- Description

- What's new

- Installation

- Usage

- Options

- Sublime Text Integration

- Custom configuration

- Known issues

Runs common checks against your files to check for issues according to Liferay's formatting guidelines.

This will scan through HTML(-like) files, JS files, and CSS files and detect many common patterns or issues that violate our source formatting rules, such as:

- Properties being unalphabetized, such as

color: #FFF; border: 1px solid; - Longhand hex codes that can be shorthanded, such as

#FFFFFF - Unneeded units, such as

0pxor0em - Missing integers, in cases such as

opacity: .4; - Lower or mixed case hex codes, such as

#fff - Mixed spaces and tabs

- Comma separated lists that are missing spaces, such as

rgb(0,0,0) - Trailing new lines in nested rules

- Misc. property formatting/spacing

- Attributes that are unalphabetized, such as

<span id="test" class="foo"> - Attribute values that are unalphabetized, such as

<span class="lfr-foo hide">

- Mixed spaces and tabs

- Double quoted strings that should be single quoted

- Stray debugging calls, such as

console.log,console.info, etc - Functions that are improperly formatted, such as

function ( - Function arguments that are improperly formatted, such as

.on('foo', function(event) { - Invalid bracket placement, such as

){or} else { - Properties or methods that are non-alphabetically listed

- Trailing commas in arrays and objects

- Variables that are all defined in one statement

- Variables being passed to

Liferay.Language.get() - Trailing or extraneous newlines

- Variable names starting with

is(it ignores methods, which is valid, but properties and variables should not have a prefix ofis) - Experimental Will try to parse JavaScript inside of aui:script blocks

As of v2, there are a few new features:

- Custom configuration

- Custom configuration on a per file basis or using globs

- New, shorter command:

csf - Now able to check on both ES6+ and JSX syntaxes

- Uses stylelint for CSS checking, which should reduce false positives

- Now requires Node 4+

For any consumers of the API, there was previously no way to know when the CLI object had finished reading the files and reporting the errors, whereas now, cli.init() returns a promise so you can run anything you want to after everything has been processed.

<sudo> npm install -g check-source-formatting

The

check_sfcommand is now deprecated in favor of the newcsfcommand. They're identical (thoughcheck_sfwill periodically warn you that it's deprecated), butcheck_sfwill be removed in the next major version.

The simplest way to run it is:

csf path/to/file

However, you can also check multiple files at once:

find . -name '*.css' | xargs csf

I find it easier to use it with pull requests and check the files that were changed on the branch. In my .gitconfig I have:

sfm = "!f() { git diff --stat --name-only master.. | tr \"\\n\" \"\\0\" | xargs -0 -J{} csf {} $@; }; f"

When someone sends me a pull request, I check out the branch and run git sfm and it scans the changed files and reports any issues.

There are some options that you can pass to the command:

--config If you pass this flag with a path to a configuration file, it will use that one instead of looking up one.

If you pass --no-config, it will disable any custom configuration look ups, and only use the defaults.

-q, --quiet will set it so that it only shows files that have errors. By default it will log out all files and report 'clear' if there are no errors.

-o, --open If you have an editor specified in your gitconfig (under user.editor), this will open all of the files that have errors in your editor.

-i, --inline-edit For some of the errors (mainly the ones that can be safely changed), if you pass this option, it will modify the file and convert the error to a valid value.

-l, --lint If you don't pass anything, --lint defaults to true, which switches on the linting of the JavaScript.

If you pass --no-lint it will overwrite the default and disable linting.

--junit [pathToFile] If you wish to output the results of the scan to a JUnit compatible XML file (useful for allowing integration servers to automate the check and output the results).

If you don't pass the path to the file, it will default to "result.xml".

--filenames Print only the file names of the files that have errors (this option implies --quiet). This is useful if you wish to pipe the list of files to other commands.

--f, --force Formatters can choose to ignore certain files (for example, the JS formatter ignores files that end with -min.js). If you want to force the formatter to run on that file, pass this option.

-r, --relative This will display the files passed in as relative to you current directory.

This is mainly useful when you want to show the file name relative to your current working directory.

I use it mainly when I'm running this on a git branch. In order for it to work from your alias, you would need to change the above alias to be:

sfm = "!f() { export GIT_PWD=\"$GIT_PREFIX\"; git diff --stat --name-only master.. | tr \"\\n\" \"\\0\" | xargs csf $@; }; f"

-v, --verbose This will log out any possible error, even ones that are probably a false positive.

Currently, there's only one testable case of this, which is where you have something like this:

<span class="lfr-foo"><liferay-ui:message key="hello-world" /></span>

This will say there's an error (that the attributes are out of order), but since we can tell there's a >< between the attributes, we know that it's more than likely not a real error.

However, passing -v will show these errors (marked with a **).

--color, --no-color If you don't pass anything, --color defaults to true, which colors the output for the terminal. However, there may be times you need to pass the output of the script to other scripts, and want to have the output in a plain text format.

If you pass --no-color it will overwrite the default and give you plain text.

--lint-ids Previously, all errors that were generated by ESLint or stylelint included their rule ID in the error message. This is no longer true by default (as it adds a lot of noise), but you can turn it on by adding this option.

-m, --check-metadata If we're inside of a portal repository, and one of the files is in the /html/js/liferay/ directory, check all of the modules in that directory, and see if the requires metadata in the files matches the metadata in the modules.js file.

--show-columns If this is passed, it will show the column where the error has taken place. At this time, it only works on JavaScript, since ESLint will give us column information, but I may work something out for this in the future. This one is added mainly for Sublime Linter and other scripts that may wish use the information. It defaults to false, since it's not super useful in regular usage (at least I haven't found it to be).

If you pass -v, it will give you the lines in each file, as well as a merged version (useful for copy/pasting to update the metadata).

--fail-on-errors If this is passed, and any files report errors, this will send a non-zero exit code. This is useful if you're using it from the command line, and wish to halt the execution of any other actions.

If you are using the Node API instead of the CLI, then the results array returned from the Promise will have a property of EXIT_WITH_FAILURE set to true.

Examples of how you might use this (though, probably not often, at least until I have time to distinguish errors from warnings).

CLI

csf some_file_with_errors.css --fail-on-errors && do_some_new_build_task

Node API

var cliInstance = new cli.CLI(

{

args: ['some_file_with_errors.js'],

flags: {

failOnErrors: true

}

}

);

cliInstance.init().then(

function(results) {

console.log(results.EXIT_WITH_FAILURE); // logs out 'true'

}

);There are now two ways you can integrate this module with Sublime Text:

You can setup a build system in Sublime Text to run the formatter on the file you are working in, and this is the simplest of the options. You can set up your build system using the following steps:

- Go to the menu labeled Tools > Build System > New Build System

- Use the following code for the new build system and save the file

{

"shell_cmd": "csf $file"

}

- Go to Tools > Build System and select the system you created

And that's it. When you build the file (Tools > Build) the result will be shown in the Sublime Text command line. You can also install SublimeOnSaveBuild plugin via Package Control to automatically build the file when you save it. Thanks to Carlos Lancha for the idea and docs.

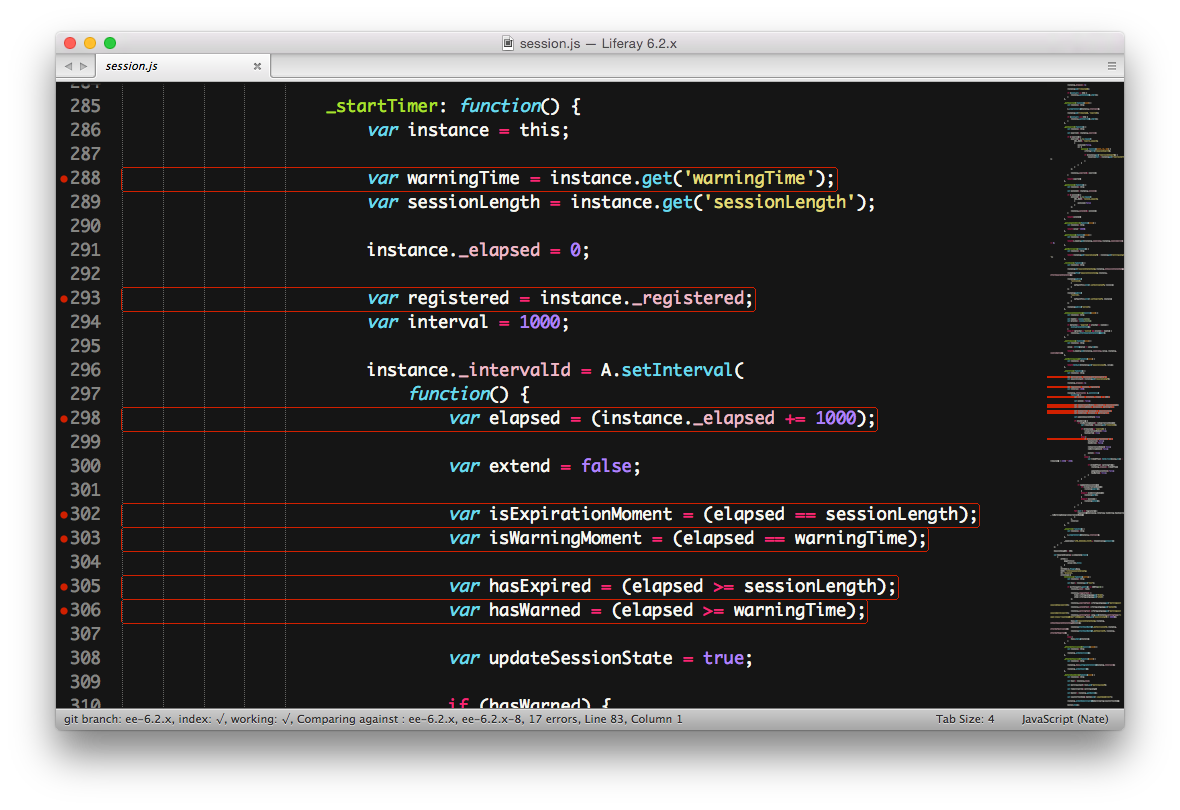

You can also use Sublime Linter to visually see in your code where the errors are:

You can install it via a couple of steps:

- Install Sublime Linter via Package Control

- Install the SublimeLinter-contrib-check-source-formatting package via Package Control

- In order to get it to lint, you may need to either manually lint it (in the Command Palette, type "Lint this view" and select it), or you may wish to change when it lints (in the Command Palette again, type "Choose Lint Mode", and select when you want it to lint the file).

You can read more on the project page. Thanks to Drew Brokke for writing the plugin and publishing it.

- Install liferay-linter via

apm install linter linter-liferay

You can read more on the github page. Thanks to Michael Hadley for writing the plugin and publishing it.

Starting in version 2, you can now customize the configuration of the engine in a few different ways. Here are the items you can currently customize:

- ESLint rules

- stylelint rules

I'm planning on expanding this into more areas, but currently those are the two sections that can be modified.

How do you define a custom configuration?

We are currently using cosmiconfig to look for configuration files, which means you can define custom configuration by adding any one of the following files somewhere in the current working directory or one of the parent directories:

- Inside of

package.json, using a custom key ofcsfConfig csf.config.js.csfrcin JSON or YAML format

What does the structure of the configuration look like?

Let's say we create a .csf.config.js file, our configuration, at the very least, should export a JSON object like so:

module.exports = {};

Here is an example of a config with all keys defined:

module.exports = {

css: {

lint: {}

},

js: {

lint: {}

},

html: {

css: {

lint: {}

},

js: {

lint: {}

}

},

'path:**/*.something.js': {

js: {

lint: {}

}

}

};

(please note, if using one of the JSON files, you'll need to quote the Object keys, however, there are some benefits to using a plain JS file, which I'll mention below).

And here are the descriptions of what they do:

css.lint- These accept any option that can be passed to stylelint, which is really just the rule configuration.

This means anywhere the lint object is called, you can set the rules.lint- These accept any option that can be passed to ESLint, you can set here. This includes any environment or globals you wish to define, rules you wish to define, etc.

This means anywhere the lint object is called, you can set the rules.

Thehtml.css.lintproperty is only applied for style blocks inside of HTML-like files that go through the HTML formatter. This property is merged on top of anything specified incss.lint.

Thehtml.js.lintproperty is only applied for script blocks inside of HTML-like files that go through the HTML formatter. This property is merged on top of anything specified injs.lint.

You'll also notice that a key there of path:**/*.something.js. This allows you to specify a configuration to a specific file path, or a glob referencing a file path.

Any files matching that glob will apply those rules on top of the ones inside of css.lint, js.lint, html.css.lint, and html.js.lint.

As I mentioned before, there are some benefits to using a .js file, but mainly is that it's less strict about what can go inside of the file, so you can use comments, and unquoted keys.

But also, any configuration you define with a function as the value, that function will be executed, and anything you return from there will be used as the value.

This means you can dynamically configure the script at runtime.

You can configure ESLint to leverage specific plugins for your project. The way you would do this is slightly hokey, but it's because ESLint only looks for plugins next to where eslint itself is installed. Because of this limitation, we need a path to the plugin you wish to use.

Here's how you would set it up to use, let's say the Lodash eslint plugin:

- In your project, run the following command:

npm install --save-dev eslint-plugin-lodash

- In your configuration file, add the following:

{

"js": {

"lint": {

"plugins": ["./node_modules/eslint-plugin-lodash"]

}

}

}

- Then, in the same block, you can configure any rules from the plugin by adding a

rulesobject, and configuring it like so:

{

"js": {

"lint": {

"plugins": ["./node_modules/eslint-plugin-lodash"],

"rules": {

"lodash/prefer-noop": 2

}

}

}

}

Right now, it's not possible to use stylelint plugins, but I'll be adding support for that soon. You can still, however, configure the rules included with stylelint.

We include the eslint-plugin-react by default, but we only turn it on for projects that are using JSX syntax (whether it's React or MetalJS), but you need to explicitly opt into ES6 or above in your configuration. We currently handle es7 code, but we don't enable any of the future focused rules such as prefer-template, unless you set your lint.parserOptions.ecmaVersion to 7 in your config file. This is how you would do it:

"lint": {

"parserOptions": {

"ecmaVersion": 7

}

}

Once you have that set, it will enable the react plugin rules for JSX syntax checking, and for upgrading your code to more future focused syntax.

The following are known issues where it will say there's an error, but there's not (or where there should be an error but there's not)

- If you have multiple tags on one line, but separated by spaces, like the following:

<span class="lfr-foo">(<liferay-ui:message key="hello-world" />)</span>

then it will still flag that as an error

- Spaces inside of JS comments will most of the time get flagged as mixed tabs and spaces

- Double quotes inside of JS (like inside of a regex or in a comment), will get flagged as an error.