Project: Image Editor

Project Description and Motivation -

This project is an implementation of an image editor. The motivation behind this project is to improve the compute time taken by image editors. In a digital world, appearances online have become so important, from Zoom meeting filters to liven a call, to Instagram pages to promote products. With the increase in the ubiquity of multi-core machines, parallel computing offers a new paradigm of programming that can take advantage of more compute power to drastically decrease the wait time to produce images that may just brighten someone's day.

In this image editor, images are transformed based on a sequence of effects that are to be applied to each image along with the name of the image to be transformed and the name of the transformed image to be saved. These transformations (effects) are carried by applying specific kernels through a convolution operation over the entire image. For all effects, a 3x3 kernel is convolved over patches (iterating over the entire image).

The editor processes image tasks specified in three different ways i.e. sequential, work stealing (ws) and work balancing (wb) parallel mode. In work balancing, a thread determines whether it needs to balance work with another thread chosen at random. The decision to balance is based on the balance threshold specified as a command-line argument. If the difference in the number of tasks assigned to a thread's queue and another queue chosen at random, is greater than or equal to the balancing threshold, then the thread will balance work with the other chosen thread. In the work stealing algorithm, upon the completion of all tasks assigned to a thread, the thread will steal work from another thread chosen at random (if of course the other thread's queue contains image tasks to be processed).

Important System Components -

-

Data (Input):

-

I/O takes places in the

datadirectory. If there is nodatadirectory, you can create one usingmkdir datawhile inside the project directory. -

Each editor task is provided within the directory

data/effects.txtfile. An example of an editor task is shown below (multiple tasks can be specified by placing one on each line of theeffects.txtfile and are in theJSON format-{"inPath": "IMG_2029.png", "outPath": "IMG_2029_Out.png", "effects": ["G","E","S","B","M"]} -

Input images must be provided within the a directory inside

data/indirectory. If one does not exist, you can create it from withindatausingmkdir in. Similarly for the directory. For example, to process an image, we can createdata/in/smalland place the image inside this directory. -

Input images are provided in the

PNGformat. -

The data can be found here. Make sure to copy the

datafolder into the root directory of this project.

-

-

Data (Output):

-

I/O takes places in the

datadirectory. If there is nodatadirectory, you can create one usingmkdir datawhile inside the project directory. -

After processing images, the transformed images are saved within the

data/outdirectory. If one does not exist, you can create it from from withindatausingmkdir out. -

Processed images are saved in the

PNGformat.

-

-

Effects:

-

The following effects can be applied (the appropriate identifier to be used is specified in parenthesis for each effect) -

-

Grayscale (G) - Each pixel's color channels are computed by averaging over the each the original pixel's color channel values.

-

Sharpen (S) - The following kernel is used as part of the convolution operation applied at every pixel using the convolution operation -

$$ \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -1 & 0\ -1 & 5 & -1\ 0 & -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} $$

-

Blur (B) - The following kernel is used as part of the convolution operation applied at every pixel using the convolution operation -

$$ \frac{1}{9} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1\ 1 & 1 & 1\ 1 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

-

Edge Detection (E) - The following kernel is used as part of the convolution operation applied at every pixel using the convolution operation -

$$ \begin{bmatrix} -1 & -1 & -1\ -1 & 8 & -1\ -1 & -1 & -1 \end{bmatrix} $$

-

Emboss (M) - The following kernel is used as part of the convolution operation applied at every pixel using the convolution operation -

$$ \begin{bmatrix} -1 & -1 & 0\ -1 & 0 & 1\ 0 & 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

-

-

Note that these identifiers for each effect are case sensitive.

-

Convolution is performed on a 2D image grid by convolving the kernel across the image. The convolution operation can be thought of as a sliding window computation over the entire image. The computation being performed is the frobenius inner product which is the sum over element wise products between the kernel and patch of image overlapping with the kernel. Zero padding is used at the edges of the image. The convolution operation can be seen below -

$$y[m,n] = x[m,n] \ast h[m,n] = \sum_{j=-\infty}^{\infty} \sum_{i=-\infty}^{\infty} x[i,j] h[m - i, n - j]$$

-

-

Run Modes: The following modes can be used with the identifier specified in parenthesis (for sequential mode, no mode is specified when running the program).

-

sequential - If no mode is specified, then the sequential version is run.

-

work balancing (wb) - This runs the editor in the parallel work balancing mode, which balances the tasks given to each worker based on the balance threshold specified. The number of threads and the balance threshold must be specified in this mode. Each thread spawned will work on image tasks (including all of the effects for the image task).

-

work stealing (ws) - This runs the editor in the parallel work stealing mode, in which workers steal tasks from other workers if the worker completes all of the tasks distributed to it. The number of threads must be specified in this mode. Each thread spawned will work on image tasks (including all of the effects for the image task).

-

Running the Program -

The editor can be run in the following way -

The first step to run any of the following modes is -

foo@bar:~$ cd editor- Sequential run -

foo@bar:~$ go run editor.go <image directory>-

Parallel runs -

- Work Balancing -

foo@bar:~$ go run editor.go <image directory> wb <number of threads to be spawned> <balancing threshold>- Work Stealing -

foo@bar:~$ go run editor.go <image directory> ws <number of threads to be spawned> -

Multiple Input Image Directories -

If there a images in multiple directories within data/in, for example, if there was the directories small and big, we can chain directories to process using + -

foo@bar:~$ go run editor.go small+big ws <number of threads to be spawned>Benchmarking the Program -

All testing has been carried out on the CS linux cluster i.e. the Peanut Cluster.

Peanut Cluster specifications -

1. Core architecture - Intel x86_64

2. Model name - Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2420 0 @ 1.90GHz

3. Number of threads - 24

4. Operating system - ubuntu

5. OS version - 20.04.4 LTS

The program can be benchmarked using the following command -

foo@bar:~$ sbatch benchmark_editor.shThis must be run within the benchmark directory. Make sure to create the slurm/out directory inside benchmark directory and check the .stdout file for the outputs and the timings.

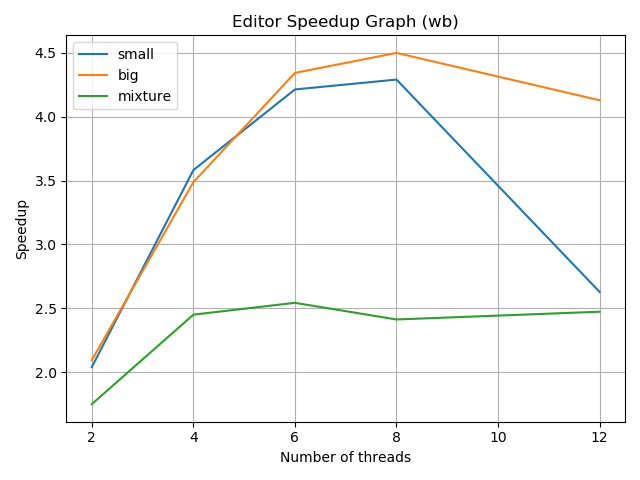

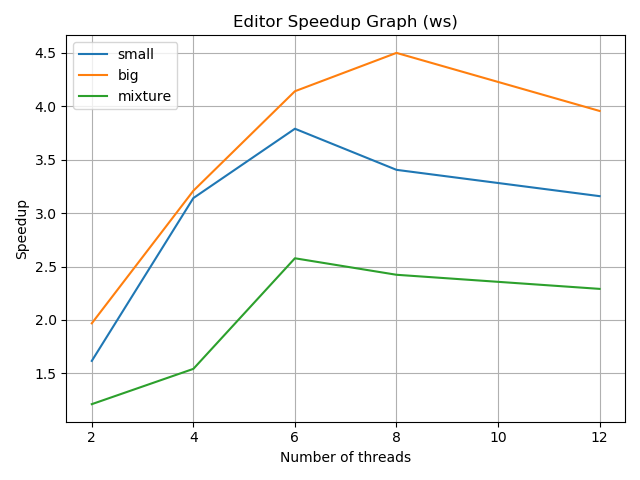

The graph of speedups obtained can be seen below -

The graphs will be created within the benchmark directory. The computation of the speedups along with the storing of each of the benchmarking timings and the plotting of the stored data happens by using benchmark_graph.py which is called from within benchmark_editor.sh (both reside in the benchmark directory).

The following observations can be made from the work balancing mode graph -

-

The speedup is almost linear with the number of threads (up to a point). This is because the work is balanced across the threads and the threads are not waiting for each other to complete their tasks.

-

We see a decrease in speedup as the number of threads increases. This is because the overhead of the communication and synchronization between the threads increases as the number of threads increases.

-

We see greater speedups for the small and big images compared to the mixture dataset. This is because in the case of the mixture dataset, since there are different sizes in images, some tasks will finish a lot faster than other tasks, leaving threads that have no work (in the case that the difference in thread local queue sizes is less than the balance threshold, and therefore, no threads steal).

-

We see greater speedups in the big dataset because the images are larger. This means that the size of the problem amortizes the overhead of the communication and synchronization between the threads (better than in the small image dataset).

The following observations can be made from the work stealing mode graph -

-

Similar to the work balancing mode, we see a close to linear speedup with the number of threads (up to a point). This is because when a thread finishes its tasks, it can steal tasks from other threads. Therefore, the idle time of threads is reduced, and the overall throughput of the application is increased.

-

Once again, we see greater speedups in the big dataset because the images are larger. This means that the size of the problem amortizes the overhead of the communication and synchronization between the threads (better than in the small image dataset).

-

After around 8 threads, we see a decrease in speedup. This is because the overhead of the communication and synchronization between the threads increases as the number of threads increases and we are not able to amortize this cost anymore.

Comparing the two graphs and their parallel implementations, we can observe the following -

-

Work stealing results in greater speedups than work balancing. This is because work stealing reduces the idle time of threads in the case that the threshold to balance in work balancing is too low i.e. the difference in thread local queue sizes is greater than, and therefore, the overall throughput of the application is increased. In my experiments, I tried to keep the threshold as low as possible to see the difference between the two modes. The graphs above are with a balance threshold of 1 which has been hardcoded in the

benchmark/benchmark_graph.pyscript but can be specified via the command line when running theGoprogram. -

We see that after around 8 threads, the speedup decreases in both the work stealing and work balancing modes. This is because the overhead of the communication and synchronization between the threads increases as the number of threads increases and we are not able to amortize this cost anymore. In the work stealing mode, the threads are able to steal tasks from other threads, but this is not enough to offset the overhead of the communication and synchronization between the threads. However, this does decrease the overall idle time of threads in the work stealing mode better than in the work balancing mode. This is why the decrease in speedup in the work stealing mode, is still better than the decrease in speedup in the work balancing mode i.e. after 8 threads, the speedup in the work stealing mode is still greater than the speedup in the work balancing mode despite both have negative speedup i.e slowdown.

Questions About Implementation -

-

Describe the challenges you faced while implementing the system. What aspects of the system might make it difficult to parallelize? In other words, what to you hope to learn by doing this assignment?

One operation that can be parallelized is each element wise product taken between the image and the kernel and summed to compute a new pixel value. While the element wise product can be handled by a mapping function which is parallelizable (and subsequently reduced by a reducer to find sum of element wise products) this would involve spawning a lot of threads which would increase the overhead associated with the communication and synchronization between the threads. This makes it difficult to parallelize the system at this level of granularity. The challenge was deciding the granularity at which to parallelize. Though I learened a lot about the work stealing and work balancing paradigms for parallelism, I feel that the most important thing I learned was how to parallelize a system at the right level of granularity.

-

What are the hotspots (i.e., places where you can parallelize the algorithm) and bottlenecks (i.e., places where there is sequential code that cannot be parallelized) in your sequential program? Were you able to parallelize the hotspots and/or remove the bottlenecks in the parallel version?

The hotspots of the code are (at varying levels of granularity) -

-

The image tasks (including all effects to be applied for an image).

-

The convolution operation over a single image as multiple threads can work on the same effect of on an image.

-

The element wise product between the image and the kernel which can be parallelized as described above (similar to a MapReduce operation) though I suspect that this would leave to negative speedups.

The bottlenecks of the code are -

- The barrier that needs to be in place to ensure that the next effect can be applied to the image only after the previous effect has been applied to the image.

-

-

What limited your speedup? Is it a lack of parallelism? (dependencies) Communication or synchronization overhead? As you try and answer these questions, we strongly prefer that you provide data and measurements to support your conclusions.

Please refer to the inferences made on the graphs above as well as on the comparison between the speedup graphs and the parallel implementations listed above.