Code for a project investigating the use of neural encoding models who's representations can nonlinearly to align with those of the neural data being predicted, where the degree of this warping can be controlled by only modifying the model's parameters in a low-dimensional subspace.

Linear encoding models allow us to compare representations while allowing for invariance to linear transformations. While this seems sensible, we might want to permit a certain degree of nonlinear transformations in order to align the representations. Some brain region and a model might learn similar representational manifolds that are nevertheless non-linearly warped relative to each other. For instance, maybe the neural representation maps stimuli to a flat 2d sheet while the model maps them onto a curved 2d sheet; the manifolds are not so dissimilar, but no linear transformation can nicely align them.

At the other extreme, we don’t want to be invariant to arbitrarily complex nonlinear transformations, because then we would be able to align any representations that are highly dissimilar. For instance, we can easily map an image pixel representation to some brain region with a CNN, but it wouldn’t make much sense to say that the pixel representation and the brain are similar.

An interesting alternative might be to allow arbitrary nonlinear transformations, but instead quantifying similarity through predictive performance we can quantify it via the complexity of the transformation. If a model is able to achieve good predictive accuracy with only a simple nonlinear change to its representations, then it makes sense to say that it is a good model of the brain region it was fit to.

This paper developed a method which can be used to modulate the complexity with which we warp a particular representation. Essentially, it allows us to train a model that has many parameters (e.g. a deep neural network), while only modifying these parameters through a low-dimensional parameter subspace. Effectively, there is a random projection from a low-dimensional parameter embedding vector of size

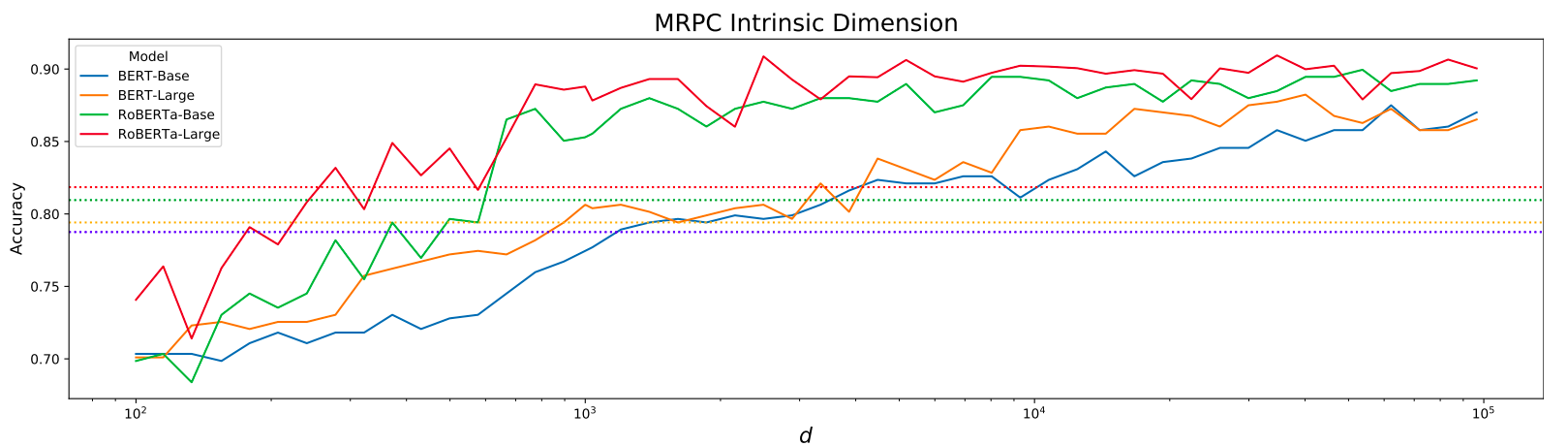

A follow-up paper to the work used this method to compare different models in a transfer-learning setting. Essentially, for different language models fine-tuned on downstream transfer tasks, they compared the

If we want to compare two models, we can see how large

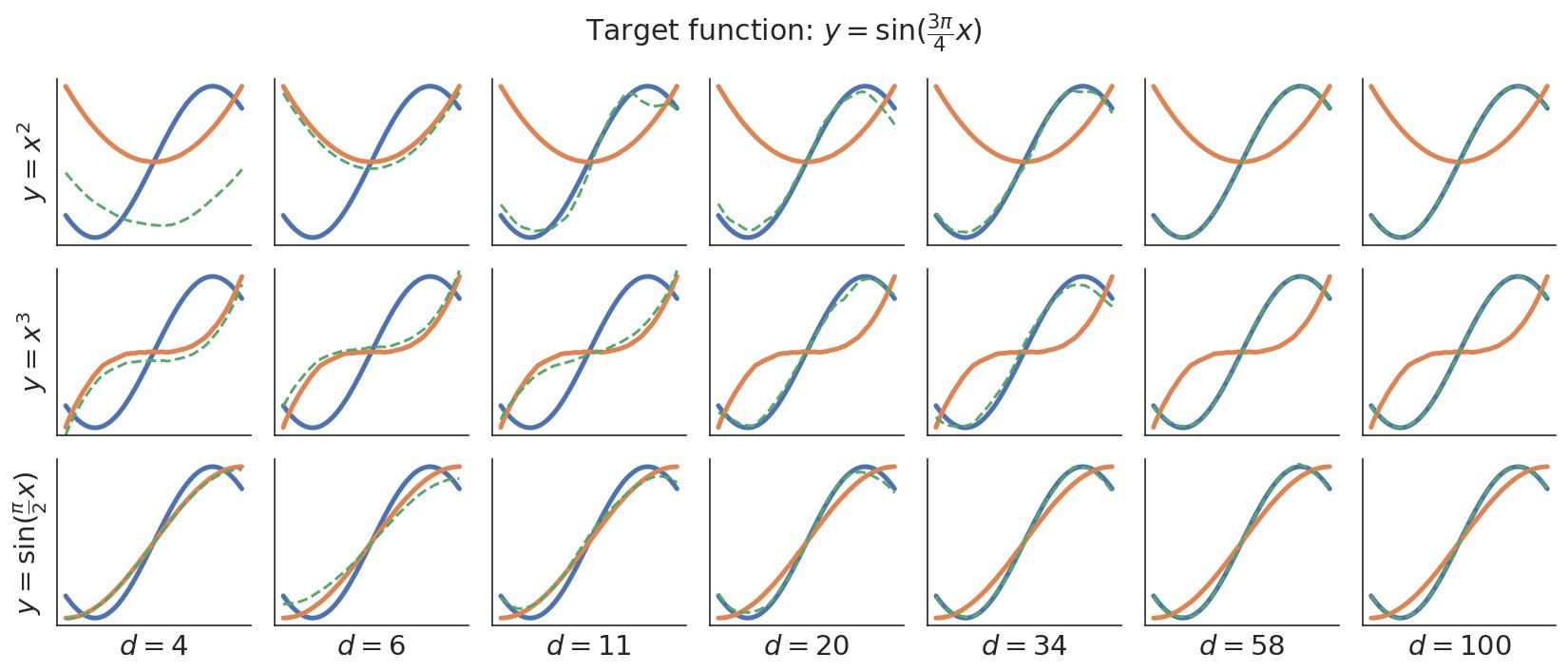

This concept is illustrated in the figure below. Say we have some target representation (the function in blue) and some candidate models (the 3 functions in orange on separate rows). All of these functions using an MLP neural network, so they have lots of parameters. We can fine-tune the candidate models to fit the target representation using increasingly large parameter embedding spaces

Contains the wrapper class for generating a copy of a nn.Module that has a low-dimensional parameter embedding. Any arbitrary PyTorch model can be passed in. You can specify (1) the dimensionality of the parameter embedding and (2) groups of layer names which will have their own learned scaling factors. See the task dimensionality paper for details regarding the Fastfood transform that projects low-dimensional parameters to a high-dimensional space and the layer scaling factors. Importantly, a FastfoodWrapper model's only trainable parameters will be the low-dimensional embedding and the scaling factors.

Definitions for PyTorch models (i.e. nn.Module's) used in experiments. The models should implement the interface specified in models.base.BaseModelLayer, which requires you to specify additional data properties in the model which will be used elsewhere in the code (e.g. the layer you want activations for, the output sizes of each layer, etc.). See models.torchvision_models.ResNet18Layer for an example of a class that implements the BaseModelLayer interface.

When adding new models, make sure to edit the models.__init__.get_model() function so that your model can be retrieved from scripts that train arbitrary encoding models.

Definitions for PyTorch DataPipe's and PyTorch Lightning LightningDataModules's that are used in experiments. The datasets should implement the interface specified in datasets.base.BaseDataModule, which requires you to specify additional data properties in the dataset which will be used elsewhere in the code (e.g. the number of outputs targets, such as voxels). See datasets.nsd.NSDDataModule for an example of a class that implements the BaseDataModule interface.

When adding new datasets, make sure to edit the 'scripts.utils.get_datamodule() function so that your dataset can be retrieved from scripts that train arbitrary encoding models.

Definitions for Pytorch Lightning LightningModule's that are used to train models in experiments.

For standard encoding models where the targets are continuous vectors, the classes defined in tasks.regression should suffice. If for some reason you want to do some very different kind of training, feel free to either extend the functionality of those classes or add new ones to tasks/ folder.

Files in here should contain the code that generates data for any subsequent experiments/figures. The preference is that these scripts should take in argument configurations using the hydra Python library (very simple to use, you can learn it in 10min). The configurations files used by hydra are in scripts/configurations/.

Scripts implemented so far:

-

encoding_dim.py: Fit encoding models through gradient descent using an increasing number of low-dimensional parameter embeddings. The resulting test set performance for all values of$d$ , as well as TensorBoard training curves, will be saved insaved_runs/encoding_dim/[your run name]/results.csv. -

ols_linear_encoder.py: Fit an encoding model through OLS or Ridge regression. This is mainly for quick sanity checks to see what kind of performance you should expect on a given neural dataset, since training with gradient descent can be slow and is sensitive to hyperparameters.

All scripts can be run from the command line as modules:

python -m scripts.[script name] [hydra argument overrides]

Experiments on simulated data to develop theories and intuitions. Each kind of simulation should be in a standalone folder, and can have its own scripts, helper files, notebooks, etc.

Simulations implemented so far:

dim_complexity/: Examples of simple functions being fit to a target function using an increasing number of low-dimensional parameter embeddings.

Unit tests using the pytest library. Please try to add additional unit tests for new code that you write, and re-run existing tests if you change something in the classes/functions that are currently implemented.

The main goal of this study is to compare different models by the

- Different neural datasets (including different ROIs, recording modalities, and species).

- Different model architectures.

- Different layers (e.g. depths).

- Different training tasks.

- Different pre-training datasets (e.g. not just ImageNet).

In particular, we want to see if we learn something new by comparing models according to

So far, I've trained a deep layer of an ImageNet-trained ResNet18 at various levels of scripts/configurations/data/ (some of these paths will be in my local folder, so just ping me if you can't read from them and need me to copy them elsewhere).

The results for these experiments are relatively encouraging. What I was looking for was whether or not higher values of

Really, we want to see how complex a change we need to make to the model before its representations align with those of the brain. Currently, after changing the model's representations by tuning its internal parameters, we still have a linear encoding layer at the end to optimize an actual alignment. This complicates the validity of the method, because that linear layer itself has parameters (the number of which will also depend on how many units are in the model's final representation).

On the one hand, this kind of linear projection might be necessary given issues in the neural data such as limited numbers of stimuli, recordings from a limited number of brain regions, lossy/noisy recording modalities, subjects performing a single fixed task, etc.

Nevertheless, if we want to see something like "how many parameters must change in the model to align it with the neural representations", perhaps we can skip the linear projection entirely and use a sort of RSA objective function to train the low-dimensional parameter embedding. Since RSA can be differentiable, we should be able to write a loss function for it that can be optimized using gradient descent.

Gradient descent methods would still be necessary because there's no other good way to optimize the DNN (i.e. we can't write a closed form solution for the optimal low-dimensional parameters). In addition, if the stimulus set is sufficiently large such that we can't pass it as an entire batch to the model and obtain gradients, we'll need an batched form of this RSA objective (although this might be as simple as just doing RSA on the current batch).

Note that this batched RSA-like objective is similar to some loss functions used in contrastive learning, since it considers the distance between all pairs of samples in the batch, so it's probably a theoretically-sound thing to do.

To eliminate the same concern as above, Raj came up with an alternative idea. First, we can just fine-tune the final linear layer using SGD, or even OLS/Ridge/PLS (since we won't have to backpropagate through the rest of the model). Afterwards, we can consider the initial model + the linear layer as "the model", and fine-tune all of its parameters through the low-dimensional embedding. The linear layer's parameters would be included in the

One of the advantages of this is that it would allow us to fit these linear projections on top of a concatenated vector of model layers. This is something that would not be easy to do with the RSA approach above, because that approach requires us to manually specify a layer-ROI correspondence ourselves.