This is my submission for the Individual Project in the 3rd year @ City, University of London.

The project has achieved a mark of 85%.

Author: Adam Kaczmarski

The research compares the deserialization performance of textual and

binary formats using different programming languages. The components

communicate with each other to obtain the data and measure their

deserialization times. Alongside the author mentions the drawbacks of

the most popular standard and looks for an alternative approach.

The comparisons are conducted on two layers of a regular tech stack -

back-end and front-end. The backend contrasts two compiled languages -

Java and Rust. The frontend utilizes TypeScript.

Modern web applications rely on hundreds of services running on

thousands of servers. Every visit to a popular website triggers dozens

of requests. Based on the response, the site may behave differently for

each user e.g. suggest other products to buy (1). Popular

platforms share data to have the best recommendation for the user. For

example, Amazon could suggest products based on recent engagement with

sponsored posts on Instagram (2). The data passed between

services and users needs to follow common standards to make usage

easier. Furthermore, reading such a response has to have low latency.

High wait times to transfer the data could be a bottleneck in the

pipeline, eventually forcing the administrators to scale up the

production environment or make the developers improve, in the worst case

rewrite, their code (3).

The most popular format used on the web is JSON. Although it's easily

readable, JSON has its drawbacks. Parsing JSON payloads could be

resourceful (Explained in section 3.1). Alongside text-like payloads, other data

formats are non-human readable. They have to be deserialized on the

clients' end. Those approaches are less popular but could be much faster

to obtain the data and take less (byte)space during the transfer

(4).

A Binary JSON is an alternative to the textual format. It is utilized by

a Mongo Database to store data (5).

Nowadays, communities talk about the need for quick and reliable

application (6). By finding out the difference between data

exchange formats, it is possible to reduce the delivery time of pipeline

results to the user (7). In some cases, changing the format

could lead to a decrease in infrastructure costs. Some vendors offer

pricing by the amount of data transferred or CPU time usage

(8)(9).

It is hypothesized that the usage of BSON instead of JSON improves the

performance in data exchange between applications. This experiment

compares the performance of JSON and BSON formats using different

programming languages - Rust, Java and TypeScript.

Within this hypothesis, it is presumed that the binary format will

occupy less bytes reducing the size of the payloads.

The chapter contains a description of every product of the project. It is to help the end user understand the core functionality of each component.

Type Rust web server source code and executable binary

Description The files contain the source of a fully functional Rust web server. The author has created eight rust files counting 433 lines together. Alongside the source code are compiled binaries (one for Windows, second's for Unix-like systems) that start the server. Purpose Results reproduction and review of implementation methods Document reference Implementation - 4.3.2 Appendix reference Source code and instruction appendix 12

Type Java web server source code and executable jar file

Description This component includes Java files (407 lines) that combine the logic of the web server. It contains web configs, features and defined objects used for benchmarking purposes. There is also a compiled Java Archive that allows the user to run the web server. The Java archive can be launched on any system that supports Java installation. Purpose Results reproduction and review of implementation methods Document reference Implementation - 4.3.1 Appendix reference Source code and instruction appendix 12

Type TypeScript files, bundled static files and Apache server configuration

Description TypeScript and CSS files that create a simple UI interface to trigger the API calls from servers. The UI's logic is coded in a single file. The rest of the files are the components that style the UI. In total, there are 348 lines. The Apache configuration is to enable proxy pass between the frontend and backend servers. Purpose Results reproduction and review of implementation methods Document reference Subchapter 4.4 Appendix reference Source code and instruction appendix 12

Type Python, JavaScript files and benchmarks results

Description Scripts to generate the graphs and CSV files. The server benchmark script gathers the parsing data from Java and Rust servers. Whereas the UI benchmarking script spawns a synthetic client that opens the browser, performs actions and gathers the parsing time from the paragraph. The materials include the obtained files and produced charts. Purpose Automated benchmark reproduction and data gathering over larger scopes. Benchmark results overview. Document reference Implementation discussed in subchapter 4.5. Appendix reference Appendix 11

Type Text documents (Dockerfiles and docker-compose file)

Description Text documents containing commands to build executables and Docker images. Those combined with the docker-compose file will spawn the containers required to run the tests. In total, there are 101 lines of instructions. Purpose Application deployment for reporoduction Appendix reference Appendix 12

The chapter contains a review of relevant papers that help to understand the domain problem. It was done to identify expectations of the research and gain knowledge on how such experiments were conducted in the past.

JSON is a lightweight, text-based interchange format. It is one of the most popular communication formats (10). JSON can represent basic primitive types such as number, boolean, string, null and two structures: arrays and objects. The data is stored in a key-value format. We can access the value by using the named field/key (11).

When exchanging JSON data between systems, the text must be encoded using UTF-8 (12)

A UTF-8 string is made of a sequence of octets representing UCS

(Universal Character Set) characters (21).

(1 octet = 1 byte = 8 bits)

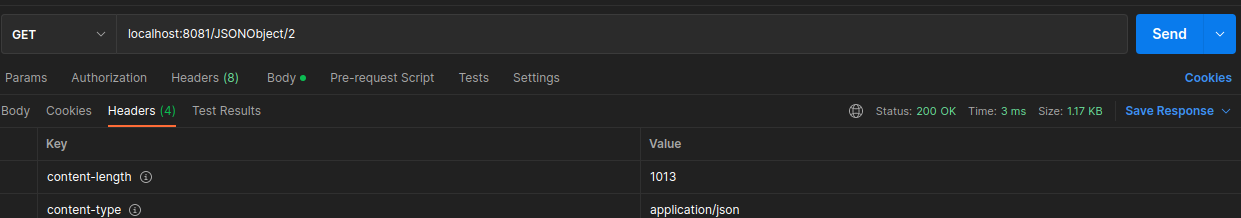

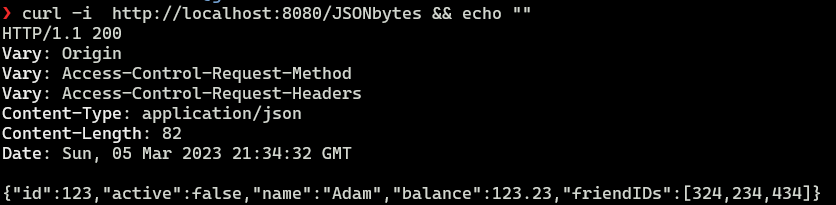

A JSON payload containing object:

{

"id":123, // 7 bytes bytes

"active":false, // 13 bytes

"name":"Adam", // 11 bytes

"balance": 123.23, // 15 bytes

"friendIDs": [324,234,434] // 21 bytes

}

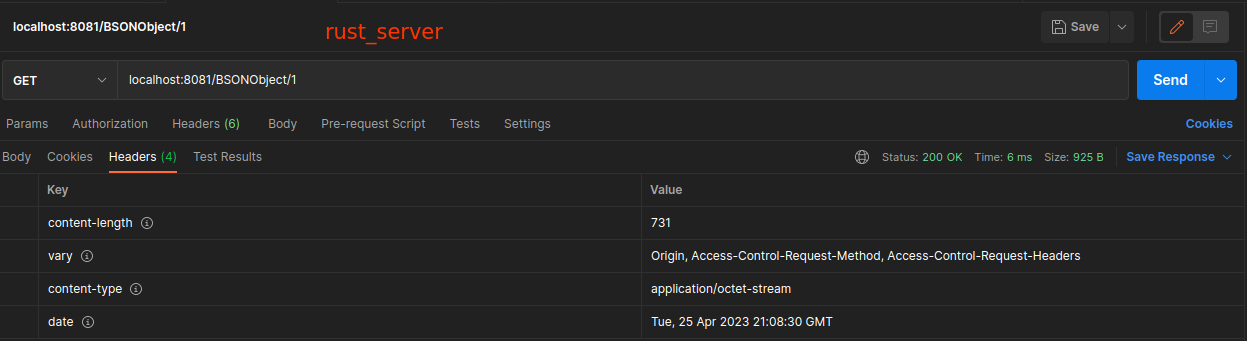

will occupy 82 bytes. It can be confirmed when requesting such an object from the server. The response contains a Content-Length header informing about the byte size of the body.\

For a program to consume the JSON response, it must parse the whole text, all bytes, before the object could be used in further execution. (12)

JSON is a schema-less data format (22). That means it does not require any declaration of the included fields on communication ends. The structure of a document has to comply with the determined set of grammar rules (11). Today JSON has many usage scenarios such as:

-

Configuration files,

-

Logging,

-

Intersystem communication,

-

Database storage.

Binary JSON is a binary encoding format of JSON-like documents. The

implementation expands the data types of JSON. It allows specifying

exactly the byte length of fields (13).

For example:

A field of type int32 will only take 4 bytes in binary representation

and can store a number up to 2147483647. The same number encoded in JSON

would take 10 bytes of space. The same is for boolean values that occupy

only 1 bit in binary but take 4*(true)* or 5*(false)* bytes when encoded

in JSON (12).

As shown above, many BSON types are stored at a fixed length. It allows

parsers to skip bytes to obtain the searched field in the document.

(13)

The format is utilized in one of the most popular NoSQL databases - MongoDB (5).

The paper 'A benchmark of json-compatible binary serialization specifications' (2022) investigates the byte occupancy of various data formats. In most cases, it was found that BSON occupied more bytes than JSON documents. The authors have classified their files into three categories: textual, numeric, and boolean. They observed that the data sets are dominated by string values. In some cases where numeric values were the majority, BSON occupied less space. The paper also considers compression algorithms which are not considered in this research. (14)

The authors of the paper 'Improving performance of schemaless document storage in PostgreSQL using BSON' (2013) extended PostgreSQL's feature to store JSON files by implementing BSON serialization. They focused on the traversal aspect of those two formats. Commonly databases are queried only to obtain a small number of values stored in the database. The contributors have taken the BSON possibility of encoding the byte length of some types and implemented that for PostgreSQL. BSON stores strings in the same manner as its schema-less predecessor. Thus, there is not much difference in the row size for textual values. The numeric data helps the database reduce the size of its rows.

Although the storage difference might be unnoticed, it is the query latency that the developers wanted to reduce. JSON data is stored in plain text and has to be parsed fully to obtain data from queried keys. When the same data is stored in binary representation, the authors noted that their queries were up to five times faster. The possibility to skip bytes helps the application find the data faster and reduces the disk's utilization. (7)

In the past, when JSON was pushing XML out of use, similar papers to the current one have been made. The study 'Comparison of JSON and XML Data Interchange Formats' (2009) contributed a lot to the core understanding of this research's methodology. The authors measured response times and tiresource utilization when sending/receiving large amounts of objects. While doing so, the servers were monitored to compare the resource utilization in the future. As XML is a mark-up format that requires a sizable amount of text to be transmitted, JSON took the lead with its schema-less approach. The result was that JSON communication was almost 300% faster in comparison to XML (15).

This project accommodates a similar approach as it is modelled to mirror the applications' flow of consistently requesting data from other services (1).

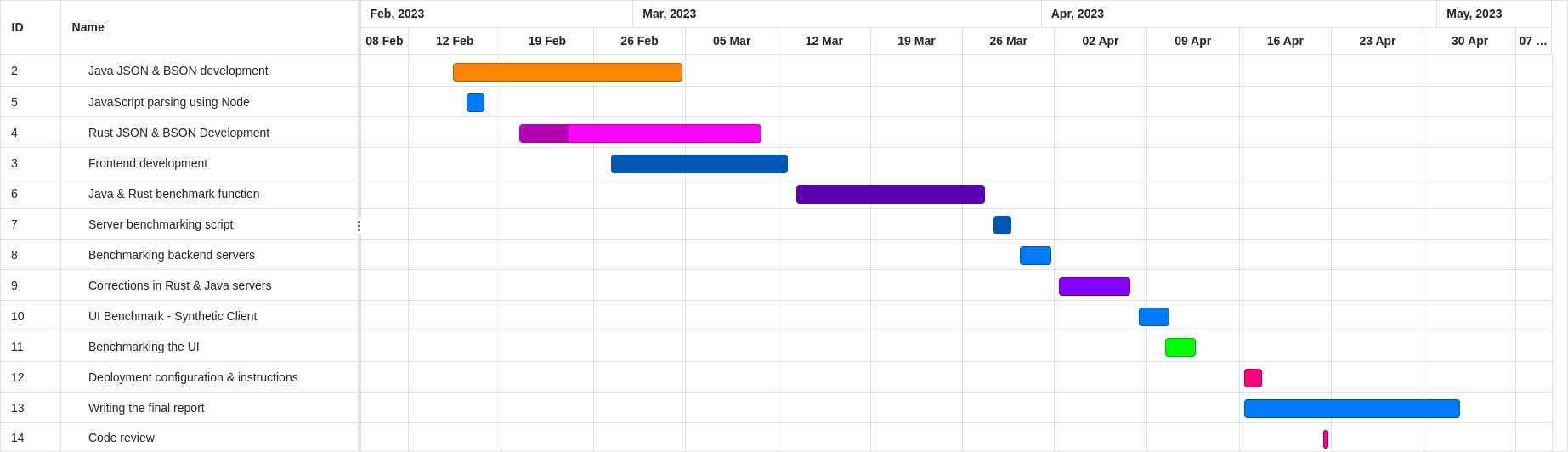

The chapter describes the methods used to achieve the products of the project. The author has decided to follow the agile approach. The discovery of the domain problem required knowledge of serialization. Thus, the code changes were tested continually. The number of features was manageable to cover. The results had to be verified as sometimes they led to code adjustments.

It has been decided, in the experiment as the test data the applications

will transfer less complex generic values that can be found on modern

platforms.

For example, each Twitter profile entry downloads a large JSON file.

There are two types of objects. One called DummyObject that's fields are

mainly of type String and the second one, called NumericObject, consists

of number data (integers and doubles). Each of those schemas has a

sub-schema to add complexity to the data. For the textual object, it is

DummyFriend, and the numbers dominated one includes Coordinate. The

definitions are in appendix 9. For ease of readiness, those schemas are

in TypeScript interface definitions. Each application had its

implementation of both models with respective data types.

The test data was generated and coded into the application launch.

Therefore, the servers had equal data sets. Java's objects

initialization code can be found in appendix

10.

During the development of the front-end client, Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) had to be disabled on both servers. The security measure blocked access to the endpoints for local development and was enabled by default. Disabling it allowed the applications from various ports to access the resources. For example, localhost:5173 could not access the endpoints of the Java server running on port 8080 due to CORS.

At the beginning, the dependencies were added to the project. For JSON

serialization it was Jackson,

for BSON, Mongo's implementation was used - Java BSON

library.

Initially, it was challenging to serialize the Plain Java Old Objects

(POJO) to a BSON Document. The library allowed the creation BSON

Document from a JSON string but did not allow the production of a

document using the object itself. Therefore it was essential to either

save the object into String format and then to binary or to find another

dependency that helped to omit those steps. Fortunately,

bson4jackson

implements such functionality and enables BSON serialization in Jackson

methods. Spring Boot Starter Web provides the web functionality of the

application. It embeds Tomcat to handle requests and provides

easy-to-implement features such as Remote Procedure Call (RPC)

controller called RestController. The next step was to create a health

check endpoint. It returned an empty response from the server to

establish an initial connection. When its return status was eqaul to

200, the server was running.

At first, all of the endpoints returned the DummyObject. Later on, the

endpoints were parameterized, documented in

5.3, so

the code would not have to be changed to test different structures.

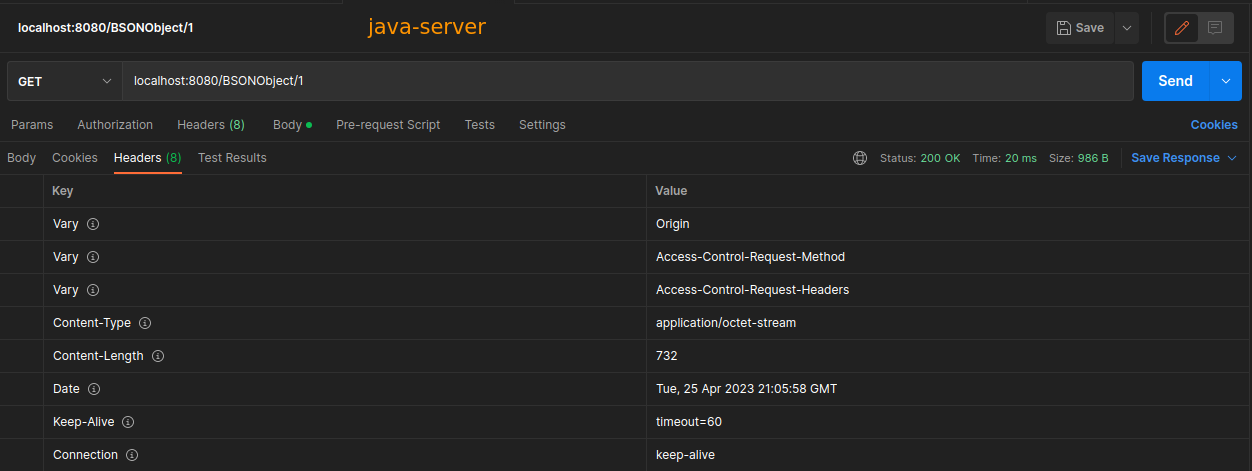

During the lifecycle of the application

Postman and curl were

used to test the correctness of the endpoints.

The JSON serialization was one of the first main tasks accomplished as

Jackon's ObjectMapper processed the entity into a string using a single

function. Although BSON's serialization was very timely to achieve, two

approaches have occurred. In the first one the object was encapsulated

into a JSON string, then to RawBsonDocument and finally encoded into a

byte array. This implementation had flaws as it required the application

to write the object into a JSON string. The method went against the

exepriment's objectives of not operating the text format. The second

approach of creating the binary response was to utilize bson4jackson.

The library reduced the complexity of the code and was easy to use.

The last fragment of the application was to deserialize the objects in

both formats. To ease the automated testing triggerReqs endpoint was

created. As the name suggests, the interface was used to start the

action on the server. More about the testing in chapter

4.5. The function required parameters,

explained further in chapter 5.3, to run the test. A simple Data To Object

(DTO) helped to encapsulate those into a single data structure. At the

start of the function, the object holding the results had to be created.

The endpoint returned it in a JSON format, which helped a lot during the

automated testing.

When the function was called, the server requested objects from the

specified provider and measured the parsing time of the data. The

deserialization time unit had to be microseconds as sometimes the

parsing time of fewer objects took less than one millisecond. The timer

started upon the response and stopped after the data was decapsulated,

given that the program had the structure already defined. For JSON,

again, Jackson was used to deserialize the string into the desired

object.

There were two approaches to deserialize the BSON byte array. BSON

library could easily instantiate a RawBsonDocument but could not cast

the document into the desired object. It meant that the fields, of a

deserialized object, could not be accessed directly. This approach

worked much faster than its alternative. Bson4jackson's mapper provides

such method and access to the response's fields was possible. The

prototype's parsing times of those two approaches, when requesting ten

thousand DummyObjects from rust_server, are presented below.

bson4jackson

{

"rust":1,

"amount":10000,

"bson_parsing_time_micro_s":432484,

"bson_total_time_ms":1455

}

RawBsonDocument

{

"rust":1,

"amount":10000,

"bson_parsing_time_micro_s":28268,

"bson_total_time_ms":1059

}

Although Mongo's feature was around fifteen times faster, having the

desired object instantiated and its fields accessible was decided to be

more advantageous for the experiment.

The same applies to the JSON format. JsonNode would share its API over

to the transferred String but direct access of object's properties would

be impossible.

The objective was to compare the parsing times using two distant

compiled languages with distinct memory management mechanisms. Rust's

ownership system has nothing in common with Java Virtual Machine's

garbage collection.

The fundamental web server with a helath check endpoints was implemented

in reference to the book Zero To Production (2022) by Luca

Palmieri. The text suggests one

of the most popular web frameworks called actix

alongside the most popular asynchronous runtime -

Tokio to build a web application.

In Rust, dependencies are referred to as crates (16). To

serialize and deserialize the structs (objects) serde, serde_json and

bson crates were used. The latter two are an addition to the mentioned

serde. The framework is a generic layer that allows other developers to

create parsing libraries on top of that (17).

Similar Java server's development, the first created endpoint returned a

JSON string. It serialized the struct into the textual format using only

one line of code. At the start, all the startup-initiated structs could

only use string slices due to the memory management of Rust. A string

slice is an immutable string value. It is an address to a specific point

of the binary. The Rust language is very efficient because it stores

static data on a stack whereas dynamic data, data that can change during

runtime, is stored on a heap. The string type is a vector of bytes. It

can change its size at any time. (16) Therefore, any string

variable has to be initiated after the program is compiled. The Tokio

runtime allows users to define dynamic global values in the code. The

objects are built by additional functions that return or initialize the

object (18).

Contrary to Java's BSON solution, serde and bson can serialize any value

into RawDocumentBuffer. It can be saved as an array of bytes.

The benchmarking function implementation is very similar to Java's one.

The required parameter is a JSON string with parameters that the

application uses in its tests.

After constructing BSON document from bytes, serde creates an object based on the specified type. Therefore, after reading the octets, the fields were accessible without an additional dependency. The story for JSON is very similar. serde combined with serde_json deserialized the payload into an accessible struct. A single function returns the object. At first, tests on a smaller quantity of objects resulted in 0 ms of parsing time. It was observed that Rust performed much faster and used microseconds.

The web application used ReactJS, one of the most popular JavaScript

frameworks (19). TypeScript provides type safety and the

possibility to create subtyped structures. The language is a superset of

JavaScript. It provides static typing that helped the developers to

detect bugs during the implementation. The serialization is handled with

MongoDB's BSON package.

At first, the NodeJS script was written to deserialize a BSON response.

It was reasonably easy to do as the Node's environment supports buffers

that help to read the byte array from the body. Such buffer, was used to

create a byte array. The BSON library deserialized the vector into

documents. Unfortunately, the Buffer implementation limited to the

NodeJS environment. Therefore, it's not accessible in the browser.

A proper environment has to be picked to develop a React application to

supply hot reload and quick build times. ViteJS

provides runtime with a very low latency.

The front-end goal of the application is to request data and parse them

into a specified structure. The objects are not shown in the UI nor

used. They are swept right after they move out of scope. The

axios package was introduced to handle the

asynchronous requests to the server. The drawback of the implementation

was lack of the byte array feature. Therefore, it could not be extracted

easily from the response body. JavaScript's fetch allows receiving the

payload as a blob (Binary Large Object) that includes an arrayBuffer

method. The buffer was used to create an UInt8 Array that the BSON

library used to deserialize into the defined, typed interface.

TypeScript's interface allows the developer to access the fields in the

structure.

JavaScript Object Notation is a part of JS and TS. Therefore the

serialization methods are a part of fetch's interface.

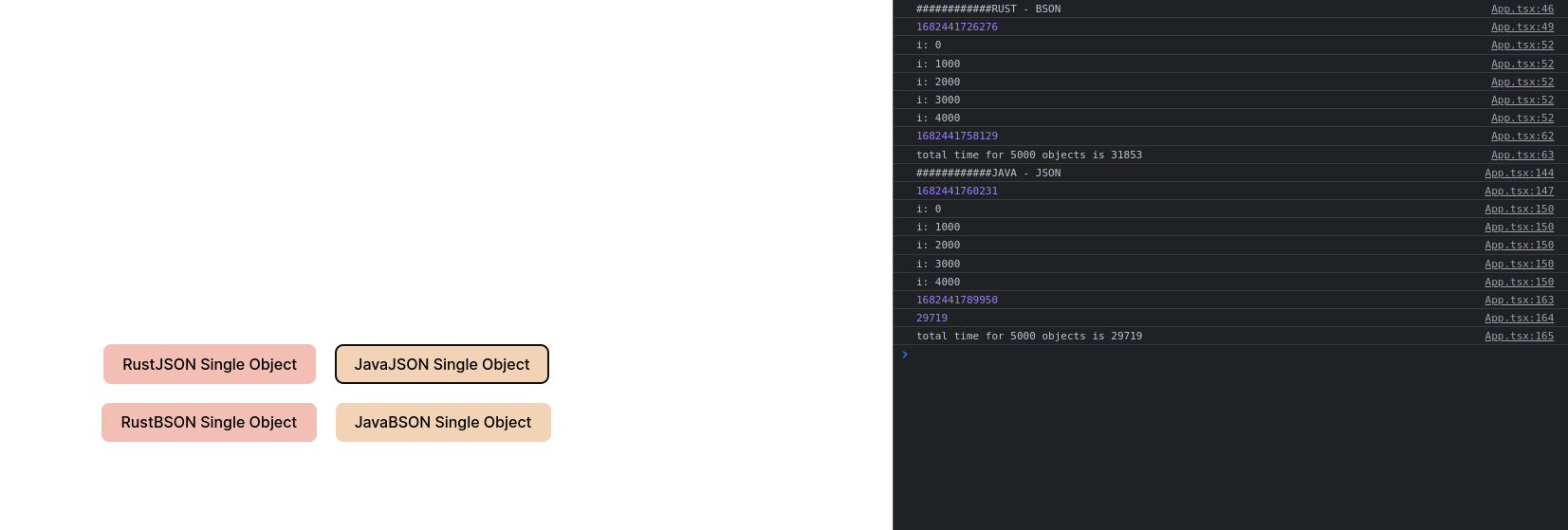

The first version of the UI had only buttons that, when clicked,

executed a function to get the objects. The parameters, such as the

number of objects, were hard-coded and adjusted inside the code. The

parsing time was measured using milliseconds and logged into the

browser's console.

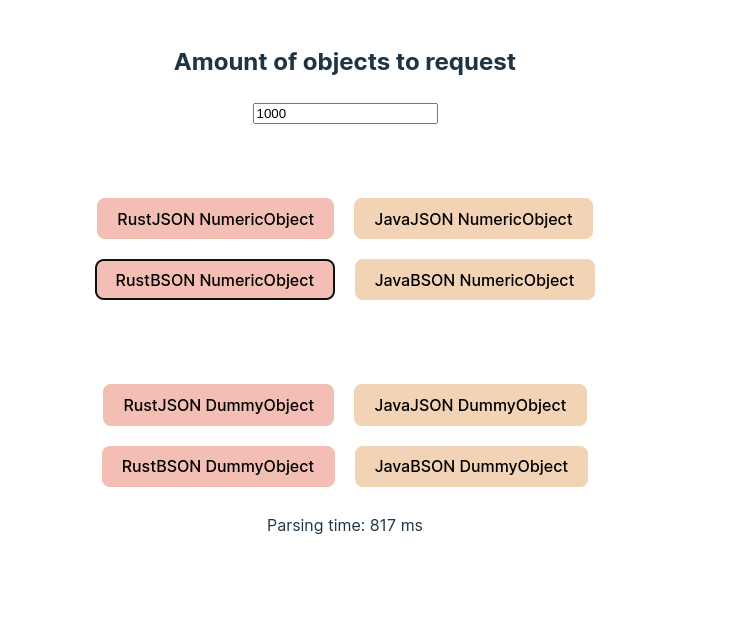

Further into the project, to automate the benchmarking more buttons were added, for each server, object type and the object's serialization format. The parsing time was shown underneath the buttons, and input was added to specify the number of objects our application had to request and parse.

The UI has been styled using regular CSS. The simple interface provided everything required to measure the parsing time of the test data.

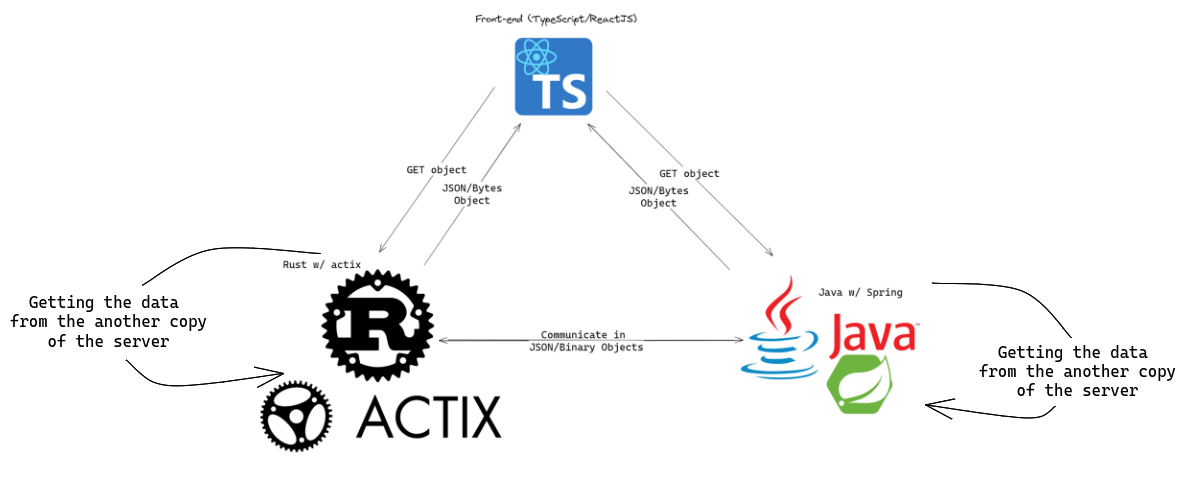

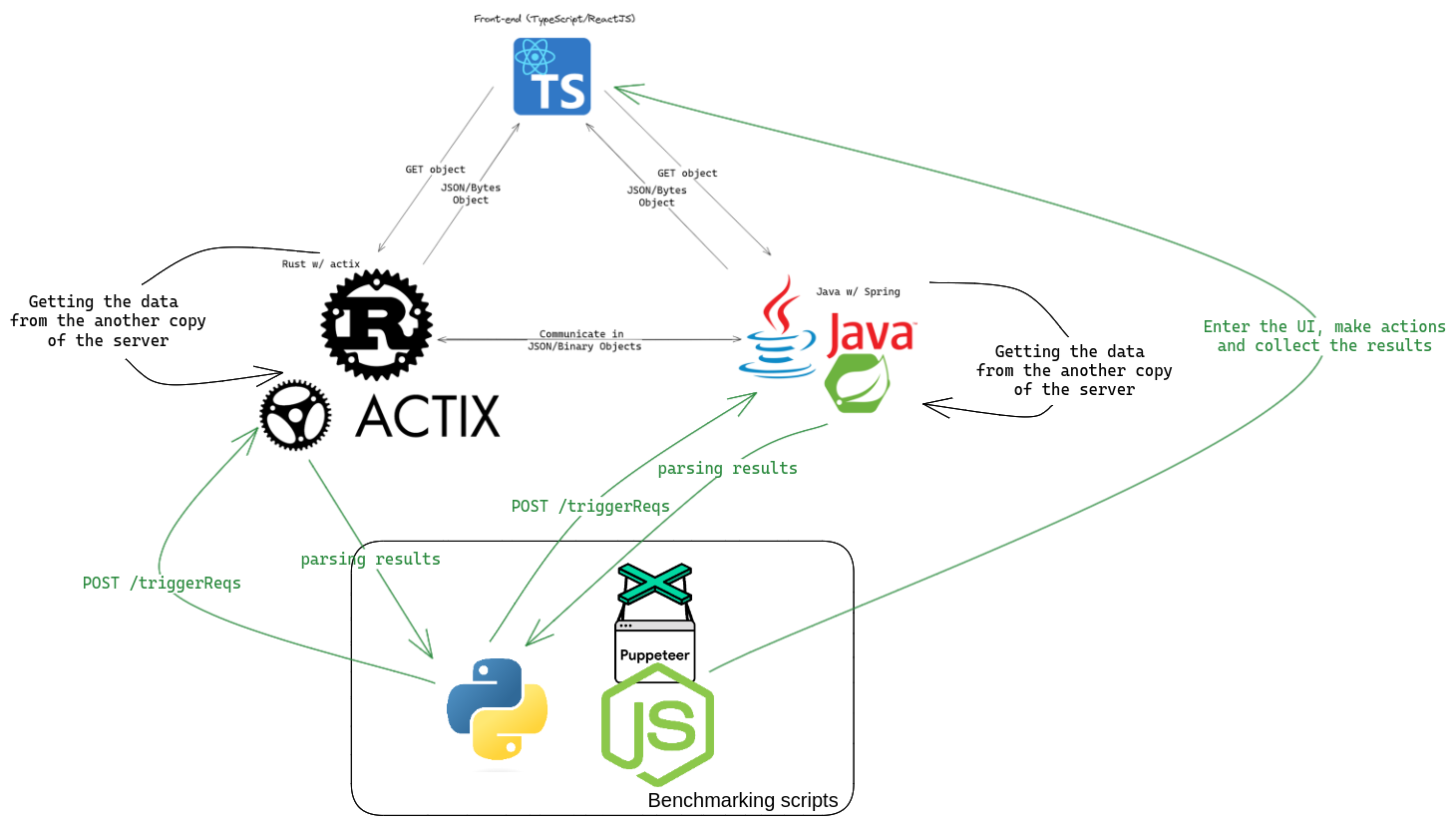

The chapter describes the benchmarking implementation and techniques used to obtain the results. It also explains the components and how they communicate with each other. The graph below (fig. 4.4) presents the visual relationship between them.

The author decided not to operate on a personal machine to perform the

benchmarks. Individual systems have many services running based on user

behaviour. Those sometimes unexpectedly consume a lot of the available

CPU time or memory. Additionally, to not cause any slowdown, the machine

would have to be left running without any human interaction. The

decision was to use Virtual Machines (VM) provided by Google Cloud.

Those installations had no users interacting with them and could be left

running for nights without concerns whether the developer's machine was

on. The machines were accessible via ssh, and files were uploaded using

scp because the installation did not include any graphical user

interface. Screen command was used to execute the benchmarking scripts

without an active session to the server's terminal. It allowed the user

to detach from the current terminal session, leaving it running. The

user could reattach at any point in time.

To carry out the benchmarks, two virtual machines were created. The

parameters are as follows:

-

The backend server

-

Hosted in zone europe-west-1.

-

The GCP machine type: e2-standard-2.

-

CPU: 2 Cores of Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU @ 2.20GHz

-

Available RAM: 8GB

-

Running OS: Ubuntu 22.04.2 LTS (Jammy Jellyfish)

-

Kernel Version: 5.15.0-1032-gcp

-

-

The user server [[userServer]]{#userServer label="userServer"}

-

Hosted in zone europe-southwest1-a

-

The GCP machine type: e2-standard-2.

-

CPU: 2 Cores of Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU @ 2.20GHz

-

Available RAM: 8GB

-

Running OS: Ubuntu 22.04.2 LTS (Jammy Jellyfish)

-

Kernel Version: 5.15.0-1032-gcp

-

Google Cloud Free trial credits have covered the payment for the machines. To not obtain unnecessary additional costs, those VMs were disabled after acquiring the results.

To conduct the parsing benchmark between JSON and BSON formats, the

triggerReqs endpoints, mentioned in

4.3.1 and

4.3.2, were

utilized.

Initially, the functions had hardcoded values instead of parameters and

logged the results instead of returning them. The user only needed to

call the endpoint with the number of objects to obtain. The requests

were triggered by a simple bash script. It used curl to start the

procedures on the servers. After the action, the author had to collect

the logs from the server and hand pick the results.

Rust was performing two times slower than Java when one million objects

were to be parsed. The conclusion was that Java was serving the requests

at a much slower rate - the results of the tests are in appedix

14. There were a couple of factors:

-

JVM's garbage collection

The higher limit of the JVM's heap was not specified. That enforced more aggressive garbage collection on the environment. During the early tests, the serialization happened with each request. When those created objects added up, they had to be swept to release memory.

The solution was to set the max heap to 1024 megabytes. The GC pauses rate was much lower. -

Slower serialization

-

Was Rust performing worse?

It was determined that the Rust build profile was a development one. A

proper parameter had to be provided to cargo, that is Rust's package

manager, to create an optimized binary. It improved the service time.

The next benchmark with

ab, apache's

simple command line application to test HTTP servers, confirmed the

results. The test was conducted using one thread that sent one million

GET requests on /JSONObject and /BSONObject - the results are in

appendix 15.

During the investigation, it was decided to take the requesting line of

code out of the measurement window, from between the start and stop of

the timer. The goal of the project was to measure the parsing time, and

the server's networking performance could be an obstacle adding

disruptions to the benchmark data.

When requesting the objects to parse, it was decided to spawn two

servers that acted only as providers. Those were to return data to the

original applications. This way Java could also request from another

Java service and vice-versa. Two new services were only to check whether

the processing of GET requests impacted the parsing. For example, the

Java server, due to Spring's implementation, was returning four more

headers than the Rust server. Additionally, the Spring's implementation

included embedded Tomcat which acts as a HTTP web server.

When the environment was ready to be benchmarked, the developer created

a Python script that sent POST requests to the servers. It gathered the

result data into a map and ran in rounds. Each round performed the same

action. Each key, number of objects, held its average parsing time. The

script had to have a specified amount of objects that the server should

request and parse. The loop incremented the number by five hundred until

a hundred thousand. When a request was serviced by the application. It

sent the specified amount of API calls to the provider server. For

example, when rust_server had received the URL of the java server

provider with the amount of four thousand. The rust_server would send

the same number of requests to the java server requesting the object.

Then, the sum of the parsing times was returned to the original

requester - the Python script. For each finished scenario, the script

created a CSV file with the map data and generated a graph to visualize

the results.

There were sixteen scenarios in total.

A one scenario was a combination of these elements:

-

Parsing server - rust-server, java-server;

-

Provider server - rust-server-provider, java-server-provider;

-

Object type - NumericObject, DummyObject;

-

Object format - JSON, BSON.

The automation to obtain the parsing results from the React application

was achieved using a synthetic client. The goal for the user was to open

the browser, trigger actions in the interface and obtain the demanded

results. Many frameworks enable such scripting possibilities, such as

Selenium,

Cypress and

Playwright but Puppeteer

was the best fit for such a simple scenario. Puppeteer is a Node.js

library that provides API to control the Google Chrome browser

(20). The script was launched from the terminal using

NodeJS. It triggered the testing function for each hundred until it

reached the upper limit - default wass set to five thousand which

equalled fifty executions. The synthetic user's scenario was to open the

browser, input the number of objects to request, press the button and

wait until the parsing time results appeared on the screen. For the

execution to be successful, identification labels had to be added within

the application's code. The script would press the buttons or read the

values from components with the IDs assigned in the Document Object

Model (DOM). For the results to be more precise, the benchmark ran in

rounds. By default, each scenario, made for each server provider, object

type, object format, was triggered three times. An average of each test

result was calculated. At the end of the last round, the map was saved

to a CSV file to generate the graphs.

During longer runs, when more objects were procssesed, Puppeteer would

timeout. Those default events had to be disabled.

Based on the data from JavaScript's execution, the charts were generated

using Python. The script used pandas to

read the data and matplotlib to plot the

charts.

The benchmarking of the front-end application was conducted on the user

server. The synthetic client accessed the backend's server

Apache2, which served the static files and

acted as a proxy between the user and the Rust & Java applications.

The diagram below (fig. 5.1) presents the products of the project and their relationships.

The fully working product is capable of serializing and deserializing objects using BSON and JSON. The package contains a controller with functions to execute via API. Spring's instrumentation made it possible to route those procedures to the named endpoints using annotations. For example,

@GetMapping("/BSONObject/{objectType}")

@GetMapping("/JSONObject/{objectType}")

Each route has to be accessed using the IP of the server, 127.0.0.1 when

launched locally followed by the bound port which by default is 8080

unless specified otherwise. The JSON serialization of the objects has

been achieved using the Jackson library. To convert objects to binary

representation, the author utilized bson4jackson. It added the required

functionality to the already-used dependency.

To conduct the measurement of parsing the objects in various formats the

benchmarking function will request a single structure from the specified

location. It will repeat the action for the defined number and sum the

times. After the action is completed, it will return the results.

Additionally, the server included test object definitions and initiated

them with the data during the launch. A single encapsulation has

improved the server's latency and did not trigger aggressive garbage

collection.

The Rust application has the same functionalities as the Java server. By

default, the software binds to port 8081, which can be modified using

the launch parameter or alternatively the environment variable. The

actix framework provided web functionality. The tokio runtime added

asynchronous features to serve requests on separate threads. The

structs/objects definitions are in separate files for easier visibility.

Those are initialized with the test data (appendix

10) when

accessed for the first time through Tokio's OnceCell feature. Such

behaviour is due to Rust's memory management. It is explained in the

methodology chapter 4.3.2.

Serde framework handles the serialization of the structures. Additional

crates, serde_json and bson, enabled the desired format's

functionality. Due to the speed of compiled language, the parsing times

were measured using microseconds. In of most the test trials the

deserialization of a single object took less than a millisecond. It used

to gather false data where one could think that thousands of objects

were resolved without any latency.

The chapter contains the endpoints documentation of Java and Rust servers. Two routes have different paths which is marked in the text.

-

RUST:

GET /health_check

JAVA:GET /healthCheck

Returns the code 200 if the server is running. The response body is empty. -

GET /JSONObject/{objectType}- objectType Number specifying the type of requested object. The allowed values are 1 or 2 that represent NumericObject and DummyObject respectively.

The endpoint returns a JSON string representing the object.

-

GET /BSONObject/{objectType}- objectType Number specifying the type of requested object. The allowed values are 1 or 2 that represent NumericObject and DummyObject respectively.

The endpoints returns the byte array representing BSON Document.

-

RUST:

GET /json_bytes

JAVA:GET /JSONbytes

The endpoint return a simple JSON string. It was created only to showcase the amount of bytes consumed by a JSON response. -

POST /triggerReqs

The endpoint requires a JSON payload of structure:{ amount: number, //Amount of objects to request from provider_url provider_url: String, //The server to rquest objects from object_format: String, //The format of requested objects, allowed values are either "BSON" or "JSON" server_type: String, //The server type of provider_url object_type: String //The type of object to request, allowed values are either "DummyObject" or "NumericObject" }The endpoint return a JSON string containing the number of requests objects, total time of the action in miliseconds, the parsing time in microseconds and type of the provider server. Field "java":1 will mean that the objects were requested from Java server).

The web user interface objective was to request an object from one of

the servers and deserialize it into usable data. The TypeScript

interface feature allows the developer to add static types to a

structure. The application does not use the data. The goal was to

measure the time spent in the object deserialization process. BSON

package has provisioned the Binary JSON parsing features. The rest of

the functionalities are from core JavaScript. Regular CSS styled the

UI.

The application has eight buttons that request the earlier specified

number of objects via input field. Those are requested from the server

that provides the front-end static files. After the objects are

received, the parsing time is displayed. ReactJS has added the

possibility to manage dynamic content.

The project's components can be deployed using two approaches.

One is to run the binaries manually. Each server has its compiled file

that will launch the application. The front-end's static files have to

be served by a web server such as Apache HTTPD or

nginx with proper proxy configuration to the

Java and Rust applications.

The other approach used Docker to compile the

software and build images. Those packages will have the necessary

runtime dependencies and tools. They are used to create the containers.

Each of them executes everything it needs to run the application. By

using the defined docker-compose files the containers can request each

other utilizing the internal network. Each of the components is

accessible by the host on the exposed port. The documents simplify the

process required to deploy the project's stack.

The instructions for both approaches are included in the code package.

The Python script benchmarked both servers. It went through every

scenario three times and calculated an average of the parsing times

returned by the applications. There were sixteen scenarios for the

backend testing - mentioned in chapter

4.5.2.

The script was launched on the backend VM and the programs communicated

using an internal host network via HTTP. With each finished scenario the

graph was generated based on the gathered data. The outcome was saved to

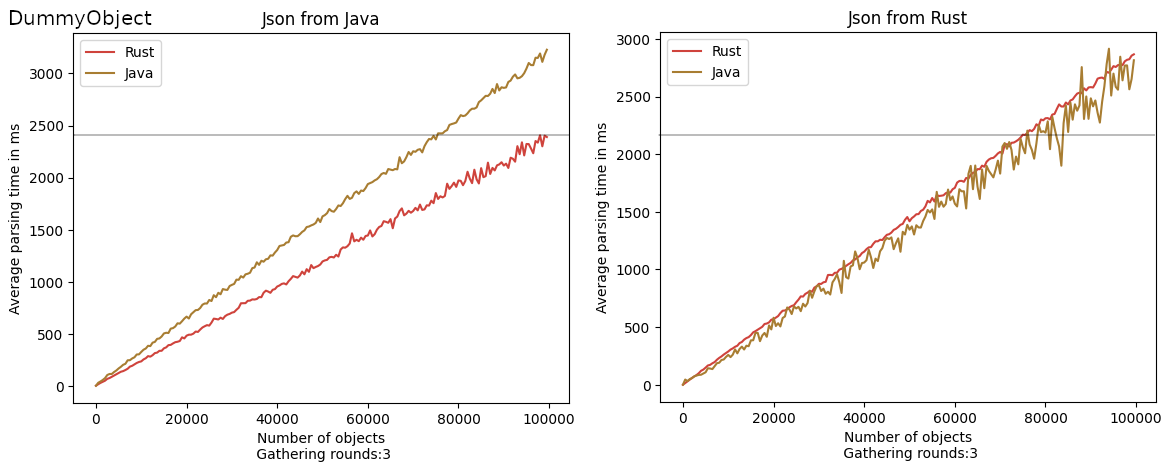

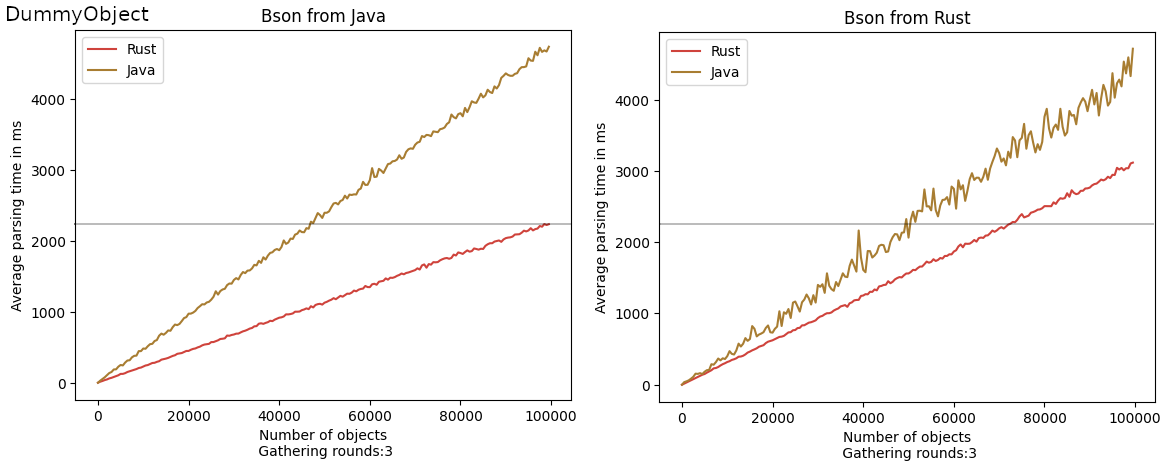

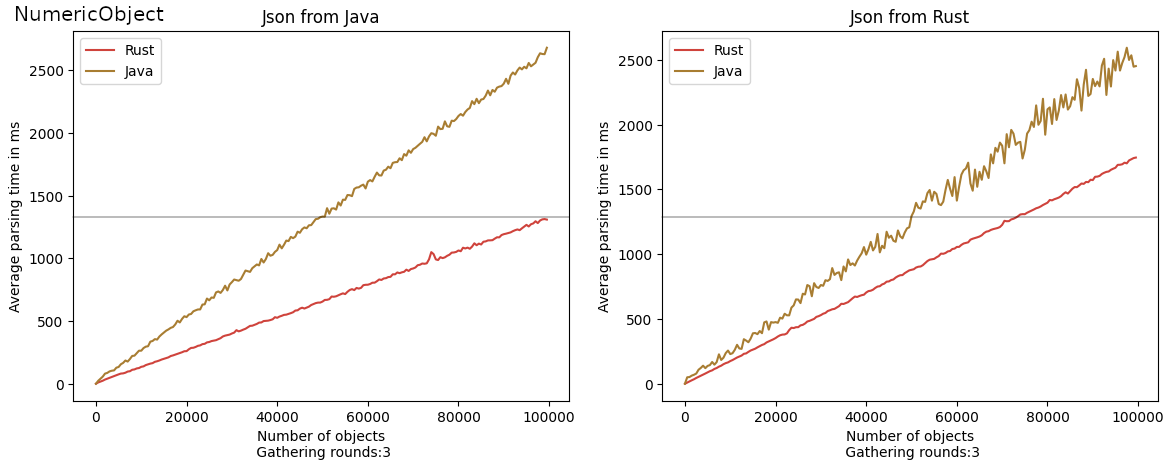

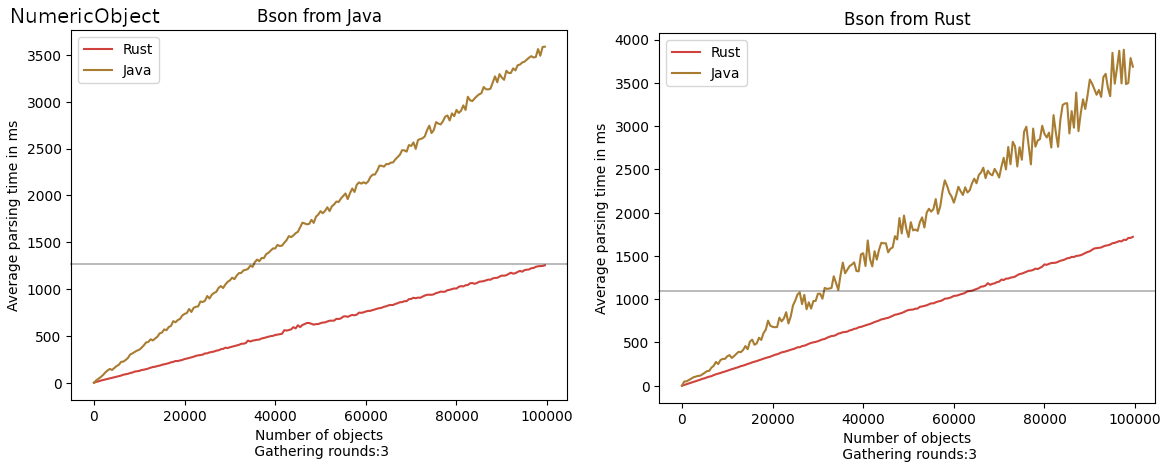

a CSV file. Below are the graphs presenting the results of three rounds

of parsing up to one hundred thousand objects of each format from both

applications requesting different providers.

The grey line is to mark the lowest deserialization time using Rust, to compare the results from different providers.

From the charts, the BSON format takes more time to deserialize by around a second when using Java's implementation. On the other hand, Rust's times are very close to each other - around two and a half seconds when one hundred thousand objects are requested from Java and around three seconds from another Rust instance. Noticeably, when the objects were requested from Spring's web server, Rust performed much better.

The grey line marks the lowest deserialization time using Rust to compare the results from different providers.

The deserialization time of the structure dominated with numbers was

much lower using JSON for Java. Whereas, Rust has went equal using both

formats from both providers. Although when the requests were served by

the JVM representative, Rust handled those much faster.

The Java implementation had much more latency in processing the binary

format of the structure. JSON parsing would be a much better choice to

transfer the data.

The Rust approach has been even using both formats, the difference is

hard to spot. It can be noticed that when the objects were requested

from the Spring's web server, Rust performed much better. The

application's behaviour is very intriguing when using two different

providers.

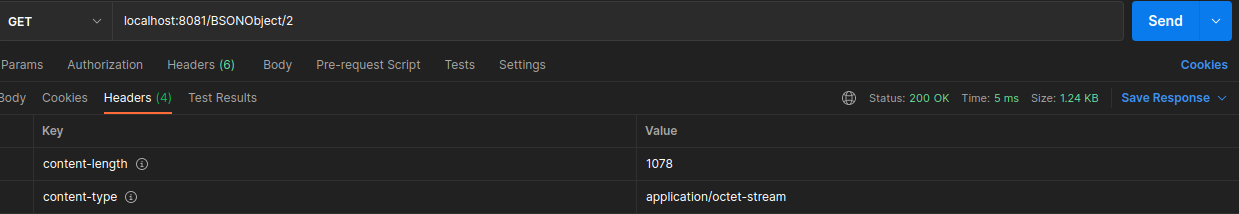

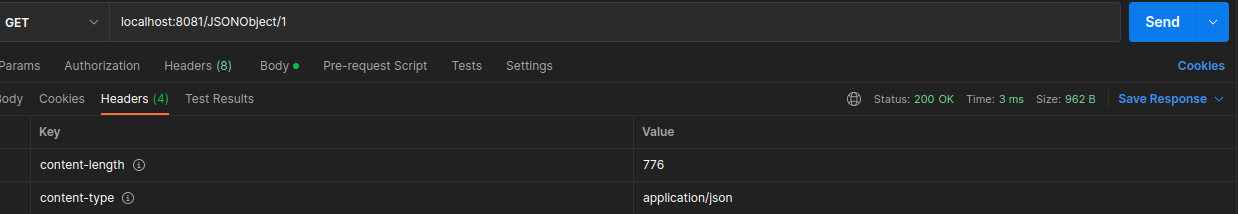

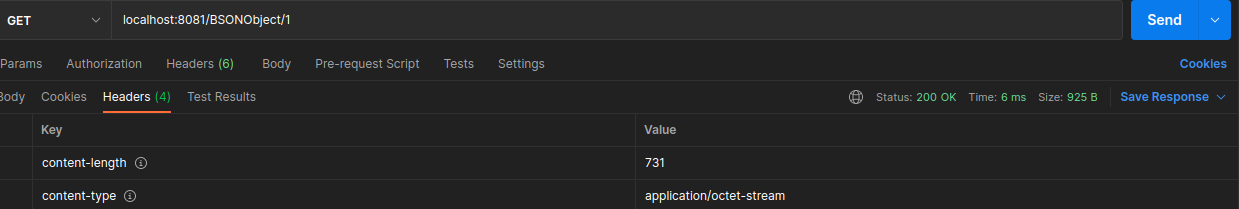

As anticipated in chapter 3.3, the NumericObject has taken fewer bytes in its binary form. Whereas the BSON DummyObject took more space than JSON. On the figures below, the occupied octets are displayed in content-length header.

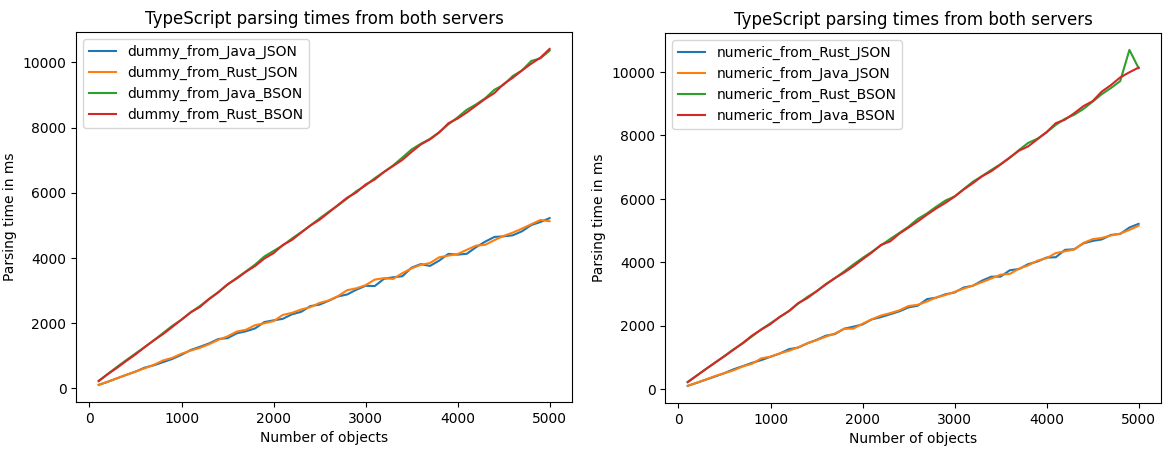

The front-end application had only eight scenarios to cover. Each button covered one of them. The synthetic client acted similarly to the Python script. It ran three rounds of data gathering over the incremented number of objects to parse. After the last round, the gathered results were saved to CSV files. The outcome was visualized, using a Python script, in two separate charts for each object type.

As pictured above, the JSON format has been two times faster than it's binary alternative. The change in providers did not impact the deserialization times. The NumericObject's processing was marginally faster because it had fewer bytes.

The project's goal was to examine if BSON improves the performance in

data exchage. Additionally, the author wanted to analyze the performance

using different programming languages on two layers of the tech stack.

The front end used TypeScript. For the back end, two different compiled

languages were examined against each other. The distinction was memory

management. Java uses garbage collection and Rust utilizes the ownership

system.

The benchmarking chapter (5.6)

discussed that Java could not create objects

from BSON payloads with a better latency. While Rust had similar times

for both formats. Java's implementation was the only one that has not

used MongoDB's BSON dependency, as it was challenging to initiate

objects with it. The open source library has enabled such feature for

Jackson. Perhaps, the times would be much better if the library from

Mongo could initiate objects from the documents by itself. Such feature

exists when obtaining the documents using the Java driver to connect to

the Mongo database.

The back-end test has shown that Rust is performing much better than

Java. The deserialization of the binary structures was around two times

faster. Rust's JSON parsing has been quicker in all cases exept figure

5.2

where the results were equal for both languages.

As there are some possibilities to introduce Binary JSON to the compiled

environments, the TypeScript application did not manage the parsing very

well. For both object types, the textual deserialization was twice as

fast as its contender.

The binary resolving required the developer to use a blob object to

obtain the byte array. The JavaScript/TypeScript front-end environments

did not seem well equipped to handle the binary payloads. It might be

better to convert the structures to a JSON format that does not require

pre-defined interfaces.

The latency on slower platforms could be caused due to the way BSON

serializes the data. As mentioned earlier in the literature review

(chapter 3.3), the NumericObject have occupied less space in

its binary form but the DummyObject was not that fortunate. The string

type in the structures is serialized the same way as in JSON.

Unfortunately, BSON does not support smaller integer formats such as

int8. The lowest integer type that BSON supports is int32. That's twenty

four more bits than some fields required. Perhaps the objects would take

even less space if smaller types were supported.

The unexpected finding was that Rust handled the parsing time much

better when the data came from the Java server. It was envisioned that

the times would be equal or that the Rust response will be handled

quicker due to the fewer headers.

Due to the time constraints, there are still cases that require

investigation. Larger data sets could showcase the strength of BSON's

serialization, especially with more complex values. It would require

defining new structures in the code. With a larger scope, the use of

compression algorithms could be checked as they were not included in

this research - chapter 3.3.

Additionally, the developer could measure the time the Java and

TypeScript applications have spent in garbage collection during the

parsing process. The created objects during the benchmarking had to be

removed from the memory to create new ones. That could be solved, by

enabling debugging logs, profiling the code during the benchmark or

using some integration that measures the hidden processes.

It could be beneficial to check the libraries' executions of their

functions. The code profiler would help to understand the operations.

Perhaps object initialization is very costly in Java, where the faster

approach shares its interface with the data instead of putting it into

fields. Since MongoDB's BSON libraries are open source, the author could

create a ticket on a respective GitHub repository to open a discussion

on why it was not possible to instantiate an object using

RawBsonDocument. The conversation would be an opportunity to understand

more experienced developers and their decisions.

Many other binary formats could be checked as a replacement for BSON.

Such as Protocol Buffers or

UBJSON or custom serialization using libraries

like Deku. Considering other

approaches would be beneficial to examine pros and cons of each.

It would be valuable to compare the resource consumption of Rust and

Java servers. One could perform faster but consume much more CPU time or

memory. The results could help future developers in decision-making when

choosing a tech stack.

From the benchmark results, there's a conclusion that Rust has handled

the responses from Java much faster than it did from the Rust provider

instance. The difference could be due to the embedded Tomcat in the

Spring framework.

The author gained knowledge about the importance of serialization and

data transfer. Meaningful research showcased that the popular is not

always the best. Knowledge of other formats could be beneficial in

future projects or professional work.

The biggest accomplishment was learning Rust's basics and other, more

advanced concepts. Rust's ownership system is very innovative, rendering

the software performant and reliable. The compiler helped to find bugs

throughout the project's progress. Given Rust's popularity gain, it is a

noteworthy addition to one's portfolio.

The introduction of TypeScript has given an insight into the

vulnerability of JavaScript's environment. This examination furthered an

understanding of the utilization of the typing system in modern

front-end applications.

The project was a great opportunity to utilize Python's flexibility in

creating quick scripts. The Matplotlib library has broadened the

author's toolkit to generate charts.

Thanks to the experience gained in the Cloud Computing module, it was

easy to create Virtual Machines using the Google Cloud platform. The

machines required manual work to set up the services and an HTTP server.

It has contributed to the developer's knowledge of Linux systems and

cloud infrastructure.

To make the deployment effortless, the author learned how to create

Docker files to build the components and instrument them using

docker-compose. It was a great contribution that will ease the

environment setup in future projects.

Lastly, the author has expanded their ability to use the terminal. The

project was conducted on a Linux-based operating system.

Neovim was used to write the report and code all

the components besides the Java server. The knowledge of key binds and

additional configuration has augmented the developer performance of

moving around projects. The list of applications and tools used can be

found in appendix 13.

No code was reused to create the products of the project.

NumericObject

interface NumericObject {

id: String;

index: number;

numbr: number;

coordinates: Coordinate[];

}

Coordinate

interface Coordinate {

timestamp: number;

latitude: number;

longitude: number;

}

DummyObject

interface DummyObject {

_id: String;

index: number;

guid: String;

isActive: boolean;

balance: number;

picture: String;

age: number;

eyeColor: String;

name: String;

gender: String;

company: String;

email: String;

phone: String;

address: String;

about: String;

registered: String;

latitude: number;

longitude: number;

tags: String[];

friends: DummyFriend[];

greeting: String;

favoriteFruit: String;

}

DummyFriend

interface DummyFriend {

id: number;

name: String;

}

DummyObject with an array of DummyFriend objects.

DummyObject dummyObject = new DummyObject(

"63dcdee3a473b6e562063a35",

0,

"8c514ba0-f517-46ea-9dc3-dfd64c689bcf",

false,

2166.53,

"http://placehold.it/32x32",

29,

"blue",

"JosefaGrant",

"female",

"ZENTIA",

"josefagrant@zentia.com",

"+1(805)529-2872",

"758HubbardStreet,

Roderfield,

Massachusetts,

6249",

"InsitvoluptatedolorLoremnostrudquisLoremauteet.Ametcillumnullacommodoullamcoidelitquiadipisicingfugiatreprehenderitconsequatut.Deseruntsitexcepteurutsuntmagnaesse.Culpanisiquiexcepteurinirureveniamculpatempor.Estipsumdeseruntlaboreesse.Proidentnoneasintincididunttemporeiusmodinnulladolore.\r\n",

"2018-02-17T12:43:54-00:00",

-62.176008,

123.106292,

new String[]{

"minim",

"Lorem",

"ea",

"incididunt",

"voluptate",

"laboris",

"ex"

},

new DummyFriend[]{

new DummyFriend(

0,

"KittyBrock"

),

new DummyFriend(

1,

"MirandaMoody"

),

new DummyFriend(

2,

"GeorgetteSherman"

)

},

"Hello,

JosefaGrant!Youhave10unreadmessages.",

"apple"

);NumericObject with an array of Coordinate objects.

NumericObject numericObject = new NumericObject(

"5ef42a23d-4a77-49c5-be8a-7ced8479f915",

0,

36,

new Coordinate[]{

new Coordinate(

8828480041L,

-71.228786,

-97.911745

),

new Coordinate(

9299061322L,

29.996248,

-1.727763

),

new Coordinate(

9052787749L,

-46.622638,

141.685921

),

new Coordinate(

3491739584L,

-59.283697,

35.835898

),

new Coordinate(

1196235471L,

-59.368215,

-167.022009

),

new Coordinate(

7014816742L,

-35.010705,

-75.416994

),

new Coordinate(

3190810328L,

22.557889,

-108.35877

),

new Coordinate(

1756812663L,

-12.775935,

66.956942

),

new Coordinate(

9237021137L,

60.138851,

-27.953068

),

new Coordinate(

8377575119L,

70.411835,

25.353941

)

});

The server and UI benchmark CSV files and graphs are submitted as an addtional material. The ZIP file is named benchmark-results.zip\

-

OS: Pop!_OS 22.04

-

Neovim (For everything else)

-

IntelliJ IDEA (For Java development)

-

curl

-

ssh

-

scp

-

Postman

-

Google Chrome (benchmarking)

-

LaTeX to write the report

The test was conducted on 14th of March.

########## -- JAVA JSON

Time taken for tests: 152.102 seconds

Requests per second: 6574.54 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 6369.08 [Kbytes/sec] received

########## -- JAVA BSON

Time taken for tests: 152.666 seconds

Requests per second: 6550.23 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 6108.86 [Kbytes/sec] received

########## -- RUST JSON

Time taken for tests: 316.532 seconds

Requests per second: 3159.24 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 2967.96 [Kbytes/sec] received

########## -- RUST BSON

Time taken for tests: 319.982 seconds

Requests per second: 3125.17 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 2823.03 [Kbytes/sec] received

The test was conducted on 15th of March.

########## -- JAVA JSON

Time taken for tests: 129.011 seconds

Requests per second: 7751.26 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 7509.04 [Kbytes/sec] received

########## -- JAVA BSON

Time taken for tests: 151.742 seconds

Requests per second: 6590.14 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 6146.08 [Kbytes/sec] received

########## -- RUST JSON

Time taken for tests: 107.848 seconds

Requests per second: 9272.29 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 8710.88 [Kbytes/sec] received

########## -- RUST BSON

Time taken for tests: 107.921 seconds

Requests per second: 9266.06 [#/sec] (mean)

Transfer rate: 8370.22 [Kbytes/sec] received

![Screenshot of Profile Data Request [@twitter]](https://raw.githubusercontent.com/KaczDev/uni-final-project/main/figures/common_data_twitter.png)