with sudo chmod +x. Then I made another couple of systemctl unit files; first /lib/systemd/system/check_modem.service:

[Unit]

Description=Check that the modem device exists and, if it does not, reset the USB modem device

[Service]

Type=oneshot

Environment="DEVICE=modem" "USB_DEVICE=u-blox Wireless Module"

ExecStart=/home/rob/check_modem.sh ${DEVICE} ${USB_DEVICE}

...then /lib/systemd/system/check_modem.timer:

[Unit]

Description=Run check_modem service periodically

[Timer]

OnUnitActiveSec=30s

OnBootSec=30s

[Install]

WantedBy=timers.target

This has the effect of running the modem device presence check every 30 seconds from boot. I started the timer with sudo systemctl start check_modem.timer, enabled it from boot with sudo systemctl enable check_modem.timer and checked that it was running with sudo systemctl list-timers --all:

NEXT LEFT LAST PASSED UNIT ACTIVATES

Tue 2018-05-22 23:10:13 UTC 27s left Tue 2018-05-22 23:09:42 UTC 2s ago check_modem.timer check_modem.service