This is a toy project of mine, with the goal of making a compiler for C, written in C, which is able to compile itself.

- Complete support for C89, in addition to some features from later standards.

- Target x86_64 assembly GNU syntax (-S), binary ELF object files (-c), or pure preprocessing (-E).

- Rich intermediate representation, building a control flow graph (CFG) with basic blocks of three-address code for each function definition. This is the target for basic dataflow analysis and optimization.

Clone and build from source, and the binary will be placed in bin/lacc.

Default include paths assume GNU standard library headers being available, at /usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu.

To change to some other libc, for example musl, edit src/main.c.

git clone https://github.com/larmel/lacc.git

cd lacc

make

Certain standard library headers, such as stddef.h and stdarg.h, contain definitions that are inherently compiler specific, and are provided specifically

for lacc under include/stdlib/.

The compiler is looking for these files at a default include path configurable by defining LACC_STDLIB_PATH, which by default points to the local source tree.

Install copies the standard headers to /usr/local/lib/lacc/include, and produces an optimized binary with this as the default include path.

make install

The binary is placed in /usr/local/bin, which enables running lacc directly

from terminal.

Execute make uninstall to remove all the files that were copied.

Command line interface is kept similar to GCC and other compilers, using mostly a subset of the same flags and options. A custom argument parser is used, and the definition of each option can be found in src/main.c.

-E Output preprocessed.

-S Output GNU style textual x86_64 assembly.

-c Output x86_64 ELF object file.

-o Specify output file name. If not specified, default to stdout.

-std= Specify C standard, valid options are c89, c99, and c11.

-I Add directory to search for included files.

-w Disable warnings.

-O[1-3] Enable optimization.

-D X[=] Define macro, optionally with a value. For example -DNDEBUG, or

-D 'FOO(a)=a*2+1'.

-v Output verbose diagnostic information. This will dump a lot of

internal state during compilation, and can be useful for debugging.

--help Print help text.

Input is by default read from stdin, unless specified as a separate unnamed argument.

As an example invocation, here is compiling test/fact.c to object code, and then using GCC linker to produce the final executable.

bin/lacc -c test/fact.c -o fact.o

gcc fact.o -o fact

The program is part of the test suite, calculating 5! using recursion, and exiting with the answer.

Running ./fact followed by echo $? should print 120.

The compiler is written in C89, with no external dependencies other than the C standard library. There is around 13k lines of code total.

The implementation is organized into four main parts; preprocessor, parser, optimizer, and backend, each in their own directory under src/.

In general, each module (a .c file typically paired with an .h file defining the public interface) depend mostly on headers in their own subtree.

Declarations that are shared on a global level reside in include/lacc/.

This is where you will find the core data structures, and interfaces between preprocessing, parsing, and code generation.

Preprocessing includes reading files, tokenization, macro expansion, and directive handling.

The interface to the preprocessor is peek(0), peekn(1), consume(1), and next(0), which looks at a stream of preprocessed struct token objects.

These are defined in include/lacc/token.h.

Input processing is done completely lazily, driven by the parser calling these four functions to consume more input. A buffer of preprocessed tokens is kept for lookahead, and filled on demand when peeking ahead.

Code is modeled as control flow graph of basic blocks, each holding a sequence of three-address code statements.

Each external variable or function definition is represented by a struct definition object, defining a single struct symbol and a CFG holding the code.

The data structures backing the intermediate representation can be found in include/lacc/ir.h.

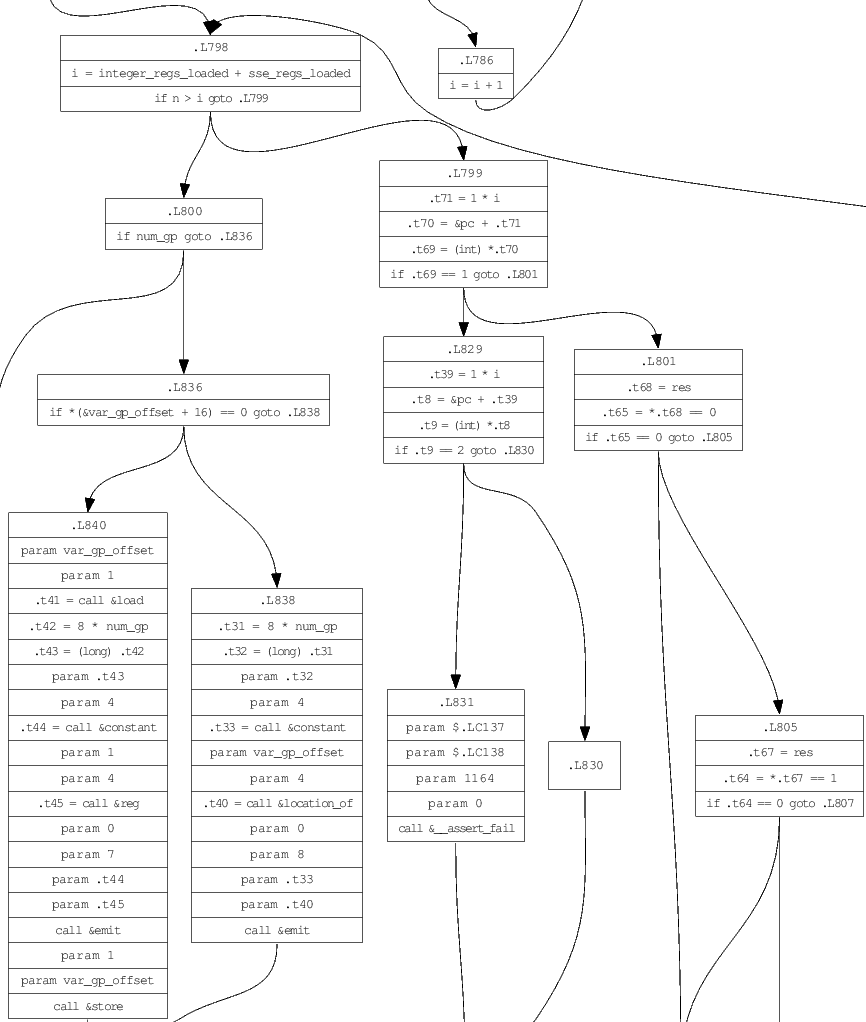

Visualizing the intermediate representation is a separate output target. If neither -S, -c, nor -E are specified, a dot formatted text file is produced.

bin/lacc -I include src/backend/compile.c -o compile.dot

dot -Tps compile.dot -o compile.ps

Below is an example from a function found in src/backend/compile.c, showing a slice of the complete graph. The full output can be generated as a PostScript file by running the commands shown.

Each basic block in the graph has a list of statements, most commonly IR_ASSIGN, which assigns an expression (struct expression) to a variable (struct var).

Expressions also contain variable operands, which can encode memory locations, addresses and dereferenced pointers at a high level.

DIRECToperands refer to memory at*(&symbol + offset), where symbol is a variable or temporary at a specific location in memory (for example stack).ADDRESSoperands represent exactly the address of aDIRECToperand, namely(&symbol + offset).DEREFoperands refer to memory pointed to by a symbol (which must be of pointer type). The expression is*(symbol + offset), which requires two load operations to map to assembly. OnlyDEREFandDIRECTvariables can be target for assignment, or l-value.IMMEDIATEoperands hold a constant number, or string. Evaluation of immediate operands do constant folding automatically.

The parser is hand coded recursive descent, with main parts split into src/parser/declaration.c, src/parser/initializer.c, src/parser/expression.c, and src/parser/statement.c. The current function control flow graph, and the current active basic block in that graph, are passed as arguments to each production. The graph is gradually constructed as new three-address code instructions are added to the current block.

The following example shows the parsing rule for bitwise or expressions, which

adds a new IR_OP_OR operation to the current block.

Logic in eval_expr will ensure that the operands value and block->expr are valid, terminating in case of an error.

static struct block *inclusive_or_expression(

struct definition *def,

struct block *block)

{

struct var value;

block = exclusive_or_expression(def, block);

while (peek().token == '|') {

consume('|');

value = eval(def, block, block->expr);

block = exclusive_or_expression(def, block);

block->expr = eval_expr(def, block, IR_OP_OR, value,

eval(def, block, block->expr));

}

return block;

}

The latest evaluation result is always stored in block->expr.

Branching is done by instantiating new basic blocks and maintaining pointers.

Each basic block has a true and false branch pointer to other blocks, which is how branches and gotos are modeled.

Note that at no point is there any syntax tree structure being built.

It exists only implicitly in the recursion.

The main motivation for building a control flow graph is to be able to do dataflow analysis and optimization. The current capabilities here are still limited, but it can easily be extended with additional and more advanced analysis and optimization passes.

Liveness analysis is used to figure out, at every statement, which symbols may later be read. The dataflow algorithm is implemented using bit masks for representing symbols, numbering them 1-63. As a consequence, optimization only works on functions with less than 64 variables. The algorithm also has to be very conservative, as there is no pointer alias analysis (yet).

Using the liveness information, a transformation pass doing dead store elimination can remove IR_ASSIGN nodes which provably do nothing, reducing the size of the generated code.

There are three backend targets: textual assembly code, ELF object files, and

dot for the intermediate representation.

Each struct definition object yielded from the parser is passed to the src/backend/compile.c module.

Here we do a mapping from intermediate control flow graph representation down to a lower level IR, reducing the code to something that directly represents x86_64 instructions.

The definition for this can be found in src/backend/x86_64/instr.h.

Depending on function pointers set up on program start, the instructions are sent to either the ELF backend, or text assembly. The code to output text assembly is therefore very simple, more or less just a mapping between the low level IR instructions and their GNU syntax assembly code. See src/backend/x86_64/assemble.c.

Dot output is a separate pipeline that does not need low level IR to be generated. The compile module will simply forward the CFG to src/backend/graphviz/dot.c.

Testing is done by comparing the runtime output of programs compiled with lacc

and GCC.

A collection of small standalone programs used for validation can be found under the test/ directory.

Tests are executed using check.sh, which will validate preprocessing, assembly, and ELF outputs.

Executing all tests in the test suite against bin/lacc is done with the following make target.

make test

The default binary is produced by GCC, giving bin/lacc.

Self-hosting is achieved by using bin/lacc to build bin/bootstrap, which in turn is used to build bin/selfhost.

Make targets for running the test suite against the bootstrap and selfhost binaries are available.

The compiler is ''good'' when all tests pass on the selfhost binary.

This should always be green, on every commit.

make test-selfhost

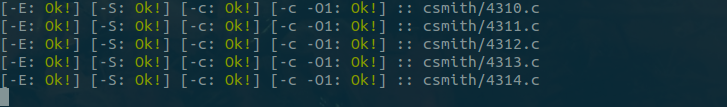

It is hard to come up with a good test suite covering all possible cases. In order to weed out bugs, we can use csmith to generate random programs that are suitable for validation.

make csmith-test

To use this, you will need to install csmith, and update CSMITH_HOME_PATH in

the Makefile. The make target will run csmith.sh, which generates

an infinite sequence of random programs until something fails the test harness.

It will typically run thousands of tests without failure.

The programs generated by Csmith contain a set of global variables, and functions making mutations on these. At the end, a checksum of the complete state of all variables is output. This checksum can then be compared against different compilers to find discreptancies, or bugs. See doc/random.c for an example program generated by Csmith, which is also compiled correctly by lacc.

When a bug is found, we can use creduce to make a minimal repro. This then will end up as a new test case in the normal test suite.

Some effort has been put into making the compiler itself fast (although the generated code is still very much unoptimized). Serving as both a performance benchmark and correctness test, we use the sqlite database engine. The source code is distributed as a single ~7 MB large C file spanning more than 200 K lines (including comments and whitespace), which is perfect for stress testing the compiler.

The following experiments were run on a laptop with an i5-7300U CPU, compiling version 3.20.1 of sqlite3. Measurements are made from compiling to object code (-c).

It takes less than 200 ms to compile the file with lacc, but rather than time we look at a more accurate sampling of CPU cycles and instructions executed.

Hardware performance counter data is collected with perf stat, and memory allocations with valgrind --trace-children=yes.

In valgrind, we are only counting contributions from the compiler itself (cc1 executable) while running GCC.

Results for clang is missing because it for some reason crashes under valgrind.

Numbers for lacc is from an optimized build produced by clang (-O3), compiled from a single file generated by amalgamation.py.

| Compiler | Cycles | Instructions | Allocations | Bytes allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lacc | 564,093,304 | 748,670,355 | 62,305 | 30,986,825 |

| tcc (0.9.27) | 231,212,025 | 389,553,813 | 2,795 | 22,969,302 |

| gcc (6.3.0) | 9,128,950,153 | 14,009,317,914 | 1,508,037 | 715,297,766 |

| clang (4.0.0) | 4,037,958,570 | 5,538,918,744 | - | - |

There is yet work to be done to get closer to TCC, which is probably one of the fastest C compilers available. Still, we are within reasonable distance from TCC performance, and an order of magnitude better than GCC.

We can compare the relative quality of code generated from lacc and GCC by looking at the number of dynamic instructions executed by the selfhost binary versus a binary built by GCC. In both cases we do not enable any optimizations, so this is a measure of code generated with -O0.

| Compiler | Cycles | Instructions |

|---|---|---|

| lacc | 1,039,023,504 | 1,568,160,799 |

| lacc (selfhost) | 1,545,791,224 | 2,279,713,970 |

Around 50 % more instructions executed by the selfhost binary, showing that lacc generates more naive code than GCC. Improving the backend with more efficient instruction selection is a priority, so these numbers should get closer in the future.

These are some useful resources for building a C compiler targeting x86_64.

- The C Programming Language, Second Edition. Brian W. Kernighan, Dennis M. Ritchie.

- System V Application Binary Interface.

- Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manuals, specifically the instruction set reference.