The pancreas computed tomography (CT) dataset consists of 18,942 DICOM images of 80 patients, with a total size of 9.3GB, and their corresponding manually annotated masks as the ground-truths.

Automatic image (2D) and volume (3D) semantic segmentation of pancreas computed tomography (CT).

F2 score and dice similarity coefficient (DSC).

For each patient, there are several medical images where each image is a single slice of the scan with a resolution of 512×512 pixels. Among patients, the number of slices varies from 181 to 466 with a median of 237. The annotation masks label anomalies and are in Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative (NIfTI) format. Regions in the CT scan slices with pixel values of 1 and 0 denote areas with and without anomalies, respectively. With this dataset, I perform both 2D and 3D medical image segmentation. In 2D, I consider each slice on its own, and in 3D, I consider the volume built on the collection of slices of each patient.

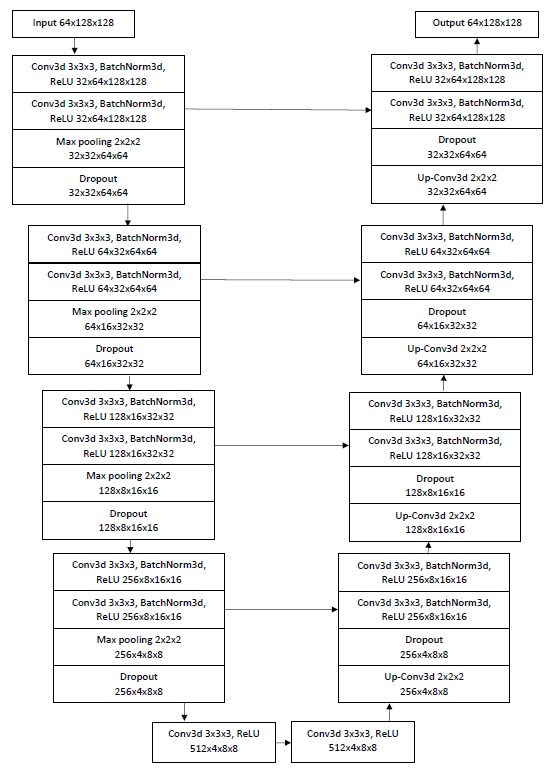

I use 2D-UNet and 3D-Unet which are fully convolutional networks developed for biomedical image segmentation. The 2D UNet architecture contains an encoder and a decoder path each with four resolution steps. The encoder path captures the context of the image and the decoder path enables localization. Each of the encoder and decoder paths consists of 4 blocks which contain two 3×3 convolutions each followed by a batch normalization for faster convergence and a rectified linear unit (ReLU), and then a 2×2 max pooling with strides of two in each dimension. In the decoder path, each layer consists of an upconvolution of 2×2 by strides of two in each dimension, followed by two 3×3 convolutions each followed by a ReLU. Through shortcut connections from layers of equal resolution in the encoder path, the essential high-resolution features are provided to the decoder path. To avoid bottlenecks, the number of feature channels is doubled after each maxpooling and halved in each upconvolution. To avoid overfitting, I use dropout with a ratio of 20% after each maxpooling and upconvolution. In the last layer, a 1×1 convolution reduces the number of output channels to 1. Then, I apply a sigmoid along with each pixel to form the loss. I have initialized the weights using Gaussian distribution with a standard deviation of √(2 ⁄ N), where N is the number of incoming nodes of one neuron. 3D UNet architecture is an extension of 2D UNet, where all 2D operations are replaced by their 3D counterparts: 3D convolutions, 3D maxpooling and 3D up-convolutional layers. Figure 1 shows a sample of the 3D UNet with 32 input features for a patch of 64×128×128 voxels.

Figure 1. 3D UNet architecture

In medical image segmentation, the number of anomaly voxels is usually more than that of voxels without anomalies. The segmentation prediction of such an unbalanced dataset is biased toward high precision but low sensitivity (recall), which is undesirable in computer-aided diagnosis and clinical decision support systems. To achieve a better trade-off between precision and sensitivity, Salehi et al. have proposed a loss function based on the Tversky index, which is a generalization of the DSC and the F_β scores. I use the Tversky loss function.

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the network, I calculate and report specificity, sensitivity, precision, F1 score, F2 score and DSC.

I randomly assign patients to train, validation and test sets using a 70/10/20 split, resulting in a set of (56, 7, 17) pairs of images and masks. The train data is shuffled before getting batched. Three-dimensional medical images have repetitive structures with slight variations. Hence, I resize each patients’ image and mask to 128×256×256 voxels, where the first dimension indicates the total number of slices in the volume and the next two dimensions represent the size of a 2D slice (depth, height, width). For the 2D study, I use these resized slices as data. For the 3D study, due to GPU memory constraints, it is not feasible to use the entire volume of each patient in a single batch. Hence, I split each patient’s image and mask into smaller volumes (subvolumes) which are called patches in computer vision. Patch size is a hyperparameter in this study. I use data augmentation on the training data to avoid overfitting. For the 2D study, I use the PyTorch augmentation library albumentations. I implement Rotate, VerticalFlip, PadIfNeeded and GridDistortion. As for the 3D study, I use 3D RandomAffine (scales, degrees), RandomElasticDeformation, and RandomFlip (vertical flip) transforms from the TorchIO package.

I did experimentation on the effect of types of the activation function. the number of feature channels and patch sizes on the performance metrics. I compared the metrics when ReLU is substituted by the Swish activation function.

The network output and the ground truth labels are compared using sigmoid nonlinearities with the Tversky loss. Voxels with probabilities of 0.5 or higher are considered with anomalies and the rest of the voxels are considered without anomalies. I train all models with α=0.3 and β=0.7. The best model is saved based on an increase in DSC. I employ an Adam optimizer. For the training schedule, I use Leslie Smith’s one-cycle learning rate Policy with 100 epochs. In the one-cycle learning policy, the learning rate varies from a lower value to a maximum rate and then reduces to the lower value, all in 2 steps of equal size. The maximum learning rate is tuned for each model and the lower rate is approximately 1/10 of the maximum rate.

The highest mean DSC that I got is 70.32±10.87% with the following parameters: patch size of 32×64×64, batch size of 16, 32 in_features, and ReLU activation function.

| specificity | sensitivity | precision | F1_score | F2_score | DSC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 17.000000 | 17.000000 | 17.000000 | 17.000000 | 17.000000 | 17.000000 |

| mean | 0.999726 | 0.165663 | 0.291462 | 0.776711 | 0.677990 | 0.703180 |

| std | 0.000134 | 0.074426 | 0.093333 | 0.092947 | 0.110595 | 0.108743 |

| min | 0.999426 | 0.049721 | 0.150370 | 0.578306 | 0.465728 | 0.510072 |

| 25% | 0.999658 | 0.103727 | 0.205767 | 0.731116 | 0.583766 | 0.608891 |

| 50% | 0.999741 | 0.187936 | 0.315979 | 0.762804 | 0.701684 | 0.703203 |

| 75% | 0.999845 | 0.212360 | 0.376995 | 0.841608 | 0.742929 | 0.762804 |

| max | 0.999896 | 0.274778 | 0.404222 | 0.931877 | 0.920033 | 0.931877 |

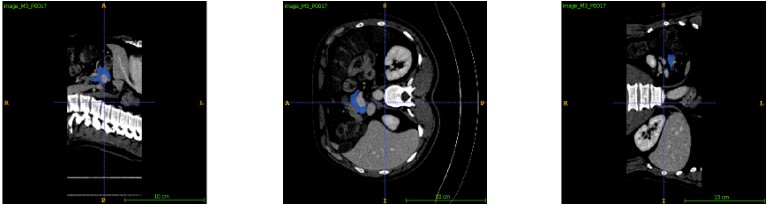

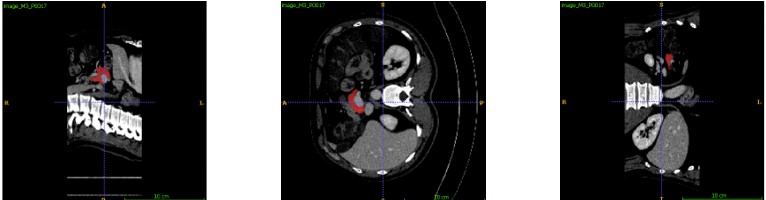

Figure 2 shows three views of an example of pancreas segmentation plotted by ITK-SNAP. The top row images are the manual ground truth annotations and the bottom row ones are the automatic segmentations.

Figure 2. Manual annotation (top) and automatic segmentation (bottom)

- Download the dataset to your Google Drive.

- You may change the patch parameters, batch size, optimizer type, threshold probability limit, and the number of epochs in the “Set the hyperparameters” section.

- If you wish to find the maximum learning rate, set lr_find to true and run the code up to the “Train and validate the model” section. Change the scheduler “max_lr” value to the suggested rate and set the “lr” in the optimizer definition to 1/10 of the “max_lr”. Set “lr_find” to False and rerun the code.

- The notebook generates a CSV file for the history of train and validation loss, specificity, sensitivity, precision, F1_score, F2_score, and DSC.

- The notebook performs predictions and visualization on the “test” data. For the 3D segmentation saves the images and segmentations as NiBabel file.

Roth HR, Lu L, Farag A, Shin H-C, Liu J, Turkbey EB, Summers RM. DeepOrgan: Multi-level Deep Convolutional Networks for Automated Pancreas Segmentation. N. Navab et al. (Eds.): MICCAI 2015, Part I, LNCS 9349, pp. 556–564, 2015.

Cancer imaging archive wiki. (n.d.). Retrieved February 06, 2021, from https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/display/Public/Pancreas-CT#225140409ddfdf8d3b134d30a5287169935068e3.

Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241.

Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning dense volumetric segmentation from sparse annotation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Athens, Greece, 17–21 October 2016; pp. 424–432.

Salehi, Seyed Sadegh Mohseni et al. “Tversky Loss Function for Image Segmentation Using 3D Fully Convolutional Deep Networks.” ArXiv abs/1706.05721 (2017): n. pag.

Pérez-García, F., Sparks, R., Ourselin, S.: TorchIO: a Python library for efficient loading, preprocessing, augmentation and patch-based sampling of medical images in deep learning. arXiv:2003.04696 [cs, eess, stat] (Mar 2020), http://arxiv.org/abs/2003.04696, arXiv: 2003.04696

https://towardsdatascience.com/finding-good-learning-rate-and-the-one-cycle-policy-7159fe1db5d6

L. N. Smith, A disciplined approach to neural network hyper-parameters: Part 1 -- learning rate, batch size, momentum, and weight decay, US Naval Research Laboratory Technical Report 5510-026, arXiv:1803.09820v2. 2018

https://github.com/fepegar/unet/tree/v0.7.5

https://github.com/albumentations-team/albumentations

https://github.com/fepegar/torchio

https://github.com/mateuszbuda/brain-segmentation-pytorch/blob/master/unet.py

https://github.com/hlamba28/UNET-TGS/blob/master/TGS%20UNET.ipynb

https://discuss.pytorch.org/t/pytorch-how-to-initialize-weights/81511/4

https://discuss.pytorch.org/t/how-are-layer-weights-and-biases-initialized-by-default/13073/24

https://github.com/joe-siyuan-qiao/WeightStandardization

https://discuss.pytorch.org/t/patch-making-does-pytorch-have-anything-to-offer/33850/11

https://discuss.pytorch.org/t/fold-unfold-to-get-patches/53419

https://github.com/davidtvs/pytorch-lr-finder

https://github.com/frankkramer-lab/MIScnn

Holger R. Roth, Amal Farag, Evrim B. Turkbey, Le Lu, Jiamin Liu, and Ronald M. Summers. (2016). Data From Pancreas-CT. The Cancer Imaging Archive. https://doi.org/10.7937/K9/TCIA.2016.tNB1kqBU