- One of the earliest and simplest ciphers

- Used by (you guessed it) Caesar himself, who is claimed to have used a shift of 3

| a | b | c | d | e | f | ... | u | v | w | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | e | f | g | h | i | ... | x | y | z | a | b | c |

- We don't want to actually deal with letters, words, etc. Modern cryptography deals almost solely with numbers. We use an encoding function to transform letters (or words) into numbers, and vice versa.

- We also need a secret key (sometimes just key) to perform our encryption and decryption.

- The keyspace is the set of possible keys. Usually we want the keyspace to be prohibitively large -- this way, using brute force to find the key is no longer feasible.

- What should be our encoding scheme?

- What should our encryption and decryption functions look like?

- What does our keyspace look like?

- Encoding scheme: a↦0, b↦1 seem reasonable

- Encryption function: f(x,k)=x+k (mod 26)

- Decryption function: f-1(x,k)=x-k (mod 26)

- Keyspace: technically infinite, but really only 26 possibilities

- In a mod N arithmetic system, one counts [0, N). Upon reaching N, the system wraps around and begins counting at 0 again.

- Clocks are modular arithmetic systems, hence modular arithmetic is sometimes called clock arithmetic.

- The 24-hour clock counts 0..23, and then starts back over at 0 again.

- Clocks are modular arithmetic systems, hence modular arithmetic is sometimes called clock arithmetic.

- Notation:

- Computer Science: x mod N is a function that spits out the remainder of x/N

- Mathematics (and this workshop): x ≡ a mod N ― x is congruent to a mod N, that is to say that the remainder of x/N is a, so x maps to a in the mod N system.

- 3 ≡ 3 mod 5

- 10 ≡ 0 mod 5

- 25 ≡ 4 mod 7

- -1 ≡ 6 mod 7

- Let's work through some examples:

- Encrypt

CRYPTOWORKSHOPusing a key of 3 - Decrypt

WLSJNI CM WIIFusing a key of 20 (or a key of -6)

- Notice that if the key is 13, we don't actually need a decryption function -- it would be the same as the encryption function

- Has a special name: ROT13

- f(x, 13) = x + 13 ≡ (x + 13) mod 26

- f(x+13, 13) = x + 26 ≡ x mod 26

- (Supposedly) used in forums to hide spoilers

- Who thinks the Caesar cipher is secure?

- The keyspace is too small, so brute force attacks are almost trivial

- Notice that each letter is mapped to exactly one other letter (and always that letter)

- i.e.,

BANANAwith a key of 11 isMLYLYL- Notice

A->Levery time

- Notice

- So there's another inherent weakness in the Caesar cipher

- It reflects the natural frequency of letters in a language

- e is the most common letter in the English alphabet

- Can we make the Caesar cipher more secure?

- We can use the Vigenère cipher, which uses words as keys. For instance, encrypting

CRYPTOGRAPHYwith the key ofKEYgives us...

- We can use the Vigenère cipher, which uses words as keys. For instance, encrypting

| C | R | Y | P | T | O | G | R | A | P | H | Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | E | Y | K | E | Y | K | E | Y | K | E | Y |

| M | V | W | Z | X | M | Q | V | Y | Z | L | W |

- It's worth noting that Vigenère is pretty easy to crack too, given a sufficiently large cipher.

-

Invented at the end of WWI

-

But mainly you see it talked about in context with WWII

-

Multiple Variations

- Has a total of 150,738,274,937,250 (151 trillion) different ways pairs of letters could be interchanged

- The Polish and British cryptographers and mathematicians spearheaded the attack on the Enigma Machine

- (Extremely) short video showing an Enigma Machine in action: [Working Enigma]{https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5SBNc-lpJXU}

- Courtesy of Wikipedia

- Paper enigma: http://dave-reed.com/DIYenigma/

- Notice that a letter can't encode to itself

- Notice that if a letter X maps to Y, then Y also maps to X

- Poor security or thought in how the Enigma was used

- Cribs are common phrases that you might see expect to see in the plaintext

- For example, you might expect the first word of a letter to be "Hello"

- Or, every message ended in "Heil Hitler"

- Common rotor settings such as "AAA" or "BBB"

- Retransmitting a message (or a nearly identital message) using a different cipher (or different key)

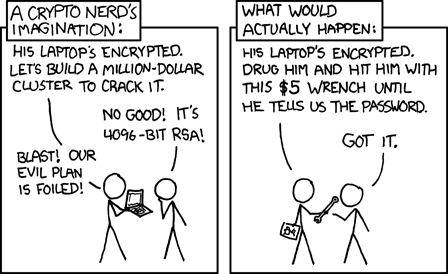

Real-World Crypto (courtesy of xkcd)

- Notice that both the Caesar Cipher and the Enigma machine rely on an assumption

- They both assume that the parties have communicated some secret

- First published by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman in 1976

- But actually conveived before then by researchers at GCHQ, Great Britain's secret intelligence agency

- Allows parties to decide on a secret key even in the presence of evesdroppers.

- Not actually an encryption scheme, but a key generation scheme to be used in conjunction with some other form of encryption.

- Let's go back to the idea of modular arithmetic

- Choose a prime p and a number g It turns out that we can compute ga mod p quickly even for very large a's.

Let p = 67, g = 7, a = 28. We need to find g28 mod 67. Because g28 = g16 · g8 · g4, we can find what g28 is congruent to in mod 67 using repeated squaring:

- g2 = g · g = 7 · 7 = 49 ≡ 49 mod 67

- g4 = g2 · g2 = 49 · 49 = 2401 ≡ 56 mod 67

- g8 = g4 · g4 = 56 · 56 = 3136 ≡ 54 mod 67

- g16 = g8 · g8 = 54 · 54 = 2916 ≡ 35 mod 67

Since 28 = 16 + 8 + 4, we see

- g28 = g16 · g8 · g4 = 35 · 54 · 56 = 105840 ≡ 47 mod 67

Notice that this algorithm only takes log2(n) squarings. So even very large a's will perform relatively quickly.

So what do we do with this information?

- Let us suppose we have 3 parties.

- Alice, who wants to talk to Bob without being overheard

- Bob, who wants to talk to Alice without being overheard

- Eve, who wants to eavesdrop on Alice and Bob's conversation

- Furthermore, Alice and Bob have no prior information about each other

- That is, they haven't decided on a secret key yet How are Alice and Bob going to decide on a secret key?

Step 1:

- Alice and Bob (openly) communicate a prime p and a number g

Step 2:

- Alice chooses a secret number a, calculates ga mod p, and sends that information to Bob

- Bob chooses a secret number b, calculates gb mod p, and sends that information to Alice

Step 3:

- Alice calculates (gb mod p)a mod p = gab mod p

- Bob calculates (ga mod p)b mod p = gab mod p

The secret key is gab mod p

| Alice | Eve | Bob | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decide on g, p | g, p | g, p | g, p |

| Secretly choose a number (c) | a | b | |

| Calculate gc mod p | ga mod p | gb mod p | |

| Send gc to the other party | gb mod p | ga mod p, gb mod p | ga mod p |

| Feel secure in your secrecy ;) | (gb)a mod p | ??? | (ga)b mod p |

p = 67, g = 7

| Alice | Eve | Bob | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decide on g, p | g = 7, p = 67 | g = 7, p = 67 | g = 7, p = 67 |

| Secretly choose a number (c) | a = 28 | b = 15 | |

| Calculate gc mod p | 728 mod 67 = 47 | 715 mod 67 = 5 | |

| Send gc to the other party | gb mod p = 5 | ga mod p = 47, gb mod p = 5 | ga mod p = 47 |

| Calculate gab mod p | (gb)a mod p = 4728 mod 67 = 14 | ??? | (ga)b mod p = 475 mod 67 = 14 |

Notice that if Eve finds either a or b, she knows the secret key.

- The problem of finding a from ga mod p is known as the Discrete Log Problem. As far as we know, this is a hard problem.

-

While we've chosen to focus on Diffie-Hellman for our discussions on Public Key Cryptography, there are other methods by which PKC can be accomplished. One of the most famous and widely used encryption schemes, RSA, relies on prime factorization being a hard problem to solve efficiently.

-

Our best solutions at the time are the General Number Field Sieve (faster for integers greater than 10100) and the Quadratic Sieve (faster for integers less than 10100)

- It's worth keeping in mind that RSA can use up to 4,096-bit keys, resulting in keys greater than 101000

-

-

Even with optimizations such as the General Number Field Sieve, with our current, classical computing power, it could take the lifetime of the universe to crack problems of prime factorization or the Discrete Log Problem

-

Quantum computing gives us access to new algorithms that drastically reduce the time needed to solve problems of prime factorization or discrete logs by exploiting features of quantum mechanics such as superposition and entanglement.

- Crucial to understanding quantum computing is the understanding that quantum states can be added together like waves to get new, equally valid quantum states.

-

It's a common misconception that quantum computers solve problems by checking every possibility in parallel. However, this is no different than multiprogramming techniques like wiring together a bunch of classical computers...

-

Quantum computing algorithms like Shor's algorithm take advantage of quantum states' wavelike behavior and constructive/destructive interference to amplify solutions that are probabilitistically more correct.

- In technical, computational mumbo-jumbo, this means problems that have NP (nonpolynomial) runtime in classical computing now have P (polynomial) runtime in quantum computing. This is called Bounded-Error Quantum Polynomial runtime.

We don't have nearly enough time to go into these algorithms, but here's an incredibly helpful playlist to learn more.

-

Just as quantum computing destroys modern cryptography, it also provides solutions...

-

... The most prominent being Quantum Key Distribution.

-

Like Diffie-Hellman, QKD isn't itself an encryption scheme, but rather a secure means of key exchange to be used in conjunction with other encryption schemes like AES.

-

Thanks to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the no-cloning theorem, it's impossible for an eavesdropper to observe the key exchange without modifying the quantum information. If an eavesdropper tries, the information is modified, and the key exchange therefore fails, alerting the two communicating parties to the eavesdropper's presence.

-

-

There also seem to be problems like lattice-based encryption that seem to resist even quantum solutions. See §1.3

- Thanks to Dr. Fili of the OSU Mathematics department for providing input and references for content