Useful examples at the command line.

eg provides examples of common uses of command line tools.

Man pages are great. How does find work, again? man find will tell you, but

you'll have to pore through all the flags and options just to figure out a

basic usage. And what about using tar? Even with the man pages tar is

famously inscrutable without the googling for examples.

No more!

eg will give you useful examples right at the command line. Think of it as a

companion tool for man.

egcomes from exempli gratia, and is pronounced like the letters: "ee gee".

pip install egbrew install eg-examplesClone the repo and create a symlink to eg_exec.py. Make sure the location you

choose for the symlink is on your path:

git clone https://github.com/srsudar/eg ./

ln -s /absolute/path/to/eg-repo/eg_exec.py /usr/local/bin/egNote that the location of

eg_exec.pychanged in version 0.1.x in order to support Python 3 as well as 2. Old symlinks will print a message explaining the change, but you'll have to update your links to point at the new location. Or you can install withpiporbrew.

eg doesn't ship with a binary. Dependencies are very modest and should not

require you to install anything (other than pytest if

you want to run the tests). If you find otherwise, open an issue.

eg <program>

eg takes an argument that is the name of a program for which it contains

examples.

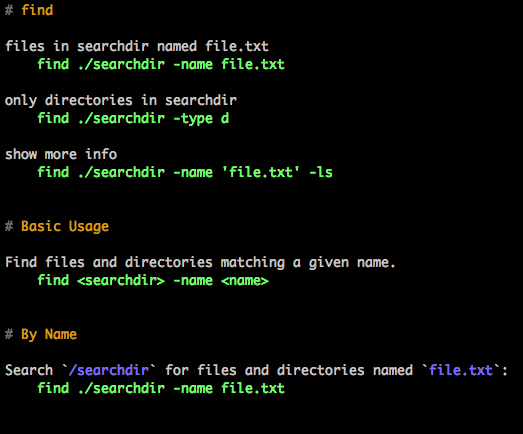

eg find will provide examples for the find command.

eg --list will show all the commands for which eg has examples.

The complete usage statement, as shown by eg --help, is:

eg [-h] [-v] [-f CONFIG_FILE] [-e EXAMPLES_DIR] [-c CUSTOM_DIR] [-p PAGER_CMD]

[-l] [--color] [-s] [--no-color] [program]

Files full of examples live in examples/. A naming convention is followed

such that the file is the name of the tool with .md. E.g. the examples for

find are in find.md.

eg find will pipe the contents of find.md through less (although it tries

to respect the PAGER environment variable).

eg works out of the box, no configuration required.

If you want to get fancy, however, eg can be fancy.

For example, maybe a team member always sends you bzipped tarballs and you can

never remember the flag for bzipping--why can't that guy just use gzip

like everybody else? You can create an example for untarring and unzipping

bzipped tarballs, stick it in a file called tar.md, and tell eg where to

find it.

The way to think about what eg does is that it takes a program name, for

example find, and looks for files named find.md in the default and custom

directories (including subdirectories). If it finds them, it pipes them through

less, with the custom files at the top. Easy.

The default and custom directories can be specified at the command line like so:

eg --examples-dir='the/default/dir' --custom-dir='my/fancy/dir' findInstead of doing this every time, you can define a configuration file. By

default it is expected to live in ~/.egrc. It must begin with a section

called eg-config and can contain two keys: custom-dir and examples-dir.

Here is an example of a valid config file:

[eg-config]

examples-dir = ~/examples-dir

custom-dir = ~/my/fancy/custom/dir

Although by default the file is looked for at ~/.egrc, you can also specify a

different location at the command line like so:

eg --config-file=myfile findIf you want to edit one of your custom examples, you can edit the file directly

or you can just use the -e or --edit flag.

To edit your find examples, for example, you could say:

eg -e findThis will dump you into an editor. The contents will be piped before the default

examples the next time you run eg find.

eg is highly customizable when it comes to output. You have three ways to try

and customize what is piped out the pager, applied in this order:

- Color

- Squeezing out excess blank lines

- Regex-based substitutions

eg is colorful. The default colors were chosen to be pretty-ish while boring

enough to not create problems for basic terminals. If you want to override

these colors, you can do so in the egrc in a color section.

Things that can be colored are:

pound: pound sign before headingsheading: the text of headingscode: anything indented four spaces other than a leading$prompt: a$that is indented four spacesbackticks: anything between two backticks

Values passed to these options must be string literals. This allows escape characters to be inserted as needed. An egrc with heading text a nice burnt orange might look like this:

[eg-config]

custom-dir = ~/my/fancy/custom/dir

[color]

heading = '\x1b[38;5;172m'

To remove color altogether, for example if the color formatting is messing up

your output somehow, you can either pass the --no-color flag to eg, or you

can add an option to your egrc under the eg-config section like so:

[eg-config]

color = false

The example files use a lot of blank lines to try and be readable at a glance. Not everyone likes this many blank lines. If you hate all duplicate lines, you can use your favorite pager to remove all duplicate commands, like:

eg --pager-cmd 'less -sR' find

This will use less -sR to page, which will format color correctly (-R) and

remove all duplicate blank lines (-s).

eg also provides its own custom squeezed output format, removing all blank

lines within a single example and only putting duplicate blank lines between

sections. This can be configured at the command line with --squeeze or in

the egrc with the squeeze option, like:

[eg-config]

squeeze = true

Running eg --squeeze find removes excess newlines like so:

Additional changes to the output can be accomplished with regular expressions

and the egrc. Patterns and replacements are applied using Python's re module,

so look to the documentation for

specifics. Substitutions should be specified in the egrc as a list with the

syntax: [pattern, replacement, compile_as_multiline]. If

compile_as_multiline is absent or False, the pattern will not be compiled

as multiline, which affects the syntax expected by re. The re.sub method is

called with the compiled pattern and replacement.

Substitutions must be named and must be in the [substitution] section of the

egrc. For example, this would remove all the four-space indents beginning

lines:

[substitution]

remove-indents = ['^ ', '', True]

This powerful feature can be used to perform complex transformations, including

support additional coloring of output beyond what is supported natively by

eg. If you wish there was an option to remove or add blank lines, color

something new, remove section symbols, etc, this is a good place to start.

If multiple substitutions are present, they are sorted by alphabetically by name before being applied.

By default, eg pages using less -RMFXK. The -R switch tells less to

interpret ANSI escape sequences like color rather than showing them raw. -M

tells it to show line number information in the bottom of the screen. -F to

automatically quit if the entire example fits on the screen. -X tells it not

to clear the screen. Finally, -K makes less exit in response to Ctrl-C.

You can specify a different pager using the --pager-cmd option at the command

line or the pager-cmd option in the egrc. If specified in the egrc, the value

must be a string literal. For example, this egrc would use cat to page:

[eg-config]

pager-cmd = 'cat'

pydoc.pager() does a lot of friendly error checking, so it might still be

useful in some situations. If you want to use pydoc.pager() to page, you can

pass the pydoc.pager as the pager-cmd.

Example documents are written in markdown. Documents in markdown are easily read at the command line as well as online. They all follow the same basic format.

This section explains the format so that you better understand how to quickly grok the examples.

Contributors should also pay close attention to these guidelines to keep examples consistent.

Anything indented four spaces or surrounded by backticks `like this` are

meant to be input or output at the command line. A single line indented four

spaces is a user-entered command. If a block is indented four spaces, only the

lines beginning with $ are user-entered--anything else is output.

The first section heading should be simply the name of the tool. It should be

followed by the most rudimentary examples. Users that are familiar with the

command but just forget the precise syntax should be able to see what they need

without scrolling. Example commands should be as real-world as possible, with

file names and arguments as illustrative as possible. Examples for the cp

command, for instance, might be:

cp original.txt copy.txt

Here the .txt extensions indicate that these are file names, while the names

themselves make clear which is the already existing file and which will be the

newly created copy.

This section shouldn't show output and should not include the $ to indicate

that we are at the command line.

This section should be a quick glance for users that know what the tool does, know a basic usage is what they are trying to do, and are just looking for a reminder.

Next a Basic Usage section explains the most basic usage without using real

file names. This section gives users that might not know the usual syntax a

more abstract example than the first section. It is intended to provide a more

useful explanation than the first entry in the man page, which typically shows

all possible flags and arguments in a way that is not immediately obvious to

new users of the command. The SYNOPSIS section of the man page for cp, for

example, shows:

cp [-R [-H | -L | -P]] [-fi | -n] [-apvX] source_file ... target_directory

The Basic Usage is intended to provide less verbose, more immediately practical versions of the man page's SYNOPSIS section.

Commands and flags that will affect the behavior are shown as would be entered

in the command line, while user-entered filenames and arguments that do not

alter the command's behaviors are shown in < >. Examples in the Basic Usage

section for the cp command, for instance, might be:

cp -R <original_directory> <copied_directory>

In this command the cp -R indicate the command and behavior and thus are not

given in < >. Case-dependent components of the command, in this case the

directory to be copied and the name of the copy, are surrounded with < >.

Each is wrapped in separate < > to make clear that it is in fact two

distinct arguments.

Subsequent subsections can be added for common uses of the tools, as appropriate.

Although markdown is readable, it can still be tricky without syntax highlighting. We use spacing to help the eye.

-

All code snippets are followed by at two blank lines, unless overruled by 2.

-

Each line beginning a section (i.e. the first character on the line is

#) should be preceded by exactly three lines. -

Files should end with two blank lines.

-

Lines should not exceed 80 characters, unless to accommodate a necessarily long command or long output.

Additions of new tools and new or more useful examples are welcome. eg should

be something that people want to have on their machines. If it has a man page,

it should be included in eg.

Please read the Format of Examples section and review existing example files to

get a feel for how eg pages should be structured.

If you find yourself turning to the internet for the same command again and again, consider adding it to the examples.

eg examples do not intend to replace man pages! man is useful in its own

right. eg should provide quick examples in practice. Do not list all the

flags for the sake of listing them. Assume that users will have man

available.

eg depends only on standard libraries and Python 2.x/3.x, so building should

be a simple matter of cloning the repo and running the executable eg/eg.py.

eg uses pytest for testing, so you'll have to have it installed to run tests.

Once you have it, run py.test from the root directory of the repo.

Tests should always be expected to pass. If they fail, please open an issue,

even if only so that we can better elucidate eg's dependencies.

Alias eg to woman for something that is like man but a little more

practical:

$ alias woman=eg

$ man find

$ woman find