RabbitMQ is an open-source message broker software that is widely used for building scalable and robust messaging applications. It is based on the Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) and is written in Erlang, a programming language known for its reliability and fault tolerance. RabbitMQ facilitates the exchange of data between different parts of an application, often in a distributed and asynchronous manner. Here are some key aspects of RabbitMQ in detail:

Message Broker: RabbitMQ acts as a middleman or broker between producers (applications that send messages) and consumers (applications that receive messages). It stores, routes, and delivers messages from producers to consumers based on predefined rules.

Queues: Messages in RabbitMQ are placed in queues. Queues act as temporary storage for messages until they are consumed by consumers. Queues follow a first-in-first-out (FIFO) pattern, meaning the first message added to a queue is the first one to be consumed.

Exchanges: Exchanges are responsible for routing messages from producers to queues. RabbitMQ supports several types of exchanges, including direct, topic, fanout, and headers. The choice of exchange type depends on how messages should be routed.

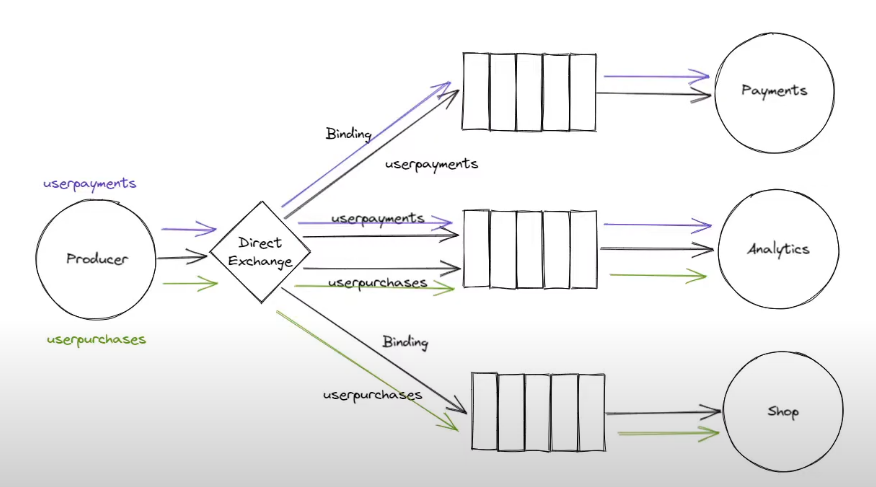

Direct Exchange: Routes messages to queues based on a routing key, which must exactly match the binding key specified by the consumer.

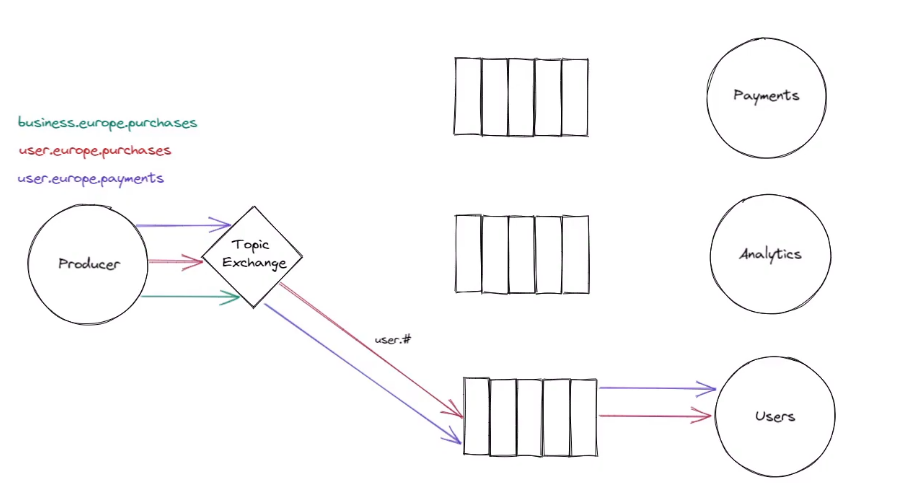

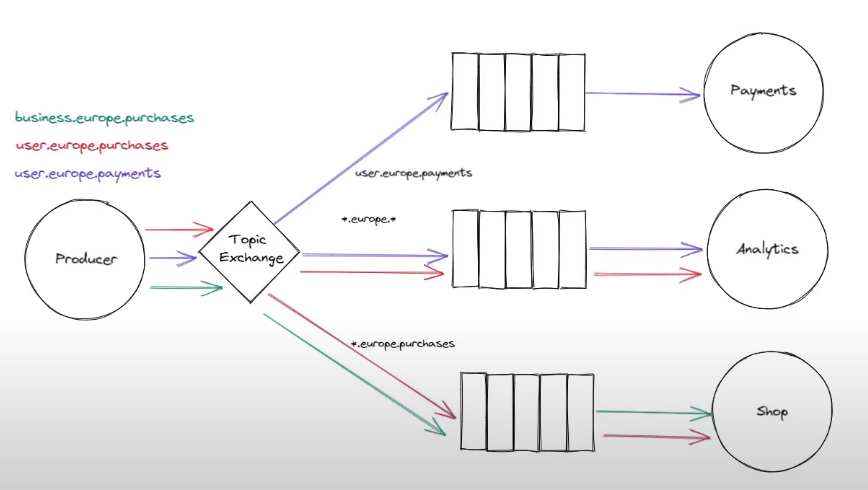

Topic Exchange: Routes messages to queues based on wildcard patterns in the routing key. This allows for more flexible routing.

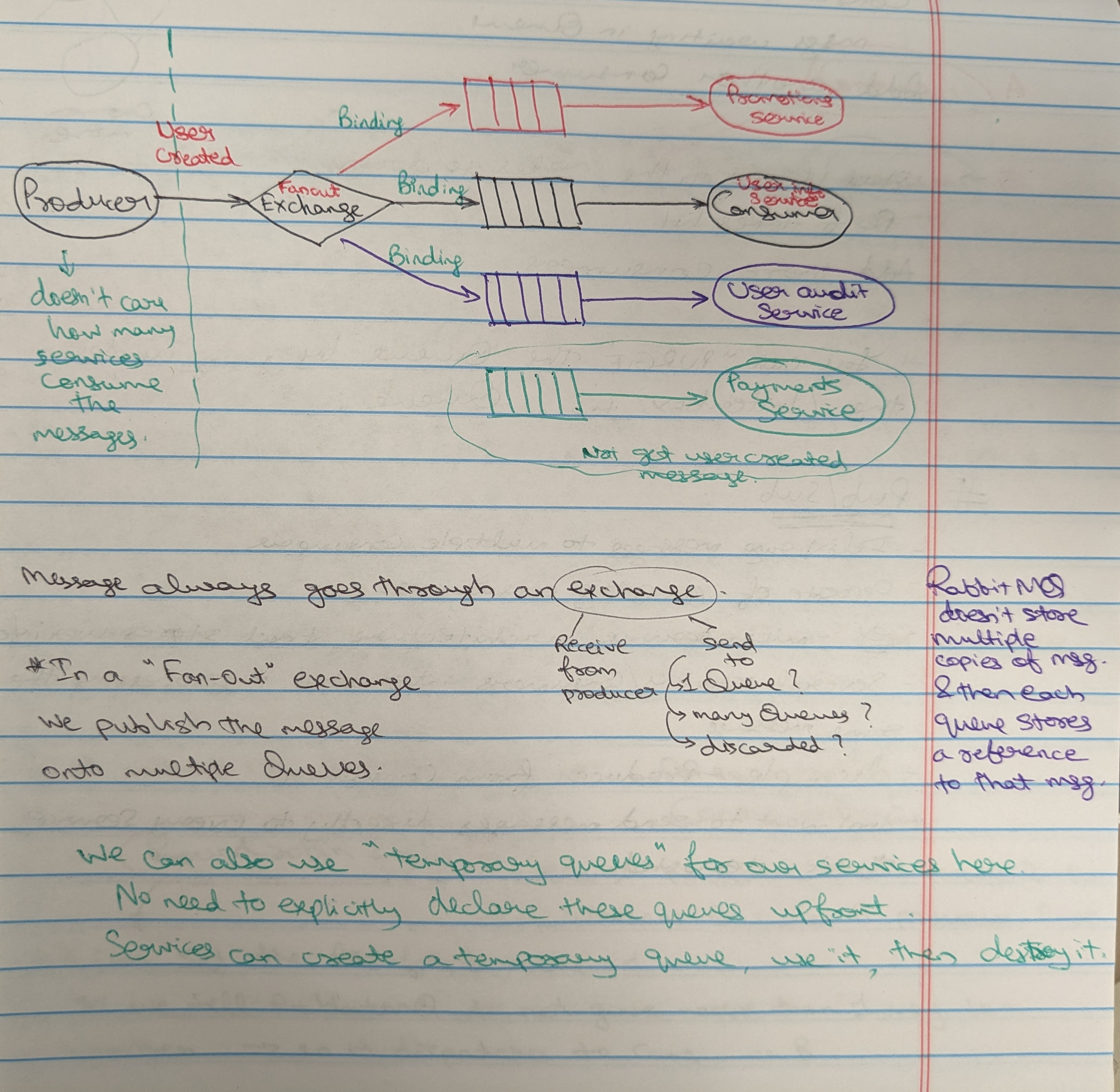

Fanout Exchange: Forwards messages to all queues bound to the exchange, regardless of routing keys. This is useful for broadcasting messages to multiple consumers.

Headers Exchange: Routes messages based on header attributes rather than routing keys.

Bindings: Bindings are rules that connect exchanges to queues, defining how messages are routed. Producers send messages to exchanges, and exchanges use bindings to determine which queues should receive the messages.

Publish/Subscribe: RabbitMQ supports the publish/subscribe messaging pattern through fanout exchanges. In this pattern, a message published to a fanout exchange is delivered to all queues bound to that exchange, making it easy to broadcast messages to multiple consumers.

Message Acknowledgment: Consumers acknowledge the receipt of messages from RabbitMQ. This acknowledgment mechanism ensures that messages are not lost in transit. If a message is not acknowledged, RabbitMQ can re-queue it or move it to a dead-letter queue, depending on the configuration.

Message Durability: RabbitMQ allows you to mark messages and queues as durable. Durable messages and queues are persisted to disk, ensuring that they are not lost in case of a server restart or failure.

Clustering: RabbitMQ can be configured in a clustered setup to enhance reliability and scalability. Clustering enables multiple RabbitMQ nodes to work together as a single logical broker, sharing queues and messages across nodes.

Plugins: RabbitMQ has a plugin system that allows you to extend its functionality. You can add plugins to enable features like message transformation, authentication, and authorization.

Management and Monitoring: RabbitMQ provides a web-based management interface called the RabbitMQ Management Plugin. It offers tools for monitoring and managing RabbitMQ instances, including queue inspection, user management, and message tracing.

Language Support: RabbitMQ client libraries are available for various programming languages, including Java, Python, Ruby, .NET, and more, making it easy to integrate RabbitMQ into applications written in different languages.

Think of email servers as the postal service for the digital world. Just like the postal service handles the sending, receiving, and distribution of physical mail, email servers handle the sending, receiving, and routing of digital messages.

Sending Mail: When you compose an email, it's similar to writing a letter. Your email client (e.g., Gmail, Outlook) acts like your personal mailbox. When you click "Send," your email client sends the message to the email server, which is like the local post office.

Receiving Mail: When someone sends you an email, it's like them dropping a letter in a mailbox. The email server collects and stores incoming emails for you, just as the post office collects and stores physical mail in your mailbox.

Routing and Delivery: Email servers determine where to send your email based on the recipient's address, much like the postal service routes physical mail to the right destination. If the recipient uses a different email provider (e.g., from Gmail to Yahoo), it's like sending a letter from one city to another.

Inbox and Spam: Your email server manages your inbox, where important emails go, and your spam folder, where unsolicited or potentially harmful emails are filtered out. It's similar to how the postal service sorts mail into your mailbox and throws junk mail into the trash.

Attachments: Just as you can include physical documents in an envelope, you can attach files to an email. These attachments are like sending documents with your letter.

A post office serves as the central hub for the distribution of physical mail. Here's how it relates to various aspects of a post office:

Sending Letters: When you want to send a letter or package, you drop it into a mailbox. The post office collects these items, sorts them, and sends them to their respective destinations, just as email servers route emails to recipients.

Mailboxes: Your personal mailbox is like your email inbox. It's where mail is delivered to you. The post office ensures that mail reaches the correct mailbox, similar to how email servers deliver emails to the right recipients.

Mail Sorting: At the post office, mail is sorted based on addresses and postal codes. Similarly, email servers use recipient addresses to determine where to deliver emails.

Delivery Routes: Postal workers follow specific routes to deliver mail to individual houses. In the digital realm, email servers follow data routes to deliver messages to recipients' email clients.

Express Services: Some post offices offer express or priority services for faster delivery. In email, you can mark an email as "urgent" or use priority flags for quicker attention.

Return to Sender: If a letter cannot be delivered (e.g., wrong address), it's returned to the sender. Similarly, undeliverable emails can bounce back to the sender.

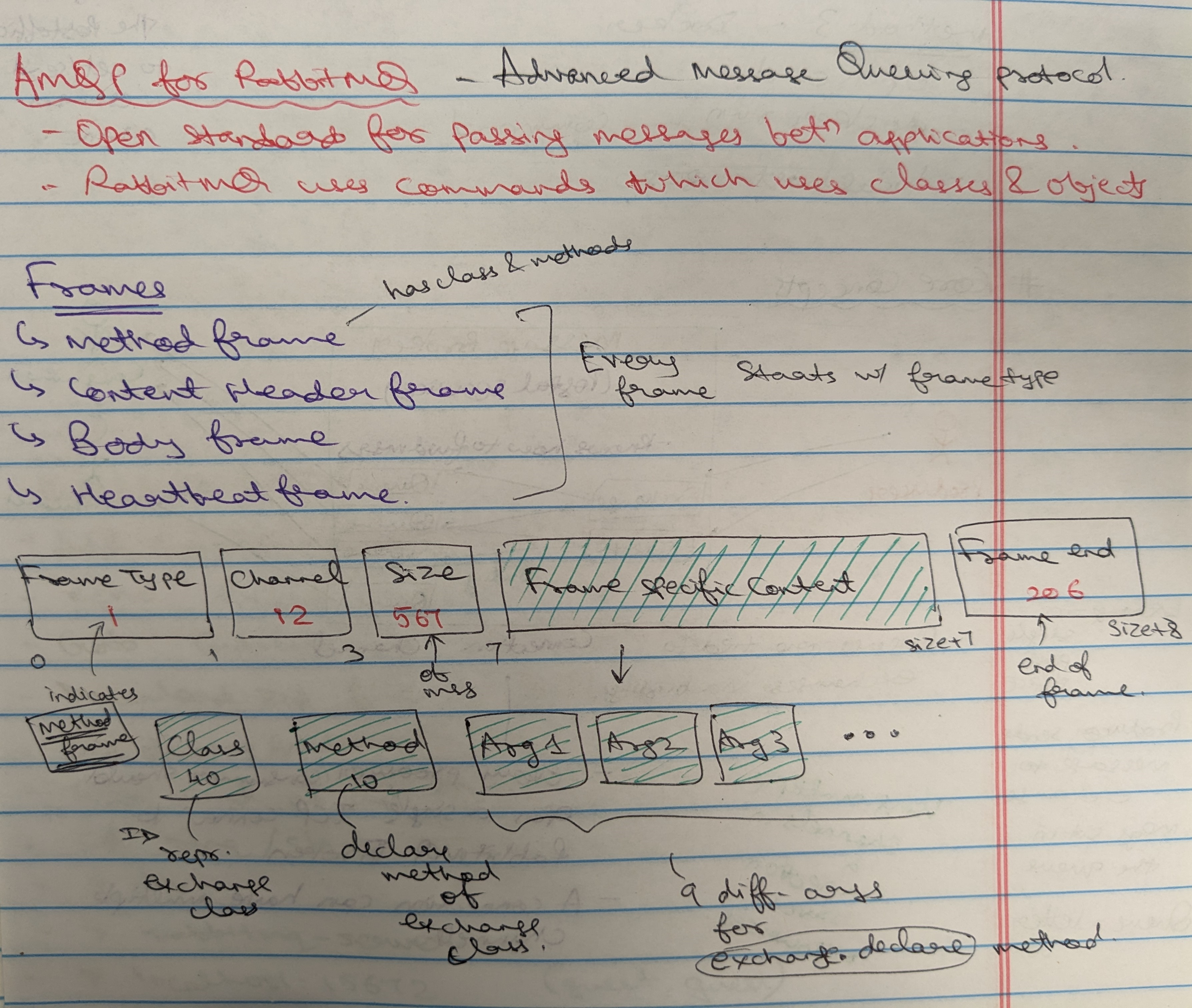

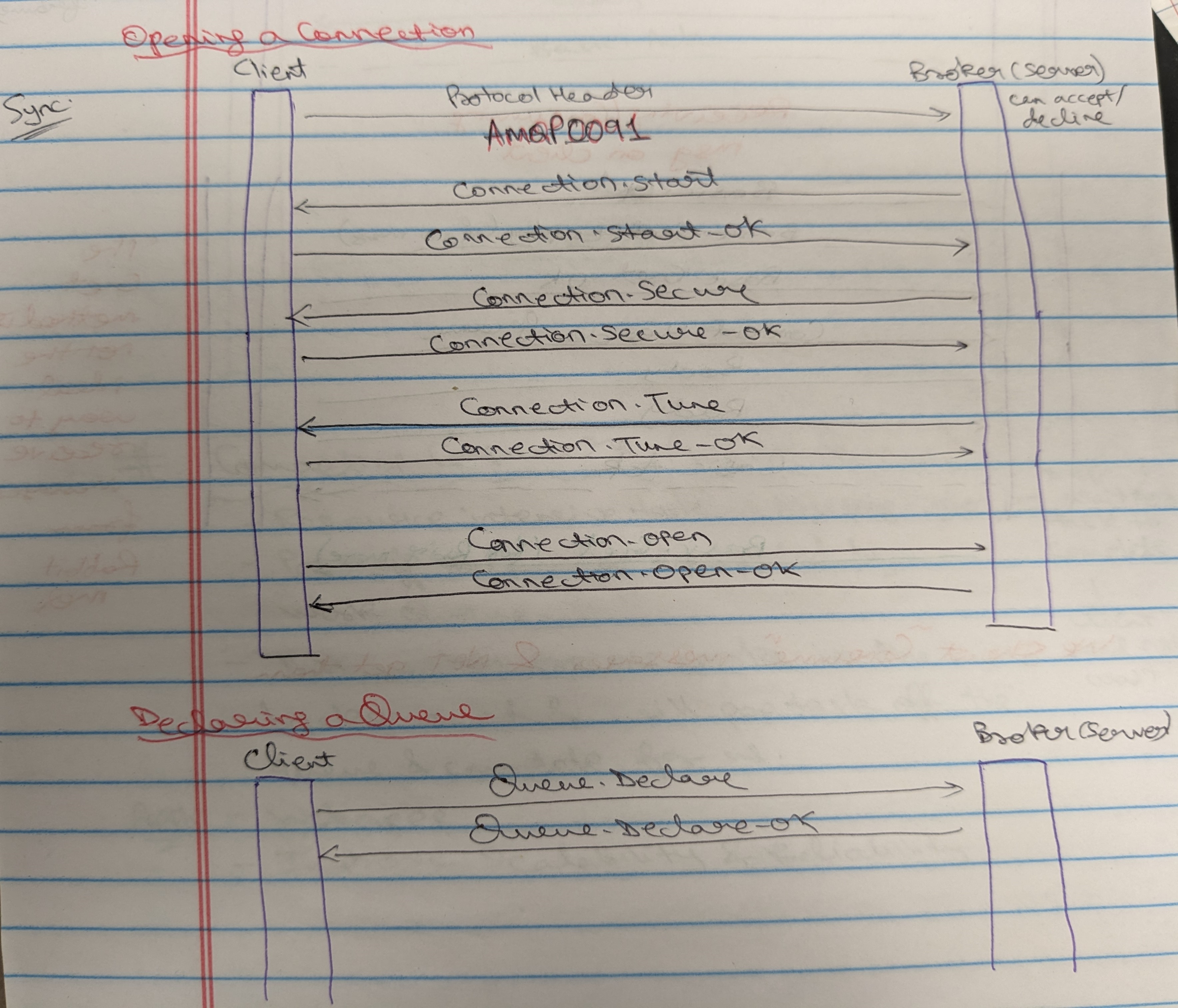

Advanced Message Queuing Protocol

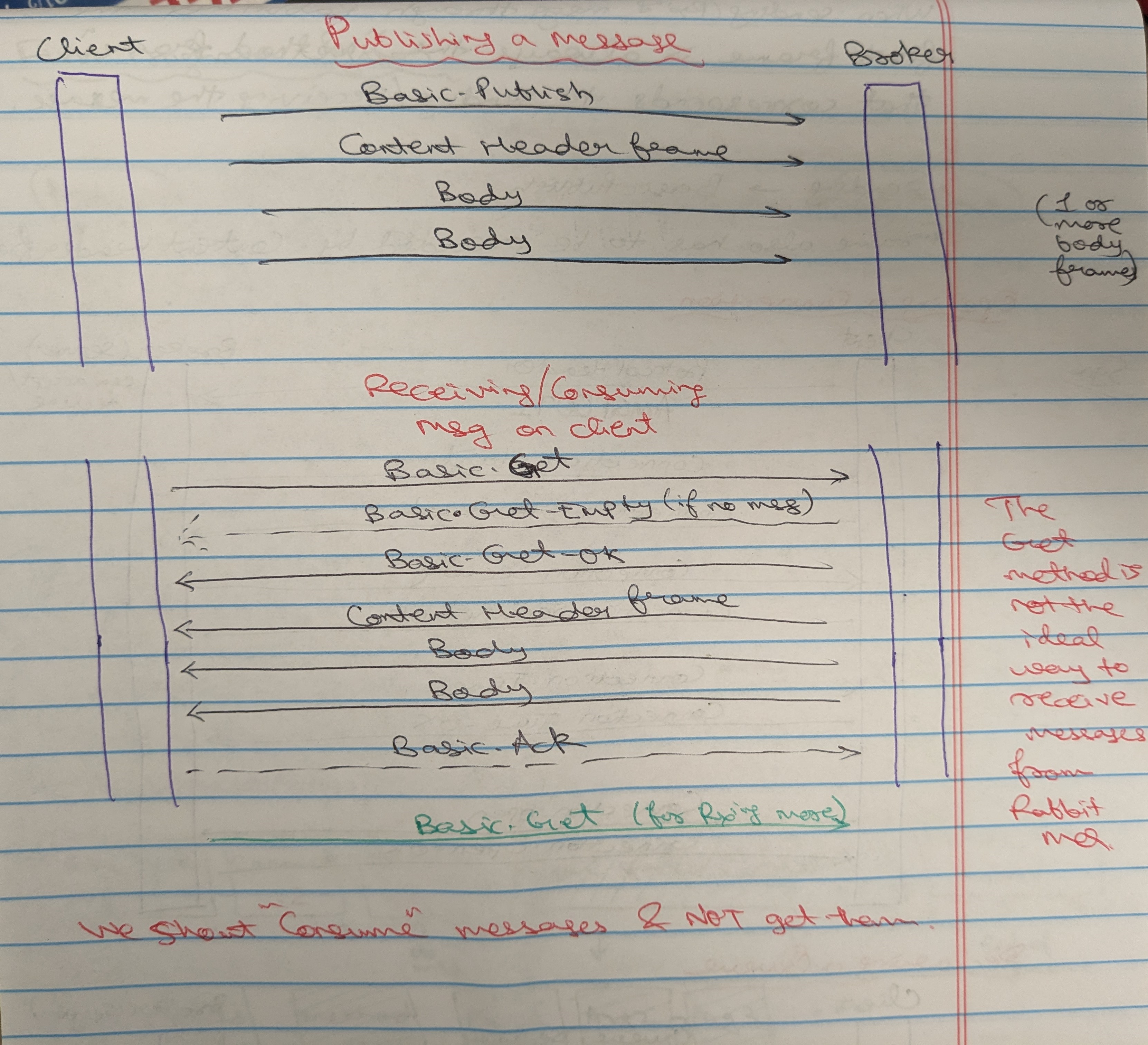

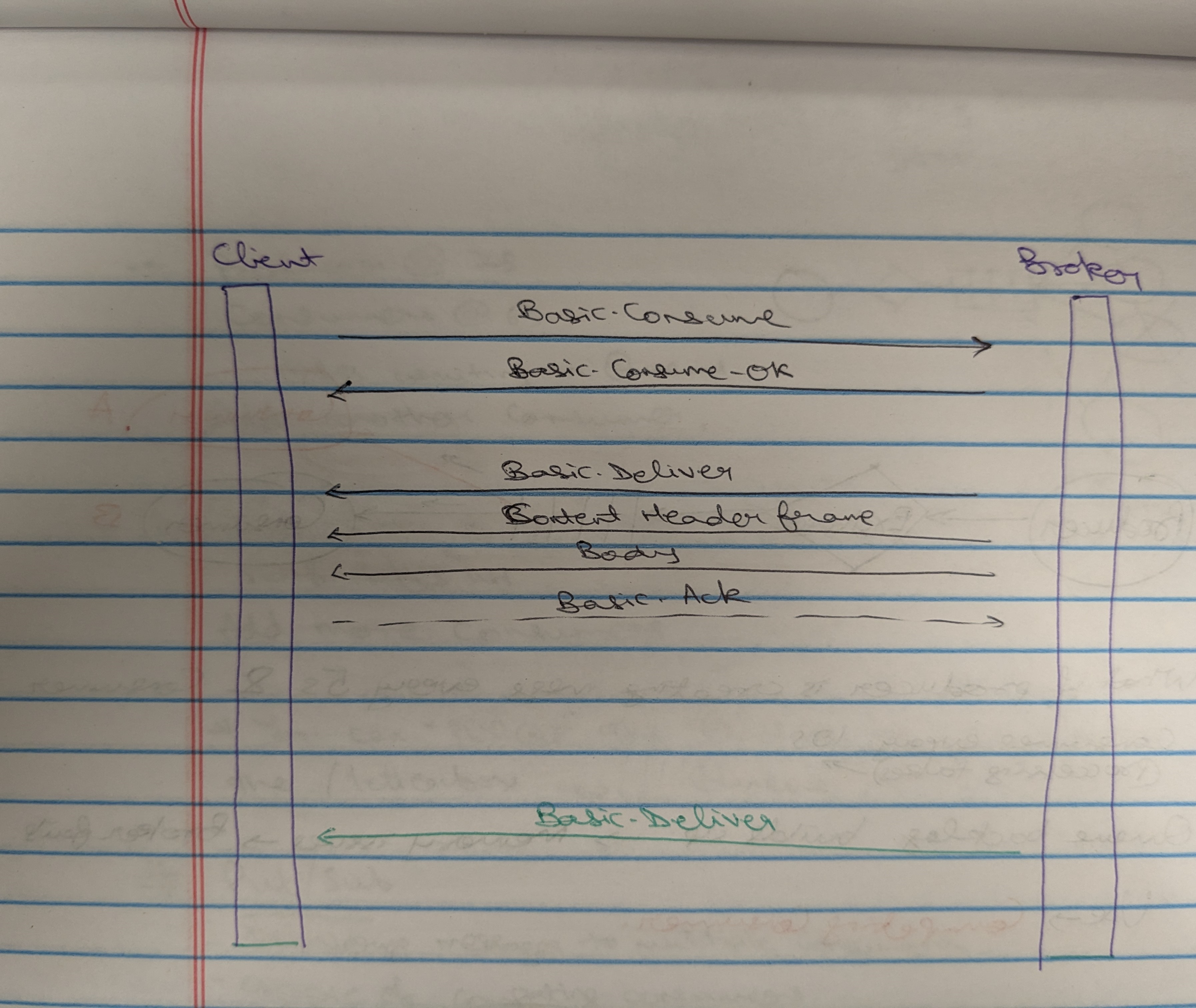

When sending/receiving messages through rabbitMQ, the first frame is always the "Method Frame" that corresponds to the sending/receiving message.

Opening a connection & Declaring a Queue:

Publishing & Consuming Messages:

- Installation using Chocolatey (Windows)

choco install rabbitmq- Pull and Run the RabbitMQ Docker Container:

docker run -d --hostname rmq --name rabbit-server -p 8080:15672 -p 5672:5672 rabbitmq:3-managementYou can access the RabbitMQ management UI in your web browser at http://localhost:8080/. Log in with the default credentials (username: guest, password: guest).

- A simple Producer-Consumer/Publisher-Subscriber model

Demonstrates a simple example of using the RabbitMQ message broker with Python, where you have a publisher that sends messages to a queue and a consumer that receives and processes those messages. RabbitMQ is a message broker that allows different parts of your application to communicate by sending and receiving messages.

Publisher Code: The publisher code is responsible for sending messages to a RabbitMQ queue. It begins by importing the 'pika' library, which is used for RabbitMQ communication. It establishes a connection to a RabbitMQ server running on the local machine or a specified hostname. A channel is created for communication with RabbitMQ, and a queue named 'letterbox' is declared. The publisher prepares a message, such as 'hello world,' and sends it to the 'letterbox' queue using the 'basic_publish' method. After successful publishing, it prints a confirmation message and closes the connection.

Consumer Code: The consumer code is designed to receive and process messages from the same RabbitMQ 'letterbox' queue that the publisher uses. Similar to the publisher, it imports the 'pika' library and establishes a connection to the RabbitMQ server. A channel is created and associated with the 'letterbox' queue, which is declared if it doesn't already exist. The consumer sets up a callback function called 'on_message_received' to handle incoming messages, in this case, printing the received message. It then starts consuming messages from the queue using 'channel.start_consuming()'. The program will stay active and responsive to incoming messages, invoking the 'on_message_received' function each time a new message arrives.

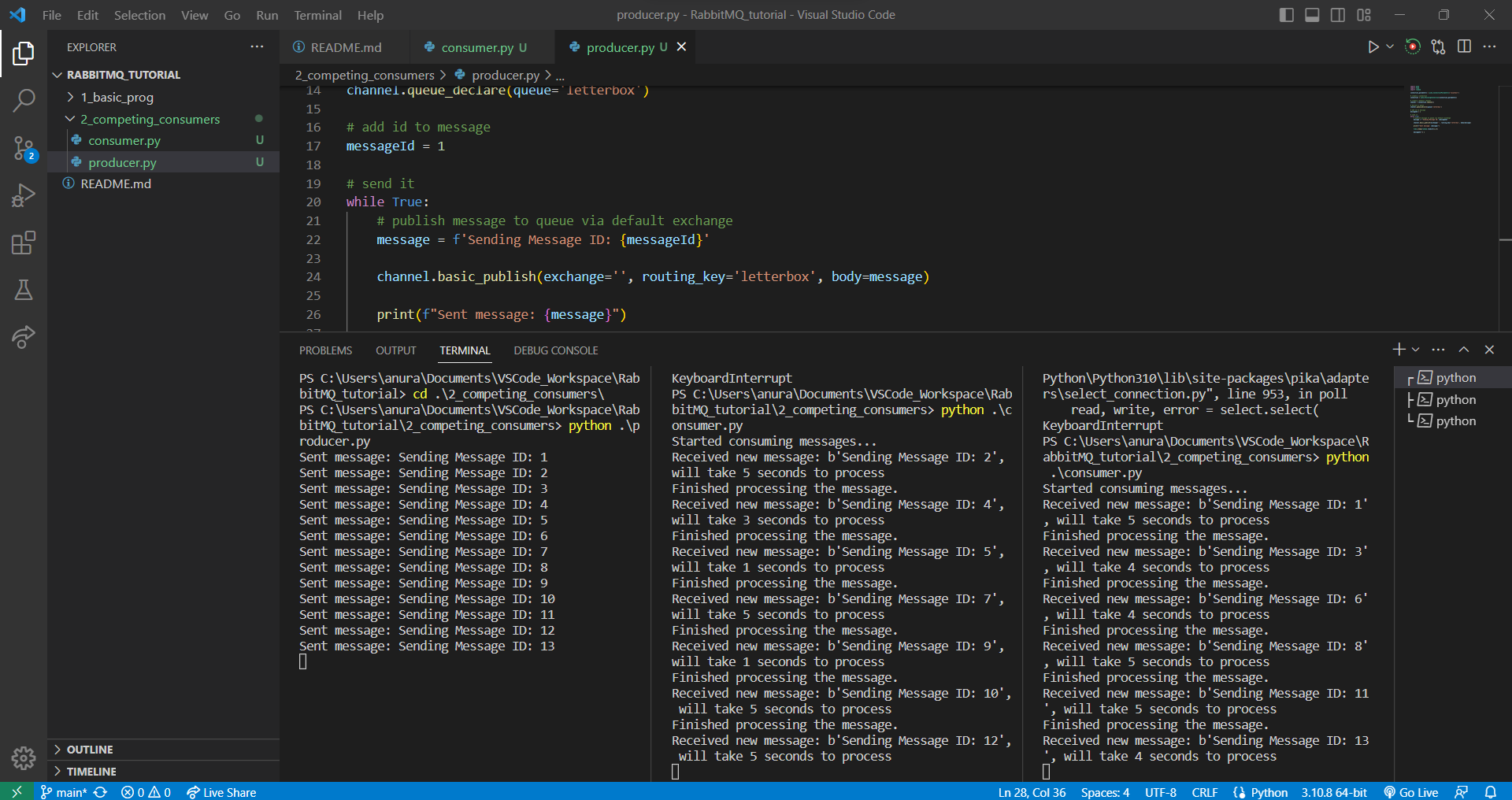

- Competing Consumers and a Producer - Work Queues

Simulating asynchronous message processing with a RabbitMQ consumer and a publisher.

The consumer simulates variable processing times for messages, while the publisher continuously sends messages to the queue. This example illustrates how RabbitMQ can be used to build distributed and resilient messaging systems, enabling components to work independently and handle varying workloads efficiently.

Problem:

What if producer is creating messages every 5 seconds and consumers consumes every 10 seconds. Consequentially, a queue backlog builds up, memory issues and eventually broker fails.

So, use the concept of competing consumers.

By default, RabbitMQ uses round-robin fashion to send messgaes to consumers. (A B A B A B ...)

Scenario:

Producer produces every 5 seconds.

Consumer A = 15 seconds to consume

Consumer B = 2 seconds to consume

Here, round-robin strategy fails! because Consumer B's consumption of messages will depend on the processing/consuming time taken by Consumer A.

Solution: We can set the prefetch value=1, so we tell the RabbitMQ to not give more than 1 message to a worker so Consumer B is not left idle. But, still messages build up in Queue.

Two Competing Consumers and One Producer:

- Publisher-Subscriber

Demonstration of a publish-subscribe messaging pattern using the RabbitMQ message broker. In this pattern, there is a producer that sends messages to an exchange, and there are two consumers that receive messages from the same exchange. The exchange acts as a broadcaster, distributing messages to all bound queues (consumers) without knowing about them individually.

- This is the opposite of the Competing Consumers strategy.

- This decouples the producer from consumer.

- We don't want to send messages directly to every service that's interested.

- Routing

-

Fanout exchanges deliver the message to all bound queues without any filtering or routing logic. This is a drawback when you need more fine-grained control over message routing based on message content or other criteria. For example, if you want to selectively route messages to different consumers based on their content, a fanout exchange might not be the best choice.

-

Fanout exchanges consume resources (CPU and memory) since they need to keep track of all the queues to which they need to broadcast messages. In situations with a large number of queues, this can lead to increased resource usage.

-

Because fanout exchanges send the same message to multiple queues, you might encounter message duplication issues if you have multiple consumers reading from different queues. Handling duplicate messages can be challenging.

Queues are bound to TOPIC exchanges with the routing key. This is a pattern matching process which is used to make decisions around routing messages. It does this by checking if a message’s Routing Key matches the desired pattern.

A Routing Key is made up of words separated by dots.

The Binding Key for Topic Exchanges is similar to a Routing Key, however there are two special characters, namely the asterisk * and hash #. These are wildcards, allowing us to create a binding in a smarter way. An asterisk * matches any single word and a hash # matches zero or more words.

Routing using the Direct Exchange:

Unlike a fanout exchange, which broadcasts messages to all bound queues, a direct exchange routes messages to specific queues based on a routing key. This routing key is specified by the sender when publishing a message, and queues are bound to the direct exchange with routing keys that indicate which messages they are interested in receiving.

Direct exchanges enable selective message routing based on routing keys. Messages are only delivered to queues that have explicitly expressed interest in messages with matching routing keys.

Routing using the Topic Exchange:

It is designed to provide more flexible and powerful message routing compared to direct and fanout exchanges. A topic exchange uses a routing key, like a direct exchange, but it also introduces wildcard characters to allow for more advanced pattern-based routing.

Consumers can subscribe to specific types of messages by using routing key patterns that match their interests, allowing for selective message consumption.

* (asterisk) matches a single word in the routing key. For example, a routing key of "stock.usd" would match a pattern of "stock.*".

For example, if you have a routing key of "stock.usd" and a binding with a pattern of "stock.*," the message will match because the asterisk matches "usd," a single word.

However, if you have a routing key like "stock.usd.market" and a binding with a pattern of "stock.*," it will not match because the asterisk only matches a single word. In this case, you would need to use the hash (#) to match one or more words.

# (hash) matches one or more words in the routing key. For example, a routing key of "stock.usd.market" would match a pattern of "stock.#".

For example, if you have a routing key like "stock.usd.market" and a binding with a pattern of "stock.#," the message will match because the hash matches "usd.market," which is one or more words.

The hash is more flexible than the asterisk because it can match multiple words, allowing for more extensive pattern-based routing.

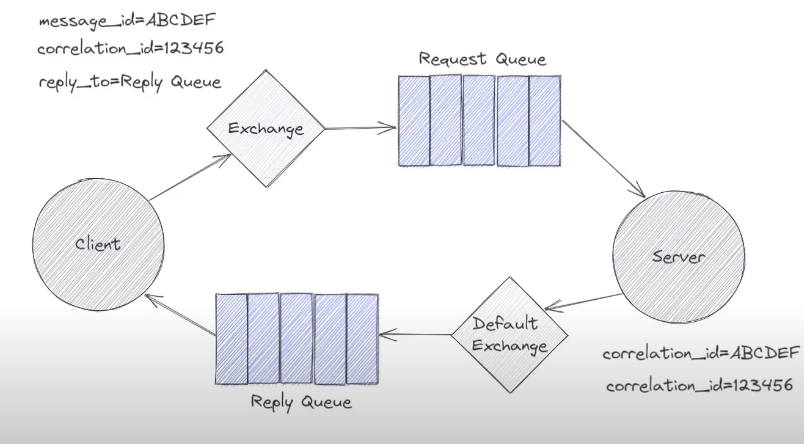

- Request-Response Pattern - Remote Procedure Call or RPC

The request-response pattern in RabbitMQ, often referred to as RPC (Remote Procedure Call), is a communication pattern where one application (the client) sends a request to another application (the server) and waits for a response.

Applications:

- Web services: Clients make RPCs to remote web servers to fetch data or perform actions (e.g., RESTful APIs).

- Database systems: Database clients use RPC to execute queries and transactions on a remote database server.

How RPC Works:

The client sends a request message to the 'request-queue' and waits for a response on its unique reply queue.

The server, listening on the 'request-queue', processes incoming requests and sends a reply to the reply queue specified in the request message's reply_to property.

When the server sends the reply, it includes the same correlation_id that was in the request, allowing the client to match the response to the correct request.

The client, using the consumer on its reply queue, receives and processes the response message, and the result is printed.

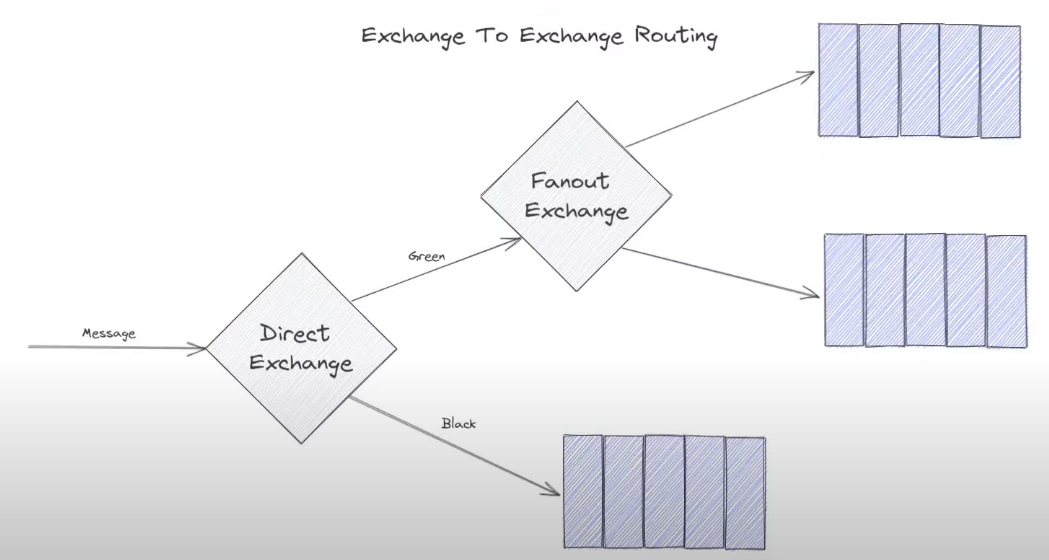

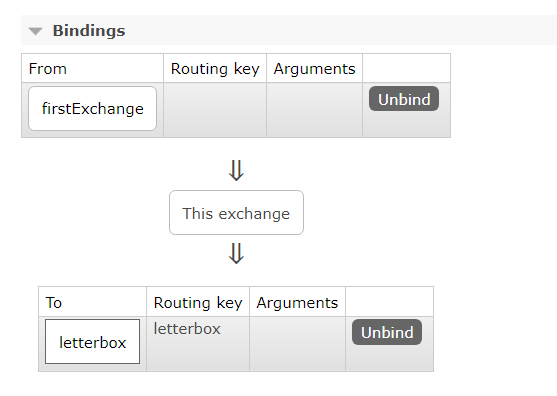

- Exchange To Exchange Routing

Exchanges can not only be bound to Queues, but they can also be bound to other Exchanges. Exchange-to-Exchange (E2E) routing, also known as Exchange Federation, is a powerful routing pattern in RabbitMQ that allows messages to be forwarded or routed between exchanges. This pattern is useful when you have multiple exchanges in your RabbitMQ setup, and you want to define complex routing logic by forwarding messages from one exchange to another based on certain criteria.

Example:

Suppose you have three exchanges: exchangeA, exchangeB, and exchangeC. You can set up E2E routing as follows:

Bind exchangeA to exchangeB with a specific routing key. Bind exchangeA to exchangeC with a different routing key. When messages are published to exchangeA with routing keys matching the bindings, they will be routed to both exchangeB and exchangeC. This allows you to split and forward messages based on specific criteria, and each destination exchange (exchangeB and exchangeC) can have its own set of queues and consumers for further processing.

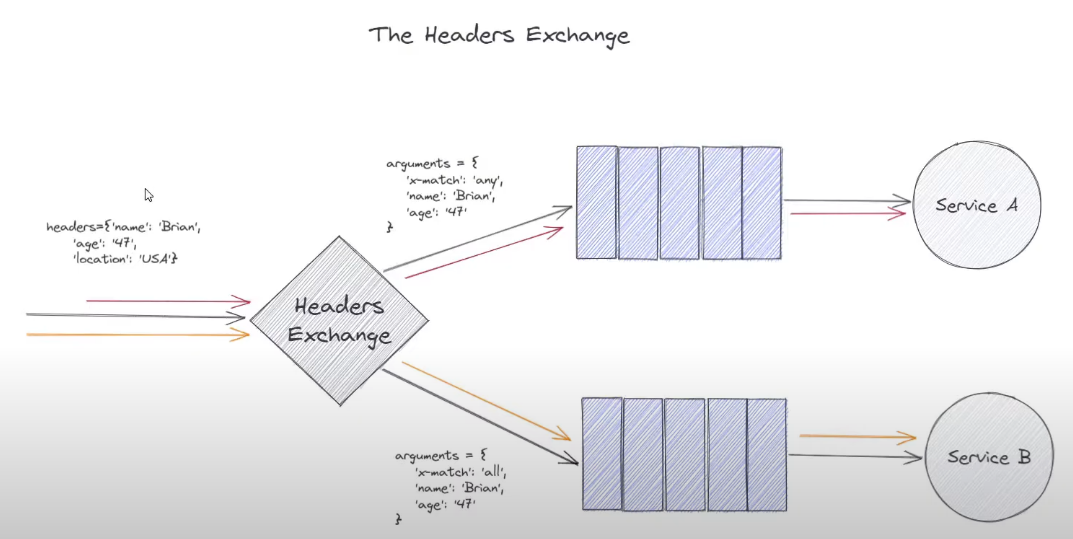

- The Headers Exchange

Headers Exchange is a type of exchange that uses message header attributes, rather than routing keys, for message routing. Messages are routed to queues based on header attribute matching criteria defined in bindings between the exchange and queues. This exchange type is particularly useful when you need to route messages based on header attribute values, and it provides a high degree of flexibility in message routing.

x-match:any

If you declare a binding with x-match:any, it means that if any of the header attributes in the binding matches any of the header attributes in the message, the message will be routed to the associated queue.

For example, if you have a binding with x-match:any and criteria {header1: 'value1', header2: 'value2'}, then a message with either header1: 'value1' or header2: 'value2' (or both) will match and be routed to the queue.

x-match:all

If you declare a binding with x-match:all, it means that all of the header attributes in the binding must match their corresponding header attributes in the message for the message to be routed to the associated queue.

For example, if you have a binding with x-match:all and criteria {header1: 'value1', header2: 'value2'}, then a message must have both header1: 'value1' and header2: 'value2' to match and be routed.

Note: Make sure to unbind any arguments from the queue if you will be sending all arguments in the header next.

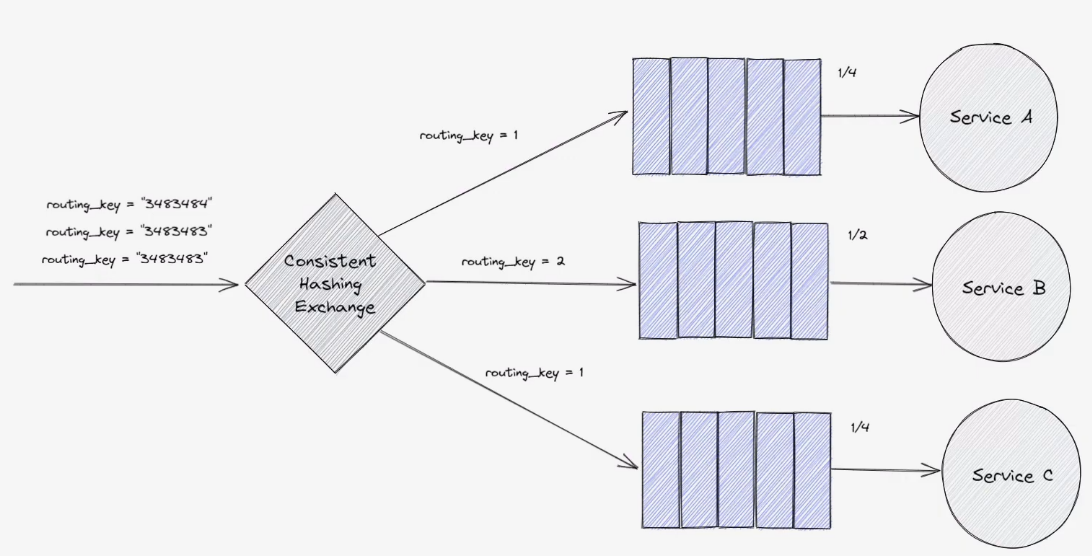

- The Consistent Hashing Exchange

RabbitMQ has 4 default exchange types:

- Direct

- FanOut

- Topic

- Headers

Consistent hashing is a technique used in distributed systems to distribute data or workload across multiple nodes in a way that minimizes the reshuffling of data when nodes are added or removed from the system. It's commonly used in scenarios like distributed caching, distributed databases, and load balancing.

In consistent hashing, a hash function is used to map data or requests to a range of values (often a circle or ring) and then map each node in the system to a position on the same circle. Data or requests are assigned to the nearest node in a clockwise direction.

While RabbitMQ doesn't have a built-in "Consistent Hashing Exchange," you can implement consistent hashing as part of your application's logic when using RabbitMQ for specific use cases. Instead, it's a concept often associated with distributed systems and load balancing, and it can be implemented using custom logic and plugins in RabbitMQ.

In this case, I've decided to give service #2 twice as much hashing space as the other two services. This means that service #2 will be responsible for handling a larger portion of the hashed values in the ring compared to the other two services.

Service #A and Service #C: Each of these services is assigned an equal portion of the hash space on the ring, which is typically 1/3 of the total space since you have three services.

Service #B: This service is assigned a larger portion of the hash space, specifically 2/3 of the total space since it has twice the hashing space as the other two services.

If you add another service to your system while using weighted consistent hashing, you'll need to update the hashing strategy to accommodate the new service's allocation of the hash space. This computation should take into account the desired weight of the new service and any changes to the weights of existing services.

- Go to Docker Desktop

- Run the following commands:

# ls

bin boot devetc home liblib32 lib64 libx32 media mnt opt pluginsproc root run sbin srv sys tmp usr var

# cd sbin

# rabbitmq-plugins enable rabbitmq_consistent_hash_exchange

Enabling plugins on node rabbit@rmq:

rabbitmq_consistent_hash_exchange

The following plugins have been configured:

rabbitmq_consistent_hash_exchange

rabbitmq_management

rabbitmq_management_agent

rabbitmq_prometheus

rabbitmq_web_dispatch

Applying plugin configuration to rabbit@rmq...

The following plugins have been enabled:

rabbitmq_consistent_hash_exchange

started 1 plugins.

# ContentType - application/json, application/pdf

- It specifies the MIME type of the message content. This helps consumers understand how to interpret the message payload.

ContentEncoding - gzip, compress, deflate

- It specifies the encoding of the message content if it's not in its original form. This is typically used when the message body is compressed.

Timestamp - 1640030010

- It specifies when the message was created. This can be helpful for tracking and auditing purposes.

DeliveryMode - 0,1

- it specifies whether a message should be persisted to disk or not. It can have one of two values:

0 (Non-Persistent): If you set the deliveryMode to 1, it indicates that the message should be treated as non-persistent. In this case, RabbitMQ will keep the message in memory and will not write it to disk. Non-persistent messages are faster to publish and consume but are not guaranteed to survive server restarts or crashes. They may be lost if RabbitMQ restarts or fails.

1 (Persistent): When you set the deliveryMode to 2, it indicates that the message should be treated as persistent. RabbitMQ will make sure that the message is written to disk before acknowledging receipt. Persistent messages are slower to publish and consume because of the disk I/O but are guaranteed to survive server restarts or crashes. They are a good choice for important data that must not be lost.

Expiration - 90061

- allows you to specify a time limit for how long a message should be considered valid and retained by the RabbitMQ broker. Once a message's expiration time has passed, RabbitMQ will discard the message, and it will not be delivered to consumers, even if it hasn't been consumed yet.

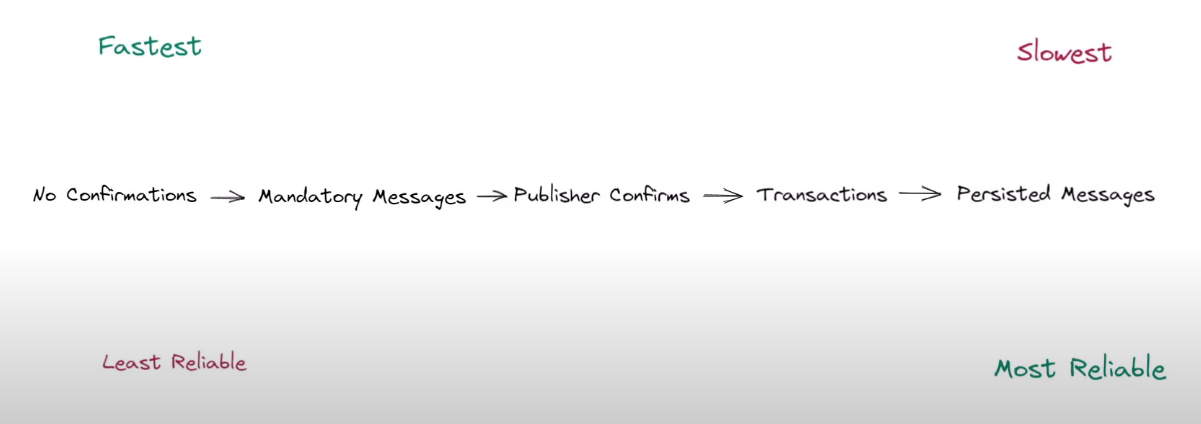

Speed: If you prioritize speed, you can publish messages without confirmations, with non-persistent delivery (deliveryMode 0), and without using transactions. This allows for quick message publication but sacrifices some level of resiliency.

Resiliency: To prioritize resiliency, you can enable features like publisher confirms, use mandatory messages to prevent message loss, use transactions to ensure atomicity, and publish messages with persistence (deliveryMode 1). These features ensure that messages are reliably delivered and persisted, but they come at the cost of slower publishing due to acknowledgment and disk I/O operations.

No Confirmations: When you publish a message without using publisher confirms, the publishing process is relatively fast, as there's no need for acknowledgments from the broker. However, this approach lacks resiliency because you have no assurance that the message was successfully received and stored by RabbitMQ. If a network issue or broker problem occurs, messages might be lost.

Mandatory Messages: Mandatory messages are published with the expectation that they must be routed to at least one queue. If no queue can accept the message, it is returned to the publisher. This can improve resiliency by ensuring that messages are not silently dropped, but it may slow down publishing slightly due to the need for routing checks.

Publisher Confirms: Publisher confirms are a resiliency feature that allows the publisher to receive acknowledgments from RabbitMQ once a message has been successfully enqueued by the broker. While this improves resiliency by providing confirmation of message receipt, it adds a level of latency to the publishing process because the publisher must wait for acknowledgments.

Transactions: Transactions provide a strong guarantee of message durability and consistency. With transactions, messages are published within a transaction context, and they are only considered published if the transaction is committed successfully. This ensures that messages are either fully delivered or not delivered at all. However, transactions are relatively slow compared to non-transactional publishing because they involve additional processing and synchronization.

Persisted Messages: Persisted messages are those with a deliveryMode of 1, which means they are stored on disk by RabbitMQ. This is a crucial feature for resiliency because it guarantees that messages will survive broker restarts and crashes. However, writing messages to disk incurs I/O overhead, making publishing slower compared to non-persistent messages (deliveryMode 0).

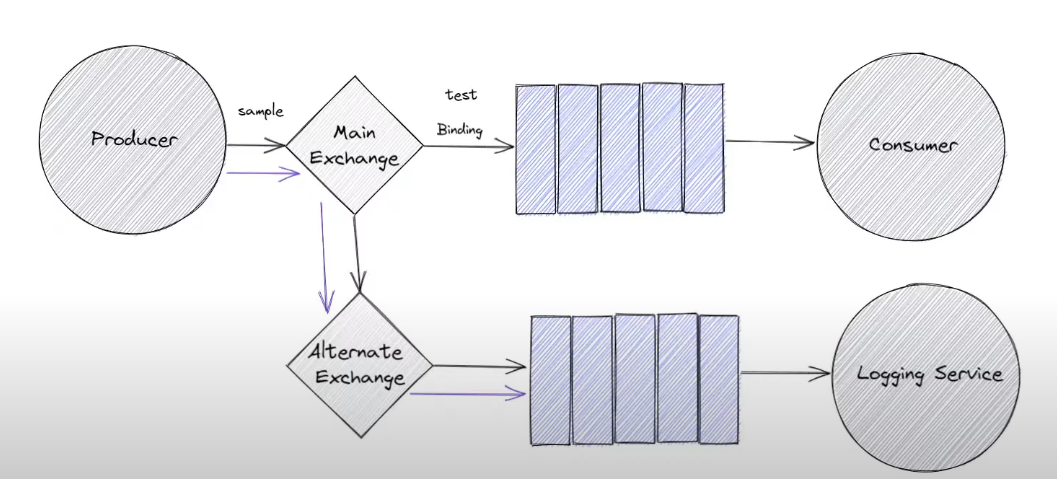

An alternate exchange, often referred to as an "AE," is a feature in RabbitMQ that allows you to define an exchange to which messages are sent if they cannot be routed to any queue. In other words, when a message arrives at an exchange, and there are no queues bound to that exchange with a routing key that matches the message, RabbitMQ will route the message to the alternate exchange, if one is specified.

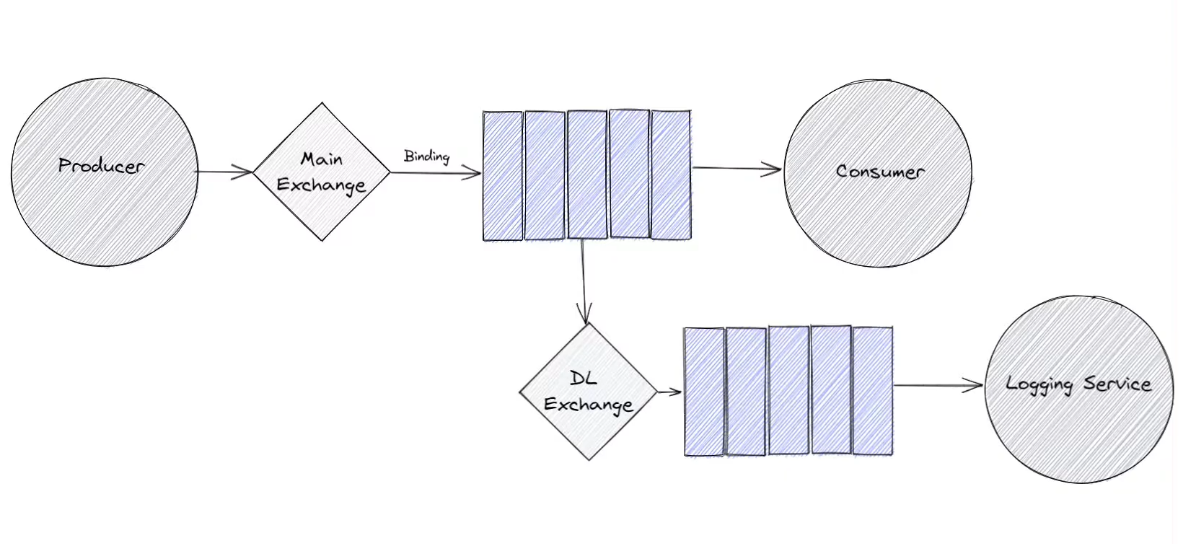

A Dead Letter Exchange (DLX) is a feature in RabbitMQ that allows you to specify an exchange where messages are sent when they cannot be routed to any queue or when they are rejected by a queue. DLX is commonly used to handle messages that, for various reasons, cannot be processed in the normal flow of your messaging system.

DLX is primarily for error handling, retries, and capturing problematic messages in dedicated dead-letter queues. AE, on the other hand, is more versatile in routing undeliverable messages to different destinations based on routing rules, making it suitable for various scenarios beyond just error handling.

When auto_ack is set to True, it means that RabbitMQ will automatically acknowledge (ack) the message as soon as it is delivered to the consumer. The consumer doesn't need to manually acknowledge the message. This can be convenient but may not be suitable for scenarios where you need more control over acknowledgment (e.g., after successful processing).

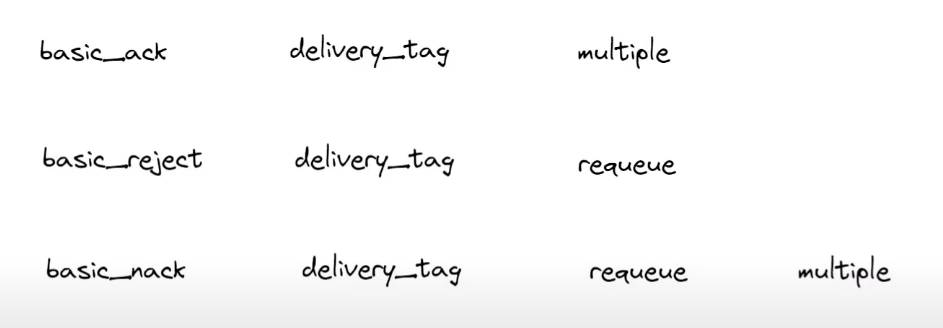

basic_ack is a method used by a consumer to acknowledge a message explicitly. It's used when auto_ack is set to False, and the consumer wants to confirm that it has successfully processed and handled the message. By acknowledging a message, the consumer informs RabbitMQ that it can remove the message from the queue.

basic_reject is a method used by a consumer to reject and return a message to the queue. It's often used when a message cannot be processed successfully and should be placed back in the queue for reprocessing or for handling by another consumer. basic_reject allows specifying whether the message should be requeued or not.

basic_nack is similar to basic_reject but provides more advanced features. It allows rejecting multiple messages at once and specifying whether to requeue them. basic_nack is useful when you need to reject multiple messages in a batch or have more fine-grained control over requeuing behavior.

multiple is a parameter used with basic_ack and basic_nack methods. When multiple is set to True, it means that not just one but multiple messages up to and including the specified delivery_tag will be acknowledged or rejected. This is useful when you want to acknowledge or reject multiple messages in a batch.

delivery_tag is a unique identifier assigned by RabbitMQ to each message delivered to a consumer. It's used when acknowledging or rejecting a message to specify which message is being acted upon. When acknowledging or rejecting a message, you reference it by its delivery_tag

requeue is a parameter used with basic_reject and basic_nack methods. When requeue is set to True, it means that the rejected message(s) should be placed back in the queue for reprocessing. If requeue is set to False, the message(s) will be discarded.

- auto delete [delete queue when no longer required] The "auto delete" attribute is a property that can be assigned to an exchange or a queue. It determines whether the exchange or queue should be automatically deleted by RabbitMQ when it is no longer in use.

When a queue is marked as "auto-delete," RabbitMQ will automatically remove the queue from the server when it is no longer in use. This typically means that all consumers have canceled their subscriptions to the queue, and there are no more messages left in the queue.

queue_name = 'auto_delete_queue'

channel.queue_declare(queue=queue_name, auto_delete=True)- auto expire [delete queue after period of unised time] auto expire for queues is a feature that allows you to specify a time limit (in milliseconds) for how long a queue should exist. Once this time limit is reached, RabbitMQ will automatically remove the queue from the server.

Auto-expire is often used for temporary queues created for short-term purposes, such as request/response patterns, caching, or short-lived processing. It ensures that queues are automatically cleaned up when they are no longer needed.

queue_args = {"x-expires": 3600000} # 3600000 milliseconds = 1 hour

channel.queue_declare(queue="my_queue", arguments=queue_args)- auto expire msg [expire messages if they sit on a queue for a long time] auto expire msg are messages that have a time-to-live (TTL) set. Once a message sits in a queue for longer than its TTL, RabbitMQ will automatically remove it from the queue.

This feature is handy for scenarios where you want to ensure that messages do not linger in a queue indefinitely. For example, in a chat application, you might set a TTL for messages to delete old messages after a certain time.

- max length queue [set max number of messages allowed on queue] auto expire msg : a queue with a specified maximum length, meaning it can only hold a certain number of messages at a time. When the queue reaches its maximum length, new messages will be dropped or handled according to your defined policy (e.g., reject, publish to an alternate queue, etc.).

Max-length queues are useful when you want to control the size of your queues to prevent them from growing too large and consuming excessive memory. For example, in a job processing system, you may want to limit the queue to hold only a certain number of pending jobs.

- exclusive [only allows one consumer at a time] An exclusive queue or consumer is one that is accessible only by the connection that declared it. No other connections can access or use the same queue. Once the connection that declared the exclusive queue is closed, the queue is deleted automatically.

Exclusive queues are often used when you want to ensure that only one consumer can process messages from a specific queue at a time. It's useful for scenarios like workload balancing or task assignment, where you want to avoid parallel processing.

- durable [sets the queue to survive server restarts] A durable queue is one that survives server restarts. When a queue is marked as durable, RabbitMQ will make sure that the queue and its messages are persisted to disk, ensuring that they can be recovered even if the server restarts.

Durable queues are crucial when you want to ensure that important messages are not lost in the event of a server crash or restart. For example, in a message broker used for critical financial transactions, you would want to make sure that no messages are lost due to server failures.

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLalrWAGybpB-UHbRDhFsBgXJM1g6T4IvO - jumpstartCS tutorial on RabbitMQ