Circuits.GPIO lets you control or read from GPIOs on Nerves or other Linux-based

devices.

This is the v1 maintenance branch. This is the version you want for production use now. To follow v2.0 development, see the circuits_gpio v2.0 branch

If you're coming from Elixir/ALE, check out our porting guide.

Circuits.GPIO works great with LEDs, buttons, many kinds of sensors, and

simple control of motors. In general, if a device requires high speed

transactions or has hard real-time constraints in its interactions, this is not

the right library. For those devices, see if there's a Linux kernel driver.

If you're natively compiling circuits_gpio on a Raspberry Pi or using Nerves,

everything should work like any other Elixir library. Normally, you would

include circuits_gpio as a dependency in your mix.exs like this:

def deps do

[{:circuits_gpio, "~> 1.0"}]

endOne common error on Raspbian is that the Erlang headers are missing (ie.h),

you may need to install erlang with apt-get install erlang-dev or build Erlang

from source per instructions here.

Circuits.GPIO only supports simple uses of the GPIO interface in Linux, but

you can still do quite a bit. The following examples were tested on a Raspberry

Pi that was connected to an Erlang Embedded Demo

Board. There's nothing special about

either the demo board or the Raspberry Pi, so these should work similarly on

other embedded Linux platforms.

A General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) is just a wire that you can use as an input or an output. It can only be one of two values, 0 or 1. A 1 corresponds to a logic high voltage like 3.3 V and a 0 corresponds to 0 V. The actual voltage depends on the hardware.

Here's an example of turning an LED on or off:

To turn on the LED that's connected to the net (or wire) labeled GPIO18, run

the following:

iex> {:ok, gpio} = Circuits.GPIO.open(18, :output)

{:ok, #Reference<...>}

iex> Circuits.GPIO.write(gpio, 1)

:ok

iex> Circuits.GPIO.close(gpio)

:okNote that the call to Circuits.GPIO.close/1 is not necessary, as the garbage

collector will free up any unreferenced GPIOs. It can be used to explicitly

de-allocate connections you know you will not need anymore.

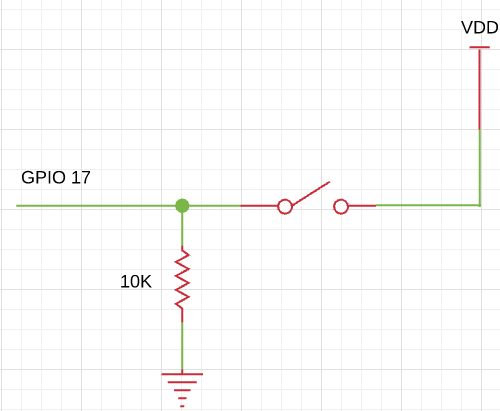

Input works similarly. Here's an example of a button with a pull down resistor connected.

If you're not familiar with pull up or pull down resistors, they're resistors whose purpose is to drive a wire high or low when the button isn't pressed. In this case, it drives the wire low. Many processors have ways of configuring internal resistors to accomplish the same effect without needing to add an external resistor. If you're using a Raspberry Pi, you can use the built-in pull-up/pull-down resistors.

The code looks like this in Circuits.GPIO:

iex> {:ok, gpio} = Circuits.GPIO.open(17, :input)

{:ok, #Reference<...>}

iex> Circuits.GPIO.read(gpio)

0

# Push the button down

iex> Circuits.GPIO.read(gpio)

1If you'd like to get a message when the button is pressed or released, call the

set_interrupts function. You can trigger on the :rising edge, :falling edge

or :both.

iex> Circuits.GPIO.set_interrupts(gpio, :both)

:ok

iex> flush

{:circuits_gpio, 17, 1233456, 1}

{:circuits_gpio, 17, 1234567, 0}

:okNote that after calling set_interrupts, the calling process will receive an

initial message with the state of the pin. This prevents the race condition

between getting the initial state of the pin and turning on interrupts. Without

it, you could get the state of the pin, it could change states, and then you

could start waiting on it for interrupts. If that happened, you would be out of

sync.

To connect or disconnect an internal pull-up or pull-down resistor to a GPIO

pin, call the set_pull_mode function.

iex> Circuits.GPIO.set_pull_mode(gpio, pull_mode)

:okValid pull_mode values are :none :pullup, or :pulldown

Note that set_pull_mode is platform dependent, and currently only works for

Raspberry Pi hardware. Calls to set_pull_mode on other platforms will have no

effect. The internal pull-up resistor value is between 50K and 65K, and the

pull-down is between 50K and 60K. It is not possible to read back the current

Pull-up/down settings, and GPIO pull-up pull-down resistor connections are

maintained, even when the CPU is powered down.

To get the GPIO pin number for a gpio reference, call the pin function.

iex> Circuits.GPIO.pin(gpio)

17Circuits.GPIO supports a "stub" hardware abstraction layer on platforms

without GPIO support and when MIX_ENV=test. The stub allows for some

limited unit testing without real hardware.

To use it, first check that you're using the "stub" HAL:

iex> Circuits.GPIO.info

%{name: :stub, pins_open: 0}The stub HAL has 64 GPIOs. Each pair of GPIOs is connected. For example, GPIO 0 is connected to GPIO 1. If you open GPIO 0 as an output and GPIO 1 as an input, you can write to GPIO 0 and see the result on GPIO 1. Here's an example:

iex> {:ok, gpio0} = Circuits.GPIO.open(0, :output)

{:ok, #Reference<0.801050056.3201171470.249048>}

iex> {:ok, gpio1} = Circuits.GPIO.open(1, :input)

{:ok, #Reference<0.801050056.3201171470.249052>}

iex> Circuits.GPIO.read(gpio1)

0

iex> Circuits.GPIO.write(gpio0, 1)

:ok

iex> Circuits.GPIO.read(gpio1)

1The stub HAL is fairly limited, but it does support interrupts.

If Circuits.GPIO is used as a dependency the stub may not be present. To

manually enable it, set CIRCUITS_MIX_ENV to test and rebuild

circuits_gpio.

Circuits.GPIO is almost Elixir/ALE 2.0. The API for Elixir/ALE became

difficult to change so we started again with Circuits.GPIO. The main

improvements are:

- Improved performance and lower resource usage

- Timestamps on interrupts

- A hardware abstraction layer to support multiple ways of interfacing with the low level GPIO interfaces

See the Porting Guide for more information if you're an Elixir/ALE user.

Most issues people have are on how to communicate with hardware for the first

time. Since Circuits.GPIO is a thin wrapper on the Linux sys class interface,

you may find help by searching for similar issues when using Python or C.

For help specifically with Circuits.GPIO, you may also find help on the nerves

channel on the elixir-lang Slack. Many

Nerves users also use Circuits.GPIO.

Please don't do that - there are so many better ways of accomplishing whatever you're trying to do:

- If you're trying to drive a servo or dim an LED, look into PWM. Many platforms have PWM hardware and you won't tax your CPU at all. If your platform is missing a PWM, several chips are available that take I2C commands to drive a PWM output.

- If you need to implement a wire level protocol to talk to a device, look for a Linux kernel driver. It may just be a matter of loading the right kernel module.

- If you want a blinking LED to indicate status,

gpioreally should be fast enough to do that, but check out Linux's LED class interface. Linux can flash LEDs, trigger off events and more. See nerves_leds.

If you're still intent on optimizing GPIO access, you may be interested in gpio_twiddler.

See whether the "stub" HAL (described above) works for you or could be improved to support your use case.

The following advice from Elixir/ALE may also be useful: You'll need to fake out the hardware. Code to do this depends on what your hardware actually does, but here's one example:

All original source code in this project is licensed under Apache-2.0.

Additionally, this project follows the REUSE recommendations and labels so that licensing and copyright are clear at the file level.

Exceptions to Apache-2.0 licensing are:

- Configuration and data files are licensed under CC0-1.0

- Documentation files are CC-BY-4.0

- Erlang Embedded board images are Solderpad Hardware License v0.51.