___ _ __ _ _ ___| |_

/ __| '__| | | / __| __|

| (__| | | |_| \__ \ |_

\___|_| \__,_|___/\__|

'crust' - Learn the basics of Rust and C side by side.

Here, I'll document my hurdles in learning Rust and utilise whatever knowledge I have in C. This repository must not be treated as a base for the upcoming publication of a top-selling ePub for the Rust programming language. As of today, 2022/10/14, the tutorial 'crust' is in its early stages. It is expected that 'crust' will undergo perennial refinements. I'll try to keep things as simple as possible so that anyone within the age group 10 to 15 can learn elementary-level Rust and C. Adults should also find the tutorial easier than the programming books recommended in their high school/pre-university curriculum. Things are expected to be short since I may have to look back. If possible, the learning sessions will be translated into the Bengali language. Auto-translation software will be used to translate the documents into Bengali. Grammar-checking services will be used occasionally in the English versions. Please create a pull request in the GIT branch 'rough' if you want to improve the learning experience or if you have a suggestion.

Your active participation might help hundreds of newcomers to learn the concept of coding. The flow of logic and algorithms are almost the same across programming languages. I want you to participate. I'm not interested in any indirect involvement.

Don't expect any long introduction, since I don't have time for that. I have to keep things short. Don't expect eBooks in ePub or HTML format at the moment. However, an auto-generated HTML version of the documents will be provided from time to time.

Please have a look at Tulu-C-IDE.

You will find instructions to set up the MSYS2 Build Environment in detail. Leave the Installation directory up to the MSYS2 installer (The default location is: C:\msys64). For consistency, we won't be using the "Microsoft Visual Studio Build Tools" (a.k.a., Windows SDK) or the IDE version of the MSVC (a.k.a., Visual Studio). If you want to install MSVC, go ahead and do so. Examples provided here will compile either with MinGW (a variant of GCC that you can find in the MSYS2 repository) or MSVC. However, you're on your own if you choose MSVC; make sure you set up the Microsoft build environment properly through the Microsoft-provided vcvarsall.bat.

I do not recommend a full-blown IDE like Visual Studio, QT Creator, KDevelop, Code::Blocks IDE, CodeLite IDE, or Eclipse CDT unless you have very specific requirements to run a particular IDE. You won't need any of them, at least for now.

To keep things simple and make the journey a hands-on experience, do not use the autocompletion feature in any of the editors mentioned. However, you are allowed to use those editors mentioned with their configurations (Tulu-C-IDE and Tulu-C-IDE Helix Edition). You can look at the autocompletion hints, but type the code yourself. In my opinion Tulu-C-IDE Helix Edition will be a better choice for learning. Type the codes yourself. Or else, you'll learn nothing. I mean, be a little honest with yourself. Don't cheat yourself.

The more you will type the code yourself, the less you'll forget what you've learned. If you are on MS Windows, try Geany or Notepad++. On Linux systems with GTK-dependent Desktop Environments, such as GNOME, XFCE, MATE, Cinamon etc., you can use Geany. If you are using a Linux distribution that ships a QT-based Desktop Environment, for example, KDE, LXQT etc., try Kate. Like Geany, Kate can be installed on MS Windows.

Kate comes with built-in LSP support. Thus, if Kate finds the two files .ccls and compile_flags.txt, you'll see autocompletion hints. So, beware and don't use autocompletion. Autocompletion is useful when you have some familiarity with the language, not at the time of learning. Nevertheless, Kate is also a text editor of choice among professionals and serious hobbyists for code editing. It works like a charm on my MS Windows 10 machine, my primary (work) computer.

Download the entire repository in a Zip archive. Extract the zipped file somewhere on your hard drive. Remember that the location (path to the directory where you want to extract the archive) must not contain any space or special character other than underscores (i.e., _). Examples: G:\test_n_practice\crust, /home/YOUR_USERNAME/crust/.

Enter crust/ from the graphical file manager. R-Click inside the folder and find the option to open a terminal emulator there. Open two terminal emulators if you are on Linux, one for editing the source file with Helix and the other for compiling/executing the code. Type ls (Linux) or dir (Windows) to see the contents of the folder. You'll find runc.sh that you can use on most Linux systems to build/run the code. Use runc.BAT or runc-msys2x64.sh on MS Windows machines. You don't have to open a separate console. Double-click on the DOSBATCH script and it will take care of the build process. Or, use the script runc-msys2x64.sh with the "MSYS2 MinGW 64-bit" Bash Shell.

# Change the execution permission parameter of the script.

chmod +x runc.sh

# Run the script.

./runc.shModify the files main.c and main.rs in crust/code/testbed/src/ along the way. You'll keep backups in a plain text file.

Find a file exercises.txt. After learning a particular topic, write the code and notes to exercises.txt on the topic you covered.

FAQ: Can I use the Power Shell? Yes, but it doesn't have any purpose here. Build chains are largely driven by makefile generators (CMake, Bakefile), make utilities (make, nmake, mingw32-make), and build environments (Cargo), regardless of the complexity of the project. Both theoretically and technically, any console interface can be used. Although, using the PS might involve unnecessary work sometimes. Look at this Stack Overflow thread. Instead, use an emulator like WezTerm and switch to the PS from there when required. For compiling C/C++/Rust projects, the more feature-rich, objected-oriented Power Shell language is not a requirement. The right tool for the right job matters the most without drifting away from the task at hand.

- Hello, World! The Skeleton and its Anatomy

- Receiving Inputs

- The Character Set

- Reserved Keywords

- Constants, Variables, and Keywords

- Data Types and Variables

- Data Types

- Variables

- Constants

- Characters and Strings

- Operators

- Rules for Constructing Instructions

- Decision Control

- Loops & Flow control

- Case Control

- A Brief Description of Pointers (C) and Slices (Rust)

- Functions and Pointers

- Tuple - A Rust-Specific Compound Data Type

- Array

- More on Arrays, Tuples, and Vectors

- Strings and Vectors

- The Preprocessor in C

- Ownership and Borrowing in Rust

- Ownership

- Borrowing

- Structures

- Unions

- Enums

- Modules

- Collections in Rust and The C Standard Library

- Error Handling in Rust

- Rust's Generic Data Types

- Console Input and Output

- Operation on Files (Input/Output)

- Type Inference and Type Casting

- Renaming Data Types and Typedefs

- Typecasting

- Bit Fields

- Pointers to Functions

- Functions Returning Pointers

- Functions with Variable Number of Arguments

- Unions

- Union of Structures

- Package Manager

- Iterator and Closure

- Smart Pointers

- Concurrency

- fork(), exec(), pthreads(), Multithreaded Programming

- Copyright Notice:

C:

#include <stdio.h> // Inclusion of header files.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <math.h>

// This is how we write a single-line comment.

/* This line is also a single-line comment. */

/*

This is

a

multi-line

comment

*/

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { // The compulsory main() function.

printf("Hello, C!\n"); /* printf(),

a function that outputs formatted strings to the console. */

} // End of the code block (here, the block is the function main()).Rust:

// Notice that you don't need to include a header file.

fn main() { // main() is a compulsory function even in Rust.

println!("Hello, world!"); /* println!() is a macro

which is used to send formatted strings

to the console.

Notice that this line is also

a multi-line comment.

*/

} // End of the code block (here, the block is the function main()).Comments are areas of code ignored by the compiler.

One who writes the code keeps pieces of information under comments as hints for what the code does in a specific section so that the logic of the code becomes easier to understand and stays maintainable in the future.

Comments in both C and Rust are enclosed within /* */. Another style of writing a single-line comment is to write // before writing the comment. // Single-line Comment. Anything after the // part is ignored by the compiler. Usually, // comments are used as End Of The Line Comments or simply 'Line Comments'. We use // where we don't need to write any code after the comment part. Whereas, /* */ can be used as inline comments, e.g.,

fn /* comment */ main() {

}// Line comments which go to the end of the line./* Single-line/Multi-line/Inline comment */fn main() { //main() is a compulsory function even in Rust (a comment indeed).

// ...

// ...

}Multi-line Comments or Single-line/Multi-line/Inline/Universal Comments:

Comments enclosed within /* */ can be split across lines.

/*

This is

a

multi-line

comment

*/Doc comments in Rust: Doc comments are parsed into HTML library documentation:

/// Generate library docs for the following section.

//! Generate library docs for the enclosing section.We will restrict ourselves to 1) End Of The Line Comments, // and 2) Multi-line/Universal Comments, /* */.

A block of code or Code Block is a lexical structure of instructions grouped together comprising declarations, operators, and statements. Foxed?

Don't be! For now, remember that a code block is something grouped within brackets, e.g., {}.

{ // an example of the start of a block of code

} // an example of the end of a block of codeSimply,

{

}In our Rust Hello World example,

fn main () {

// ...

// ...

}Here, the function main() keeps its set of instructions within a block of second brackets {}.

In C & Rust, main() is the driving force of all programs. Every program that executes must have a main() function that initialises the program execution.

All major programs you run on your machine are compiled from several source files. Each source file may contain thousands of lines of code. However, the function main() initialises the program execution. main() serves as an Entry Point to the program's startup.

The main() appears only once, no matter how large the project is. In case you are isolating parts of the program into multiple shared libraries (*.dll or *.so), each shared library can be driven by its individual driving function DllMain(). On the other hand, it is not mandatory to create a DLL Entry Point for creating a shared library. We will cover the creation and use of Shared Libraries and Static Libraries in C later.

#include <windows.h>

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(

HINSTANCE hinstDLL, // handle to DLL module

DWORD fdwReason, // reason for calling function

LPVOID lpvReserved ) // reserved

{

// Example code for a DLL Entry Point function.

// Look here for more info:

// https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/dlls/dllmain

}For now, remember that every program you write needs a main() function.

#include <stdio.h> includes a text file stdio.h containing some routines, such as text input/output to the console. It (stdio.h) is basically a plaintext source file. #include <> is used to attach source codes. It is called the Include Directive in C. The Include Directive is also a macro. We will visit the section of macros later. We will have to revisit it quite a few times.

What does the file stdio.h do here, should be our question at the moment. It contains routines for text input/output to the console and some other routines. Compiler writers supply pre-defined routines prescribed by the ISO C standardisation committee for common tasks. Libraries outside the Standard C Library are also used for special purposes, such as Graphics, image/video processing, Graphical User Interface, dealing with intricate mathematical problems, scientific/business application programming etc. In our Hello World example in C, we used the pre-defined function printf() for text output to the console.

Notice that we didn't include any standard library header like stdio.h in our Rust Hello World program.

Functions are called the building blocks of programs. A function contains a set of routines to accomplish a particular task. Think of a car assembly line where every section plays different roles, and those who work in each department in the assembly line take their own part, making each department a complete set but also an independent part of the entire workforce. Think of functions as departments in that assembly line. Functions can also be compared to Bricks that are used in construction works. Your room contains hundreds of bricks.

The function pow(x,y) returns x raised to the power of y i.e. x^y (x to the power y). pow() is declared and defined in the C standard library math.h.

We included stdio.h to call the function printf(). It is used here for sending text output to the console.

MACRO: The Search-n-Replace utility in the compilers.

To be precise, 'Macros' are a group of characters to be replaced by the compiler with another predefined set of characters at the stage known as 'Preprocessor'. Macros and Preprocessors will be discussed later.

#define ADD_TWO_NUM (a, b) (a) + (b)#defile MAX_VALUE 1000Macros in C always start with the symbol #.

ADD_TWO_NUM(a, b) (a) + (b)ADD_TWO_NUM(8, 3)#include <stdio.h>

#define ADD_TWO_NUM(a, b) (a) + (b)

int main() {

int u = 2;

int v = 3;

printf("%d\n", ADD_TWO_NUM(u, v));

return 0;

}gcc test.c -o test.exe

test.exe

5

How macros get expanded:

gcc -save-temps -c test.c

gcc -E test.c > test.i

test.i

# 5 "test.c"

int main() {

int u = 2;

int v = 3;

printf("%d\n", (u) + (v));

return 0;

}Look how the macro ADD_TWO_NUM(a, b) got expanded to (u) + (v). Somewhat similar to a search-n-replace utility!

The Four Stages of Compilation in C:

Compilation: Compile is a process of transforming source codes into machine language that computers speak. The process of compilation passes through four stages.

-

Preprocessor (Compiler-generated Intermediate C/C++ File,

test.c->test.i.) -

Compiler (Assembly Language Code,

test.i->test.s.) -

Assembler (Assembly Language Code to Relocatable Object Code,

test.s->test.o.) -

Linker (All Relocatable Object Code Files to Machine-Readable Native Executable Code,

test.o->test.exe.)

Compilers' primary job: A Compiler is a program/piece of software/utility/application that turns source codes into machine-native binary executable files.

Extra Features: Beside performing designated task of translating source codes into machine native executable files, compilers may provide other facilities such as error checking, detection of runtime error, memory leak detection, Language Server Protocol for autocompletion etc.

Stage 1 (Preprocessor):

gcc -E code.c > code.i

In this stage, the compiler toolchain performs the following tasks:

-

Comment stripping: The compiler toolchain strips all comments and replaces them with single spaces.

-

Header inclusion and producing text blobs: The compiler toolchain attaches (includes (

#include< >)) the instructions written in the header files (*.h) and creates a single blob of text. -

Macro expansion: The compiler toolchain expands predefined macros.

Here, in this stage, the compiler takes all source files and generates individual intermediate text blobs (*.i). Those blobs contain routines declared in header files attached to your source codes using the include directive #include < >.

Stage 2 (Compiler):

gcc -S code.c > code.s

In this stage, the compiler toolchain transforms the preprocessed text blobs (*.i) into Assembly Language codes (*.s).

Stage 3 (Assembler) :

gcc -S code.c > code.o

Now the toolchain translates the assembly language codes into relocatable object codes (test.o) that are still needed to be resolved by the linker. Relocatable Object Code files are not human-readable.

Stage 4 (Linker):

gcc code.c

In this stage, a separate program (in GCC/MSVC) in the toolchain called "Linker" takes all the Relocatable Object Code (*.o) files and semi-compiled routines (functions etc.) from externally linked static/dynamic libraries (GUI, Graphic, Image Processing, Compression, Cryptography etc.). The linker must be told to search for those semi-compiled external files from specific locations along with the names of the libraries to be linked. We will come to Static and Dynamic Libraries later.

A brief overview:

Preprocessor Stage: For example, if your project contains three source files one.c, two.c, three.c, the compiler will first generate one.i, two.i, three.i. Assembler Stage: The compilation process will now pass through the Assembler which will translate the raw C codes (intermediate files, *.i) into Assembly Language code files. Namely, *.s. Compiler Stage: Then, those intermediate files will be converted to relocatable object code files one.o, two.o, three.o. Linker Stage: In the next stage, the compiler will search for object code files (semi-compiled) libraries you used in your project. By combining all relocatable object code files the compiler will produce a final executable file.

If you've set up your project to split the program into separate Shared Library files and executable files, then the final rendition will contain Shared Libraries and executable files.

Rust however works in a slightly different manner.

-

Invocation:

-

Lexing and Parsing:

-

High-Level Intermediate Representation (HIR) Lowering:

-

Mid-level Intermediate Representation (MIR) Lowering:

-

Code Generation:

[Citation needed.]

Invocation: First, the Rust compiler (rustc) is invoked by Cargo or directly by the user. The toolchain processes command-line options for optimisations and other tasks, such as installing the program after completing the build process. In this stage, rustc performs check-only builds (rather than producing executable machine code) with the help of rustc_driver.

Lexing and parsing: The raw Rust source text is analysed by a low-level lexer. The lexer turns the source code into a stream of atomic code units which are called tokens. rustc_parse takes the charge of passing the stream of tokens through a higher-level lexer. Macros get expanded. A set of validations is checked by the StringReader Struct and turn strings into interned symbols (Not our business. It is a way of storing only one immutable copy of each distinct string value). The parser translates the stream of tokens from the lexer output into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). Some intermediate files are generated that can be found in the rustc_parse directory. For example,

expr.rs

pat.rs

ty.rs

stmt.rs

High-Level Intermediate Representation (HIR) Lowering: The Rust compiler collects the AST. The AST is converted to a more compiler-friendly representation called High-Level Intermediate Representation (HIR). The process of translating AST to HIR is called "lowering". We will learn the types of variables in C and Rust. In short, a variable type is like a unknown quantity in regular mathematics, x,y,z,u,v,r etc., except, the variable type must be declared to inform the compiler beforehand. A variable can be of an integer type (1, 5, 99, 1567, etc.), floating value (2.05, 7.01, 39459.04567 etc.), or a string of characters (Abracadabra, Smiley emoji, Your Name, a, b, c, d etc.). Other variable types also exists. Now, the compiler uses the HIR to do type inference. Type interface is the process of automatic detection of the type of an expression. A few more tasks are performed, like trait solving, and type checking.

Mid-level Intermediate Representation (MIR) Lowering: The compiler now translates the HIR to Mid-level Intermediate Representation (MIR), used for borrow checking. Rust also constructs the THIR, which is used for pattern and exhaustiveness checking. Some optimisations are performed. In my limited understanding of the internal working principles of the Rust compiler, it is a one-step extra refinement of the HIR.

Code generation: A process known as codegen begins at this stage. It is the stage when higher-level representations of the source performed in the earlier stages are turned into a machine-native executable. rustc converts the MIR to LLVM Intermediate Representation (LLVM IR). It is done by LLVM software. LLVM stands for Low Level Virtual Machine.

We don't have to understand most of the Rust compiler stages to understand Rust programming. It is how Rust works in the background. As long as we are able to build our project using Cargo, we won't pull open the bonnet.

Programming Languages and Compilers: Remember that Programming Languages are sets of rules defined by a committee, and Compilers are programs that follow their guidelines. Different compiler vendors can make different compilers as long as they follow the same guidelines. Much like "the Shops and Establishments Act" that empowers you to open a shop but you'll have to follow the law. You cannot do whatever you want in your shop because you run the shop. Every financial institution have to abide by the rules mentioned in "the Companies Act". Similarly, you can drive a car as long as you follow the traffic rules. One compiler may give you some advantages over others. However, the rules formed by the organisation that standardises the guidelines, a.k.a., the standardisation committee, must be followed by the compiler vendor.

Enough about macros and the working principles of compilers, let's come back to macros in Rust.

Here, in our Rust Hello World example, println!() is a macro. Unlike printf() in C, it is not a function.

Notice the NOT/ Exclamation mark (!) after println. In Rust, macros are denoted by an ! mark at the end of the macro before using it. We don't have to look under the bonnet to discover how Rust expands println at the moment. What is crucial for us to know right now is the use of the println!() macro for text output in the console in Rust. One important note, text input/output is called formatted string input/output in C and Rust.

More about macros later.

printf("%d\n", ADD_TWO_NUM(u, v));println!("Hello, world!");;

Every instruction/command in C/Rust is a Statement. The end of the statements must be denoted by a semicolon, ;. A C/Rust function, a macro in Rust in a block of code, are examples of individual statements. Notice the use of semicolons in the upcoming chapters.

Let's Break Another Skeleton:

It will be easier to start with C.

Area of a Circle.

/*

A C program to calculate the area of a circle.

*/

// https://byjus.com/maths/area-of-circle/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

#define PI 3.14 // 22/7 = 3.14 (approx.)

int main(void) {

float radius = 0;

float area = 0;

printf("Type the value for the radius of the circle and hit Enter:\n");

scanf("%f", &radius);

printf("Radius = %f\n", (double)radius);

area = (float)(PI * (pow((double)radius, 2))); // The formula: area = pi * r^2

printf("Area = %f\n", (double)area);

return 0;

}We've already discussed the include directive. You can attach any source code in text format with an extension that the compiler recognises, e.g., #include <math.h>. The files you attach contain some pre-defined routines that save you time. You can call a function without having to write it from scratch. We've also discussed that the Include Directive is a macro.

#define PI 3.14 is a Preprocessor Directive (macro) that replaces PI with 3.14 wherever it finds PI inside the code section.

int main(void) {

area = (float)(PI * (pow((double)radius, 2))); // The formula: area = pi * r^2

}As we saw earlier, every program must have a main() function that initiates the program. A function contains a series of instructions inside that function block. Besides that, a function can return a value or return nothing (void). int main() means that the main() function returns an integer value upon completion, after going through all instructions. int main(), In this case, the value has to be either ZERO (0) or ONE (1). If the main() function returns Zero, that means the function has completed successfully, and encountered Zero errors. When a function is intended to return nothing, it is written as void function_name(), or void *function_name(), or void **function_name() etc. However, ISO C Standard Committee specifies that the main() function is not allowed to return a void value. void: It denotes a non-existing value. Don't write void main().

Is void main() strictly forbidden and illegal? Yes. However, like all rules, there are exceptions. You'll find void main() in codes written for embedded systems in many instances. Most microcontroller vendors also sell their own version of C compilers targeting that specific platform (controller ICs). They don't strictly follow that int main() rule. The programs we run on our PCs, servers, and peripherals run on top of an operating system. In embedded systems, more often than not, there is no operating system to collect that return value from the main(), even if the main() function returns a value. Moreover, embedded systems are designed to run indefinitely unless a power interruption is encountered. So, it is crucial for the code that executes on those systems to be free from any runtime error and the main() function doesn't have to stop itself anyway. A return value is purposeless in either of the cases. Nevertheless, it is a good practice to follow conventions and write int main() in codes written for embedded systems.

Function parameters: A function can take values for performing a task. For example, double sqrt(double x) is a standard C library function found in math.h. What does this mean? A double is a data type used for storing high-precision floating-point numbers in memory registers. Everything we do on our computers involves memory operations. We will come to float and double later. The function sqrt() returns a fractional number in the range of 1.7E-308 to 1.7E+308, which is 8 bytes. E is a scientific notation that stands for Exponent of 10 (the power of 10). 2.54E16 means sqrt() we see that it takes a value of the size of double. x is a variable that is used for holding the value in memory before passing it to the internal instructions of the function sqrt(), that is, sqrt(double x). So, the function takes a fractional number (float/double) through sqrt(double x) and returns the result which is also a fractional number (float/double), double sqrt(). How to use that function?

double hypotenuse = 0.0;

double side1 = 16.238;

double side2 = 20.552;

hypotenuse = sqrt((side1 * side1) + (side2 * side2));

printf("Hypotenuse: %lf\n", hypotenuse);Pythagorean Theorem:

Another way to use the function sqrt():

double result = 0.0; // initialising the variable

double fixed_fractional_value = 100.00;

result = sqrt(fixed_fractional_value);

printf("Result: %lf\n", result);Now it is clear that a function can take some value as arguments and return a value. An important note: A function is allowed to return only one value. Thus, a function can receive no value (void) and return a value upon completion. A function (other than the main()) can take arguments as pointers (we will visit a dedicated chapter on pointers), performs a task, and return the result alternatively via the received pointers without returning anything through a regular return parameter, void function_x(int *integer_value, char *a_string, float fractional_no).

So, the structure is:

return_parameter function(argument_one, argument_two, argument_three, argument_four, arg_so_on) Or, in better words,

data_type function(data_type variable1, datatype variable2, data_type pointer, data_type_so_on_so_forth)Or, in better words,

int/char/float/double fn(int var1, float *var2, double *var3, char **string)Etc.

Our main function is allowed to either receive two parameters main(int argc, char *argv[]) or receive nothing main(void). It is allowed to leave the argument section blank, main(). In case it is left blank, main() will not receive any value. Now ask me what is the purpose of receiving arguments through the main() function. What did you type in the console to obtain the assembly language output of your first code? gcc -S code.c > code.s, right? gcc, the compiler, is a program. -S and code.c are arguments. The console (e.g., CMD.EXE) you are using is a program,> is the argument that tells it to redirect the output to a file code.s (that too is an argument). In the first chapters, we will restrict ourselves to int main(void), so no worry!

float radius = 0;

float: Float is a datatype for storing fractional numbers. In C, a fractinal number is either a float or a variant of it, such as double. double means long float which can store bigger numbers than float. These are called floating point numbers. float usually has a storage size of 4 bytes. It is a 32-bit IEEE 754 single precision value in the range of 1.2E-38 to 3.4E+38 with precision up to 6 decimal places. You may ask me about the purpose of so many data types. Nothing is unlimited. Our computers have a finite amount of memory, no matter how big it is. Then, there must be a way for the Assembler to determine the size and type of a variable to make the code able to work step by step internally, which is unrelated to the size of your computer memory.

Storage Class and Data Types will be discussed later. We'll deal with five data types, int, variations of int, float, double, char primarily, although all Data Types will be covered.

Here, we will be using the variable radius (a fractional number) to store the result of the calculation in our code to get an output. float radius is the part that deals with variable declaration. First, we write the datatype (here, float), then we give our variable a name, radius.

There are rules for declaring variables which we will see in a dedicated chapter on variables. For now, remember that a variable name must not start with a Capital Letter, Number, or a Special Character other than an underscore. Only small letters and underscore are allowed to be placed in the beginning of a variable name. Special Characters and Blank Space cannot be used anywhere in any naming (variable, structure, function etc.) convention. Numbers and Capital Letters can be used after writing the variables' initial characters legitimately. We will come to it later.

Legal:

int variable, int _variable, float variable01, float variable_01, char stringVariableTwo

Illegal:

int Variable, float 01variable, int v@r!able, float variable 01

Variable Initialisation: The compiler must have some idea of the value a variable is holding at any moment in the process of execution. If the compiler doesn't find a value, it will create one. The automatic variable initialisation creates a randomly generated value which is known as Garbage Value. A garbage value will produce unintended result. If the compiler doesn't create a value for an uninitialised variable, the code will try to access a memory location that doesn't exist. The program will crash, leading to unprecedented consequences. It is also a strict rule to initialise the variable immediately after declaring it (C & Rust), or initialise the variable before accessing it (C). By writing float radius = 0, we initialise the variable immediately after the variable declaration.

Have some Fun: Semicolon: ;

Don't forget the use of semicolon (;). In a lot of situations I tried to figure out what went wrong with the code and found that a missing semicolon was preventing the compiler from compiling the code. Finding such pesky omissions is finding a needle in a haystack. Nip those small silly oversights in the bud.

Assignment Operators: = is an Assignment Operator that binds a value to a variable.

NOTE: It has very little to do with the = means giving a variable a value; simply pouring some water into a glass. The sign = is not used for comparison in C. We will discuss Operators in the relevant chapter.

printf("Type the value for the radius of the circle and hit Enter:\n");printf() is a standard library function (int printf(const char *format-string, argument-list)) declared in the header file stdio.h that takes two arguments in the format (const char *format-string, argument-list) and returns an integer value after completion.

const char *format-string means the the first argument (before the comma that separates it from the second argument) takes a formatted string specified by the string conversion specifications in the C programming language.

A bit more on format specifiers:

Before we dive into examples, let us declare variables:

Know the number of bytes a datatype can store. Examples:

printf("Size of int is: %llu\n", sizeof(int));

printf("Size of unsigned int is: %llu\n", sizeof(unsigned int));

printf("Size of short is: %llu\n", sizeof(short));

printf("Size of char is: %llu\n", sizeof(char));

A bit can store 2 values (0 and 1).

8 bit 1 byte. Conversely, 1 byte 8 bit.

An int can store 4 bytes, or simply,

That means, 2 values (0 & 1) multiplied by 32 (per byte)

When a variable is signed, the most significant bit is reserved for the sign itself reducing it to the total capacity minus one. 0 denotes a positive number, and 1 denotes a negative number, thus, making the room available for a signed int in the range of -2^31 to 2^31-1, and for the unsigned ones 0 to 2^32-1. Do you have the Microsoft Calculator installed on your computer. Go to the Scientific Calculator Mode and find the value of 2^31. It is 2147483648. The range of a signed int (or int) is -2147483648 to 2147483647. The range of an unsigned int is 0 to 4294967295. I use the MATE Calculator on my Ubuntu XFCE machine. On Ubuntu GNOME, you'll find the GNOME Calculator. Most modern calculators have a scientific mode.

int an_integer = 10;

float a_fractional_no = 11.3268;

float a_bigger_fractional_no = 11238879.2675468746768768713;

long int a_big_integer = 123669788445664446;

long int a_big_integer = 12366976; or, simply long a_big_integer = 12366976;

long long int a_very_big_integer = 123669765464787971;

unsigned int a_non_neg_no = 42949672;

long unsigned int a_non_neg_big_no = 1844674405;

char a_sentence[26] = "Abracadabra in a sentence!"; or, char a_sentence[] = "Abracadabra in a sentence!";

double _expo = 5.2376e+02;

Try it yourself.

Template:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

long long int a_very_big_integer = 123669765464787971; // Initialised the variable

printf("Size of long long int is: %llu\n", sizeof(long long int));

printf("%lld", a_very_big_integer); /* Prints the initialised value */

return 0;

}Output:

Size of long long int is: 8

123669765464787971

| Format Specifier | Description | Data Type (unless Not Applicable) | Examples | Size (in Bytes) | Range (on a 64-bit compiler) | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

%% |

Prints the % sign itself. |

N/A | printf("%%"); Output: % |

|||

%d or %i |

Prints a signed integer. 10, -3 etc. |

int |

printf("%d", an_integer); Output: 10 |

4 | -2147483648 to 2147483647 |

|

%ld |

Prints a long signed integer. | long int |

printf("%ld", a_big_integer); Output: 12366976 |

8 | -9223372036854775808 to 9223372036854775807 |

|

%lld |

Prints a long long signed integer. | long long int |

printf("%lld", a_very_big_integer); Output: 123669765464787971 |

8 | -9223372036854775808 to 9223372036854775807 |

|

%u |

Prints an unsigned (non-negative) number. | unsigned int |

printf("%u", a_non_neg_no); Output: 42949672 |

4 | 0 to 4294967295 |

|

%lu |

Prints an unsigned (non-negative) long integer number. | long unsigned int |

printf("%lu", a_non_neg_big_no); Output: 1844674405 |

8 | 0 to 18446744073709551615 |

|

%f |

Prints a mid-range floating-point (fractional) number. | float |

printf("%f", a_fractional_no); Output: 11.326800 |

4 | 1.2E-38 to 3.4E+38 |

Up to 6 decimal places. |

%lf |

Prints a double which can hold bigger values than float (also a floating-point [fractional] number). [double means long float.] |

double |

printf("%lf", a_bigger_fractional_no); Output: 11238879.000000 |

8 | 2.3E-308 to 1.7E+308 |

Up to 15 decimal places. |

%Lf |

long double |

16 | 3.4E-4932 to 1.1E+4932 |

Up to 19 decimal places. |

||

%c |

Prints a single character (an alphabet). 'A', 'm', 'W' etc. | char |

printf("%c", _one_alphabet); Output: W. |

1 | Signed: -128 to 127. Unsigned: 0 to 255. |

|

%s |

Prints a string of characters. "A Sentence." | char |

printf("%s", a_sentence); Output: Abracadabra in a sentence! |

1 byte per character | Depends on the size of the string length. | |

%e |

Prints an Exponential notation ( small 'e', 2.9738e+00) |

float or double |

printf("%e", _expo); Output: 5.237600e+02 |

|||

%E |

Prints an Exponential notation ( Capital 'E', 2.9738E+00) |

float or double |

||||

%g |

A more compact version of %e or %f. Insignificant zeros are omitted. |

float or double |

||||

%G |

Same as %g, with a Capital E. |

float or double |

Conversion Flags:

How many digits do you want to print, and how many decimal places do you want in the fractional values?

| Flag | Instruction | Example | Description | Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|

+ (Plus sign) |

Must print a sign character (+ or -). |

%+3.4d |

1) The minimum number of digits to be printed (%3d). 2) The number of digits to be printed after the decimal point (usually a Full Stop ASCII character). %3.4f will print fractions up to four decimal places. |

1) Field width. 2) Precision. |

- (Minus sign) |

Same as above, but Output the converted argument as Left-justified. | %-3.4d |

Do | Do |

0 (ZERO) |

Fill (called 'pad') with Zeros instead of spaces. | %03.4d |

Do | Do |

# (SHARP or HASH) |

Print an alternate form of the output. (Not our concern at the moment for learning C.) |

| Escape sequence | Activity |

|---|---|

\n |

Prints a New Line character. |

\t |

Prints a TAB character. |

\b |

Backspace (non-erase) |

\\ |

Prints a Backslash. |

\" |

Prints a Double-Quote, ". |

\' |

Prints a Single-Quote, '. |

\f |

Form Feed/Clear The Screen. |

\a |

Bell Sound (plays a speaker beep). |

\r |

Carriage Return. (Enter). |

\v |

Vertical tab. |

\? |

Question mark. |

\xnn |

Hexadecimal character code nn (Not our concern). |

\onn |

Octal character code nn (Not our concern). |

\nn |

Octal character code nn (Not our concern). |

The Return Value of printf():

Upon successful completion, printf() returns the number of bytes (int) it printed.

How will you print " using printf()? Simple!

\"

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("Regardless of how intimidating\n");

printf("it seems in the beginning,\n");

printf("programming in \"C & Rust\" is\n"); // Notice the use of \" to print "

printf("a piece of cake in the end.\n");

return 0;

}Regardless of how intimidating

it seems in the beginning,

programming in "C & Rust" is

a piece of cake in the end.

You printed "C & Rust" using printf().

We've learned something about the printf() function. Time to break down our code.

printf("Type the value for the radius of the circle and hit Enter:\n");printf("") is the minimum form of the printf() function. You can write printf(""); in a line as a complete statement. Even then, the compiler will show you some warning messages like warning: zero-length gnu_printf format string [-Wformat-zero-length]. That means anything you want to print to the console must be enclosed within a pair of double quotes, "". In C, a character/string is always surrounded by a pair of quotes, ' '/" ".

The string Type the value for the radius of the circle and hit Enter: is a string which must be enclosed within a pair of double quotes, like: "Type the value for the radius of the circle and hit Enter:". After printing the string, we want the cursor to be moved to the next line. \n is an escape sequence that moves the cursor to the next line as we've seen in the table. Thus, the printf() function prints the string and then places the cursor on the next line. Semicolon terminates the statement (a function. Here, printf()).

scanf("%f", &radius);The scanf() function:

Purpose: The function scanf() reads formatted (user) input from stdin.

int scanf(const char *format, ...)Here, the format is a string that contains one or more type specifier(s) such as %d, %f, %c, %Lf etc.

... means that the string may consist of a series of specifiers (more than one fixed-length string).

By now, you already know almost everything about format/type specifiers, %d, %f, %c, %... etc.

Some common usage of the function scanf():

int/float/char/... variable = initialised_value;

scanf("%d/%f/%c/%...", &variable);One user-input:

int mangos = 0;

scanf("%d", &mangos); // scanf() to read the user input

printf("No. of mangos = %d\n", mangos);Multiple input:

int mangos = 0;

char _one_ASCII_character = 'a';

float a_fractional_no = 0.0;

int rtrnd_from_scanf_ = 0;

printf("Type the no. of mangos <space> a single ASCII char <space> a fractional no. <Enter>\n");

rtrnd_from_scanf_ = scanf("%d %c %f", &mangos, &_one_ASCII_character, &a_fractional_no);

// scanf() to read multiple input

printf("no. of mangos: %d, ASCII char: %c, fractional no: %f\n", mangos, _one_ASCII_character, a_fractional_no);

printf("No. of items read: %d\n", rtrnd_from_scanf_);Output (2nd. Multiple input):

Type the no. of mangos <space> a single ASCII char <space> a fractional no. <Enter>

7 Y 2.5

no. of mangos: 7, ASCII char: Y, fractional no: 2.500000

No. of items read: 3

Return value: On success, scanf() returns the number of items (specified by the format specifier, %d, %f, etc.) it read. int is the return type. In case of a read error, scanf() returns a number

By the way, how will you force-kill a C program? CTRL+c.

What is &?

The sign & is called the Ampersand operator. It is known as the "Address Of The Variable Operator". For more info, look here. We will learn other applications of the Ampersand operator later.

[Image from Wikipedia.]

scanf() reads user input from the stdin. scanf() needs to store the input somewhere in the memory. As a coder, it is your duty to instruct scanf() to bind that input value to a variable. It's not magic. Computers don't understand variable names. Every variable has a definite memory address (memory registers) where the program stores the value related to that variable. Variables are names. They need a room to live in. The picture above shows an image of a Pigeonhole where every pigeon lives in a designated room (hole). Imagine a name for each pigeon. Imagine an address number for each hole, too. A variable is like a pigeon that lives in a box/hole that has an address. Each memory cell/register in your PC's memory can house only one pigeon (variable) at a time.

The fun part is that every pigeon (variable) in your computer can behave like a Matryoshka doll.

With exceptions that their physical size never shrinks. One Pigeon-Shaped Matryoshka Doll can house another Pigeon-Shaped Matryoshka Doll without changing their size, thus, essentially behaving like both a pigeon and a pigeonhole simultaneously.

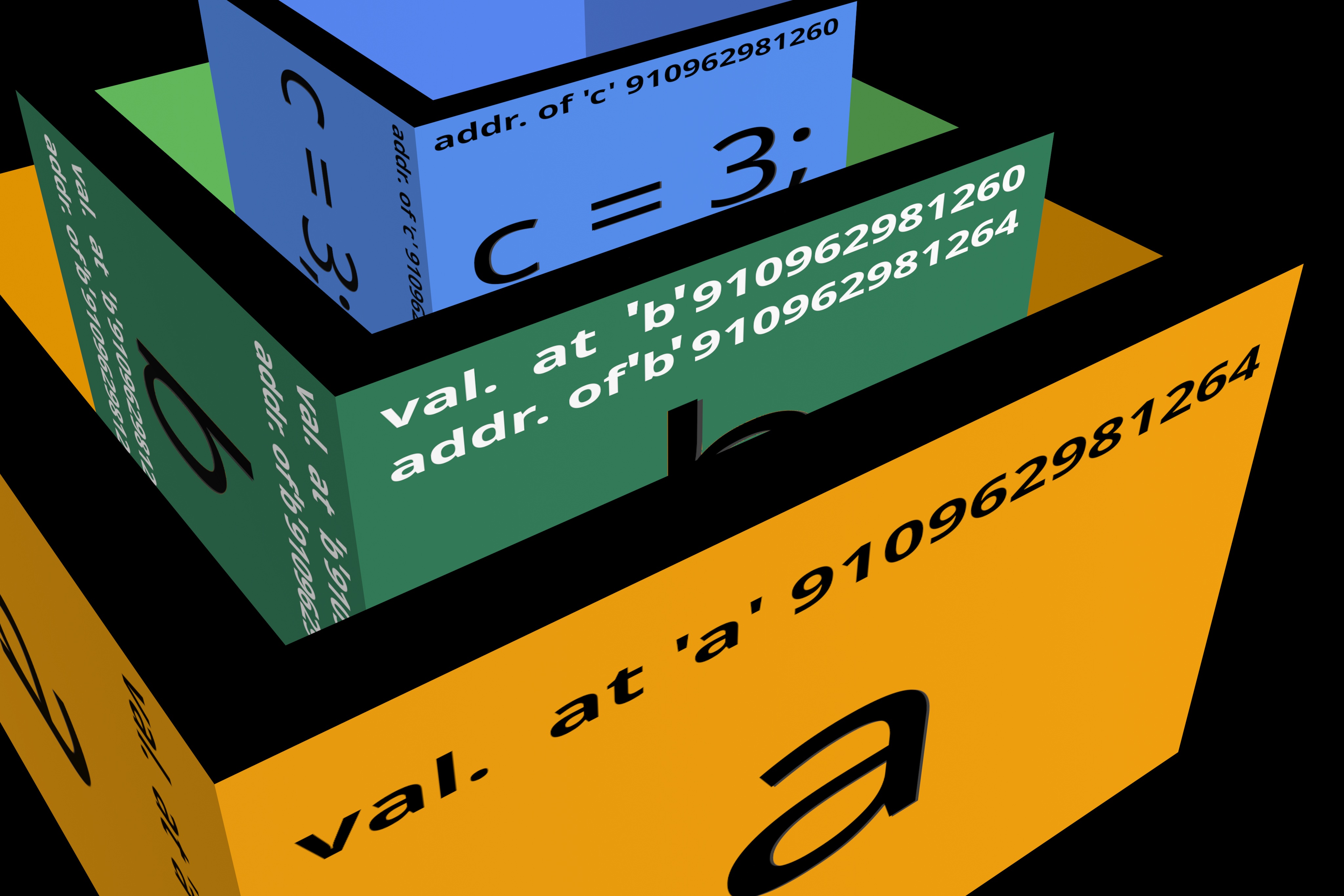

Assume there are three variables, a, b, and c. Of them, c holds a user-supplied integer value, b holds the address of c, and finally, a holds the address of b.

a points to b, b points to c.

a -> b -> c.

c has the actual value in store for them, all others are holding addresses.

Here's a rough 3D sketch (designed hurriedly) that demonstrates the fundamental principle of pointers and addresses.

Demo:

Think of variables as water and memory addresses as glasses. Pour c's water into b (glass), then b's water into another glass a.

Or imagine putting c (glass) on top of b (another glass), and b on top of a, stacking one on top of other glasses.

If you wish, you can also compare memory addresses as boxes. One exception, unlike real-life objects the size parameter doesn't change, and any of the boxes can hold other boxes. Find the glTF 3D file in 3d-models.

#include <stdio.h>

/*

Install cdecl in MSYS2:

pacman -S cdecl

Add MSYS2 bin folders to PATH

Ubuntu:

sudo apt install cdecl

Use:

cdecl.exe or cdecl

Website: https://cdecl.org/

Help:

cdecl

?

*/

int main(void) {

int **a;

/*

explain int **a;

declare a as pointer to pointer to int

Here, 'a' points to an address which will hold the address of 'b'

*/

int *b;

/*

explain int *b;

declare b as pointer to int

'b' points to an address which will hold the address of 'c'

*/

int c = 3;

/*

explain int c;

declare c as int

'c' holds an int value

Specifically,

the variable 'c'-s address stores the actual integer data

*/

b = &c; // pour the address of c into b

a = &b; // pour the address of b into a

printf("%d\n", **a);

/*

print the value stored

at the final location

(c's address)

pointed to by 'a'

*/

return 0;

}

/*

Output:

3

*/printf("addr of c %llu\n", &c);

printf("val at b %llu\n", b);

printf("addr of b %llu\n", &b);

printf("val at a %llu\n", a);addr. of c 910962981260

val. at b 910962981260

addr. of b 910962981264

val. at a 910962981264

Read from bottom to top, outer box to inner box.

We will see it when we will discuss Pointers. For now, Pigeons, Pigeonholes, and Pigeons as Matryoshka Dolls are the easiest explanation of all I could explain at best.

Coming back to the Ampersand operator, we use this to point to the variables' addresses (memory locations/registers) where the program can store the values it received from the stdin, using this & operator as the value collector. The values of the variables get stored in their respective memory locations.

int var = 0;

scanf("%d", &var);You can print the said address of the variable at any given moment of execution.

printf("%llu", &var);Here's a complete overview:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

int var = 0;

printf("Type a number & hit Enter:\n");

scanf("%d", &var);

printf("The value of the var is %d\n", var);

printf("The address of the var (HEX):\n");

printf("%p", &var);

printf("\n");

printf("The address of the var (decimal):\n");

printf("%llu", &var);

printf("\n");

return 0;

}Output:

Type a number & hit Enter:

7

The value of the var is 7

The address of the var (HEX):

0000001dd19ffcbc

The address of the var (decimal):

128070974652

We haven't left our Area of a Circle program yet.

Typecasting: It is a technique of converting one data type to another, e.g, float to double etc.

There are two kinds of typecasting: 1) Implicit and 2) Explicit.

When the compiler converts the datatype for calculating mixed types of variables, it is called Implicit Typecasting. Loss of precision may take place in the process since the compiler does so by following some pre-defined methods.

When the coder converts the type in the code, it is called Explicit Typecasting. Precision loss may occur if not done properly.

We declared our variable radius as a float, float radius = 0;. To print it as a float, we must convert its datatype.

The syntax for explicit typecasting is,

(datatype) expression

Thus,

printf("Radius = %f\n", (double)radius);pow() or double pow(double x, double y):

area = (float)(PI * (pow((double)radius, 2))); // The formula: area = pi * r^2As we've discussed before, the function pow(x,y) returns x raised to the power of y i.e. x^y (x to the power y). pow() is declared and defined in the C standard library math.h.

pow() expects doubles, not floats. All our variables are float variables. So, here we need typecasting to interfere. First we converted the radius, then the outcome of the calculation (PI * (pow((double)radius, 2))).

Multiplication operator: It is a part of the Arithmetic Operators group, denoted by *. The sign * has other applications, such as indicating a variable as a pointer. For now, we will be using it as a Multiplication Operator, one of its many applications.

PI * (pow(...)); means multiply PI by (pow(...)). a * b.

Now, We will be sending (printing) the total output to the console.

printf("Area = %f\n", (double)area);Next:

return 0;Upon successful completion, our C program will return an integer value 0 to the operating system that indicates everything went as expected, no errors (0 errors) occurred.

The C version of the program to calculate the area of a circle is complete.

The Rust version.

/*

A Rust program to calculate the area of a circle.

*/

use std::io;

fn main() {

println!("Type the value for the radius of the circle and hit Enter:");

let mut user_submitted_radius = String::new();

let mut radius: f32 = 0.0;

let mut squired: f32 = 0.0;

let mut area: f32 = 0.0;

io::stdin().read_line(&mut user_submitted_radius)

.ok()

.expect("Couldn't read user input!");

radius = user_submitted_radius.trim().parse().expect("Invalid user input!n");

squired = radius * radius;

area = 3.14 * squired; // The formula: area = pi * r^2

println!("Area = {}", area);

}Code Formatter in Rust (rustfmt):

How will you format the code for better readability?

rustfmt code.rs

Now we will see what the code does, line by line.

Notice that we didn't include a header file like stdio.h. That doesn't mean Rust doesn't have a Standard Library concept like in C. We will call the Rust's Standard Library differently.

We will have to take user input and perform calculations before printing the result as output. To do that, we need to bring the io input/output library into scope. The io library is contained in the Standard Library, known as std:.

The use keyword -> Bring symbols into scope:

use std::io;In C, we don't use a statement terminator ; after a macro, #include <stdio.h>. In Rust, we are calling a set of sub-routines io into the scope from std. It is a statement, so we are using the statement terminator. C and Rust are not exactly the same. So there will be some differences.

The double colon ::

Ref:

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/69756732/what-does-double-colon-mean-in-rust

Paths for Referring to an Item in the Module Tree - The Rust Programming Language

In the Stack Overflow thread as explained by the user "Netwave",

::behaves like a namespace accessor. You can navigate through modules or specify locations likestd::io::stdin()or call methods for objects like inString::new(). It can even be mixed, since an object may be in a module itself, so for example, the full path to the String new method would bestd::string::String::new.Refer here for more information.

In my limited understanding of Rust, it is used for accessing elements (specifically, functionalities and sub/routines) that are grouped together. Think of the serial assembly of individual links in a chain; to drag one individual link, you will have to tow preceding links.

We've already talked about The main() Function. fn is a Rust keyword prefixed before declaring a function. Move on to the next line.

println!() is a macro, which is used to send formatted strings to the console as we've discussed before. To send an unchangeable string to the console using println!(), the string must be enclosed within double-quotes, "A String". println!("A String") is the simplest example of its use.

The let keyword in Rust is used to create/declare variables.

Keywords in C and Rust are reserved words. They cannot be used for naming variables/constants/functions/structures. Each keyword has its unique purpose, and its name is reserved for that specific purpose.

An example of let:

let price = 2;We declared a new variable named price and initialised a value for it, 2.

Mutable and Immutable Variables:

In Rust, variables are immutable by default. That means once we assign a value to the variable, the value won't change.

This is not very practical since the value may be changed during the program's run, or we may have to store the output in a variable to see the result of a calculation. After all, programming is more or less performing calculations faster.

To make a variable mutable, we add the mut keyword before the variable's name:

let price = 2; // immutable

let mut dishes = 3; // mutableThe equal sign (=) tells the compiler to assign a value to a variable. It is called the Assignment Operator. We will come to the Operators later.

let mut user_submitted_radius = String::new();String is a Datatype in Rust which can be classified into two categories: 1) String Object (String) and 2) String Literal (&str).

String Literal: By default, String Literals are static texts which always point to a fixed and valid UTF-8 sequence. The compiler knows the string at the compile time since it will not change during the program's run. The more technical terminology of String Literal (&str) is "String Slices".

Some usages:

fn main() {

let ur_name:&str="Pinaki S. Gupta"; // Declaring a fixed string literal

let ur_d_o_b:&str = "1982/JUNE(06)/10"; // Declaring another fixed string literal

println!("Your Name: {}", ur_name); // Printing the fixed string

println!("Your Date of Birth: {}", ur_d_o_b);

}Your Name: Pinaki S. Gupta

Your Date of Birth: 1982/JUNE(06)/10

String Object: Sting Objects are intended to be changed during the program's run. The Rust Standard Library provides the string input/output feature, defined in the standard library as a public structure, pub struct String. It (the String object) is "growable", mutable, UTF-8 encoded, heap-allocated, and not null-terminated. It is used when the string value can be changed at the run time.

BTW, how to create a String Object?

String::new()The following syntax creates an empty string.

String::from()fn main() {

let blankstr = String::new();

println!("The empty str is: {}", blankstr);

let str01 = String::from("Rust is good!");

println!("str01 is: {}", str01);

}The empty str is:

str01 is: Rust is good!

String Object calling Methods/Functions (More details).

Method/fn |

Signature | Description |

|---|---|---|

new() |

pub const fn new() -> String |

Creates a new empty String. |

to_string() |

fn to_string(&self) -> String |

Converts the given value to a String. |

replace() |

pub fn replace<'a, P>(&'a self, from: P, to: &str) -> String |

Replaces all matches of a pattern with another string. |

as_str() |

pub fn as_str(&self) -> &str |

Extracts a string slice containing the entire string. |

push() |

pub fn push(&mut self, ch: char) |

Appends the given char to the end of a given String. |

push_str() |

pub fn push_str(&mut self, string: &str) |

Appends a given string slice onto the end of a given String. |

len() |

pub fn len(&self) -> usize |

Returns the length of a given String, in bytes. |

trim() |

pub fn trim(&self) -> &str |

Returns a string slice with leading and trailing whitespace removed. |

split_whitespa ce() |

pub fn split_whitespace(&self) -> SplitWhitespace |

Splits a string slice by whitespace and returns an iterator. |

split() |

pub fn split<'a, P>(&'a self, pat: P) -> Split<'a, P> , where P is pattern can be &str, char, or a closure that determines the split. |

Returns an iterator over substrings of this string slice, separated by characters matched by a pattern. |

chars() |

pub fn chars(&self) -> Chars |

Returns an iterator over the chars of a string slice. |

Examples of the Methods mentioned above:

new(): new() is used to create an empty string. Here, we create an empty string using new() and appending the string Hi, Rust! at the end of the empty string, thus, essentially initialising the variable.

fn main() {

let mut variab = String::new();

variab.push_str("Hi, Rust!");

println!("{}", variab);

}Hi, Rust!

to_string(): We convert a given variable value to a string using to_string(). The text surrounded with double-quote "" will be converted to a string object.

fn main() {

let a_string = "This is an example of to_string()".to_string();

println!("{}", a_string);

}This is an example of to_string()

replace(): Finds a pattern and replaces all matches with a supplied value. It is a function that takes two parameters, 1) A string pattern to search for, and 2) The new value which will replace all matches found. In our example, the pattern Rust will be searched for and replaced with Crust wherever found.

fn main() {

let some_str = "Rust isn't rusty!";

let another_str = some_str.replace("Rust", "Crust");

println!("{}", another_str);

}Crust isn't rusty!

as_str(): as_str() extracts a string slice containing the entire string. We are finding and extracting the string slice C which is contained in the variable a_word_str.

fn main() {

let a_word_str = String::from("C");

let a_word_str_as_string = a_word_str.as_str();

println!("Example of as_str() {}", a_word_str_as_string);

}Example of as_str() C

push(): The push() function appends a supplied char (here, s) to the end of a String specified (Apple).

fn main() {

let mut fruit = "Apple".to_string();

fruit.push('s');

println!("{}", fruit);

}Apples

push_str(): The push_str() function/method appends a given string slice (here, is my self-help guide, not a tutorial.) onto the end of a given String (here, Crust ). Here, the string to push is is my self-help guide, not a tutorial..

fn main() {

let mut paper = String::from("Crust ");

paper.push_str("is my self-help guide, not a tutorial.");

println!("{}", paper);

}Crust is my self-help guide, not a tutorial.

len(): Returns the total number of characters in a String (the length) in bytes (including spaces). We know that each character takes one byte in computer memory. So, the number of bytes returned is the number of characters found in a String.

fn main() {

let str01 = "C & Rust both are easy."; // 23 char -> C & Rust both are easy.

println!("Length: {}", str01.len());

}Length: 23

trim(): The function trim() removes leading and trailing whitespace characters. NOTE: This function will not remove the inline spaces (whitespace characters found inside the string text). Only the whitespace chars found in the beginning and end will be trimmed.

fn main() {

let mut a_str_with_blank_spaces =

" Every programmer is an author. - Sercan Leylek \n";

println!("{}", a_str_with_blank_spaces);

println!("Length Before trim(): {}", a_str_with_blank_spaces.len());

println!(

"Length After trim(): {}",

a_str_with_blank_spaces.trim().len()

);

a_str_with_blank_spaces = a_str_with_blank_spaces.trim();

println!("{}", a_str_with_blank_spaces);

} Every programmer is an author. - Sercan Leylek

Length Before trim(): 59

Length After trim(): 46

Every programmer is an author. - Sercan Leylek

split_whitespace(): The function split_whitespace() splits the whole input string into different words whenever a whitespace character is detected. The function also returns an iterator. We used the variable token as the iterator to count the number of times the function detected a whitespace char.

Don't look at the for loop. We will learn Loops at the right moment.

fn main() {

let a_phrase = "Cato Dogo love Omelette Fish".to_string();

let mut i = 1;

for token in a_phrase.split_whitespace() {

println!("Word {}: {}", i, token);

i += 1;

}

}Word 1: Cato

Word 2: Dogo

Word 3: love

Word 4: Omelette

Word 5: Fish

split(): split() finds a user-supplied pattern (here, ,), then splits the String every time it detects a match. It also returns an iterator for counting. Note that the result cannot be stored for later use. There are workarounds such as collect(), but it is beyond the scope of our skeleton anatomy. The workaround collect() will be covered later.

fn main() {

let items = "Mango,Banana,Guava,Pineapple";

for token in items.split(",") {

println!("Item: {}", token);

}

}Item: Mango

Item: Banana

Item: Guava

Item: Pineapple

chars(): Returns an iterator over the chars of a string slice. That means each time the function char() detects a character, it returns an iterator. So, we can count the number of chars in a Sting Slice and access individual characters. Although, we are not counting chars here.

fn main() {

let string01 = "Crust".to_string();

for i in string01.chars() {

println!("{}", i);

}

}C

r

u

s

t

String Concatenation using the + Operator and references (&):

Appending a string to another string is termed String Concatenation or Interpolation. The result of this operation is a new string object. The + operator internally calls the function add(). The add() function takes two parameters, 1) self – The string object itself, and 2) The second parameter is a reference to the second string object (similar to the address of method in C).

// The add() function

add(self,&str) -> String {

// Returns a String object

}We will be using syntax like let s4 = s1 + &s2 + &s3; without looking at the internal mechanism.

fn main() {

let s1 = "C ".to_string();

let s2 = "and ".to_string();

let s3 = "Rust.".to_string();

let s4 = s1 + &s2 + &s3; // s2, s3 references are passed

println!("{}", s4);

}C and Rust.

The format!() Macro: It can also be used to concatenate strings.

fn main() {

let s1 = "C".to_string();

let s2 = "and".to_string();

let s3 = "Rust.".to_string();

let s4 = format!("{} {} {}", s1, s2, s3);

println!("{}", s4);

}C and Rust.

Type Casting: Converting a number to a string and vice versa.

Integer to String:

fn main() {

let n = 714285;

let n_2_str = n.to_string();

// Num to str conversion

println!("The str is: {}", n_2_str);

println!("Operation successful: {}", n_2_str == "714285");

}The str is: 714285

Operation successful: true

Integer to String and String to Integer (combined):

fn main() {

let n = 714285;

let n_2_str = n.to_string(); // Num to str conversion

let str_2_num = n_2_str.parse::<i32>().unwrap(); // Str to num conversion

// The parse() method can be used for converting strings to integers

// Procedure:

// let a_string = "25".to_string(); // `parse()` works with `&str` and `String`

// let an_int_val = a_string.parse::<i32>().unwrap();

// Num to str conversion

println!("Num to string: {}", n_2_str);

println!("Success: {}", n_2_str == "714285");

// Str to num conversion

println!("String to num: {}", str_2_num);

println!("Success: {}", str_2_num == 714285);

}Num to string: 714285

Success: true

String to num: 714285

Success: true

By now, we know the purpose of the following line in our Area of a Circle program.

let mut user_submitted_radius = String::new();Now we will decipher the next line:

let mut radius: f32 = 0.0;let is a keyword used to declare variables. The list of keywords in Rust can be found here, as we've discussed before.

We've also talked about mutable and immutable variables. By default, Rust variables are immutable, which means once you've assigned a value to a variable, it cannot be changed. To overcome this limitation, you'll have to declare/create variables as mutable variables. To make a variable Mutable, the mut keyword is used. Values of mutable variables can be altered during the execution of the program.

We will discuss Variables and Data Types before trying to understand the purpose of the line let mut radius: f32 = 0.0;.

Variables:

A variable is a named storage class which is used in C and Rust programming for storing numeric values or texts in the computer memory. Depending on the type of value a variable stores, a variable is closely associated with a particular Data Type. We've covered data types in C before. The data type determines two factors primarily: 1) The type of value (data) a variable stores (integer, character, fractional numbers etc.), and 2) The size (in bit) it will occupy in the computer memory.

Variable Naming Convention: Variable naming in Rust is quite similar to that of in C. We've covered variable naming in C. I'll repeat what we discussed, keeping things short.

Start with a small letter or an underscore (_). After writing the first character of the variable, you can use numbers. There's an exception, unlike in C, you cannot use Capital Letters anywhere in Rust variable naming. So, don't use Capital Letters anywhere while giving a variable a name. Never use special characters or whitespace characters.

Legal:

variable, _variable, variable01, variable_01, variable_one, string_variable_two

Illegal:

Variable, 01variable, v@r!able, variable 01, variableOne, stringVariableTwo

The syntax for creating (declaring) a variable:

let variable_name = value; // DataType not specified

let variable_name:data_type = value; // DataType specifiedRust doesn't strictly enforce type declaration while creating a variable. The compiler infers the data type from the value assigned to the variable. However, you should specify the type for accessing the variables later with relative ease. Also, some errors can be avoided, and the compiler will produce better-optimised compiled code if you specify the type beforehand. The following are some examples of declaring fractional (float) numbers. Note that Rust is a statically typed language, which means that it

must know the types of all variables at compile time. Either the compiler will do that, or the onus of doing so is left upon the person who writes the program.

let temperature: f64 = 27.092;let mut radius: f32 = 0.0;Primarily, Rust has two Data Types, 1) Scalar, and, 2) Compound. (Citation needed.)

Scalar Data Types:

-

Integers

-

Floating-point numbers

-

Booleans

-

Characters

Rust has two primary Compound Data Types:

-

Tuples

-

Arrays

Integer Types in Rust:

| Length | Signed (+/-) | Unsigned (+) | How to declare |

|---|---|---|---|

8-bit |

i8 |

u8 |

let mut int_var: i8 = 0; or, let mut uint_var: u8 = 0; |

16-bit |

i16 |

u16 |

let mut int_var: i16 = 0; or, let mut uint_var: u16 = 0; |

32-bit |

i32 |

u32 |

let mut int_var: i32 = 0; or, let mut uint_var: u32 = 0; |

64-bit |

i64 |

u64 |

let mut int_var: i64 = 0; or, let mut uint_var: u64 = 0; |

128-bit |

i128 |

u128 |

let mut int_var: i128 = 0; or, let mut uint_var: u128 = 0; |

| arch (architecture, 64/32/16/8-bit) | isize |

usize |

The isize and usize types depend on the architecture of the

computer the Rust program is running on. The datatypes isize and usize are primarily used for indexing some sort of collection.

What about the range? According to Rust's official documentation,

Each signed variant can store numbers from

$-\left( 2^{\left (n-1\right)} \right)$ to$+\left( \left( 2^{\left (n-1\right)} \right) -1 \right)$ inclusive, where$n$ is the number of bits that variant uses. So ani8can store numbers from$-2^{8-1} = -2^{7} = -128$ to$2^{8-1} - 1 = 2^{7} - 1 = 128 - 1 = 127$ , which equals-128to127. Unsigned variants can store numbers from$0$ to$\left( 2^{n} - 1 \right)$ so au8can store numbers from$0$ to$\left( 2^{8} - 1 \right)$ , which equals$0$ to$\left( 2^{8} - 1 \right) = 256 - 1 = 255$ .

Data Types and Ranges in Rust calculated using the same techniques we discovered when we calculated the range of each data types in C. Ultimately, the range of a data type begs one question, "how many bits a data type allows"? It doesn't matter whether you are calculating the range in C or Rust.

Number Separator: In Rust, you are allowed to use an underscore character (_) as a separator while assigning numeric values to variables for better readability, such as 98_222, which means 98222. 5_000 equals 5000 in Rust. Thus, let mut var: i32 = 5_000; is essentially the same as let mut var: i32 = 5000;.

Literals:

fn main() {

// Suffixed literals, their types are known at initialization

let value = -257i64; // i64 (Length: 64 bit, signed.)

/*

Unsuffixed literals, their types are determined by

the Rust compiler depending on how they are used

*/

// let i = 13;

// let f = 1.6;

let x = value.abs(); // The function abs() returns the absolute value

println!("value is {}", value);

println!("The absolute value of x is {}", x);

// `size_of_val` returns the size of a variable in bytes (1 byte = 8 bits)

println!("size of `x` in bytes: {}", std::mem::size_of_val(&x));

println!("size of `x` in bits: {}", (8 * std::mem::size_of_val(&x)));

}Here's a brief explanation from the Rust documentation:

std::mem::size_of_valis a function, but called with its full path. Code can be split in logical units called modules. In this case, thesize_of_valfunction is defined in thememmodule, and thememmodule is defined in thestdcrate.

Modules and Crates will be discussed later.

value is -257

The absolute value of x is 257

size of `x` in bytes: 8

size of `x` in bits: 64

Numeric literals (e.g., -52) can be type-annotated (e.g., i32) by adding the type (i32) as a suffix (-52i32). For example, to specify that the literal (integer number) 43 should have the type i64, write 43i64. For mutable variables, specify the type as let mut temperature: f64 = 0.0;. For the immutable (fixed) ones, there's also the option to specify the type as let temperature: f64 = 27.092;, as well as let temperature = 27.092f64;. What if you initialise a variable like let mut value = 0i64;? No problem. But, you'll have to use the old assigned value 0 before assigning a new value to the variable value.

fn main() {

let mut value = 0i64;

value = -257;

println!("value is {}", value);

}Compiler warning:

warning: value assigned to `value` is never read

--> testrst.rs:2:13

|

2 | let mut value = 0i64;

| ^^^^^

|

= note: `#[warn(unused_assignments)]` on by default

= help: maybe it is overwritten before being read?

warning: 1 warning emitted

value is -257

However, the following code will compile as usual.

fn main() {

let mut value = 0i64;

println!("value is {}", value);

value = -257;

println!("value is {}", value);

}value is -257

The type of "unsuffixed" numeric literals will depend on how they are used. If no constraint exists, the compiler will use i32 for integers, and f64 for floating-point numbers.

Integer/Number Literals:

| Integer/Number Literals | Can be expressed as: |

|---|---|

| Decimal | 90_000 |

| Hexadecimal | 0xff |

| Octal | 0o77 |

| Binary | 0b1111_0000 |

Byte (u8 only) |

b'A' |

Floating-Point Types in Rust:

Floating-point numbers are represented according to the IEEE-754 standard. The f32 type is a single-precision float, and f64 has double precision. The default type is f64.

| Length | Always Signed (+/-) |

|---|---|

32-bit |

f32 |

64-bit |

f64 |

If unspecified, all fractional (float) numbers default to f64.

Basic Mathematical Operations:

-

Addition

-

Subtraction

-

Multiplication

-

Division

-

Remainder

Integer division rounds down to the nearest integer.

fn main() {

// addition // sum

let operation_addition = 15 + 3;

println!("operation_addition: {}", operation_addition);

// subtraction // difference

let operation_subtraction = 36.5 - 2.3;

println!("operation_subtraction: {}", operation_subtraction);

// multiplication // product

let operation_multiplication = 6 * 50;

println!("operation_multiplication: {}", operation_multiplication);

// division

let quotient = 87.4 / 49.3;

println!("quotient: {}", quotient);

let floored = 6 / 10; // Results in 0

println!("floored: {}", floored);

// remainder

let remainder = 27 % 5;

println!("remainder: {}", remainder);

}

/*

operation_addition: 18

operation_subtraction: 34.2

operation_multiplication: 300

quotient: 1.772819472616633

floored: 0

remainder: 2

*/The Boolean Type:

The Boolean type in Rust has two possible values, either true or false. Booleans occupy one byte in size. A Boolean is expressed by the keyword bool.

fn main() {

let yeah = true;

println!("yeah: {}", yeah);

let nope: bool = false; // with explicit type annotation

println!("nope: {}", nope);

}

/*

yeah: true

nope: false

*/Boolean values are primarily used in Flow Control (which will be covered later) e.g., if, else, else if, loop, while, for to break or take another direction after meeting certain given conditions.

The Character DataType: The keyword char is used to deal with Character Data Types.

fn main() {

let c = 'z';

println!("c: {}", c);

let z: char = 'ℤ'; // with explicit type annotation

println!("z: {}", z);

let thumbs_up = '👍';

println!("thumbs_up: {}", thumbs_up);

}

/*

c: z

z: ℤ

thumbs_up: 👍

*/char literals are specified with single quotes let c = 'z';, as opposed to string

literals let name = "Pinaki";, which are specified with double quotes. Rust’s char type is four bytes in size and represents a Unicode Scalar Value, which means it can represent a lot more than conventional ASCII characters. Unicode Scalar Values range from U+0000 to U+D7FF and U+E000 to U+10FFFF. See: Storing UTF-8 Encoded Text with Strings - The Rust Programming Language.

Compound DataTypes: Compound types can group multiple values into one type.

There are two kinds of Compound DataTypes in Rust,

-

Tuple

-

Array

The Tuple Type: Tuple is used to store values of multiple data types into one type, grouping them all together. It is created by writing a comma-separated list of values inside parentheses. Each position in the tuple has a type.

Demo: In the following program, we first create a tuple (a variable. Here, tup) of values (237, 9.325, 7). We also specify the data types as (i32, f64, u8). Then we group three variables x, y, and z using the keyword let, and treat the group as the variable tup itself, let (x, y, z) = tup. Each variable inside the tuple-variable tup is separated internally as x, y, and z. The process is known as destructuring. It breaks the single tuple into three (equal to the number of values grouped together: 3) parts.

fn main() {

let tup: (i32, f64, u8) = (237, 9.325, 7);

let (x, y, z) = tup;

println!("The value of z is: {z}");

println!("The value of x is: {x}");

println!("The value of y is: {y}");

}

/*

The value of z is: 7

The value of x is: 237

The value of y is: 9.325

*/We can also access a single element of a tuple directly by putting a dot/full stop (.) after writing the index of the value we want to access. Note that the index starts from ZERO (0), not ONE (1). The first index in a tuple is 0. Both in C and Rust, the counting of array elements starts from ZERO (0). We will come to it in the chapter Array.

fn main() {

let tup: (i32, f64, u8) = (237, 9.325, 7);

let element_one = tup.0;

let element_two = tup.1;

let element_three = tup.2;

println!("element_one is: {element_one}");

println!("or, element_one is: {}", element_one);

println!("or, element_one is: {}", tup.0);

println!();

//